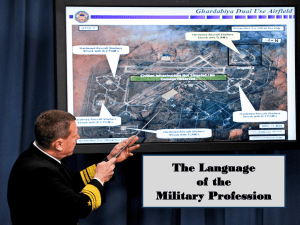

Major Combat Operations JOC

advertisement