The Psychiatric Perspectives of Epilepsy

advertisement

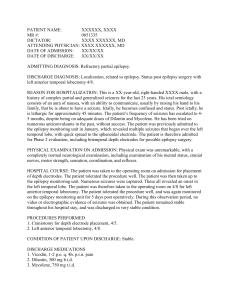

Texte trouvé par l’archive de documents concernant le domaine médical, Highwire Press de la Stanford University. Article paru dans la revue Psychosomatics, Official Journal of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Psychosomatics 41:31-38, February 2000 © 2000 The Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Special Article The Psychiatric Perspectives of Epilepsy Joseph M. Schwartz, M.D., and Laura Marsh, M.D. Received August 24, 1999; accepted September 16, 1999. From the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. Address reprint requests to Dr. Schwartz, Meyer 121, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD 21287-7144. ABSTRACT Psychiatric conditions occur frequently in epilepsy, and their manifestations are diverse. Evaluation and management require knowledge of disease processes relevant to epilepsy and to psychiatry, as well as the role of other factors that affect the expression of psychiatric illnesses: behaviors, temperament, cognition, and life events. This article describes a comprehensive approach for addressing psychiatric issues in epilepsy patients. Key Words: Neuropsychiatric Disorders • Epilepsy INTRODUCTION William Osler once said of syphilis, "I often tell my students that it is the only disease which they require to study thoroughly. Know syphilis in all its manifestations and reactions, and all things clinical will be added unto you."1 For psychiatry, epilepsy may play a similar role because it could be the etiology for almost any symptom. Therefore, a review of all the psychiatric aspects of epilepsy becomes a review of the practice of psychiatry. Because many excellent reviews of the psychiatric aspects of epilepsy are available,2–6 we present here a method for systematically addressing psychiatric issues in epilepsy. THE PERSPECTIVES OF PSYCHIATRY APPLIED TO EPILEPSY The method we present proposes looking at psychiatric issues in every patient with epilepsy through four perspectives, or lenses, each with particular assumptions and implications for treatment.7 They are the perspectives of 1) diseases; 2) dimensions; 3) behaviors; and 4) life stories. The purpose of each perspective is to provide a framework for evaluating patient symptoms and related phenomenology (description), determining causes of psychiatric disturbance (explanation), and formulating treatment programs. The disease perspective assumes that the cause of a psychiatric symptom is a "broken part;" that is, biological dysfunction involving the nervous system. In other instances, patients are not troubled because of the disease they have but because of what they are doing; this is the behavior perspective. The dimension perspective is based on the recognition that human traits vary from individual to individual along a continuum. Like height and blood pressure for physical medicine, there are psychiatric dimensions. Two of the most important are temperament (personality) and intelligence. Understanding where an individual lies along these dimensions provides information about how a given patient might be prone to developing psychopathology under various life circumstances. Individuals also experience problems because of what they encounter in life and the meanings they attribute to these life events. These meaningful connections form the basis of the life-story perspective. Because there are complex interactions between psychiatric phenomena and epilepsy, evaluating a patient with the four perspectives in mind guards against the possibility of neglecting some important aspect of a patient's condition. The symptom of anxiety, common in epilepsy, can be used as an example of the application of the four perspectives. The differential diagnosis will include presumed disease states (such as panic disorder and major depression), dimensional personality vulnerabilities (anxious temperament), behavioral issues (the embellishment of seizure symptoms or anxiety in order to attract medical attention or obtain medications), and life-story formulations (apprehension about one's future in the context of recurrent seizures). The treatment goals for each of the four perspectives vary, although the different types of treatments are often undertaken contemporaneously. In the disease perspective, the treatment goal is to fix, prevent, or compensate for the broken part. For problematic behaviors, the usual goal is to stop them. The goal for managing dimensional vulnerabilities is to educate and guide patients so that they can avoid or better cope with situations that make them susceptible to psychiatric dysfunction. In the life-story perspective, therapy helps assign new meanings to life events, thereby minimizing distress and maximizing personal efficiency. Consideration of each of the four perspectives is needed to address psychiatric issues fully in any patient. This approach is especially salient in epilepsy, where the obvious brain dysfunction inherent in epilepsy increases the risk of bias in the direction of the disease perspective and neglect of the other perspectives. This is in part because biological abnormalities associated with epilepsy can also be related to the genesis of psychiatric phenomena, for example, the location of the seizure focus, the presence of gross brain damage (as in head trauma or mental retardation), and the anti-epileptic medications themselves.8 Furthermore, neurochemical changes related to neuronal excitation and seizure inhibition may also predispose to certain psychiatric phenomena.9 However, cognitive and temperamental traits, behaviors, environmental factors, and psychosocial issues also contribute to psychiatric disturbance. In this review, we cite examples of psychiatric conditions that illustrate applications of each perspective, but remind the reader that the strength of this approach is the simultaneous application of all four perspectives. Epidemiology, Definitions, and Etiologies The prevalence of epilepsy is approximately 0.5%, and approximately 5%–10% of the population will have a seizure at some time in their lives.10 The incidence of epilepsy is highest in the first year of life, remains steady through midlife, and then peaks in elderly persons because of associations between epilepsy and vascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders. Men are affected slightly more than women.11 Given the myriad etiologies for epilepsy, seizures are best viewed as a symptom needing investigation rather than a diagnosis in itself. The various terms used to denote seizure types and epilepsy syndromes can be a source of confusion for clinicians who are not familiar with this topic. In part, this is because classification schemes for seizures and epilepsy syndromes have evolved over time and continue to be debated.12 The system currently accepted was developed by the International League Against Epilepsy (Table 1). 13 A seizure is defined as an abnormal paroxysmal discharge of cerebral neurons sufficient to cause clinically detectable events that are apparent either to the patient or to an observer. The diagnosis of epilepsy is reserved for a chronic neurological syndrome involving recurrent seizures, which excludes cases in which seizures are related to isolated febrile convulsions or systemic derangement, such as hypoglycemia. Also, the diagnosis of epilepsy is withheld when epileptiform abnormalities on the electroencephalogram (EEG) are not accompanied by clinical correlates. A number of factors contribute to the development of seizures and epilepsy syndromes, including genetic disorders, inherited syndromes, acquired conditions (traumatic brain injury), and various other situations that affect seizure threshold and predispose to epileptogenesis.14 However, the primary mechanisms causing epilepsy are not completely understood. View this table: TABLE 1. Classification of seizure types [in this window] [in a new window] The various epilepsy syndromes are associated with different etiologies, prognoses, medical and surgical treatments, and seizure types. Seizure types are usually classified as localized to a discrete portion of the brain (the focal or partial category) or generalized. Focal or partial seizures are often, but not always, associated with localized brain pathology. Focal seizures can be "simple," that is, without a change in the level of consciousness, or "complex," when there is clouding of consciousness or awareness. Auras, often mistakenly viewed as prodromal phenomena, are in fact simple partial seizures that may or may not transition into another seizure type. For a focal seizure, the seizure semiology (sequence of clinical manifestations) varies as epileptiform discharges propagate and involve different brain regions. Generalized seizures involve the entire cortex electrographically and can be convulsive or nonconvulsive. Focal seizures can progress into generalized seizures (secondary generalization). In primary generalized seizures, auras are usually not present. Assessment of psychopathology in epilepsy requires knowledge of the patient's specific epilepsy syndrome and whether there are special vulnerabilities to psychiatric dysfunction related to that particular epilepsy syndrome. Some data associate a higher incidence of psychiatric problems with focal epilepsy, especially of temporal lobe origin,15 although higher prevalence rates for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) than for other epilepsy syndromes confounds interpretations of such reports. Psychiatric phenomena can be associated with the seizure itself, as well as the peri-ictal and interictal phases of epilepsy. We will focus on the interictal period, since ictal and peri-ictal phenomena are temporally related to the seizure discharge and, therefore, once identified as such, are best treated by optimizing seizure control. However, the different phases are not always readily distinguished, especially since affective auras, ictal automatisms, postictal confusion, and mood lability can confound psychiatric assessment. EPILEPSY AND THE DISEASE PERSPECTIVE The diagnosis of epilepsy leads to the assumption that the brain has a "broken part," albeit unknown in many cases, that leads to abnormal propagation of brain electrical activity. The brain is also the substrate for psychiatric syndromes, and related disease processes appear to contribute both to epilepsy and to psychiatric conditions.16,17 Examples are major depression and panic disorder, which are more prevalent in epileptic patients than in the general population.4 Major Depression Reported rates for major depression in epilepsy are typically in the range of 30%, depending on the patient population and the diagnostic methods,18,19 with rates up to 50%.20 Although major depression is the more common problem,4 a retrospective chart review of patients with TLE found a 20% lifetime prevalence of mania, vs. 4% in a non-epilepsy control group.21 These rates are consistent with an increased prevalence of mood disorders associated with other primary central nervous system (CNS) disorders, including brain tumors, strokes, and HIV.5,22 Although sadness might be explained by demoralization secondary to the burdens of living with epilepsy (life-story perspective), a role for underlying brain pathology is implicated by higher rates of depression in epilepsy relative to comparison groups with non-CNS conditions and comparable levels of impairment.22,23 The location of the seizure focus is also relevant to the development of affective illnesses. Some studies report a higher prevalence of mood disorders in TLE than in other epilepsy types, supporting a specific role for temporal–limbic dysfunction in mood regulation.23–26 This finding has not been consistent, however.27 Hemispheric location of the seizure focus has also been an area of interest, especially in TLE. Several studies associate leftsided foci with an increased risk of depression and right-sided foci with an increased risk of mania.25,28–31 These findings parallel laterality findings for mood disorders after cerebrovascular events, tumors, and head injury.32–34 Mood disorders in epilepsy cause substantial morbidity and contribute to increased mortality. Compared with mortality rates in the general population, epilepsy patients have a fivefold higher rate of deaths secondary to suicide.35 Attempted suicides and self-injury are also more frequent.36 Reports on patients presenting after self-injury show an approximately sixfold overrepresentation of epilepsy patients compared with baseline rates for the general population.37,38 Panic Disorder The lifetime prevalence of panic attacks in patients with epilepsy is 21%,39 as compared with the 1% prevalence rate in the general population.40,41 Although this increased rate of panic attacks in epilepsy implicates underlying disease processes involving the limbic system,42 the disease perspective is also salient because interictal panic disorder represents a paroxysmal condition that can be misdiagnosed as an epileptic seizure.43 Conversely, anxiety symptoms and features of panic attacks can occur during seizures, and they need to be distinguished from interictal anxiety symptoms.44 Accordingly, failure to distinguish panic attacks from seizures can lead to inappropriate treatment with either anti-panic medications or higher doses of anti-epileptic medications. The disease perspective is readily applied to several other examples of psychiatric conditions that appear inherently associated with epilepsy-related disease processes. These include chronic and transient schizophrenia-like syndromes,45 cognitive dysfunction,46 and adverse psychoactive effects of anti-epileptic medications.47 Sedation, loss of energy, confusion, cognitive deficits, and delirium all warrant consideration using the disease perspective. One proposed mechanism for psychopathology in epilepsy is based on the observation of "forced normalization."48 "Forced normalization" refers to an EEG phenomenon in which better seizure control and a reduction in interictal epileptiform abnormalities are associated with the emergence of psychotic symptoms or other psychiatric complaints (mania or anxiety). The interictal psychiatric symptoms are usually transient, with remission of psychiatric dysfunction as seizures return and the EEG again shows interictal disturbances. One possibility is that neurochemical activity associated with seizures decreases the expression of psychiatric phenomena, whereas the neurochemical changes associated with seizure inhibition facilitate psychiatric symptoms.9 Kindling phenomena, although confirmed only in animals, are also proposed as relevant to temporal–limbic dysfunction and certain psychiatric complications of epilepsy in humans.17 EPILEPSY AND THE DIMENSIONAL PERSPECTIVE Among the four perspectives, temperament (or personality) and intelligence are viewed as "dimensional" in the sense that these characteristics in individuals are distributed along a continuum.7 In any individual, these characteristics are composed of assets and liabilities that, in their interactions with life circumstances, yield normal as well as abnormal emotional and behavioral responses. Where a person falls on the continuum of a given temperamental or intellectual trait influences vulnerability to psychiatric disturbances under stressful circumstances. Thus, a person's vulnerabilities are merely potentials until exposed by some provocation. In patients with epilepsy, inherent CNS pathology and the direct effects of anti-epileptic medications and seizures or postictal states affect intellectual and, potentially, temperamental attributes. However, the psychological experience of recurrent seizures can also be a significant stressor that brings out vulnerabilities. Temperament The notion of an "epileptic personality" has prevailed for many years, even though most patients with epilepsy are no more vulnerable to emotional problems due to their temperament than members of the general population. Some argue that descriptions of unique personality features among epilepsy patients were based on actual seizure phenomena or the effects of cognitive impairment, institutionalization, social stigma, intensified observation, medication side effects, and unrecognized comorbid psychiatric illnesses.5,49,50 The exception may be in some patients with seizures of temporal lobe origin whose personalities are classically described as "viscous" or "sticky," in reference to a ponderous, overly detailed, and circumstantial mode of communication that listeners tend to find tedious. This same style is evident in extensive written communication, referred to as hypergraphia. Decreased sexual interest (and, on rare occasions, increased sexual interest or fetishism) and religiosity are also observed in some patients with TLE.51 This dimensional model of personality stands in contrast to the categorical classification system of personality disorders exemplified by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual,52 which fails to capture gradations in a population and interactions between life events and personality vulnerabilities. With the stress-diathesis model, also referred to as the neurotic paradigm, Eysenck used factor analysis to determine core dimensions of personality.53 Of 39 personality traits studied, there were only two independent dimensions: introversion– extraversion and neuroticism–stability. Introversion–extraversion refers to the usual character of a person's emotional responses. Introverted qualities include slower emotional responses and a tendency to contemplate actions in terms of past events and future consequences, that is, primarily punishment-avoiding. Extraverted features include rapid but fleeting emotional responses, a focus on the present, and a tendency to be primarily reward-seeking. Neuroticism–stability describes the strength of emotional responses, with high neuroticism describing strong responses or potential instability. In the general population, the distribution of these dimensions reveals a normal distribution, or bell curve. Thus, temperamental features of most individuals are midrange between the extremes of each dimension. Fewer individuals are at the extremes, which confer greater vulnerability to psychopathology, especially when the individual is confronted with psychosocial stressors. Epilepsy and its associated burdens can expose such temperamental vulnerabilities, especially in patients who have personality traits at the extremes of a dimension. For example, a high-neuroticism (unstable) extravert will have a low threshold for tolerating medication side effects and less motivation for treatment when asymptomatic. Introverts are more likely to comply with treatment but can be more prone to anxiety. Accordingly, the differential diagnosis for mood symptoms such as sadness and anxiety requires consideration of the impact of life events for patients at different places on the personality dimensions. Intelligence The other important psychiatric dimension, intelligence, has special significance in the treatment of patients with epilepsy. Cognitive deficits in epilepsy related to brain damage reflect a "broken part" and should be viewed as the impact of a disease process on a psychiatric dimension. The onset of epilepsy early in life is often related to congenital, prenatal, or postnatal factors that are also associated with mental retardation or a range of learning difficulties. Later-onset epilepsy related to head trauma, tumor, stroke, degenerative processes, or CNS infections can be associated with circumscribed cognitive deficits or a global decline in cognitive functioning (dementia). Seizure type, laterality, age at onset, treatment response, and the presence of interictal EEG spikes are also risk factors for comorbid intellectual deficits.46,54,55 The impact of anti-epileptic medications on cognitive functioning is less clear, in part because of methodological problems in studies evaluating this issue.56 Some show a negative impact whereas others show benefit, probably through successful improvement in seizure control and subclinical EEG abnormalities. However, even though seizure control can be associated with better cognitive functioning overall, patients still have persistent cognitive deficits that are multifactorial in origin (e.g., inherent brain damage, effects of surgically resected brain tissue, or higher medication dosages). A given patient's ability to cope with these intellectual deficits is further influenced by temperament. For example, wordfinding or memory deficits may be more distressing to an anxious person (highneuroticism introvert) than to a more easygoing individual (stable extrovert). EPILEPSY AND THE BEHAVIORAL PERSPECTIVE Behaviors are actions defined by their consequences: they are goal-directed.7 For example, with the behavior of eating, the goal is ingestion of food. The details of how the food is obtained, prepared, and brought to the mouth vary widely from person to person. In the end, however, the consummatory act is fairly stereotyped. Some behaviors, such as eating, sex, and addictive drug use, are further motivated by underlying drive states that pose special challenges during treatment. There are also "non-motivated" behaviors, such as self-injury and abnormal illness behavior (hysteria). The behavioral perspective is concerned with motivated and non-motivated behaviors that are maladaptive, such as aggression, substance abuse, paraphilias, self-injury, eating disorders, and illness-related behavior. Aggression Aggression is a behavioral problem that is frequently attributed (rightly or wrongly) to epilepsy.57 Earlier in the 20th century, criminality was associated with epilepsy,58 an assumption that was probably related more to existing theories of criminality. Although it was known that not all epileptics were criminals, the diagnosis of epilepsy was considered in many criminals, even in the absence of a history of seizures. Then, classification schemes such as "latent epilepsy" and "epileptoid constitution" reinforced a notion that criminal behavior was related to a disease process and facilitated the separation of criminals from law-abiding citizens, a misapplication of disease reasoning. Although sudden and violent crimes were especially likely to be attributed to epilepsy, later studies failed to support this association after accounting for other psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse.59,60 It does appear, however, that aggression is more common in epilepsy patients with generalized brain damage,57 in which case it can be difficult to determine the relative contributions of epilepsy, social contexts, and the underlying brain damage to the behavior. Some studies do show a higher risk of incarceration among epilepsy patients relative to the general population, but it is usually for nonviolent crimes such as theft.61,62 Social factors contributing to perinatal complications or posttraumatic epilepsy are implicated.63 However, in a series of 105 murder cases, crimes without clear motivation were associated with a higher prevalence of EEG abnormalities and a thirtyfold increase in the diagnosis of epilepsy.64 Because the acts could not be explained by ictal automatisms or postictal confusion, two rare but occasional causes of criminal behavior,57 the significance of the finding is unclear. Nonetheless, extrapolations from it must be made with caution, lest we perpetuate stereotypes associated with epilepsy. Abnormal Illness Behavior The primary goal of abnormal illness behavior is to assume the sick role inappropriately in order to address some conflict or achieve some secondary gain, for example, attention or reduced expectations. Pseudoseizures, usually regarded as a form of conversion disorder, are a type of abnormal illness behavior that involves mimicking the behaviors of an ictal event. They tend to, but do not always, lack the usual features of epileptic seizures, such as a brief duration (30 to 90 seconds), tongue-biting or other injuries, incontinence, or postictal confusion.65 However, these features do not always occur during epileptic events, especially focal seizures, and the distinction between epileptic and nonepileptic seizures can be difficult. Furthermore, patients with actual epilepsy can manifest pseudoseizures or embellish epileptic events,66 and psychological stress can precipitate both epileptic and pseudoseizures.67 The occurrence of bilateral limb movements in clear consciousness is almost pathognomonic of pseudoseizures (although frontal lobe seizures are the exception68). Documentation of elevated serum creatine kinase and prolactin levels can also help with the differential diagnosis. The only way to definitively exclude pseudoseizures from the diagnosis is to demonstrate a lack of correlation with EEG findings. This often requires 24-hour video EEG monitoring and is a frequent reason for admission to epilepsy monitoring units.2 Treatment of pseudoseizures involves helping patients to resolve their conflicts in an adaptive fashion and in not reinforcing the pseudosymptom. Factors that initiate abnormal illness behavior may be quite different from their sustaining factors. Habit and the need to "save face" should not be ignored in the treatment of pseudoseizures. Major mood disorders, suicidality, and mental subnormality may also be relevant comorbid issues.65,69 EPILEPSY AND THE LIFE-STORY PERSPECTIVE The life-story perspective focuses not on what patients have (disease perspective), nor on what patients are (dimension perspective), nor on what they do (behavior perspective), but on what they encounter. The application of the life-story perspective involves getting to know the patient as an individual. It involves a commitment of time that is becoming more and more difficult in this age of managed care with 7 -minute-long office visits. Sometimes the events that patients encounter in their lives lead to demoralization, a state of helplessness, hopelessness, confusion, and subjective incompetence.70 Demoralization is typically treated through one of the various forms of psychotherapy. Through psychotherapy, patients learn a conceptual framework that allows them to attribute new meanings to life-events and therefore lessen demoralization.71 In its most straightforward form, supportive psychotherapy, the aim is to help the patient to focus on abilities instead of burdens and obstacles, and develop new coping strategies. Support groups and advocacy organizations can also be critical in combating demoralization. Many burdens and obstacles confront the patient with epilepsy. Stigma associated with epilepsy and the seizures themselves can interfere with social contacts. Classmates can become frightened if they witness a seizure at school. Unpredictable loss of control over bodily functions can be embarrassing, and adolescents may find it difficult to develop friendships. For example, patients may fear having a seizure while on a date. The prohibitions on driving and other burdens during this stage of life (adolescence) become obvious. Such disruptions in social development can continue throughout life, with difficulties achieving intimate relationships and problems with employment. Patients miss work because of seizures, postictal symptoms, and doctor appointments. Even without prejudice in the workplace, certain careers may not be available, (e.g., airline pilot) particularly those in which seizures create a dangerous risk to the patient or others. In addition to the social ramifications of epilepsy, there are burdens of taking medications, often several times a day, and enduring their side effects or consequences of missed doses. In general, patients must be prepared to remain on anti-epileptic medications indefinitely. Yet, phenytoin can cause gum hypertrophy that may require surgical correction. Valproic acid can cause hair loss, acne, and weight gain. Almost all of the anti-epileptics can cause sedation; and these are the supposedly tolerable side effects. There are also risks of drug-induced hepatitis and blood dyscrasias from many of the medications, necessitating frequent blood tests. We list these examples, not to be pessimistic—quite the contrary. We list them to encourage clinicians to spend the time to get to know their patients, understand their burdens, and help them cope with them. It is a mistake to start someone who is sad on an antidepressant unless there has been a thorough evaluation with consideration of the possibility of a perspective other than disease. TREATMENT Many of the principles guiding psychiatric treatment in patients with epilepsy are similar to those used for patients without epilepsy. With the methods described here, a comprehensive treatment plan can be devised that involves all four perspectives. As an example, we will consider the treatment of sadness in a patient with epilepsy and major depression. Treatment will probably include use of an antidepressant medication and possibly an antipsychotic medication if psychotic symptoms are present interictally. This use of medications is based on the disease perspective, and an extensive review of the pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy is available.72 The potential role for anti-epileptic medications in the treatment and causes of psychopathology47 and drug–drug interactions also needs to be addressed. Illness behavior may increase during exacerbations of depression, and risk of suicidal behavior needs to be considered. Tricyclic medications and large supplies of medications are typically not prescribed for patients with histories of self-injury, especially if by overdose. When selecting psychiatric medications, we need to consider the dimensional perspective as another factor. Complicated medication regimens are best avoided in patients who have low intelligence or temperamental vulnerabilities that increase the risk of poor adherence. Patients with epilepsy may be contending with the stigma associated with that diagnosis. Accepting the additional diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder may compound the stigma. Psychotherapeutic interventions, such as cognitive–behavioral and supportive therapies, are often necessary to address these issues, confront demoralization, and bolster the effectiveness of antidepressant medications. CONCLUSIONS The four psychiatric perspectives outlined in this article provide a method for assessing psychiatric issues in patients with epilepsy. Although not exhaustive, the examples cited demonstrate the utility of this approach. The advantage of this method is that it ensures that critical aspects of a case are not overlooked and that the reasoning of one perspective is not misapplied to a problem that is best viewed through the lens of another. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant MH53485 to Dr. Marsh. REFERENCES 1. Osler W: Aequanimitas. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1906, p 134 2. Blumer D, Montouris G, Hermann B: Psychiatric morbidity in seizure patients on a neurodiagnostic monitoring unit. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:445– 456[Abstract] 3. Neppe V, Tucker GJ: Modern perspectives on epilepsy in relation to psychiatry: classification and evaluation. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1988; 3:263–271 4. Ring HA: Epilepsy, in Psychiatric Treatment of the Medically Ill. Edited by Robinson RG, Yates WR. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1999, pp 371–389 5. Lishman WA: Organic Psychiatry: The Psychological Consequences of Cerebral Disorder. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Science, 1998 6. Marsh L: Psychiatric disorders in women with epilepsy, in Women With Epilepsy: A Handbook for Women With Epilepsy, Their Family and Friends. Edited by Morrell MJ. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press (in press) 7. McHugh PR, Slavney PR: The Perspectives of Psychiatry. Baltimore, MD, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998 8. Reynolds E: Biological factors in psychological disorders associated with epilepsy, in Epilepsy and Psychiatry. Edited by Reynolds EH. Edinburgh, Scotland, Churchill Livingstone, 1981, pp 264–290 9. Engel J Jr: Neurochemical disturbances in epilepsy: relationship to behavior, in: Epilepsy and Behavior. Edited by Devinsky O, Theodore WH. New York, WileyLiss, 1991, pp 335–343 10. Hauser WA, Rocca WA: Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 1996; 71:576–586[Medline] 11. Hopkins A: Definitions and epidemiology of epilepsy, in Epilepsy. Edited by Hopkins A. New York, Demos, 1987, pp 1–17 12. Benbadis SR, Lüders HO: Epileptic syndromes: an underutilized concept. Epilepsia 1996; 37:1029–1034 13. Commission on classification and terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy: proposal for revised classification of epilepsies and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia 1989; 30:389–399[Medline] 14. Engel JJ: Concepts of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1995; 36(suppl 1):S23–S29 15. Fenwick P: Epilepsy and psychiatric disorders, in Epilepsy. Edited by Hopkins A. New York, Chapman and Hall, 1987, pp 511–552 16. Post RM, Weiss SR, Clark M, et al: Seizures as an evolving process: implications for neuropsychiatric illness, in Epilepsy and Behavior. Edited by Devinsky O, Theodore WH. New York, Wiley-Liss, 1991, pp 361–387 17. Smith PF, Darlington CL: Neural mechanisms of psychiatric disturbances in patients with epilepsy, in Psychiatric Comorbidity in Epilepsy: Basic Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Edited by McConnell HW, Snyder PJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 15–35 18. Victoroff J: DSM-III-R psychiatric diagnoses in candidates for epilepsy surgery: lifetime prevalence. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1994; 7:87–97 19. Victoroff J, Benson F, Grafton ST, et al: Depression in complex partial seizures: electroencephalography and cerebral metabolic correlates. Arch Neurol 1994; 51:155–163[Abstract] 20. Indaco A, Carrieri PB, Nappi C, et al: Interictal depression in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 1992; 12:45–50[CrossRef][Medline] 21. Lyketsos CG, Stoline AM, Longstreet P, et al: Mania in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1993; 6:19–25 22. Kogeorgos J, Fonagy P, Scott DF: Psychiatric symptom patterns of chronic epileptics attending a neurological clinic: a controlled investigation. Br J Psychiatry 1982; 140:236–243[Abstract] 23. Mendez MF, Cummings JL, Benson DF: Depression in epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1986; 43:766–770[Abstract] 24. Shukla DG, Srivastava B, Katiyar BC, et al: Psychiatric manifestations in temporal lobe epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 135:411–417[Abstract] 25. Altshuler LL, Devinsky O, Post RM, et al: Depression, anxiety, and temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1990; 46:284–288 26. Perini GI, Tosin C, Carraro C, et al: Interictal mood and personality disorders in temporal lobe epilepsy and juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 61:601–605[Abstract] 27. Manchanda R, Schaefer B, McLachlan RS, et al: Interictal psychiatric morbidity and focus of epilepsy in treatment-refractory patients admitted to an epilepsy unit. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:1096–1098 28. Flor-Henry P: Psychosis and temporal lobe epilepsy: a controlled investigation. Epilepsia 1969; 10:363–395[Medline] 29. Bear D, Fedio P: Quantitative analysis of interictal behavior in temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Neurol 1977; 34:454–467[Abstract] 30. Perini GI, Mendius R: Depression and anxiety in complex partial seizures. J Nerv Ment Dis 1984; 172:287–290[Medline] 31. Strauss E, Moll A: Depression in male and female subjects with complex partial seizures. Arch Neurol 1992; 49:391–392[Abstract] 32. Starkstein SE, Robinson RG: Affective disorders and cerebral vascular disease. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:170–182[Abstract] 33. Jampala VC, Abrams R: Mania secondary to left and right hemisphere damage. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 152:246–252 34. Cohen MR, Niska RW: Localized right cerebral hemisphere dysfunction and recurrent mania. Am J Psychiatry 1983; 137:847–848[Medline] 35. Barraclough B: Suicide and Epilepsy, in Epilepsy and Psychiatry. Edited by Trimble MR. London, UK, Churchill Livingstone, 1981, 339–345 36. Gunn J: Affective and suicidal symptoms in epileptic prisoners. Psychol Med 1973; 3:108–114[Medline] 37. Mackay A: Self-poisoning: a complication of epilepsy. Br J Psychiatry 1979; 134:277–282[Abstract] 38. Hawton K, Fagg J, Marsack P: Association between epilepsy and attempted suicide. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1980; 43:168–170[Abstract] 39. Pariente PD, Lepine JP, Lellouch J: Lifetime history of panic attacks and epilepsy: an association from a general population survey (letter). J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:88–89 40. Eaton WW, Kessler RC, Wittchen HU, et al: Panic and panic disorder in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:413–420[Abstract] 41. Katerndahl DA, Realini JP: Lifetime prevalence of panic states. Am J Psychiatry 1993; 150:246–249[Abstract] 42. Hermann BP, Wyler AR, Blumer D, et al: Ictal fear: lateralizing significance and implications for understanding the neurobiology of pathological fear states. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1992; 5:205–210 43. Genton P, Bartolomei F, Guerrini R: Panic attacks mistaken for relapse of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1995; 36:48–51[Medline] 44. Young GB, Chandarana PC, Blume WT, et al: Mesial temporal lobe seizures presenting as anxiety disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1995; 7:352– 357[Abstract] 45. Sachdev P: Schizophrenia-like psychosis and epilepsy: the status of the association. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:325–336[Abstract/Free Full Text] 46. Glosser G, Cole LC, French JA, et al: Predictors of intellectual performance in adults with intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1997; 3:252–259[Medline] 47. Trimble MR: Anticonvulsants and psychopathology, in Psychological Disturbances in Epilepsy. Edited by Sackellares JC, Berent RS. Oxford, UK, Butterworth-Heineman, Ltd., 1996, pp 233–244 48. Landolt H: Serial electroencephalographic investigations during psychotic episodes in epileptic patients and during schizophrenic attacks, in Lectures on Epilepsy. Edited by Lorentz de Haas AM. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Elsevier, 1953, pp 91–133 49. Mungas D: Interictal behavior abnormality in temporal lobe epilepsy: a specific syndrome or nonspecific psychopathology? Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39:108– 111[Abstract] 50. Mendez MF, Doss RC, Taylor JL: Interictal violence in epilepsy: relationship to behavior and seizure variables. J Nerv Ment Dis 1993; 181:566–569[Medline] 51. Waxman SG, Geschwind N: The interictal behavior syndrome of temporal lobe epilepsy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1975; 32:1580–1586 52. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994 53. Eysenck HJ: Dimensions of Personality. London, UK, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1947 54. Mandelbaum DE, Burack GD: The effect of seizure type and medication on cognitive and behavioral functioning in children with idiopathic epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997; 39:731–735[Medline] 55. Weglage J, Demsky A, Pietsch M, et al: Neuropsychological, intellectual, and behavioral findings in patients with centrotemporal spikes with and without seizures. Dev Med Child Neurol 1997; 39:646–651[Medline] 56. Vermeulen J, Aldenkamp AP: Cognitive side effects of chronic antiepileptic drug treatment: a review of 25 years of research. Epilepsy Res 1995; 22:65– 95[CrossRef][Medline] 57. Fenwick P: The nature and management of aggression in epilepsy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 1989; 1:418–425[Abstract] 58. Lombroso C: Crime: Its Causes and Remedies. Boston, MA, Little Brown and Company, 1918 59. Astrom CH: A study of epilepsy in its clinical, social, and genetic aspects. Acta Psychiatrica et Neurologica Scandinavica 1950; 63(suppl 5):5–284 60. Juul-Jensen P: Epilepsy: a clinical and social analysis of 1,020 adult patients with epileptic seizures. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl 1964; 5(suppl):126–129 61. Gunn J, Bonn J: Criminality and violence in epileptic prisoners. Br J Psychiatry 1971; 118:337–343[Medline] 62. Gunn J, Fenton G: Epilepsy, automatism, and crime. Lancet 1971; 1:1173–1176 63. Rantakallio P, Koiranen M, Mottonen J: Association of perinatal events, epilepsy, and central nervous system trauma with juvenile delinquency. Arch Dis Child 1992; 67:1459–1461 64. Hill D, Pond DA: Reflections of one hundred capital cases submitted to electroencephalography. Journal of Mental Science 1952; 98:23–43 65. Peguero E, Abou-Khalil B, Fakhoury T, et al: Self-injury and incontinence in psychogenic seizures. Epilepsia 1995; 36:586–591[Medline] 66. Ramani SV, Quesney LF, Olson D, et al: Diagnosis of hysterical seizures in epileptic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1980; 137:705–709[Abstract] 67. Fenwick PB: The relationship between mind, brain, and seizures. Epilepsia 1992; 33:(suppl 6):S1–S6 68. Riggio S, Harner RN: Frontal lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1992; 5:283–293 69. Krumholz A, Niedermeyer E: Psychogenic seizures: a clinical study with followup data. Neurology 1983; 33:498–502[Abstract] 70. Frank JD, Frank JB: Persuasion and Healing. Baltimore, MD, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991 71. Slavney PR: Diagnosing demoralization in consultation psychiatry. Psychosomatics 1999; 40:325–329[Abstract/Free Full Text] 72. McConnell H, Duncan D: Treatment of psychiatric comorbidity in epilepsy, in Psychiatric Comorbidity in Epilepsy: Basic Mechanisms, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Edited by McConnell HW, Snyder PJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1998, pp 245–361