DITTSS (A Graphic Organizer for IOC):

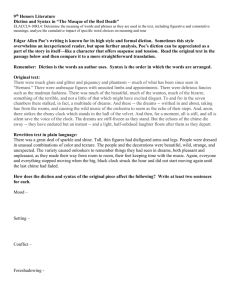

advertisement

DITTSS (A Graphic Organizer for IOC): Holman, C. Hugh, and William Harmon, eds. A Handbook to Literature. 6th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1992. Diction (p. 136): Sometimes used informally to refer to crispness of pronunciation. In linguistics, diction means word choice. As a translation of the Greek lexis, diction may also refer to the use of words in oral or written discourse, now ordinarily divided into vocabulary (words and other small units considered one by one in terms of plain or fancy, current or archaic, Germanic or Latinate, native or foreign, and so forth) and syntax (the order or arrangement of words considered as formal patterns construable as simple or complex, ordinary or extraordinary, loose or periodic, complete or fragmentary, and so forth). Some analysts speak of “level” of vocabulary and “texture” of syntax. The two constituents of diction permit independent classification, so that many of Robert Frost’s lines (such as “Something there is that doesn’t love a wall” and “Whose woods these are I think I know”) display simultaneously a marked simplicity of vocabulary but a marked oddness of syntax. Certain sorts of diction can become an author’s typical habit and distinctive stylistic signature, as in the combination of question and elliptical absolute found in may of W.B. Yeats’s most celebrated passages (such as “And what rough beast, its hour come round at last…” and “What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap…”). See POETIC DICTION. Imagery (p. 240-41): Imagery in its literal sense means the collection of images in a literary work. In another sense it is synonymous with TROPE or FIGURE OF SPEECH. Here the trope designates a special usage of words in which there is a change in their basic meanings. Patterns of imagery, often without the conscious knowledge of author or reader are taken to be keys to deeper meaning of a work. A few critics tend to see the “image pattern” as indeed being the basic meaning of the work and a better key to its interpretation than the explicit statements of the author or the more obvious events of plot or action. One notable contribution of the New Critics was their awareness of the importance of the relationships among images to the meaning of lyric poetry. Such patterning is important in fiction, as well, contrasting images of light and dark being among the most conspicuous. Tone (p. 477): Tone has been used, following I.A. Richards’s example, for the attitudes toward the subject and toward the audience implied in a literary work. Tone may be formal, informal, intimate, solemn, somber, playful, serious, ironic, condescending, or many another possible attitude. Tone or tone color sometimes designates a musical quality in language that Sidney Lanier discussed in The Science of English Verse, which asserts that the sounds of words have qualities equivalent to timbre in music. “When the ear exactly coordinates a serious of sounds with primary reference to their tone-color, the result is a conception of (in music, flute-tone as distinct from violin-tone, and the like; in verse, rhyme as opposed to rhyme, vowel varied with vowel, phonetic syzygy, and the like), in general…tone-color.” Technique (p. 472): The sum of working methods or special skills. Technique may be applied very broadly, as when one says, “The symbolic journey is a major technique in Joyce’s Ulysses,” or very narrowly to refer to the minutiae of method, or in an intermediate sense, as in STREAM-OFCONSCIOUSNESS technique. In all cases, however, technique refers to how something is done rather than to what is done. Technique, FORM, STYLE, and “manner” overlap somewhat, with technique connoting the literal, mechanical, or procedural parts of execution. Structure (p. 459-60): The planned framework of a piece of literature. Though such external matters as kind of language used (French or English, prose or verse, or kind of verse, or type of sentence) are sometimes referred to as “structural” features, the term usually is applied to the general plan or outline. Thus, the scheme of topics (as revealed in a topical outline) determines the structure of a FORMAL ESSAY. The logical division of the action of a drama (see DRAMATIC STRUCTURE) and also the mechanical division into acts and scenes are matters of structure. In a narrative the plot itself is the structural element. Groups of stories may be set in a larger structure plan (see FRAMEWORK-STORY) such as the pilgrimage in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The structure of an ITALIAN SONNET suggests first its division into OCTAVE and SESTET, and more minutely the internal plan of each of these two parts. A PINDARIC ODE follows a special structural plan that determines not only the development of the theme but also the sequence of parts. Often authors advertise their structure as a means of securing clarity (as in some college textbooks), whereas at other times their artistic purpose leads them to conceal the structure (as in narratives) or subordinate it altogether (as in some INFORMAL ESSAYS). In fiction, the structure is generally regarded today as the most reliable as well as the most revealing key to the meaning of the work. In the contemporary criticism of poetry, too, structure is used to define not only verse form and formal arrangement but also the sequences of images and ideas that convey meaning. The elementary basis of structure seems to be binary or binomial, a matter of contrastive relations that are differential, without positive or absolute terms. A perfected work of good art is a conspicuous example of foregrounded structure with many levels and sorts of organization (graphic, acoustic, grammatical, semantic, thematic, and so forth). A shapely work of art has both an endoskeleton and an exoskeleton: inward and outward structures. An entity inside a work of art generates its meaning and power within the well-marked limits of the work. Hamlet, for examples, means whatever he means inside the play as a complex function of many binary relations (with Horatio, Polonious, Laertes, Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, and so forth). Outside the play, as a portrait of a legendary Danish prince named Amlotha or as a self-portrait of Shakespeare or as an incarnation of an ill-resolved Oedipal fixation, Hamlet has no determinate meaning because those relations lack both structure and substance. See STRUCTURALISM. Style (p. 460): Style combines two elements: the idea to be expressed and the individuality of the author. From the point of view of style it is impossible to change the diction to say exactly the same thing; for what the reader receives from a statement is not only what is said, but also certain CONNOTATIONS that affect the consciousness. Just as no two personalities are alike, no two styles are exactly alike. It has been observed that even infants have individual styles. Even in so limited a medium as Morse code, each sender has a style, called a “fist.” A mere recital of some categories may suggest the infinite range of manners the word style covers: we speak, for instance, of journalistic, scientific, or literary styles; we call the manners of other writers abstract or concrete, rhythmic or pedestrian, sincere or artificial, dignified or comic, original or imitative, dull or vivid, low or plain or high. But if we are actually to estimate a style, we need more delicate tests than these; we need terms so scrupulous in their sensitiveness as to distinguish the work of each writer from that of all other writers, because, as has been said, no two styles are exactly comparable. A study of styles for the purpose of analysis will include, in addition to the infinity of personal detail suggested above, such general qualities as: DICTION, sentence structure and variety, IMAGERY, RHYTHM, REPETITION, COHERENCE, emphasis, and arrangement of ideas. There is a growing interest in the study of style and language in fiction. See PHENOMENOLOGY, SEMIOTICS, STRUCTURALISM.