Conducting Equality Impact Assessments in

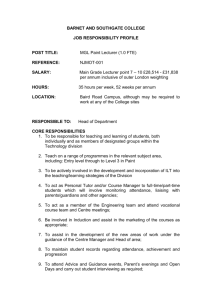

advertisement