Anglo Saxons (BBC)

advertisement

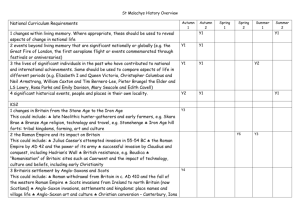

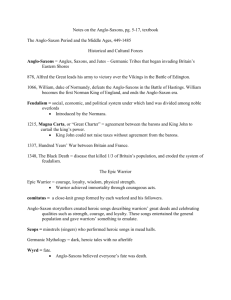

Anglo Saxons Reference: BBC Settlers in Britain The Romans invaded Britain in AD43. After that, for 400 years southern Britain was part of the Roman world. The last Roman soldiers left Britain in AD 410, and then new people came in ships across the North Sea. Historians call them Anglo-Saxons. The new settlers were a mixture of people from north Germany, Denmark and northern Holland. Most were Saxons, Angles and Jutes. There were some Franks and Frisians too. If we use the modern names for the countries they came from, the Saxons, Franks and Frisians were German-Dutch, the Angles were southern Danish, and Jutes were northern Danish. Outside Roman rule Roman Britain or 'Britannia' was part of the Roman Empire. It had Roman roads and Roman cities. Yet only southern Britain accepted Roman ways. The Picts and Scots, who lived north of Hadrian's Wall, remained outside the Roman world. The tribes of Germany and Scandinavia, such as the Saxons and Angles, were also outside the Roman Empire. The Romans called them 'barbarians'. Some tribes fought the Romans. Other tribes were happy to trade with the Romans, and some of their men joined the Roman army. How the Anglo-Saxons lived In their own lands, most Anglo-Saxons were farmers. They lived in family groups in villages, not cities. Since they lived close to the sea and big rivers, many Anglo-Saxons were sailors too. They built wooden ships with oars and sails, for trade and to settle in new lands. Raiders in ships attacked Roman Britain. Most people in Roman Britain were Christians. Most Anglo-Saxons were not Christians. They worshipped lots of gods and goddesses. Their beliefs were similar to those of the Celts, who lived in Britain before the Romans invaded. The Romans leave In the AD400s, towards the end of Roman rule, Britain was being attacked by invaders from the north and from the sea. The Romans had built forts along the coast to fight off the sea-raiders. These forts were called the 'Forts of the Saxon Shore'. The Roman Empire was very large and under attack in lots of places, so the Roman Army was not able to defend it all. About AD410, the Roman emperor ordered the last Roman soldiers in Britain to leave. The Britons would have to defend themselves as best they could. Hengist and Horsa Without Roman soldiers to defend them, the Britons were in danger from raids, so some British leaders paid Anglo-Saxons to fight for them. A history book called the 'Anglo-Saxon Chronicle' describes how in AD449 two Jutes named Hengist and Horsa were invited to Britain by a British king called Vortigern. He paid them and their men to fight the Picts. Instead, the Jutes turned on Vortigern and seized his kingdom. Hengist's son Aesc became king of Kent. No one knows if this is a true story, but it may show how some of the newcomers settled in Britain. Where did the Anglo-Saxons settle? When the Anglo-Saxons arrived in Britain, most kept clear of Roman towns. They preferred to live in small villages. However, warrior chiefs knew that a walled city made a good fortress. So some Roman towns, like London, were never completely abandoned. Many Roman buildings did become ruins though, because no one bothered or knew how to repair them. Some Saxons built wooden houses inside the walls of Roman towns. Others cleared spaces in the forest to build villages and make new fields. Some settlements were very small, with just two or three families. An Anglo-Saxon home In an Anglo-Saxon family, everyone from babies to old people shared a home. Anglo-Saxon houses were built of wood and had thatched roofs. At West Stow in Suffolk archaeologists found the remains of an early AngloSaxon village. They reconstructed it using Anglo-Saxon methods. They found that the village was made up of small groups of houses built around a larger hall. Each family house had one room, with a hearth with a fire for cooking, heating and light. A metal cooking pot hung from a chain above the fire. Clothing People wore clothes made from woollen cloth or animal skins. Men wore tunics, with tight trousers or leggings, wrapped around with strips of cloth or leather. Women wore long dresses. Women spun the wool from sheep and goats to make thread. They used a loom to weave the thread into cloth. Clothing styles varied from region to region. For instance, an Anglian woman fastened her dress with a long brooch. A Saxon woman used a round brooch. Clothing also changed over time. The dress in the pictures is the kind worn by Angles when they first arrived in Britain. What jobs did people do? Men, women and children helped on the farm. Men cut down trees to clear land for ploughing and sowing crops. Farmers used oxen to pull ploughs up and down long strip-fields. Children with dogs herded cattle and sheep. They kept a lookout for wolves - which still lived in Britain at this time. Some people had special skills. The smith made iron tools, knives and swords. Woodworkers made wooden bowls, furniture, carts and wheels. Potters made pottery from clay. The shoemaker made leather shoes. Jewellers made metal brooches, beads and gold ornaments for rich people. Why was Alfred so great? Great Anglo-Saxon kings included Offa of Mercia (who built Offa's Dyke) and Edwin of Northumbria (who founded Edinburgh or 'Edwin's burh'). But the most famous of all is Alfred, the only king in British history to be called 'Great'. Alfred was born in AD849 and died in AD899. His father was king of Wessex, but Alfred became king of all England. He fought the Vikings, and then made peace so that English and Vikings settled down to live together. He encouraged people to learn and he tried to govern well and fairly. King of the English Alfred became king in AD871. His elder brothers had each been king in turn before him, and he had been fighting the Vikings all his life. Alfred went on fighting the Vikings when all seemed hopeless. Finally, he won an important battle at Edington in Wiltshire in AD878. After that, some Vikings agreed to live in peace, though fighting still went on. Alfred's capital was Winchester. In AD886, his army captured London (which had belonged to Mercia before the Vikings seized it). By now Alfred was called 'King of the English' on his coins. This shows how important he was. Stories about Alfred One story says Alfred went to Rome at the age of 4, to meet the Pope. When he came home, his mother promised a handsome book to the first of her sons who could read it to her. Alfred learned it by heart, recited it, and got the book. Later the young King Alfred had to hide from the Vikings, on a marshy island called Athelney in Somerset. A famous story tells how while sheltering in a cowherd's hut, the king got a telling-off from the man's wife. Why? He let her cakes (or bread) burn. Another story says Alfred went into the Viking camp disguised as a minstrel, to find out what the Vikings were planning. How Alfred governed King Alfred was advised by a council of nobles and Church leaders. The council was called the witan. The witan could also choose the next king. Alfred made good laws. He had books translated from Latin into English, and translated some himself. He told monks to begin writing the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Alfred built warships to guard the coast from Viking raiders. He built forts and walled towns known as burhs. He split the fyrd (the part-time army) into two parts. While half the men were at home on their farms, the rest were ready to fight Vikings. Peaceful settlement? Some Anglo-Saxons came to Britain to fight, but others came peacefully, to find land to farm. The Anglo-Saxons knew Britain was a rich land. Their own lands often flooded, making it difficult to grow enough food. There was not enough land for everyone. Whole families set off across the North Sea in small boats. Each boatload of people formed a settlement with its own leader. They brought their tools, weapons, belongings and farm animals with them to Britain. The real King Arthur After the Roman soldiers left in AD410, Britain no longer had a strong army to defend it. There were battles between Anglo-Saxons and Britons. In AD491, for instance, a fight for the Roman fort at Pevensey in Sussex was won by the Anglo-Saxons, who killed all the Britons in the fort. Later people told stories of British leaders who fought the invaders. One was Ambrosius Aurelianus (a Roman name). Another was King Arthur. We do not know if there was a real Arthur. Most of the stories about him and his Knights of the Round Table come much later in history. Legend says Arthur won a great battle around AD500, but he could not stop more Anglo-Saxons coming. Where did the newcomers settle? Whether they settled peacefully, or drove the Britons from their lands, the Anglo-Saxons took control of most of Britain. However, they never conquered Scotland, Wales or Cornwall. The historian Bede, who lived in the 700s, wrote that Angles settled in East Anglia, the East Midlands and further north in Northumbria. Saxons moved in to Sussex (named after the 'South Saxons'), Essex (East Saxons), Middlesex (Middle Saxons) and Wessex (West Saxons). Jutes settled mainly in Kent, Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. How did England get its name? The Roman Britons spoke Latin or local Celtic languages. The newcomers spoke their own languages, which in time became a language now known as Anglo-Saxon or Old English. The Anglo-Saxons themselves called it 'Englisc'. The country taken over by the new settlers became 'England'. Some Britons settled down with the newcomers. Others moved west and north, taking their Latin-Celtic culture with them. Place names give clues to where the new 'English' lived. A place-name ending in -ham, for instance, shows it was once a Saxon settlement. Ham in Anglo-Saxon English meant 'village'. How Anglo-Saxons fought Anglo-Saxon armies were usually small, with only a few hundred men. The soldiers had spears, axes, swords and bows and arrows. They wore helmets on their heads and carried wooden shields. Everyone fought on foot during a battle. It must have been a bit like a giant rugby scrum, with lots of pushing and yelling, and nasty wounds. The most feared Anglo-Saxon weapon was a battle axe, but the most precious weapon was a sword. It took hours of work by a smith to craft a sword. He softened iron in a red-hot fire, twisted iron rods together and hammered the sword into shape. Part-time soldiers Most soldiers had farms, and after a battle went home as soon as they could, to look after their animals and crops. To make sure he had enough soldiers, the king ordered local officials called 'ealdormen' to provide so many men each. The more land you had, the more men you had to provide. These local bands of men made up England's part-time army called the fyrd. If the country was invaded, the king could call up every freeman to join his army. The warrior code The king had a small bodyguard of brave warriors who would die to defend him. The 'warrior-code' of the Anglo-Saxons taught that a warrior must fight and die for his leader, if he had to. An Anglo-Saxon poem called The Battle of Maldon tells the story of a battle in Essex in 991, between English and invading Vikings. The English leader allowed the Vikings to cross from their camp for a 'fair fight'. The English lost, but the poem still praises their heroism. Wars with the Vikings Viking attacks on Anglo-Saxon England started at the end of the AD700s. The Vikings came by sea in their longships. They attacked monasteries and churches to steal gold and other treasures. By the 800s, great armies of Vikings roamed England. In AD869, they killed King Edmund of East Anglia. After King Alfred of Wessex fought the Vikings, he made peace with them. He built ships and walled towns to defend his kingdom against Viking attacks. However, fighting between the English and the Vikings went on into the AD1000s. Early Anglo-Saxon beliefs In Roman Britain, many people had been Christians. The early Anglo-Saxons were pagans. Much like the Vikings of Scandinavia, they believed in many gods. The king of the Anglo-Saxon gods, for example, was Woden - a German version of the Scandinavian god Odin. From his name comes our day of the week Wednesday or 'Woden's day'. Other gods were Thunor, god of thunder; Frige, goddess of love; and Tiw, god of war. Anglo-Saxons were superstitious. They believed in lucky charms. They thought 'magic' rhymes, potions, stones or jewels would protect them from evil spirits or sickness. English and Vikings The English often called the Vikings "Danes" - though there were Swedish and Norwegian Vikings as well as Danish ones. Anglo-Saxon history tells of many Viking raids, from the time in 793 when Vikings attacked the monastery at Lindisfarne in Northumbria and killed many of the monks. After King Alfred led the fight against them in the 870s, some Vikings settled down to live peacefully. They had their own part of eastern England called the Danelaw. English and Danelaw Vikings became neighbours, though other Vikings went on raiding from the sea. Kings after Alfred the Great After Alfred, English kings gradually recaptured land from the Vikings. Alfred's son Edward won control of the Danelaw. Alfred's grandson Athelstan pushed English power north as far as Scotland. The most powerful Anglo-Saxon king was Edgar, who died in 975. Welsh and Scottish rulers obeyed him, and his court at Winchester was one of the most splendid in Europe. Anglo-Saxon England reached its peak during Edgar's reign. Vikings take the crown After King Edgar, things went downhill for the English kings. One not very good king was Ethelred the Unready (his name comes from an Old English word unraed, meaning "bad advice"). Ethelred tried to pay off invading Vikings with gold and land. It didn't work and he had to flee to France. After more fighting, a Dane called Cnut (Canute) became king of England in 1016. Cnut also ruled Denmark and Norway. He ruled well, but left much of the government in England to noblemen, now called "earls" (from the Danish word "jarl"). After Cnut died in 1035, two of his sons Harold and Harthacnut were each king in turn. King Edward and the earls In 1042 there was a new king of England. He was Edward, son of Ethelred the Unready. His mother, Queen Emma, was from Normandy, in France, and Edward spent most of his life in Normandy before becoming king. He was very religious and was called "Edward the Confessor" because he so often confessed his sins. Edward allowed the English earls, like Earl Godwin of Wessex, to become very strong. When Edward died in 1066, the English witan chose Godwin's son Harold as the next king. The Norman Conquest Harold had a rival. Duke William of Normandy said King Edward had promised that he would be the next king of England. William decided to invade England. In 1066, England was invaded twice. First, a Norwegian army led by Harald Hardrada landed in the north. Harold killed Hardrada in a battle at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire. Three days later William's Norman army landed in Sussex. Harold hurried south and the two armies fought the Battle of Hastings (14 October 1066). The Normans won, Harold was killed, and William became king. The story of how the Normans conquered England was told in the Bayeux Tapestry. The Anglo-Saxon period of English history was over. Battle of Hastings When Edward the Confessor died childless and the Witan (a national council of leading nobles and spiritual leaders) gave Harold Godwinson the throne William was so angry he invaded England. He believed Harold had promised him the throne. At the Battle of Hastings; 14th October 1066 King Harold lost. Harold was outnumbered, his troops were exhausted as they had just marched from the Battle of Stamford Bridge near York where they had defeated the King of Norway, Harald Hardrada and when the Normans pretended to run away Harold's army moved down from the safety of their hill. The Bayeux Tapestry, ordered for William by his brother, then shows King Harold being hit in the eye with an arrow and then being trampled on. Once Harold was dead, William won the battle Norman Castles William had to ensure that Saxons followed his orders. The first thing he did was put up castles to provide somewhere safe for the soldiers to live and to scare the Saxons as many had never seen a castle before. From Normandy William brought three prefabricated wooden Motte and Bailey castles that were quick to assemble. The Normans built 500 castles in the first year. Norman castles were increasingly made of stone so that they were very difficult to attack. William would not have won the Battle of Hastings without his well trained army. As a reward for their help William gave them land in England. In return they had to promise to fight for the King and pay taxes. It meant that William could quickly build up and pay for a large army if he was attacked. Most Normans who were given land built castles to show the local people who was in charge. The Domesday Survey In 1086 William needed money to equip his army so to find out if landowners were paying the correct amount of tax he introduced the Domesday Survey. This recorded types of land and animals owned and how much money the owner made and if that amount had changed between King Edward's reign and 1086. When all the information was written down it became known as the Domesday Book. Celebrations and Food The Normans would celebrate important events such as Christmas or May Day with lavish feasts. At Feasts, guests were not only seated and given food according to their position but they were also given different cutlery, bowls and glasses. For the Nobility roasted peacocks and wild boar with spicy sauces, Jellies and custards dyed bright colours, Sotiltees, (sugar sculptures), made to look like castles were all placed together on the dinner table. Peasants ate food that had been salted or pickled to preserve it including pickled herring and bacon and potage, a thick vegetable soup, with bread. Peasants drank ale rather than the wine favoured by nobles. Large thick slices of stale bread called trenchers were used by some people as plates. In large houses travelling acrobats, jesters or players (actors) were often hired. Minstrels would sing and play from a raised gallery above the great hall where the feast would take place.