Author: Published Date: Title: Writing Readable Texts: Evaluation of

advertisement

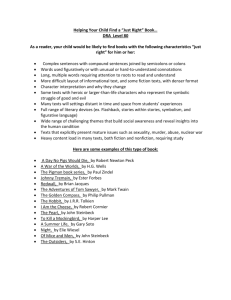

Author: Published Date: Title: Writing Readable Texts: Evaluation of the Ekarv Method Publisher: Place Published: Page Numbers: Museum Practice: Interpretation. England Pages 72 - 73 WRITING READABLE TEXTS: EKARV'S THEORY Margareta Ekarv developed her theory while writing exhibition texts for the Swedish Postal Museum. She based her method on experience gained during an earlier commission to write books for adult literacy classes. Observing how museum visitors read texts - often in poor light, while standing up, and in a distracting, sometimes noisy environment - she recognised similar difficulties of concentration and comprehension to those experienced by people with low literacy skills. She experimented with the very simple format of the books to express the much more complicated information contained in the museum exhibition. Ekarv recommends a structured and organic style of writing (box 2). She encourages the use of words `to give a new, deeper dimension to our visual experience' (Ekarv, 1987). She emphasises the importance of close co-operation between the writer, curator and designer of the exhibition, so that each understands the others' objectives and the texts become an organic part of the whole display. EVALUATION OF THE EKARV METHOD Swedish writer Margareta Ekarv believes it is possible to write museum texts, which are so easy and attractive that readers will both, enjoy and learn from them. Recent evaluations of her method by Jennifer Sabine at Swansea Museum and Elizabeth Gilniore at Nature in Art have endorsed most of her claims and shown a positive response from museum visitors. SWANSEA MUSEUM Jennifer Sabine used Ekarv's method to write texts for a new Egyptology gallery and evaluated the results for her MA dissertation at the University of Leicester. THEORY INTO PRACTICE The new gallery at Swansea Museum contains an Egyptian mummy and a coffin, which after over 100 years on display, has recently undergone conservation. The mummy's absence and return excited local interest not only in Egyptian history and the identity' of the mummy, but also in the conservation work itself. This prompted our decision to include information about conservation alongside the historical interpretation of the mummy. The texts had to be appropriate to readers ranging from primary school children studying Ancient Peoples to adults with an amateur or specialist interest in Egyptology. When writing these texts, 1 followed Ekarv's guidelines faithfully (box 2). The information was divided into themed sections about the mummy, its provenance and historical background, and the conservation work it had undergone. I enjoyed the discipline writing so precisely, searching for the one word, which is both expressive and simple. Critical editing and the collaboration of my colleagues helped to avoid confusion and ambiguity; reading the passages aloud to them helped to catch the flow and rhythm of natural speech. EVALUATING THE TEXTS Questionnaires given to visitors before the gallery opened asked them to compare a text written according to Ekarv with a more traditional one(box I) and to indicate their preference from a variety of layouts. In each case, the text written in Ekarv's style proved the most popular. Responses showed that readers had understood these texts and in the main approved of their unconventional layout they also found them easier to read. The age groupings of respondents showed that a majority of adults enjoyed Ekarv's style. Among younger age groups, teenagers mainly preferred traditional formats but young children liked the Ekarv text; possibly because teenagers usually read more traditional material, such as textbooks and novels, while young children's books are designed primarily for ease of reading. The most engaging part of the project was studying visitors' reactions to the new gallery after it opened, using qualitative research methods. Focused observation of visitors behaviour in the gallery, using the museum's CCTV security monitors, showed that 75 percent of visitors read some of the texts, an unexpectedly high proportion. Of these, over half read for more than two minutes and almost all referred back to the texts while viewing the objects. This suggested that if people find reading easy they will continue to read and will use texts to interpret objects. A more precise and detailed assessment of visitors reactions was gained from interviews and written comments. These were largely Favourable: only eight of the 52 respondents were positively critical and 11 mildly critical or neutral. A few identifiable themes emerged: The short lines, complete in themselves, and the well-separated blocks of text seem to facilitate reading. Some people had not noticed the unusual format used, others referred to it as "like a poem": some liked this, but a few found it odd, even irritating. ln general, readers liked the informal and rhythmic quality. Several said they did not usually read in museum texts but had read these, and enjoyed them The simple wording was not considered to be patronising and many visitors appreciated being able to read the short lines and paragraphs without much effort - this was particularly true of older people, I could read without my glasses' was a frequent comment. The texts were also translated into Welsh in line with Swansea Museum's bilingual policy. Two native speakers and a Welsh learner, who were asked to read the translations, with Ekarv's guidelines in mind, confirmed that her principles could be successfully maintained in translation. CONCLUSION Ekarv's style of texts has proved successful in Swansea Museum. In 1996 the Egyptology gallery won the Museums and Galleries commission Award for communicating conservation, and was also commended ill the Interpret Britain Award 1996. But the strongest endorsement of Ekarv's method is that visitors can be heard reading the texts aloud to one another quite comfortably, and quilting from them in conversation. EXAMPLES OF TEXTS USED FOR EVALUATION. "Traditional" style of museum text. The "Ekarv" interpratation of the same text.