Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research

advertisement

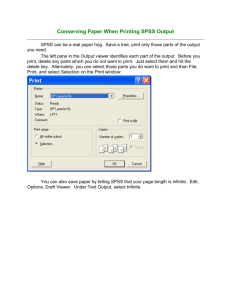

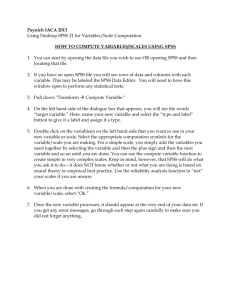

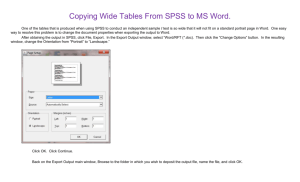

Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Course Data Number: Title: Credit-hours: Department: School/College: Type: PHMS-702 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research 3 Health Management and Systems Sciences School of Public Health and Information Sciences Lecture Catalog Description An overview of quantitative research methods for evaluating population health, including evaluations of comparative efficacy of medical interventions, psychometrics for assessing questionnaires, and effectiveness of clinical preventive and practice guidelines. Course Description This course is about methods for measuring varieties of quality in healthcare: methods to assess the quality of published research, examining context and quality of standardized questionnaires for health-related quality of life (HRQL) assessments, and investigating effectiveness of programs / applications / policies to improve the quality of care, health status of populations, etc. We examine quality from multiple perspectives – individuals in the context of their daily social roles, for example, and examining quality perspectives through the lens of organizations with intentions to change the healthcare system, focusing on case studies of the Wagner’s chronic illness care model, models for pay-for-performance and other current topics. Hands-on computer applications in quantitative research methods are present during the last hour, including skills for hypothesis testing, mathematical modeling and interpretation of common statistical tests, using analytic softwares like SPSS and Excel on existing datasets. Course Objectives Upon completion of this course, the successful student is able to: Describe differences in approaches to health services research, including primary data collection, secondary analysis of existing datasets, and hypothesis-free data mining. Identify, describe, and discuss the content, strengths, and limitations of some commonly used questionnaires used to measure functional status, person-centered health status, and health-related quality of life Describe, interpret, and discuss basic psychometric properties of questionnaires for reliability, types of validity, and responsiveness of health-related quality of life assessments, including measures among those with impairments, disabilities, and handicaps Page 1 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Describe processes about how to conduct a systematic review, especially in relationship to processes for developing clinical preventive guidelines and clinical practice guidelines Discuss methods for mathematical modeling as the basis for statistical risk adjustments (including, for example, indicators for physiologic risk, socio-demographics, comorbidities, severity of disease, severity of illness, and case-mix) as potential confounders in health services research Discuss applications of health services research methods for quality improvement, benchmarking, performance profiling, public reporting, and pay for performance Apply basic skills for data analysis, presentation, editing, and interpretation of statistical data, using Excel and SPSS software. Prerequisites Enrolled in health management concentration of public health sciences Ph.D. program, or permission of instructor. Course Instructors Name Robert Wm. Prasaad Steiner, M.D., MPH, Ph.D. Course Director Office SPHIS 115 Phone 502-852-3006 Email r.steiner@louisville.edu The course director welcomes conversations with students outside of class. Students may correspond with the instructor by email or set up appointments. Students should also contact the course director with questions they might have regarding the mechanics or operation of the course. Page 2 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Course Topics and Schedule IMPORTANT NOTE: The schedule and topics may change as the course unfolds. Changes are posted on Blackboard. CLASS 1 TOPICS Introduction to the Course What is Health Services and Outcomes Research? Scope of HSOR – Medical Effectiveness, Organized Medicine, Improving Population (Community) Health, Relation HSOR to Health Policy Development and Assurance; Health Systems: Individuals and Organizations, Technologies and Culture, Access Quality and Costs – Video NIH: Health Services Research – A Historical Perspective Selections from 48 min total HSOR: Efficacy or Effectiveness? Relevance to Clinical Research? Health Management? Systems Sciences? PHCI 602: Emphasis on assessments and measures of quality Application: Personal laptops, SPSS ver17, Getting Started; Importing Data sets Wagner, Chapter 1: Overview ACTIVITIES ( = Included in student evaluation) Pre-test Contact Information OVID Demo for Literature Search Methods: Access to pdf for required readings with Endnote x2 library documents Students bring PC to class with SPSS ver. 17 loaded and ready Upload a dataset from Blackboard SECTION I: HSOR Methods for Mathematical Modeling 2 Basics of Mathematical Modeling: RQ and Hypothesis Testing; Bias and Error, Hierarchy of Study Designs, Causality Method for analyses: Selection of Variables and Univariate Analyses, Levels of Data, Measures of Central Tendency, Parametric and NonParametric methods for frequency Bivariate Analyses and Correlations (Spearman and Pearson), Reducing the pool of variables for modeling with liberal threshold for p-values, Measures of Association (OR and RR) 3 Application: Wagner, Chapter 2: Transforming Variables Levels of Data; Recoding and categorizing Basics of Mathematical Modeling: Hypothesis Testing; Bias and Error, Hierarchy of Study Designs, Causality Multivariate Analysis: Classical and Logistic Regression Analyses; Research Goals: Determine Components for Highest R2 Value for a Model and/or ID most important factors to predict an outcome. Modeling Direct effects w and w/o statistical interaction. Backward method. Assessing Confounding, Tables, Interpretation of Results, Pvalues and Confidence Intervals Describe variables in a dataset Recode a variable Quiz 1 on required readings and classroom discussions from classes 1 and 2 Make a table of variables Application: Wagner, Chapter 3: Selecting Samples and Cases Univariate Analysis: Range checks; Describing the data Page 3 of 14 Transfer data to Excel and/or Word Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research CLASS 4 Introduction to Risk Adjustment as Confounding Methods for age adjustment as an example Recognizing confounding by comparing results: Comparing OR in Crude and Adjusted Models Standard Million method for Age Adjustment; Application: Wagner, Chapter 6: Cross Tabs & Measures of Association Bivariate Analysis: Cross Tabs, OR 6 ACTIVITIES ( = Included in student evaluation) TOPICS Introduction to Risk Adjustment 5 PHMS-702 Age Adjustment with Excel Risk Adjustment: Social Gradient of Health: Race Class or Opportunity? Comorbidities (Charlson Index), Severity (ASA Scores, APACHE II, III and others) and Case Mix (Groups of DRGs); Policy evaluations with assessing data before and after intervention: When to use time series analyses Students sign up Risk Adjustment Presentation in Class 6 Students pairs sign up (or assigned) database reports teams in Class 7 Generate an OR with CI(95) in SPSS Age Adjustment with Excel Application: Wagner, Chapter 5: Charts and graphs P-values and CI (95); Bar charts for HRQL by SES Bar charts for HRQL by SES Student Presentations about Measures for Risk Adjustment Student Reports about Risk Adjustment Application Wagner, Chapter 5: Charts and Graphs Obj.: Generate Bar Charts for HRQL scores by quartiles of SES Bar Charts for HRQL scores by quartiles of SES Student Reports about National Datasets Transfer SPSS output to Word. Transfer SPSS output to Excel. SECTION II: HSOR Quality Measures in Healthcare for Populations 7 Selecting Indicators and Reporting Results for Health Report Cards; Measures of Frequency, Association and Impact; Do we need CI(95) in enumerated measures? Sources of Data; Primary and Secondary Analyses; Student Presentations about National Datasets 8 Application Wagner, Chapter 4: Organization and Presentation of Information Obj.: Transfer SPSS output to Word. Transfer SPSS output to Excel. Vital Statistics: Birth and Death Certificates Examining the Exposure-Disease (E-D) Associations in Public Health Quality of Data for Outcomes in PH: Accuracy of Death Certificates: Autopsy as Gold Standard Read Online: Completing Death Certificates http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf Application Wagner, Chapter 7: Correlation and Regression Mathematical Modeling and Statistical Interaction Page 4 of 14 Spearman and Pearson correlation; CI (95) Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research CLASS 9 TOPICS Benefits of the Birth Cohort Method Quality of Data for Accuracy of Exposure Status: Maternal Reports about Prenatal Smoking PHMS-702 ACTIVITIES ( = Included in student evaluation) Quiz 2: Death certificates, required readings, and classroom discussions Application Wagner, Chapter 9: ANOVA Simple and Multivariable regression analysis in SPSS SECTION III: Measuring Health and Improving Quality of Care 10 Systematic Reviews: What works? Interpreting Meta-analysis EBM and Guideline Development: Ex Cochrane & USPSTF Are CPGs effective? Need for translational research Karl Popper and Philosophy of Science; Deduction and Induction; Systems Dynamics; Complexity: Emergence and Self-Organization Sign up Student-Pairs select one HRQL questionnaire: EQ-5D, SF6D, HUI-2 or -3, QWB-SA, ALOL for presentation Class 12; may also include CDC H-Days, PQOL How these perspectives relate to HSOR 11 Application Reliability coefficients Psychometrics: Measures of Validity and Reliability Measuring Depression Reliability coefficients Cronbach’s and other Kappa Coefficient; Transfer data from SPSS to Word for editing in Text Student present HRQL questionnaires content: EQ-5D, SF6D, HUI-2 or -3, QWBSA, ALOL for presentation Class 12; may also include CDC H-Days, PQOL Prevalence of Disease Influences the Results of Screening; Serial Screening; Adjusting for Depression Comparing Outcomes for Measures for Depression (CESD & PHQ) Improving Accuracy of Questionnaires with Serial Testing 12 Application Wagner, Chapter 10: Editing Output Student present HRQL questionnaires content: EQ-5D, SF-6D, HUI-2 or -3, QWB-SA, CDC H-Days, PQOL HRQL and Content Validity: Same Name – Different Items: Examining Content of Quality of Life Questionnaires in Outcomes Research Recent events: Short forms, Proprietary measures; Variability Response Options: Frequency- or Intensity-based What is important for a good quality of life? Introduction to Positive Health, Self Efficacy, LOC Functional Health: New and Old Taxonomies for Impairment, Disability, Handicap; Measurement Instruments: ADL IADL Application Wagner, Chapter 11: Advanced Applications Page 5 of 14 TBA (and not handed in) Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research CLASS 13 TOPICS Change scores with HRQL questionnaires: Within person Responsiveness, Meaningful Differences, JND, Minimally Clinically Important Differences; Anchor and Distributive Methods Estimating Effect Size 14 Application Estimating Effect Size Quality of Care: Quality Improvement Initiatives Processes for Quality Indicators, Public Reporting and Pay for Performance Profiling Clinical Performance: What is it? Why do it? Does it work? PHMS-702 ACTIVITIES ( = Included in student evaluation) Quiz 3 : psychometrics, variation in HRQL instruments, and required readings and classroom discussions Estimating Effect Size Receive Article and Questions as Take-Home Final Exam Final Exam is due 5 days later Submit SPSS results page Change Management: Proposals for changing funding stream PCMH Application Wrap Up Submit SPSS results page NOTE: The first two hours of this course are taught in conjunction with PHCI-602 “Health Services and Outcomes Research.” The last hour is on applications and computer demonstrations, which are not part of PHCI-602. Course Materials Blackboard The primary mechanism for communication in this course, other than class meetings, is UofL’s Blackboard system at http://ulink.louisville.edu/ or http://blackboard.louisville.edu/. Instructors use Blackboard to make assignments, provide materials, communicate changes or additions to the course materials or course schedule, and to communicate with students other aspects of the course. It is imperative that students familiarize themselves with Blackboard, check Blackboard frequently for possible announcements, and make sure that their e-mail account in Blackboard is correct, active, and checked frequently. Required Texts William E. Wagner, III. Using SPSS for Social Statistics and Research Methods, Second Edition. Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks California, 2010. Other Required Reading The required reading by class is available in Blackboard and is drawn from journal articles and other sources. A sample of the required reading list is in Attachment 1. Page 6 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Additional Suggested Reading The suggested reading by class is available in Blackboard and is drawn from journal articles and other sources. A sample of the suggested reading list is in Attachment 2. Prepared Materials Used by Instructors Materials used by instructors in class are available to students via Blackboard no later than 24 hours following the class. These may include outlines, citations, slide presentations, and other materials. There is no assurance that the materials include everything discussed in the class. Other Materials All students are required to have a PC with minimal specifications as per SPHIS policies (See https://louisville.edu/it/services/software/school-of-public-health-and-informationsciences.html/document_view ). Student should bring their laptops to class with SPSS ver. 17 loaded for use during the last hour, or applications section, of each class. Additional required softwares: SPSS ver. 17. A CD of SPSS ver. 17 may be purchased as a companion to Wagner’s text for a small extra charge. According to the publisher, the license for that version of SPSS is valid for four years. This is longer than the duration of license and access for SPSS versions purchased through UofL IT Express (due to more aggressive updating policies at UofL). Student may choose to purchase of SPSS using either of these or other options. Course Policies Attendance and Class Participation Attendance in class is highly encouraged. Unexcused absences will result in lower evaluation scores. The philosophy of education for this course is that learning is an interactive process that is engendered through participation in discussions and other participatory exercises. Concepts that support learning objectives are discussed and developed during class time, and supported again through other assigned learning activities, such as classroom presentations, statistical applications, reading assignments and homework. As such, active class participation is expected. Students are expected to arrange for excused absences before class by talking with the course director or co-directors, and by making an e-mail request before the absence, if possible. Communications after the fact are acceptable in some situations, including for example acute illnesses and personal emergencies. The course director encourages partners for learning exercises and presentations to promote peerto-peer learning. Page 7 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Student Evaluation The components of student evaluation are: 1. Participation in classroom discussions. This component is evaluated using the following rubric and is applied to each student in each class. If a student is absent from class without prior arrangement with the course director, the student’s score for that class is 0. (10% of final grade) RUBRIC FOR PARTICIPATION IN CLASSROOM DISCUSSION Criterion Assessment of Criterion (Note: Assigned score within a range is assessment of degree criterion is met.) Exceeds expectations (range 9.0-10.0) Often cites from Integration of reading reading and Uses reading to exercises support points into Often articulates fit classroom of reading with discussions topic at hand (weight) (4.0) Always a willing participant Responds frequently to questions Routinely volunteers point of (4.0) view Always demonstrates Demonstration commitment through thorough of preparation professional attitude and Always arrives on demeanor time Often solicits (2.0) instructor’s perspectives outside class Interaction and participation in classroom discussions Meets expectations (range 8.0-8.9) Occasionally cites from reading Sometimes uses reading to support points Occasionally articulates fit of reading with topic at hand Often a willing participant Responds occasionally to questions Occasionally volunteers point of view Rarely unprepared Rarely arrives late Occasionally solicits instructor’s perspectives outside class Below Not acceptable expectations (range 7.0-7.9) (range 0.0-6.9) Rarely able to cite Unable to cite from from reading readings Rarely uses Unable to use readings to support reading to support points points Rarely articulates Unable to fit of readings with articulate fit of topic at hand readings with topic at hand Rarely a willing Never a willing participant participant Rarely able to Never able to respond to respond to questions questions Rarely volunteers Never volunteers point of view point of view Often unprepared Occasionally arrives late Rarely solicits instructor’s perspectives outside class Rarely prepared Often arrives late Never solicits instructor’s perspectives outside class Gross points for participation in classroom discussions (maximum of 100) Crit. Score Topic Points Wt. (= Crit. Score x Wt.) x4.0 = x4.0 x2.0 = ∑ Weight of participation in classroom discussions in final grade (10%) Point contribution of participation in classroom discussions to final grade (maximum of 10) = x 0.1 = 2. Quizzes. There are three quizzes. (total of 30% of final grade) Quiz 1 in class 3 on required readings and classroom discussions in classes 1 and 2 (10% of final grade) Quiz 2 in class 9 on death certificates, required readings, and classroom discussions (10% of final grade) Quiz 3 in class 13 on psychometrics, variation in HRQL instruments, and required readings and classroom discussions (10% of final grade) Page 8 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 3. Class presentations. There are three class presentations, each of which is evaluated using the rubric below. (total of 30% of final grade) Class presentation in class 6 on measures for risk adjustment. Students in pairs or individually select generic HRQL questionnaires (see table below) to assemble psychometric data and to review content and research results. (10% of final grade) 1. Medical Outcome Study Short form MOS SF12 3. WHO Quality of Life - Brief Form WHOQOLBREV 5. Quality of Well Being – self administered QWB- 2. Perceived Quality of Life PQOL 4. Sickness Impact Profile SIP 6. Nottingham Health Profile NHP 12SA 7. European Quality of Life EQ-5D (aka EuroQol 5D) 9. Health Utility Index HUI – 2 and 3 10. AQoL Class presentation in class 7 on national datasets. Students in pairs or individually select a national database (see table below) for secondary data analyses to review content and research results (10% of final grade) 1. National Committee for Quality Assurance Health Employers Data and Information Set (NCQA-HEDIS) 3. Longitudinal Studies of Aging 5. National Health Interview Survey 7. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) 9. NHANES 8. CDC Healthy Days 2. Minimal Data Set (MDS) for Nursing Homes 4. Outcome & Assessment Information Set (OASIS) for Home Health 6. American Community Survey 8. US Census 10. BRFSS Class presentation in class 12 on content of utility based HRQL questionnaires. (10% of final grade) RUBRIC FOR CLASS PRESENTATION Criterion (weight) Content (3.5) Assessment of Criterion (Note: Assigned score within a range is assessment of degree criterion is met.) Exceeds expectations (range 9.0-10.0) An abundance of material clearly related to thesis Points are clearly made and all evidence supports thesis Varied use of materials Meets expectations Below expectations (range 8.0-8.9) (range 7.0-7.9) Sufficient There is a great information that deal of information relates to thesis that is not clearly connected to the Many good points thesis made but there is an uneven balance and little variation Page 9 of 14 Not acceptable (range 0.0-6.9) Thesis not clear; information included that does not support thesis in any way Crit. Score Wt. Topic Points (= Crit. Score x Wt.) x3.5 = Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 RUBRIC FOR CLASS PRESENTATION Criterion (weight) Assessment of Criterion (Note: Assigned score within a range is assessment of degree criterion is met.) Exceeds expectations (range 9.0-10.0) Meets expectations Below expectations (range 8.0-8.9) (range 7.0-7.9) Not acceptable Creativity (1.5) Speaking Skills (2.0) Poised, clear articulation Proper volume Steady rate Good posture and eye contact; enthusiasm; confidence Length of Within one-two Presentation minutes of allotted time +/– Little or no variation Repetitive with little or no variety Material presented with little originality Insufficient use of or interpretation multimedia Clear articulation Some mumbling; but not as polished little eye contact Uneven rate Little or no expression Inaudible or too loud No eye contact Rate too slow/fast Speaker seemed uninterested and used monotone Within two-four minutes of allotted time +/– Too long or too short; ten or more minutes above or below the allotted time Within four-six minutes of allotted time +/– (0.5) Gross points for class presentation (maximum of 100) Topic Points (= Crit. Score x Wt.) Wt. (range 0.0-6.9) Thesis is clearly Most information Concept and ideas Presentation is stated and presented in logical are loosely choppy and developed sequence connected disjointed, does not flow Specific examples Generally very well Lacks clear are appropriate and organized but better transitions Development of Coherence clearly develop transitions from thesis is vague Flow and and thesis idea to idea needed organization are No apparent logical Organization Conclusion is clear; choppy order of shows control; flows presentation (2.5) together well Good transitions Succinct but not choppy Well organized Very original Some originality presentation of apparent material Good variety and Uses the blending of unexpected to full materials/media advantage Captures audience's attention Crit. Score x2.5 = x1.5 = x2.0 = x0.5 = ∑ Weight of class presentation in final grade (10%) x 0.10 Point contribution of class presentation to final grade (maximum of 10) = 4. Class exercises in SPSS and Excel. There are ten classes with these exercises; a student earns a point for each class for which the student hands in his or her exercise work in at the end of the class. (10% of final grade) 5. Final exam. The final exam consists of questions about a published article and is distributed in class 14. The final is a take-home exam and is due back within five days following class 14. (20% of final grade) Page 10 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 The following are intended to allow flexibility for busy students, while maintaining a sense of fairness to students who complete projects in a timely manner. Excused absences and assignment due dates All assignments must be completed and turned in on their assigned date and time. In the case of an excused absence from a class, arrangements with the course director must be made to submit the assignments for the class prior to the class or on an agreed-upon due date. Late assignments and penalties Assignments are considered late if turned in after 4:00 PM of the day following the assigned due date or other agreed-upon due date previously arranged with the instructor. Late assignments are penalized 10 points or 10 percentage-points, whichever is applicable, for each 24-hour delay. If an assignment is late by more than 48 hours, it is not accepted and receives a failing grade. Example: An assignment has an assigned due date of Thursday, October 5th. If it is turned in at 3:00 PM on Friday, October 6th, there is no penalty. If turned in at 5:00 PM on Friday, October 6th, the grade for the assignment is lowered 10 points or 10 percentage-points, whichever is applicable. If at 4:15 PM on Saturday, October 7th, the grade is lowered 20 points or 20 percentage-points, whichever is applicable. After 4:00 PM on Sunday, October 8th, the assignment receives a zero. Grading The components of student evaluation are weighted as follows: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Participation in classroom discussions Quizzes Class presentations Class exercises in SPSS and Excel Final exam 10% 30% 30% 10% 20% Grading is on letter scale basis. Final Grade A B C F Final Percent 90-100% 80-89% 70-79% ≤ 69% Page 11 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 Other Policies Syllabus Revision The course director reserves the right to modify any portion of this syllabus. A best effort is made to provide an opportunity for students to comment on a proposed change before the change takes place. Inclement Weather This course adheres to the University’s policy and decisions regarding cancellation or delayed class schedules. Adjustments are made to the class schedule as necessary to take into account any delays or cancellations of this class. Local television and radio stations broadcast University delays or closings. The UofL web site (www.louisville.edu) and telephone information line (502852-5555) also broadcast delays or closings. Grievances Students who have grievances regarding the course should contact the course director. Until a satisfactory resolution is reached, the matter is referred, in succession, to the chair of the course’s department, the Associate Dean for Students, and the School’s Student Academic Grievance Committee, and the University’s Student Academic Grievance Committee. Disabilities In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, students with bona fide disabilities are afforded reasonable accommodation. The Disability Resource Center certifies a disability and advises faculty members of reasonable accommodations. More information is located at http://www.louisville.edu/student/dev/drc/ Academic Honesty Students are required to comply with the academic honesty policies of the university and School of Public Health and Information Sciences. These policies prohibit plagiarism, cheating, and other violations of academic honesty. More information is located at https://docushare.louisville.edu/dsweb/Get/Document10846/SPHIS+Policy+on+Student+Academic+Honesty+Rev+3.pdf. Course instructors use a range of strategies (including plagiarism-prevention software provided by the university) to compare student works with private and public information resources in order to identify possible plagiarism and academic dishonesty. Comparisons of student works require students to submit electronic copies of their final works to the plagiarism-prevention service. The service delivers the works to instructors along with originality reports detailing the presence or lack of possible problems. The service retains copies of final works and may request students’ permission to share copies with other universities for the sole and limited purpose of plagiarism prevention and detection. Page 12 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research PHMS-702 In addition instructors provide the opportunity for students to submit preliminary drafts of their works to the service to receive reports of possible problems. Such reports are available only to the submitting student. Copies of preliminary drafts are not retained by the service. Additional Policy Information Consult the UofL Graduate Student Handbook for more about UofL policies. (http://graduate.louisville.edu/prog_pubs/handbook.pdf) Page 13 of 14 Methods in Health Services and Outcomes Research Course History Version: History: Data updated: 2009.07.08 v2009.07.08: Submitted 08/06/09. Approved 08/10/09. 08/12/09 Page 14 of 14 PHMS-702 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Required Reading List PHHS 702: Methods for Health Services and Outcomes Research SECTION I: Health Services and Outcomes Research Methods for Assessing Population Health Class 1: Introduction to Course: Definitions, Scope, Context and Constructs for Health Services and Outcomes Research Required Reading: Textbook: Wagner, Chapter 1: Overview pp 1-12 Kindig D. Stoddart G. What is population health? American Journal of Public Health. 93(3):3803, 2003 Mar. Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. International Journal of Epidemiology. 14(1):32-8, 1985 Mar. (A historic and classic article! – RWPS) Weiss AP. Measuring the impact of medical research: moving from outputs to outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry. 164(2):206-14, 2007 Feb. Ten Great Public Health Achievements -- United States, 1900-1999, MMWR April 02, 1999 / 48(12);241-243, accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/media/tengpha.htm on 08/08/08 Anonymous. Quality of care: 1. What is quality and how can it be measured? Health Services Research Group. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 146(12):2153-8, 1992 Jun 15. Guyatt G. Jaeschke R. Heddle N. Cook D. Shannon H. Walter S. Basic statistics for clinicians: 1. Hypothesis testing. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 152(1):27-32, 1995 Jan 1. Class 2: Basics of Mathematical Modeling Required Reading: Wagner, Chapter 2: Transforming Variables pp. 13 - 26 Handout: Kleinbaum, Epidemiologic Research Etches V. Frank J. Di Ruggiero E. Manuel D. Measuring population health: a review of indicators. Annual Review of Public Health. 27:29-55, 2006. Class 3: Basics of Mathematical Modeling – Part 2 Required Readin:g Textbook: Wagner, Chapter 3: Selecting Samples and Cases pp 27 -32 Gawande, Atul, The Cost Conundrum: What a Texas town can teach us about health care. New Yorker, June 1, 2009 accessed at http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/06/01/090601fa_fact_gawande on June 21, 2009. Hendryx MS. Beigel A. Doucette A. Introduction: risk-adjustment issues in mental health services. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 28(3):225-34, 2001 Aug. Page 1 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Fisher ES. Wennberg JE. Health care quality, geographic variations, and the challenge of supply-sensitive care. Perspectives in Biology & Medicine. 46(1):69-79, 2003. Wennberg JE. Practice variations and health care reform: connecting the dots. Health Affairs. Suppl Web Exclusive:VAR140-4, 2004. Guyatt G. Jaeschke R. Heddle N. Cook D. Shannon H. Walter S. Basic statistics for clinicians: 2. Interpreting study results: confidence intervals. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 152(2):169-73, 1995 Jan 15. Class 4: Introduction to Risk Adjustment as Confounding Recognizing confounding by comparing results Comparing OR in Crude and Adjusted Models Standard Million Method for Age Adjustment Required Readings: Zeni MB. Kogan MD. Existing population-based health databases: useful resources for nursing research. Nursing Outlook. 55(1):20-30, 2007 Jan-Feb. Iezzoni LI. Assessing quality using administrative data. Annals of Internal Medicine. 127(8 Pt 2):666-74, 1997 Oct 15. Pollack CD. Measuring health care outcomes with secondary data. Outcomes Management for Nursing Practice. 5(3):99-101, 2001 Jul-Sep. McGlynn EA. Asch SM. Adams J. Keesey J. Hicks J. DeCristofaro A. Kerr EA. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 348(26):2635-45, 2003 Jun 26. Anderson RN. Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. National Vital Statistics Reports. 47(3):1-16, 20, 1998 Oct 7. Class 5: Risk Adjustment: Social Gradient of Health: Race Class or Opportunity? Required Reading: Wagner, Chapter 6: Cross Tabs and Measures of Association pp 63 – 72 Marmot MG. Status syndrome: a challenge to medicine. JAMA. 295(11):1304-7, 2006 Mar 15. Marmot MG, Editorial: Creating healthier societies, Bull WHO 82:(5) 320, May 2004 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/bulletin/2004/Vol82-No5/bulletin_2004_82(5)_320.pdf Stansfeld SA. Bosma H. Hemingway H. Marmot MG. Psychosocial work characteristics and social support as predictors of SF-36 health functioning: the Whitehall II study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 60(3):247-55, 1998 May-Jun. Guyatt G. Walter S. Shannon H. Cook D. Jaeschke R. Heddle N. Basic statistics for clinicians: 4. Correlation and regression. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 152(4):497-504, 1995 Feb 15. Page 2 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Class 6: Student Presentations about Measures for Risk Adjustment Selecting Indicators and Reporting Results for Health Report Cards; Measures of Frequency, Association and Impact; Do we need CI(95) in enumerated measures? Impairment, Disability, Handicap in Health Status Assessment and HRQL Required Reading: Wagner, Chapter 5: Charts and Graphs pp 43 - 62 Singh-Manoux A. Nabi H. Shipley M. Gueguen A. Sabia S. Dugravot A. Marmot M. Kivimaki M. The role of conventional risk factors in explaining social inequalities in coronary heart disease: the relative and absolute approaches to risk. Epidemiology. 19(4):599-605, 2008 Jul. Jette AM. Keysor JJ. Uses of evidence in disability outcomes and effectiveness research. Milbank Quarterly. 80(2):325-45, 2002. Grotle M. Brox JI. Vollestad NK. Functional status and disability questionnaires: what do they assess? A systematic review of back-specific outcome questionnaires. Spine. 30(1):130-40, 2005 Jan 1. Andresen EM. Vahle VJ. Lollar D. Proxy reliability: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measures for people with disability. Quality of Life Research. 10(7):609-19, 2001. Class 7: Sources of Data; Primary and Secondary Analyses Required Readings: Wagner, Chapter 4: Organization and Presentation of Information pp. 33 – 42 Tang PC. Ralston M. Arrigotti MF. Qureshi L. Graham J. Comparison of methodologies for calculating quality measures based on administrative data versus clinical data from an electronic health record system: implications for performance measures. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 14(1):10-5, 2007 Jan-Feb. Pollack CD. Methodological considerations with secondary analyses. Outcomes Management for Nursing Practice. 3(4):147-52, 1999 Oct-Dec. 2000 Health Status Report Card for Jefferson County, Kentucky (public record; Handout). Class 8: Vital Statistics: Birth and Death Certificates Examining the Exposure-Disease (E-D) Associations in Public Health Quality of Data for Outcomes in PH: Accuracy of Recorded Cause of Death on Death Certificates: Autopsy as Gold Standard Required Readings: Wagner, Chapter 7: Correlation and Regression pp. 73 – 82 Page 3 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Modelmog D. Rahlenbeck S. Trichopoulos D. Accuracy of death certificates: a populationbased, complete-coverage, one-year autopsy study in East Germany. Cancer Causes & Control. 3(6):541-6, 1992 Nov. Roulson J. Benbow EW. Hasleton PS. Discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnosis and the value of post mortem histology; a meta-analysis and review. Histopathology. 47(6):551-9, 2005 Dec. Completing Death Certificates http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/misc/hb_cod.pdf , esp. pp 7 – 33. Parts of quiz will come from case examples of death certificate in this section. Death certificate available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nmfs/nmfs.htm Class 9: Benefits of the Birth Cohort Method for Estimating Infant Mortality Quality of Data for Accuracy of Exposure Status: Maternal Reports about Prenatal Smoking Required Readings: Validity/Accuracy of Public Health Data: Prenatal Maternal Tobacco Smoking Examining Information Bias within An Exposure Variable Wagner, Chapter 9: ANOVA pp. 95 - 100 Webb DA. Boyd NR. Messina D. Windsor RA. The discrepancy between self-reported smoking status and urine cotinine levels among women enrolled in prenatal care at four publicly funded clinical sites. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice. 9(4):322-5, 2003 Jul-Aug. Dietz PM. Adams MM. Kendrick JS. Mathis MP. Completeness of ascertainment of prenatal smoking using birth certificates and confidential questionnaires: variations by maternal attributes and infant birth weight. PRAMS Working Group. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. American Journal of Epidemiology. 148(11):1048-54, 1998 Dec 1. Birth certificate form (handout or online…) McGinn T. Wyer PC. Newman TB. Keitz S. Leipzig R. For GG. Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working Group. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 3. Measures of observer variability (kappa statistic). CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171(11):1369-73, 2004 Nov 23. Tooth LR. Ottenbacher KJ. The kappa statistic in rehabilitation research: an examination. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 85(8):1371-6, 2004 Aug. Class 10: Systematic Reviews, Developing Clinical Guidelines Required Readings: Cronin P. Ryan F. Coughlan M. Undertaking a literature review: a step-by-step approach. British Journal of Nursing. 17(1):38-43, 2008 Jan 10-23. Harris RP. Helfand M. Woolf SH. Lohr KN. Mulrow CD. Teutsch SM. Atkins D. Methods Work Group, Third US Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the US Page 4 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 20(3 Suppl):21-35, 2001 Apr. Barton MB. Miller T. Wolff T. Petitti D. LeFevre M. Sawaya G. Yawn B. Guirguis-Blake J. Calonge N. Harris R. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. How to read the new recommendation statement: methods update from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 147(2):123-7, 2007 Jul 17. Sawaya GF. Guirguis-Blake J. LeFevre M. Harris R. Petitti D. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Update on the methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: estimating certainty and magnitude of net benefit. Annals of Internal Medicine. 147(12):871-5, 2007 Dec 18. Class 11: Psychometrics: Measures of Validity and Reliability - Measuring Depression Prevalence of Disease Influences the Results of Screening; Serial Screening; Adjusting for Depression Comparing Outcomes for Measures for Depression (CESD, PHQ, etc.) Improving Accuracy of Questionnaires with Serial Testing Required Readings: Thibault, JM. Steiner RWP, Efficient Identification of Adults with Depression and Dementia. Am Fam Physician 2004;70:1101-10. Accessed at http://www.aafp.org/afp/20040915/1101.html accessed on August 7, 2008. Lowe B. Kroenke K. Grafe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2). Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 58(2):163-71, 2005 Feb. Cannon DS. Tiffany ST. Coon H. Scholand MB. McMahon WM. Leppert MF. The PHQ-9 as a brief assessment of lifetime major depression. Psychological Assessment. 19(2):247-51, 2007 Jun. Pignone MP. Gaynes BN. Rushton JL. Burchell CM. Orleans CT. Mulrow CD. Lohr KN. Screening for depression in adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Internal Medicine. 136(10):765-76, 2002 May 21. See PHQ- 9 http://muskie.usm.maine.edu/clinicalfusion/DHHS/phq9.pdf Montori VM. Wyer P. Newman TB. Keitz S. Guyatt G. Evidence-Based Medicine Teaching Tips Working Group. Tips for learners of evidence-based medicine: 5. The effect of spectrum of disease on the performance of diagnostic tests. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 173(4):385-90, 2005 Aug 16. Class 12: HRQL and Content Validity: Same Name – Different Items: Examining Content of Quality of Life Questionnaires in Outcomes Research: Making a Case for Measures of Positive Health Required Readings: Wagner, Chapter 11: Advanced Applications pp. 109 - 114 Page 5 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Guyatt, Gordon H. Feeny, David H. Patrick, Donald L. Measuring Health-related Quality of Life. Annals of Internal Medicine. 118(8):622-629, April 15, 1993. (NOTE: Quality of Life assessments are the beginning and endpoint for policy development in PRECEDE-PROCEED model.) Frost MH. Sloan JA. Quality of life measurements: a soft outcome--or is it? American Journal of Managed Care. 8(18 Suppl):S574-9, 2002 DecHanita M. Self-report measures of patient utility: should we trust them? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 53(5):469-76, 2000 May. Anonymous. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Quality of Life Research. 11(3):193-205, 2002 May. Coons SJ. Rao S. Keininger DL. Hays RD. A comparative review of generic quality-of-life instruments. Pharmacoeconomics. 17(1):13-35, 2000 Jan. Class 13: Change scores with standardized HRQL Questionnaires : Within person Responsiveness, Meaningful Differences Required Readings: Revicki D. Hays RD. Cella D. Sloan J. Recommended methods for determining responsiveness and minimally important differences for patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 61(2):102-9, 2008 Feb. Wiebe S. Guyatt G. Weaver B. Matijevic S. Sidwell C. Comparative responsiveness of generic and specific quality-of-life instruments. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 56(1):5260, 2003 Jan. Schwartz CE. Andresen EM. Nosek MA. Krahn GL. RRTC Expert Panel on Health Status Measurement. Response shift theory: important implications for measuring quality of life in people with disability. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 88(4):529-36, 2007 Apr. Class 14: Quality of Care: Managing Change for Quality Improvement Initiatives; From Benchmarking to Policy Implementation, to Institutionalization and Cultural Adaptations Required Readings: Westfall JM. Mold J. Fagnan L. Practice-based research --"Blue Highways" on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 297(4):403-6, 2007 Jan 24. Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA 2008;299:211-3. Dougherty D, Conway PH. The “3T's” road map to transform US health care: the “how” of high-quality care. JAMA 2008;299:2319-21. Fisher ES. Pay for Performance – Risks and Recommendations, NEJM 355:18, 1845-47. Hofer TP. Hayward RA. Greenfield S. Wagner EH. Kaplan SH. Manning WG. The unreliability of individual physician "report cards" for assessing the costs and quality of care of a chronic disease. JAMA. 281(22):2098-105, 1999 Jun 9. Page 6 Attachment 1: Sample of Required Reading List Davis DA. Mazmanian PE. Fordis M. Van Harrison R. Thorpe KE. Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 296(9):1094-102, 2006 Sep 6. Cabana MD. Rand CS. Powe NR. Wu AW. Wilson MH. Abboud PA. Rubin HR. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 282(15):1458-65, 1999 Oct 20. Page 7 Attachment 2: Sample of Suggested Reading List Suggested Reading List PHHS 702: Methods for Health Services and Outcomes Research GENERAL Suggested Reading (for students with specific interests): McDowell, Ian. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires, 3rd Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. This is a gold standard reference for assessing content and psychometric properties of healthrelated questionnaires for research. It deals with issues of which questionnaires might be used for a given research project. This is an expensive text, but worthwhile for students interested in measurement. NOTE: On reserve in HSC Kornhauser Library Iezzoni, Lisa I (Ed.). Risk Adjustment for Measuring Health Care Outcomes, 3rd Edition. Chicago Ill: Health Administration Press, 2003. This text is the most readable book about the technical aspects of health services and outcomes research methods that the course director has found to date. It deals with issues of how one might conduct the HSR research design and analysis processes. Probably too advanced for most students at this entry-level course. Devellis, R. F. Scale Development: Theory and applications, 2nd Edition. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2003. Good reference for details on psychometrics. NOTE: On reserve in HSC Kornhauser Library Cramer JA., Spilker B. Quality of Life and Pharmaco-Economics: An Introduction. Lippincott – Raven, Philadelphia, 1998. This is a good reference for quality of life assessment and is very inexpensive when purchased used, e.g., from the “used section” in Amazon.com. Fayers R and Hays RD. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials: Methods and Practice, 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, USA, 2005. SECTION I: Health Services and Outcomes Research Methods for Assessing Population Health Class 1: Introduction to Course: Definitions, Scope, Context and Constructs for Health Services and Outcomes Research Suggested Reading Executive Summary, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. National Academic Press, Washington DC 2001. Available as pdf. file at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=9728 Executive Summary, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, National Academic Press, Washington DC 2001. Available as pdf. file at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=10027 Class 2: Basics of Mathematical Modeling Page 1 Attachment 2: Sample of Suggested Reading List Class 3: Basics of Mathematical Modeling – Part 2 Suggested Reading and Viewing The State of the Nation's Health, accessed at http://dartmed.dartmouth.edu/spring07/html/atlas.php on August 7, 2008. Online Viewing See John Wennberg’s short online videos – less than 20 minutes! http://dartmed.dartmouth.edu/spring07/html/atlas_we.php http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/ http://dartmed.dartmouth.edu/spring07/html/features.php Class 4: Introduction to Risk Adjustment as Confounding Recognizing confounding by comparing results Comparing OR in Crude and Adjusted Models Standard Million Method for Age Adjustment Suggested Reading: Fries JF. Compression of morbidity in the elderly. Vaccine. 18(16):1584-9, 2000 Feb 25. Klein RJ, Schoenborn CA. Age adjustment using the 2000 projected U.S. population. Healthy People Statistical Notes, no. 20. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics. January 2001. accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/datawh/nchsdefs/ageadjustment.htm on August 29, 2008; Also see About Age Adjusted Rates, 95% Confidence Intervals And Unstable Rates, Department of Health, Information for a Healthy New York, March 2006 accessed at http://www.health.state.ny.us/statistics/cancer/registry/age.htm on July 8, 2009. Class 5: Risk Adjustment: Social Gradient of Health: Race Class or Opportunity? Suggested Readings: Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Marmot MG. Smith GD. Stansfeld S. Patel C. North F. Head J. White I. Brunner E. Feeney A. Lancet. 337(8754):1387-93, 1991 Jun 8. Ferrie JE. Shipley MJ. Davey Smith G. Stansfeld SA. Marmot MG. Change in health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 56(12):922-6, 2002 Dec. Kuzel AJ. Naturalistic inquiry: an appropriate model for family medicine. 1986. Family Medicine. 30(9):665-71, 1998 Oct. Suchman AL. A new theoretical foundation for relationship-centered care. Complex responsive processes of relating. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 21 Suppl 1:S40-4, 2006 Jan. Kleinman A. Eisenberg L. Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Annals of Internal Medicine. 88(2):251-8, 1978 Feb. Class 6: Student Presentations about Measures for Risk Adjustment Page 2 Attachment 2: Sample of Suggested Reading List Selecting Indicators and Reporting Results for Health Report Cards; Measures of Frequency, Association and Impact; Do we need CI(95) in enumerated measures? Impairment, Disability, Handicap in Health Status Assessment and HRQL Suggested Reading: Zambroski CH. Qualitative analysis of living with heart failure. Heart & Lung. 32(1):32-40, 2003 Jan-Feb. Verbrugge LM. Patrick DL. Seven chronic conditions: their impact on US adults' activity levels and use of medical services. American Journal of Public Health. 85(2):173-82, 1995 Feb. Class 7: Sources of Data; Primary and Secondary Analyses Suggested Reading: Ron Crouch, MSSW Director Ky. State Data Center United States and Kentucky Trends (pdf) and World, United States and Kentucky Trends, both available at http://ksdc.louisville.edu/1presentations.htm , accessed December 14, 2007. Class 8: Vital Statistics: Birth and Death Certificates Examining the Exposure-Disease (E-D) Associations in Public Health Quality of Data for Outcomes in PH: Accuracy of Recorded Cause of Death on Death Certificates: Autopsy as Gold Standard Suggested Reading: Ostbye T. Taylor DH Jr. Clipp EC. Scoyoc LV. Plassman BL. Identification of dementia: agreement among national survey data, medicare claims, and death certificates. Health Services Research. 43(1 Pt 1):313-26, 2008 Feb. Hopkins DD. Grant-Worley JA. Bollinger TL. Survey of cause-of-death query criteria used by state vital statistics programs in the US and the efficacy of the criteria used by the Oregon Vital Statistics Program. American Journal of Public Health. 79(5):570-4, 1989 May. Bethell CD. Read D. Brockwood K. American Academy of Pediatrics. Using existing population-based data sets to measure the American Academy of Pediatrics definition of medical home for all children and children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 113(5 Suppl):1529-37, 2004 May. Class 9: Benefits of the Birth Cohort Method for Estimating Infant Mortality Quality of Data for Accuracy of Exposure Status: Maternal Reports about Prenatal Smoking Page 3 Attachment 2: Sample of Suggested Reading List Class 10: Systematic Reviews, Developing Clinical Guidelines Suggested Reading: (New text): Institute of Medicine, Knowing What Works in Health Care: A Roadmap for the Nation, National Academic Press, 2008. [Looks like the best book reading yet on systematic reviews & clinical practice guidelines! RWPS] Calonge N. Randhawa G. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. The meaning of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force grade I recommendation: screening for hepatitis C virus infection. Annals of Internal Medicine. 141(9):718-9, 2004 Nov 2. Guirguis-Blake J. Calonge N. Miller T. Siu A. Teutsch S. Whitlock E. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current processes of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: refining evidence-based recommendation development. Annals of Internal Medicine. 147(2):117-22, 2007 Jul 17. Moher D. Altman DG. Schulz KF. Elbourne DR. Opportunities and challenges for improving the quality of reporting clinical research: CONSORT and beyond. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 171(4):349-50, 2004 Aug 17. Guyatt GH. Oxman AD. Vist GE. Kunz R. Falck-Ytter Y. Alonso-Coello P. Schunemann HJ. GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 336(7650):924-6, 2008 Apr 26. Ebell MH. Siwek J. Weiss BD. Woolf SH. Susman J. Ewigman B. Bowman M. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 17(1):59-67, 2004 Jan-Feb. Class 11: Psychometrics: Measures of Validity and Reliability - Measuring Depression Prevalence of Disease Influences the Results of Screening; Serial Screening; Adjusting for Depression Comparing Outcomes for Measures for Depression (CESD, PHQ, etc.) Improving Accuracy of Questionnaires with Serial Testing Suggested Reading: See USPSTF http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/depression/depressrr.htm Devellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications (2nd Edition). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. pp. ___ (section on Reliability Coefficients). Nease DE Jr. Maloin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Pract. 2003 Feb;52(2):118-24 available through PubMed at http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=1387 accessed on August 7, 2008. Class 12: HRQL and Content Validity: Same Name – Different Items: Examining Content of Quality of Life Questionnaires in Outcomes Research: Making a Case for Measures of Positive Health Page 4 Attachment 2: Sample of Suggested Reading List Class 13: Change scores with standardized HRQL Questionnaires : Within person Responsiveness, Meaningful Differences Suggested Reading: Guyatt GH. Osoba D. Wu AW. Wyrwich KW. Norman GR. Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 77(4):371-83, 2002 Apr. Wyrwich KW. Tierney WM. Babu AN. Kroenke K. Wolinsky FD. A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease. Health Services Research. 40(2):577-91, 2005 Apr. Wyrwich KW. Bullinger M. Aaronson N. Hays RD. Patrick DL. Symonds T. The Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Quality of Life Research. 14(2):285-95, 2005 Mar. Wyrwich KW. Tierney WM. Wolinsky FD. Using the standard error of measurement to identify important changes on the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Quality of Life Research. Class 14: Quality of Care: Managing Change for Quality Improvement Initiatives; From Benchmarking to Policy Implementation, to Institutionalization and Cultural Adaptations Suggested Reading: Naik, AD, Petersen LA. The Neglected Purpose of Comparative-Effectiveness Research. New England Journal of Medicine. 360(19):1929-1931, May 7, 2009. Woolf SH. Patient safety is not enough: targeting quality improvements to optimize the health of the population. Annals of Internal Medicine. 140(1):33-6, 2004 Jan 6. Bodenheimer T. Interventions to improve chronic illness care: evaluating their effectiveness. Disease Management. 6(2):63-71, 2003. Petersen LA. Woodard LD. Urech T. Daw C. Sookanan S. Does pay-for-performance improve the quality of health care? Annals of Internal Medicine. 145(4):265-72, 2006 Aug 15. McDonald, Ruth, Roland, Martin. Pay for Performance in Primary Care in England and California: Comparison of Unintended Consequences, Ann Fam Med 2009 7: 121-127 Page 5