Paper at UNESCO Virtual Congress, October

advertisement

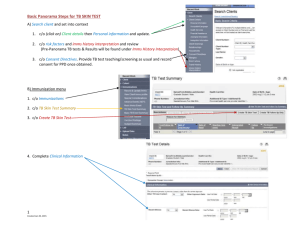

Immersive photographic panoramas of Cultural Heritage 1873-2002 in dynamic viewers on-line (Internet & CD media project) Dariusz CZARNIAWSKI1, Jacek GANCARSON2, Grzegorz KARYKOWSKI1, Thomas MAJCHRZAK, Kazimierz STACHURSKI4 1 City of Warsaw Promotional Department, POLAND 2 Eurofresh, Stockholm, SWEDEN 3 National Museum ín Warsaw, POLAND ABSTRACT The tradition of taking a circular series of photos from a single focal point, in order to show broad views, originated in the mid19th century. These sets of photographs were often joined together into a single panoramic image. Although they precisely document the surrounding view, spatial understanding of the landscape, angular locations of objects in the field of view, and mutual distances between these objects are difficult to perceive and compare. This is obvious if we recall the fact that our immediate visual recognition of surrounding space is determined by an ocular, sequential scan (by turning our head around), with an active field of view limited to approx. 90 degrees. Therefore, it is much easier to acquire spatial information when playing a video clip which was recorded moving around the vertical axis on a tripod, or when scanning a panorama leftward-rightward through an observation window (see Figure 1), than to acquire spatial information encompassed by a very broad panorama, pieced together from a series of photos and printed on paper, or by a very broad panoramic painting on a large canvas. For such panoramas it became natural to present them on surfaces surrounding the visitors. The next step toward facilitation of perception is displaying the panorama interactively on a computer screen (see Figure 2) with the help of suitable viewer-software, such as a Java applet for low resolution panoramas, or Quick Time plugin for high resolution panoramas. These viewers allow infinite rotation in both horizontal directions, zooming in and upward and downward tilting within the vertical boundaries of the panorama. Such a tool makes the whole perception process more intuitive and efficient, especially in the case of very wide, or circular (360 degree), panoramic photographs. The mapping process in our mind here is quite similar to what we use in the real environment. In this way we can learn more from old panoramas than our predecessors, who had to take in entire panoramas at a single glance. ----------------------- Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. UNESCO Virtual Congress, October-November 2002. © 2002 UNESCO WHC 1-00000-000-0/00/0000…$5.00. Figure 1. Linear presentation of a surround panorama (old panoramic photographs on paper or a large canvas, rectangular images on a computer screen). Figure 2. Infinite rotating presentation of a circular surround panorama (circular room or panorama viewer on a computer screen). However, the level of interest in the technical issues of projecting immersive panoramas on the web depends on the degree to which a given business depends on its web interface in general, and on visualisation techniques in particular. Use of immersive panoramas as a natural extension of traditional photographs is still not obvious. One reason may be uncertainty due to the legal controversy over proprietary inventions [Oxaal 1993] encountered in daily practice by individual photographers world-wide. The second reason may be the growing diversification of Internet technology as a result of its commercialisation. It is more difficult to optimise the presentation so that panoramas will be rapidly accessible to all web visitors. Not being fully convinced that access to immersive panoramas by their Internet customers is secure, some web content editors avoid using them. In our Internet project, a Virtual Tour through Warsaw Old Town – UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage site No. 30, we decided to design and configure a Remote Observation Panel [Gancarson, 2001], basing on a highly configurable Java viewer [Dersch, 1998]. It provides a secure Internet presentation of a virtual tour on most OSs. The tour contains 35 immersive panoramas from Warsaw’s Old Town. The panel is launched in a pop-up window, in front of descriptive text about the Cultural Heritage site (see Figure 3). them two surround panoramas, from an Internet directory of old panoramic photographs at the Library of Congress. They have undergone basic retouching in order to reduce optical noise. Due to the low resolution, a Java viewer was chosen. In similar way, a circular panorama of Warsaw, dated from 1873 and archived at the National Museum in Warsaw, was first displayed with this technique in August 2002, using both a PTviewer and Quick Time plugin. Web resolution examples are available at the url: www.eurofresh.se/history/ and on CD. Keywords: Panoramic photography, immersive imaging, online visualisation, cultural heritage online, perception extension, old photography, history, historical photography, photographic panorama, educational tool. REFERENCES GANCARSON, J., Virtual Tour through the Old Town, Historical Centre of Warsaw, World Heritage site No. 30, in a Remote Observation Panel: http://www.eurofresh.se/warsaw/index-wh30.htm http://archiwum.warszawa.um.gov.pl/test/foto/ DERSCH. H., PtViewer, http://www.fh-furtwangen.de/~dersch/ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, Panoramic Photographs, http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/pnhtml/pnhome.html OXAAL, F., Pictosphere background: http://www.pictosphere.com/picto-background.html Figure 3. Web view of the panorama panel. The text may be read while waiting for the panoramas to download. The pop-up window’s canvas area is used in full. An interactive map showing all panoramas locations and a dynamic pointer indicating viewing direction are adjacent to the panorama viewer. The map’s compass orientation is also shown. Pointers are activated individually for each panorama displayed. Visitors can launch a particular panorama in 3 ways: (a) from the map, (b) from the list, or (c) by exploration of transient hotspots on subsequent panoramas. The internal control panel contains buttons to pan in four directions, a stop button, a reset button for fast levelling of the field of view, zoom-in and zoom-out buttons and an information button. Panoramas are stored in JPG format with a volume of 120-200 Kbytes each. As the panel contains 35 spherical panoramas in small files, a map and compass, the use of multiple files and a Java PTviewer is the most effective on the web in the current state of technology, as other web formats still do not provide all the features required. Old panoramas were also presented on the Internet in a pilot project of 2001. With the use of Flash, Quick Time and Java applets, we converted and displayed seven panoramas, among ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dariusz Czarniawski, officer in charge, City of Warsaw Promotional Department, Poland. Email: darek@czerniawski.bydg.pl Jacek Gancarson is a web developer, Director of Eurofresh, Stockholm, Sweden. He can be contacted at: Eurofresh, Hauptvägen 101, 12358 Farsta, SWEDEN. Email: jacek.gancarson@eurofresh.se Grzegorz Karykowski, Webmaster City of Warsaw Promotional Department, POLAND. Email: gkarykowski@warszawa.um.gov.pl Thomas Majchrzak, Programmer, Echeloh. 39, 44149 Dortmund, GERMANY. Email: thomas@musik-pegasus.de Dr Kazimierz Stachurski is Exhibitions and Marketing Director of the National Museum in Warsaw, POLAND. He can be contacted at: National Museum Warsaw, Al. Jerozolimskie 3, 00495 Warsaw, POLAND. Email: kstachurski@mnw.art.pl