Teaching in – and about – a Crossroads of Civilizations: Reflections

advertisement

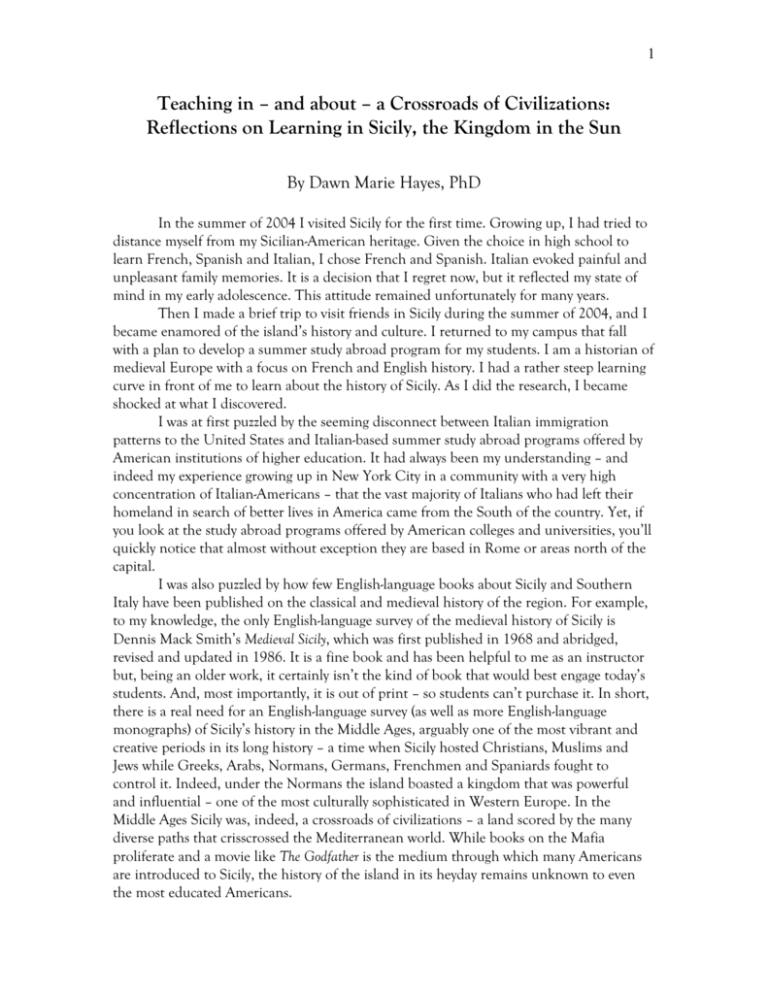

1 Teaching in – and about – a Crossroads of Civilizations: Reflections on Learning in Sicily, the Kingdom in the Sun By Dawn Marie Hayes, PhD In the summer of 2004 I visited Sicily for the first time. Growing up, I had tried to distance myself from my Sicilian-American heritage. Given the choice in high school to learn French, Spanish and Italian, I chose French and Spanish. Italian evoked painful and unpleasant family memories. It is a decision that I regret now, but it reflected my state of mind in my early adolescence. This attitude remained unfortunately for many years. Then I made a brief trip to visit friends in Sicily during the summer of 2004, and I became enamored of the island’s history and culture. I returned to my campus that fall with a plan to develop a summer study abroad program for my students. I am a historian of medieval Europe with a focus on French and English history. I had a rather steep learning curve in front of me to learn about the history of Sicily. As I did the research, I became shocked at what I discovered. I was at first puzzled by the seeming disconnect between Italian immigration patterns to the United States and Italian-based summer study abroad programs offered by American institutions of higher education. It had always been my understanding – and indeed my experience growing up in New York City in a community with a very high concentration of Italian-Americans – that the vast majority of Italians who had left their homeland in search of better lives in America came from the South of the country. Yet, if you look at the study abroad programs offered by American colleges and universities, you’ll quickly notice that almost without exception they are based in Rome or areas north of the capital. I was also puzzled by how few English-language books about Sicily and Southern Italy have been published on the classical and medieval history of the region. For example, to my knowledge, the only English-language survey of the medieval history of Sicily is Dennis Mack Smith’s Medieval Sicily, which was first published in 1968 and abridged, revised and updated in 1986. It is a fine book and has been helpful to me as an instructor but, being an older work, it certainly isn’t the kind of book that would best engage today’s students. And, most importantly, it is out of print – so students can’t purchase it. In short, there is a real need for an English-language survey (as well as more English-language monographs) of Sicily’s history in the Middle Ages, arguably one of the most vibrant and creative periods in its long history – a time when Sicily hosted Christians, Muslims and Jews while Greeks, Arabs, Normans, Germans, Frenchmen and Spaniards fought to control it. Indeed, under the Normans the island boasted a kingdom that was powerful and influential – one of the most culturally sophisticated in Western Europe. In the Middle Ages Sicily was, indeed, a crossroads of civilizations – a land scored by the many diverse paths that crisscrossed the Mediterranean world. While books on the Mafia proliferate and a movie like The Godfather is the medium through which many Americans are introduced to Sicily, the history of the island in its heyday remains unknown to even the most educated Americans. 2 I encountered several challenges in organizing the program. The most serious was finding an institution that could provide classroom space and housing. Because Sicily is off the beaten path, there is not available the developed infrastructure that you can find in the North. [IMAGE] Thankfully, my university has been able to partner with Babilonia and the hard work we’ve done together has produced a wonderful program in which students stay in a 2-star pensione. But it does take an extra effort to set up a program in an area less traveled. Related to this is the higher airfare associated with travel to Sicily. Since we are not able to fly directly to a major hub, the airfare is higher. The added cost for the hotel stay, combined with a higher airfare, makes for a slightly higher overall program cost. And this is a challenge the program has labored against during the first two years of its life. MSU’s summer program in northern Italy was on average $600 less than the cost of this year’s Sicily program, and this added financial burden can play an important role in the decisions students make when thinking about studying abroad. The program, whose formal name is the Montclair State University’s International Summer Institute in Sicily, is based in Taormina [IMAGE], a beautiful town that in spite of seismic and volcanic activity all around it has remained relatively untouched. The town itself is a teaching tool because it retains its medieval feel and challenges my students, who come from the sprawling suburbs of New Jersey, to think about space differently while impressing upon them the age of island and its long history. As the historical focal point of the town the Teatro Greco [IMAGE], which is more appropriately termed the Teatro Antico since Greeks and Romans have left their mark on the structure, teaches a number of important lessons. It demonstrates to them first-hand the capabilities of ancient societies that did not have access to modern technology. It also teaches them about Greek aesthetics and how ancient people tried to incorporate nature into their building projects. Seeing Mt. Etna [IMAGE] in the distance is a powerful visual and offers a wonderful example of how the ancient Greeks exploited nature in their artistic expressions. Yet the changes the Romans made to the theater, adding a temporary ceiling and walls that blocked the surrounding views, give students a sense of the different aesthetics of these related cultures. Those students who have chosen to attend performances in the Teatro Greco have had the added benefit of viewing for themselves artistic performances in a theater built by the ancients. This, of course, is an experience that cannot be replicated here in the States. Other lessons about classical civilization are experienced during a field trip to Agrigento and the town of Piazza Armerina. At the former [IMAGE], students see the remains of the great Greek-style temples and get a sense of the wealth that circulated in some areas of Sicily during the age of the tyrants. Only Athens itself built more temples than Agrigento in the fifth century BC, a distinction that might have been made possible by the town’s wine and olive exports to Carthage, which would today be located in Tunisia. The Villa at Piazza Armerina [IMAGE] also provides a powerful example of the wealth that at times circulated in Sicily which, incidentally, was the first province of the Roman Republic. With over 50 rooms and a dazzling array of mosaics intact, the villa itself impresses upon students the building capabilities of the Romans while the mosaics show the various kinds of animal life – as well as scenes from mythology – which make these distant civilizations seem much more real. One student from this summer’s program wrote: 3 Piazza Armerina was by far the most beautiful sight I have ever seen. I was quite impressed that most of the mosaics were well preserved . . . . Each room was filled with vibrant mosaics, which sparked in me a new interest for Roman art and culture. I particularly enjoyed the hallway, which our guide pointed out represented people and animals from both East and West. From what I can recall, the guide stated that this hallway represented “The Great Hunt”, in which animals from all over were brought back to Rome. I remember this mosaic being particularly breathtaking because it was well preserved and because it depicts a variety of animals. The intention of this mosaic was to show all animals that were captured throughout the empire. The rich mix of cultures that is the main organizing principle of the course I teach, “Kingdoms in the Sun: Southern Italy and Sicily in Antiquity and the Middle Ages” is again underscored in a day-long field trip to Palermo and Monreale. In the capital they visit a number of sites. The visit to the Palatine Chapel [IMAGE], a 12th-century structure built by Roger II within the Norman Palace, emphasizes the importance of religion in this society while introducing students to the complexity of the culture. Students have been intrigued by the idea that Muslim craftsmen had worked on the chapel, leaving distinctive evidence of their own culture in this Christian sanctuary [IMAGE]. Yet they see even more obvious Arabic influence on Norman architecture at La Zisa [IMAGE], a Norman pleasure palace completed in the 12th century. For example, the palace’s muqarnas (stalactite vaults) [IMAGE] reveal the strong influence Arabic art and architecture had on Norman Sicily. The Arabesque domes that sit at the top of the Monastery of St. John of the Hermits [IMAGE] also underscore the cultural fusion of Arabic elements that was achieved under the Norman rulers of Sicily. While the visit to the Palatine Chapel demonstrates the importance of Muslim artists in the Kingdom in the Sun, it also introduces students to another important cultural influence in medieval Sicily: the Byzantine Empire. The use of golden mosaics as an art form is most closely associated with this culture, and the frequent iconographic portrayal of human forms and of Jesus Christ in Norman structures, echoes trends on the southern Italian mainland as well as in Byzantium itself. Past students have been struck by two famous Norman mosaics in the church of La Martorana, another twelfth-century structure. One shows Roger II [IMAGE], looking very imperial in Byzantine-style garb, receiving his crown directly from Christ himself, a powerful statement about the source of the king’s power. Furthermore, not only is Roger crowned by Christ – he even looks like Him. Notice the similarity in facial features and hair, with both men cutting very iconic images complete with elongated noses. Completing the Byzantine influence are the Greek letters that indicate that you are looking at Roger the King and Christ. The other icon displays an image of George of Antioch [IMAGE], the church’s founder, presenting the sanctuary as a gift to the Virgin Mary. Although George resembles a turtle, the Virgin (referred to here as Mary, the Theotokos or Christ-bearer) is striking in Byzantine garb. A visit later in the day to Monreale [IMAGES OF EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR], regal in its use of mosaics and multicultural in its use of Greek and Latin alphabets, emphasizes the point. These trips – along with the lectures and readings that are assigned as part of the course – introduce Sicilian (and to a lesser degree southern Italian) history to students who almost without exception have no prior knowledge of the island’s past. Classics major who 4 participated in the 2006 program remarked that, in American schools, Sicily is only mentioned in pre-modern historical narratives at the point of the Punic Wars. Other than that, the island’s distant past is hardly ever mentioned. I suspect that to a great extent she is right. This is a shame and it is the mission of MSU’s summer institute in Sicily to help change American academic neglect of the island. And I think it can be done. The combination of Sicily’s staggering natural beauty, combined with an exciting multi-layered historical narrative, can combine to create a wonderful laboratory for learning. A journal entry written by a student the night before she was returning to the States reflects what, ideally, can be achieved through the programs that are the subject of this panel: I had always wondered why my Sicilian friends insisted on being called Sicilian rather than Italian. Now I understand. Upon my arrival here, I became immediately aware of the island's richness and diversity in culture. To be Sicilian is to be unique. The island could be its own country because of its difference in comparison to the mainland. I doubt there is another place quite like Sicily in the world. Each culture left its own mark whether separately or by building on previous ideas and structures so that you end up with a conglomeration like sedimentary layers of rock. Each layer is a discovery of treasure that describes the period in which it was created. Each people brought its own art, laws and social systems. However, we could say that on this island, the Greeks are known for having brought art and drama; the Romans organized the cities and instituted a legal system; the Byzantines brought with them Christianity and produced incredible religious art; and the Muslims added to the variety of structures here with their mosques and other buildings, as well as adding to the knowledge and systems in literature, religion, law, arts, sciences, math and philosophy. Of the Normans, we find their additions to the existing structures and can attribute to them the unity of the Catholic religion on this island and the beginnings of the language change to Italian. How does one describe Sicily in just a few words? Last night as I watched the swallows swoop and soar over the vision of the sea framed by a backdrop of the misty mountains of mainland Italy, I was filled with a bittersweet feeling -- joy for this experience but sadness over its inevitable end. The strongest of my emotions right now is deep gratitude for being able to experience a place like no other in the world. I am not of Sicilian descent. I came here because I wanted to know the land and the people and because I wanted to study history in its pure form. Sicily is as rich in natural color as it is in history. It is one island but it holds a universe of culture and beauty. I think this is a wonderful reaction piece – one rich in learning and insight made possible, at least in part, by the opportunity to study Sicilian history and culture in context. And this brings me to my last thought. Research on pedagogy has suggested that students learn deeply when they are forced to abandon known models and exchange them for new ones. Therefore, the very act of studying abroad – of abandoning what is comfortable and grappling instead with new and unfamiliar languages, customs, foods, terrain, etc. primes students for deep learning – learning that will transform them and affect the trajectories of their lives. The International Summer Institute in Sicily has given me an opportunity to study a culturally diverse and intellectually exciting – though neglected – region while offering my students a chance to engage in some of the most meaningful learning they have done in their lives. It has been a fascinating professional – as well as a personal – journey and one for which I am very grateful. 5 Dr. Dawn Marie Hayes is Associate Professor of European History at Montclair State University in New Jersey.