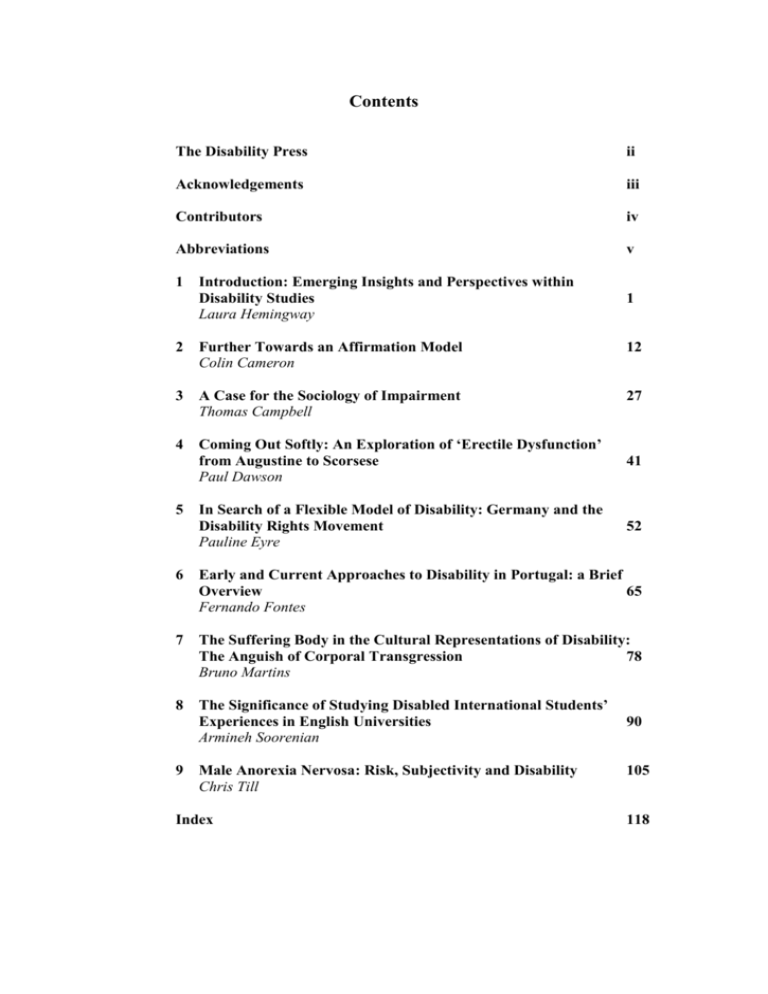

Contents - Centre for Disability Studies

advertisement