Easing the Pain: Biblical Criticism and Undergraduate Students

advertisement

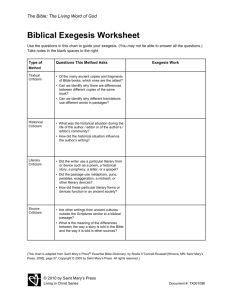

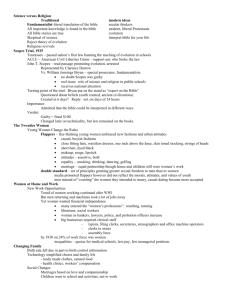

Easing the Pain: Biblical Criticism and Undergraduate Students CCCU New Faculty Workshop Terry Brensinger Throughout the centuries, the Bible has been approached in a great variety of ways. Even a casual reading of the history of biblical interpretation reveals the allegorical, typological, and dogmatic methods, among others. In recent years, however, the field of biblical studies has become increasingly dominated by the historical-critical method of interpretation. The name "historical -critical interpretation" is actually an overarching label that includes various descriptive methods, such as literary, form, and redaction criticism. Together, these specific techniques constitute a general approach to the Scriptures that is characterized by three major objectives: (1) to consider the historical dimensions of the biblical text, including the original setting and concerns of each book; (2) to critically analyze and evaluate the data; and (3) to arrive at a fresh interpretation of the text(s) in question rather than to corroborate necessarily any preexisting conceptions. As straightforward as this interpretive approach might appear, its rise to prominence has been met with varying and conflicting responses. Fundamentalists have and continue to reject it, claiming that the overly rationalistic and naturalistic tendencies associated with many of the method's practitioners are intrinsic to the method itself.1 At the same time, many of the method's traditional supporters have grown increasingly dissatisfied with the theological and spiritual vacuum that repeatedly results whenever historical criticism goes unchecked.2 As a result, one can sense an ever-enlarging camp, made up of both so-called evangelicals and liberals, who employ to varying degrees the historical-critical method while acknowledging divine activity and attending to the spiritual well-being of the community of faith. It is in this camp that I find myself, and I would second Boer's summation of the situation: From a purely formal point of view, therefore, biblical criticism stands on one line with music criticism, literary criticism, and artistic criticism. From a formal theological point of view it stands on one line with the disciplines known as doctrine, exegesis, church history, and homiletics. All of these can be well or poorly pursued, but no one in his right mind would say that any of them is inherently evil. 3 In other words, you do not judge the method on the basis of those who misuse it, anymore than you judge a wrench on the basis of the mechanic who uses one to beat his employer over the head. Rather, you evaluate the real and potential contributions of the method itself. In my estimation, historical-critical interpretation as a method has much to commend it. Furthermore, the problems that have resulted from its practice are due primarily to an obsession with objectivity that prevents any personal identification with the Bible itself, a failure to acknowledge the method's limitations, and a lack of accountability outside of scholarly circles. 4 Given this bit of background, the primary issue facing those teachers who wish to introduce critical questions to their undergraduate Bible students concerns the manner in which this ought to be done. While this issue could be addressed in a number of ways, I hope to explore in the remainder of this discussion some basic attitudes and ideas that are of value when incorporating historical-critical matters into the teaching process. A. Sensitivity The teacher must begin by approaching such situations with sensitivity toward the students. It is far too easy to simply conclude that the average undergraduate student is either uninformed, misinformed, or unwilling to consider alternate points of view. We of ten fail to realize, however, that such surface responses merely conceal emotional struggles. In Healing of Memories, David Seamands discusses the possible emotional underpinnings of seemingly theological differences.5 A young person arguing against the goodness of God, for example, may be subtly expressing anxieties about her own abusive father more so, than articulating biblically-derived conclusions. In the same way, the raising of critical issues and questions often arouses deep emotional responses. What might at first appear to be a stubborn narrowmindedness may actually be a fear of uncertainty-an uneasiness concerning the threat to one's foundational beliefs and the perceived alteration in one's identity. Along these same lines, Walter Wink has adapted one of Paul Ricoeur's paradigms in order to conceptualize the various stages through which people travel as far as their views of the Bible are concerned. The resulting paradigm looks like this: 1. 2. 3. FUSION DISTANCE COMMUNION (First Naivete) (Historical-Critical Process) (Second Naivete) The first stage, fusion or first naivete, is where the majority of us begin our journey with the Bible. In this stage, the Bible, figuratively speaking, can do no wrong. It would be a mistake, however, to automatically attribute such an understanding to a meaningful faith commitment. We have all witnessed ardent defenders of this point of view who fail in many regards to take the Bible seriously. Rather, it is frequently an unreflective and untested position in which the Bible is seen as perfectly unified in every respect and with no apparent limitations. L'Heureux likens this perception of the Bible to the young child identifying with her parents.6 "My mommy is the greatest cook in the world" or "My daddy can do anything" reflect such a perspective. Needless to say, various individuals, particularly from the most conservative constituencies, never leave this initial stage. Somewhere during the journey, however, many people encounter critical issues and unanswerable questions that force them to examine their stage-one convictions. In a sense, this experience is similar to the young child realizing that mommy and daddy do in fact have limitations. Such an awareness often has deep emotional implications as the blissful state passes into reality. With respect to the Bible, the simplicity of stage one is at times replaced by severe doubt and criticism in stage two. Like the liberated college freshman who, free from parental restraints, explores all avenues of this new-found freedom, so too does the student of Scripture choose to ignore, dominate, dissect, or control the Bible. Rather than being a profound and cherished source of spiritual transformation, the Bible becomes an impersonal object that stands in a barren desert somewhere outside of the self and beyond the realm of human experience. If various individuals have never left stage one, then it can also be said that others, including many of the practitioners of the historical -critical method, have taken up permanent residence here in stage two. But as most would agree that it is vitally important for children to gain a more realistic perception of their parents, so too do I think that it is crucial for students of the Bible to experience something of stage two. Stage two, however, must never be the end of the journey. Rather, teachers must sensitively seek for ways to lead students into stage three, the second naivete. Here, the unreflective simplicity of stage one is replaced with a profound appreciation for the complexity of the text, while at the same time the transforming power of Scripture is both affirmed and realized. Having been changed as a result of stage-two experiences, the student can now replace neatly defined theological boxes with an exploratory faith that affirms the authority of Scripture without reducing it to the narrowest of confines. In my estimation, stage three is clearly the goal of teaching and, indeed, discipleship. However, the journey is at times a painful and emotional one. For those who have already made the trip or are at least well on the way, it is far too easy to forget the pot-holes and sharp curves that were encountered during earlier travels. To teach effectively, great sensitivity is needed. Students may not simply be uninformed, misinformed, or unwilling to consider alternate points of view. They may be struggling with the pains of growing up. B. Humility In addition to sensitivity, teachers introducing critical issues should be characterized by humility. A great temptation facing teachers in such situations is to create an illusion of certainty. Certainty is frequently seen as a sign of strength, and people, whether students or citizens, like to see strength in their teachers or officials. Similarly, those in positions of authority enjoy being perceived as strong and confident. The problem, however, is that strength and confidence need to be expressed in areas where confidence rightly exists. To do otherwise is to mislead or delude. In teaching, strength and confidence are indeed important characteristics. but these must be tempered by humility and a continuing inquisitiveness, particularly when critical questions remain wide open. In my estimation, one of the greatest weaknesses of historical -critical interpretation has been the tendency, both on the printed page and in public presentation, to create a sense of certainty when such certainty does not exist. In so doing, the end of the quest is already defined and alternate points of view disregarded (the very same accusation typically made against fundamentalists!). Along these same lines, Ratzinger has called for a self- criticism of the historical-critical method. Interestingly enough, this is precisely Where he suggests that criticism should begin: The self-critique of historical method would have to begin, it seems, by reading its conclusions in a diachronic manner so that the appearance of a quasiclinical-scientific certainty is avoided. It has been this appearance of certainty which has caused its conclusions to be accepted so far and wide.7 Given the wide range of topics that historical-critical interpretation addresses, there are understandably varying degrees of certainty from subject to subject. Needless to say, some things are far more clear than others. The point, however, is that teachers introducing critical issues must resist the temptation to substitute dogmatism for honest conversation. After all, the critical method itself arose in part as a reaction against the Dogmatic Theology so prevalent prior to the Enlightenment! As in virtually every area of life, accountability is crucial if one hopes to experience both the encouragement and correction that others have to offer. The nature of such accountability, of course, depends to a great extent upon who is included and excluded from one's supporting community. In Biblical Studies, as is often and perhaps more justifiably the case in other disciplines, the supporting community has increasingly become the circle of scholars. More books are being written, but fewer are being read as the intended audience continues to be more narrowly defined. In a sense, scholars write articles and books for each other. As consequences, the community of faith in general often fails to benefit from the significant insights gained through historical-critical interpretation, and the questions asked by ordinary human beings often go unheard by those in scholarly circles. In contrast to this narrowing of the audience, I maintain that the community of accountability, while certainly including those in the scholarly world, must be expanded to include the church in a broader sense. As Sanders expresses the same conviction, "the believing community always was and always will be the proper Sitz im Leben of canon."8 Or in the words of Barr: The Bible takes its origin from within the life of believing communities; it is interpreted within the continuing life of these communities; the standard of its religious interpretation is the structure of faith which these communities maintain; and it has the task of providing a challenge, a force for innovation and a source of purification, to the life of these communities.9 If this is so, then teachers must explore ways of including others in their community of accountability. In order to take this seriously, I have attempted to expand my own community of accountability to include at least three groups. The first two, which go somewhat beyond the scope of this discussion, include teaching Bible classes in churches/camps as well as the more traditional conversing with colleagues at Messiah and elsewhere (conferences, professional meetings, and so on). The third, however, directly relates to my courses here at the college. When introducing students to new and potentially disquieting issues and ideas, I publically affirm the fact that I myself am on the journey with them and I invite them to hold me accountable for what I say. I initially tried this when I taught Pentateuch for the first time. In approaching the creation accounts, I asked the students to hold me accountable for everything I said, and I was amazed at how honest and nonthreatening the resulting discussion was. An open community of accountability, while seemingly risky for the teacher at first, is essential in conversing about critical issues of faith and the Bible. D. Malleability Given the importance of sensitivity, humility, and accountability, the teacher must finally be malleable. In this case, malleability refers not so much to class structures, techniques, and dynamics, concern for which is assumed in the previous categories, but moreso to the attitude and devotion which the teacher brings to the Bible in particular and the Christian life in general. For ultimately, the finest test of one's convictions lies in an unwavering willingness to live by them. Throughout the post-Enlightenment years, it has been common for practitioners of the historical-critical method to seek total objectivity when approaching the text. Included in this quest was a disregard for anything that defied historical verification.10 What typically resulted was either a denial of divine activity or an obsessive attempt to set the testimonies of such activity aside. In more recent years, however, it has become increasingly clear that to approach the Bible purely from this point of view is to do a gross injustice to the very nature of Scripture. While an awareness of one's own personal, religious, and national prejudices and biases is both desirable and instructive, the disregarding of foundational faith commitments and a sense of expectation leaves one holding a full but covered glass without a straw. In the words of Fretheim: ... given the fact that the original writers were not neutral and "objective," the more detached we seek to be when we read the text, the less likely we will be to hear it in the way that they intended."11 Or as Ratzinger expresses the same conviction: It [exegesis] must recognize that the faith of the Church is that form of "sympathia" without which the Bible remains a closed book. It must come to acknowledge this faith as a hermeneutic, the space for understanding, which does not do dogmatic violence to the Bible, but precisely allows the solitary possibility for the Bible to be itself.12 The teacher must, in short, come to the text ready to learn, not simply from the ordinary, but from the extraordinary as well. Committed to what Stuhlmacher refers to as "a hermeneutic of consent iinverstandnis, "13 he will engage in an approach that enables him to live in conformity to Scripture. Rather than simply expecting students to adjust their ideas and ways of living, the teacher will model a profound appreciation for Scripture and a desire to have his own life conform to its instruction, even when personal alteration is the price. In short, the teacher's eagerness to learn from the Bible and willingness to change in the light of that learning is absolutely crucial. So often, students shun critical ideas and difficult questions because they fear that a loss of faith inevitably lies somewhere around the corner. When they are invited to see first-hand that true faith and critical thinking can live nicely together, their defenses begin to fall. So much of introducing historical-critical issues, then, concerns the attitudes that the teacher brings along to the task. When sensitivity, humility, accountability, and malleability are integrated into the learning process, honest dialogue can take place and students and teacher alike are given a legitimate opportunity to grow. NOTES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. See, for example, Harold Lindsell, The Battle for the Bible (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1976). p. 82. According to Lindsell, "Orthodoxy and the historical-critical method are deadly enemies that are antithetical and cannot be reconciled without the destruction of one or the other." As examples, see Bernhard W. Anderson, "Tradition and Scripture in the Church," Journal of Biblical Literature 100 (Jan 1981): 5-21; Martin Hengel, Acts and the History of Earliest Christianity, trans. John Bowden (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), pp. 129-136; Gerhard Maier, The End of the HistoricalCritical Method, trans. Edwin W. Leverenz and Rudolph F. Norden (St. Louis: Concordia, 1977), pp. 11-47; and Walter Wink, The Bible in Human Transformation (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1973). Paul Ricoeur captures the sentiment rather descriptively when he writes, "Beyond the desert of criticism we wish to be called again." See Ricoeur, The Symbolism of Evil, trans. Emerson Buchanan (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), p. 349. Harry R. Boer, The Bible and Higher Criticism (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1981), p. 17. For a useful evaluation of both the strengths and weaknesses of historical-critical interpretation, see Edgar Krentz, The Historical-Critical Method (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1975), pp. 63-72; and Willard Swartley, "Beyond the Historical-Critical Method," in Essays on Biblical Interpretation: Anabaptist-Mennonite Perspectives, ed. Willard Swartley (Elkhart, IN: Institute of Mennonite Studies, 1984), pp. 237-264 (specifically 240-248). David Seamands, Healing of Memories (Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1985), pp. 113-117. Conrad E. L'Heureux, Life Journey and the Old Testament (New York: Paulist Press, 1986), p. 169. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, "Biblical Interpretation in Crisis: On the Question of the Foundations and Approaches of Exegesis Today," This World 22 (Summer 1989): 7. Reprinted in Richard John Neuhaus, gen. ed. Biblical Interpretation in Crisis: The Ratzinger Conference on Bible and Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), p. 6. James A. Sanders, "The Bible as Canon," The Christian Century (Dec. 2, 1981), p. 1252. James Barr, The Scope and Authority of the Bible (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1980), p. Ill. See, for example, Ernst Troeltsch's classic essay entitled "On the Historic and Dogmatic Methods in Theology," published in Gesammelte Schriften, vol. I (TUbingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1913), pp. 728-53. Terence E. Fretheim, Deuteronomic History (Nashville: Abingdon, 1983), p. 13. Ratzinger, p. 19. Peter Stuhlmacher, Vom Verstehen des Neuen Testament: Eine Hermeneutik (Gdttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1979), p. 206.