GENDER MARKER TIP SHEET

PROTECTION SECTOR

Gender Equality in the Project Sheet

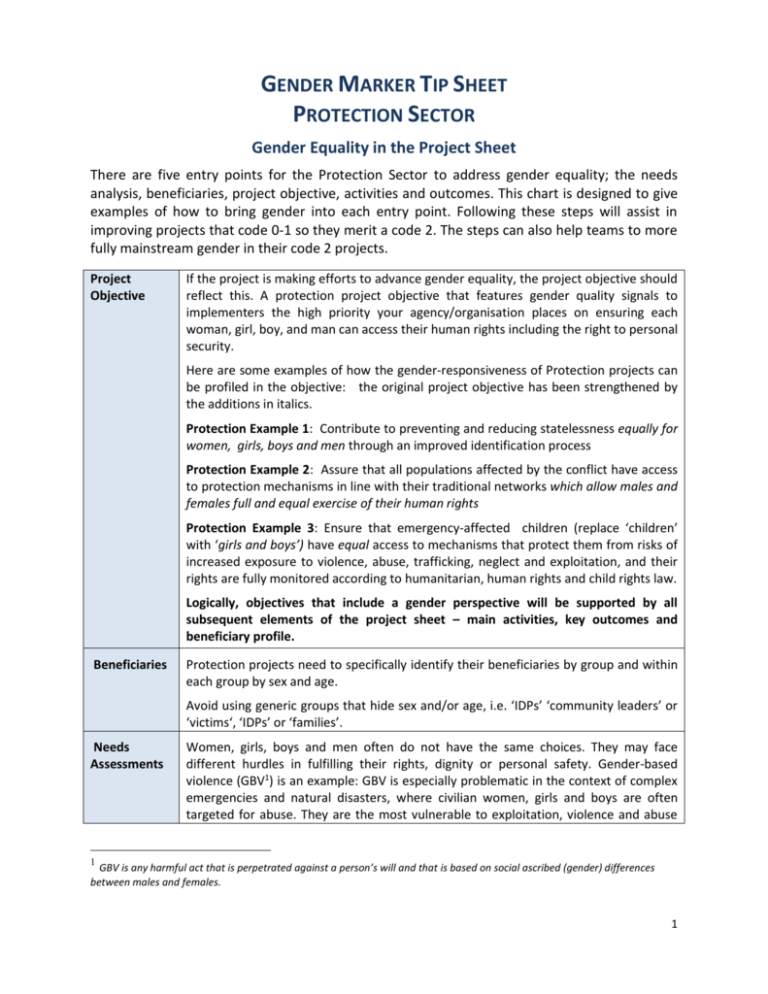

There are five entry points for the Protection Sector to address gender equality; the needs

analysis, beneficiaries, project objective, activities and outcomes. This chart is designed to give

examples of how to bring gender into each entry point. Following these steps will assist in

improving projects that code 0-1 so they merit a code 2. The steps can also help teams to more

fully mainstream gender in their code 2 projects.

Project

Objective

If the project is making efforts to advance gender equality, the project objective should

reflect this. A protection project objective that features gender quality signals to

implementers the high priority your agency/organisation places on ensuring each

woman, girl, boy, and man can access their human rights including the right to personal

security.

Here are some examples of how the gender-responsiveness of Protection projects can

be profiled in the objective: the original project objective has been strengthened by

the additions in italics.

Protection Example 1: Contribute to preventing and reducing statelessness equally for

women, girls, boys and men through an improved identification process

Protection Example 2: Assure that all populations affected by the conflict have access

to protection mechanisms in line with their traditional networks which allow males and

females full and equal exercise of their human rights

Protection Example 3: Ensure that emergency-affected children (replace ‘children’

with ‘girls and boys’) have equal access to mechanisms that protect them from risks of

increased exposure to violence, abuse, trafficking, neglect and exploitation, and their

rights are fully monitored according to humanitarian, human rights and child rights law.

Logically, objectives that include a gender perspective will be supported by all

subsequent elements of the project sheet – main activities, key outcomes and

beneficiary profile.

Beneficiaries

Protection projects need to specifically identify their beneficiaries by group and within

each group by sex and age.

Avoid using generic groups that hide sex and/or age, i.e. ‘IDPs’ ‘community leaders’ or

‘victims‘, ‘IDPs’ or ‘families’.

Needs

Assessments

Women, girls, boys and men often do not have the same choices. They may face

different hurdles in fulfilling their rights, dignity or personal safety. Gender-based

violence (GBV1) is an example: GBV is especially problematic in the context of complex

emergencies and natural disasters, where civilian women, girls and boys are often

targeted for abuse. They are the most vulnerable to exploitation, violence and abuse

1

GBV is any harmful act that is perpetrated against a person’s will and that is based on social ascribed (gender) differences

between males and females.

1

simply because of their sex, age and status in society.

In addition to GBV, women, girls, boys and men face struggles in the other pillars of

protection: housing, land and property rights; child protection; mine action and the

Rule of Law/Access to Justice. Therefore, a gender analysis is vital in the needs

assessment that informs any protection project.

Here are examples of questions that can enrich the design of protection projects:

What are the demographics of our target group? (# of households and family

members disaggregated by sex and age; # of single heads of household who are

women, girls, boys and men; # of unaccompanied children, elderly persons,

persons with disabilities, the chronically ill, pregnant and lactating women)

What personal security risks did women, girls, boys and men face before the

emergency (including in accessing food, water and fuel; in access to land and

markets; access to and participation in school; participation in paid work; access to

health services and facilities; and, access and participation in cultural,

community and social networks?

What has changed: what concerns do women, girls, boys and men now have about

their personal safety?

What actions do women, girls, boys and men want to be taken to increase their

personal security?

Do cultural norms enable women and men to participate equally in decisionmaking in their homes and communities? If not, what affirmative action is needed

so both can participate in a meaningful way in IDP/refugee/returnee communities?

Access to personal security and other rights is often blocked if a woman, girl, boy or

man either cannot speak up or no-one listens.

Are there discriminatory practices (or laws) that disadvantage either men/boys or

women/girls, or vulnerable subgroups of either sex, and prevent them from

exercising their rights to: food, water and NFIs; information; justice and legal

rights; health and education services; land?

What knowledge do women, girls, boys and men have about their legal rights,

sexual and gender-based violence, STIs, recruitment, mine action, etc.?

Who are the most effective messengers and what are the most effective methods

to bring rights education to women, girls, boys and men?

Are gender and protection issues being systematically addressed/monitored in:

Governance: An active multi-sectoral mechanism to prevent and respond to

gender-based violence within the disaster-affected population and a pro-active

mechanism to prevent humanitarian actors from committing sexual exploitation

and abuse (PSEA)2.

Facility design: Privacy in shelters; separate, lit, well-located toilets/

showers/water-points for males and females; safe and accessible common-use

areas for females and males; safe spaces for breastfeeding, peer discussions and

psycho-social counselling for M/F children, adolescents and adults.

NFIs. Appropriate locally-preferred sanitary supplies and contraceptives; culturally

appropriate clothing for males and females of different ages.

See the IASC Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings.

2

UN policy stipulates ‘zero tolerance’ for sexual exploitation and abuse. Sexual violence in armed conflict is a crime against

humanity.

2

Activities

The gender analysis in your needs assessment will identify gender gaps that need to be

addressed. These should be integrated into activities. Examples:

Gap: During the needs assessment women reported two young girls had been left

pregnant by the de-mining teams who set up camp near the returnee village during

their 12 weeks of demining.

Responsive activity: Orient all private contractors, including de-miners, in the

standards the UN requires of contractors. These include compliance with the SG’s

Bulletin on Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual

Abuse. All contractors and sub-contractors should be required in their contracts to

comply with the SG’s Bulletin. Rigorous monitoring should ensure violations result

in immediately cancelled contracts and trigger responsive services for the victims.

Gap: To get valid data on the affected population, humanitarian actors were doing

regular sunrise counts of the ‘night dwellers’- people, largely women, girls and

boys- who walk to the town each night for protection from rebel abduction. They

sleep in any secure area, whether in public works yards or school grounds, that is

not on the town fringe and where there is fencing, water and light. Most men stay

on their subsistence farms protecting their remaining possessions. It soon became

apparent that counting ‘children’ night dwellers and ‘children’ attending school

was hiding how many girls compared to how many boys were being abducted or

pulled out of school for other reasons.

Responsive activity: Ensure the project collects data on the affected population by

sex and age routinely. In conflict and disaster-affected areas, the protection issues

for women, girls, boys and men can not only be different at the onset of the

emergency but change with emerging circumstances. In the situation above,

identifying that the ratio of girls to boys is changing prompts project teams to

explore why and what can be done.

Gap: As government officials advised that it would be difficult to get female data

collectors for the host community assessment, an all-male team was recruited. This

team interviewed primarily male leaders. They raised no personal protection issues

but did raise property protection issues.

Responsive activities: Pro-actively seek equal numbers of men and women as data

collectors and information sources – there are always ways of supporting women to

participate; provide gender orientation to all data collectors to ensure they

understand why it is important to explore the differences between the realities of

women/girls and men/boys and know how to listen and record this information

accurately; ensure analysis explores the ‘root causes’ of fears and threats. These

can be an early warning of violence to come. In many environments sexual and

gender-based violence, in its many paid and unpaid forms, is seldom discussed:

signals like those in this case warrant investigation, then action, facilitated by

people with GBV expertise. Projects for these target IDP-host populations would

benefit from a conflict resolution mechanism that involves equal numbers of

respected males and females, including adolescent girls and boys.

Outcomes

Outcomes should capture gender change: the change experienced by the males and

females who are the identified beneficiaries. Outcome statements should, wherever

possible, be worded so that any difference in outcome for males and females or in

3

male-female relations is visible. Avoid outcome statements that focus on ‘IDPs’ ‘police

officers’ ‘survivors’ that hide whether, or not, males and females equally benefit.

Examples of gender outcomes in protection projects: the importance of the words in

italics is explained.

Child-friendly learning spaces established in order to secure the return to school of

5,000 displaced school-aged children, including near equal numbers of girls and

boys, in Area ABC

Signals that boys and girls have an equal right to education. If near-equal numbers

are not being achieved, the reasons need to be explored and inform follow-up

projects. Protection issues that are distinct for girls and boys may explain the gap

Improved and continued GBV coordination

Reflects that creating a culture of protection for women, girls, boys and men

involves many disciplines, all sectors, government and non-government actors.

Relevant sex and age disaggregated data on extremely vulnerable individuals is

gathered, reported and integrated into a referral system.

Recognises that the sex and age of a person can affect personal security and access

to rights

All local partners now have near-equal numbers of male and female trainers with

capacity to train others in protection, human rights and other relevant issues

Acknowledges that training roles are leadership roles and should be shared equally

by women and men. Also, male-to-male and female-to-female discussion and

facilitation may be required in some situations or, if not required, adds another

valuable dimension to male-female learning environments.

X% increase in the number of property titles in the joint name of husband and wife

or the name of a female head of household.

Advances equality before the law in land ownership and recognises that without

equal land ownership a woman’s choices may be severely restricted: without land

as collateral, there is often little access to credit.

4

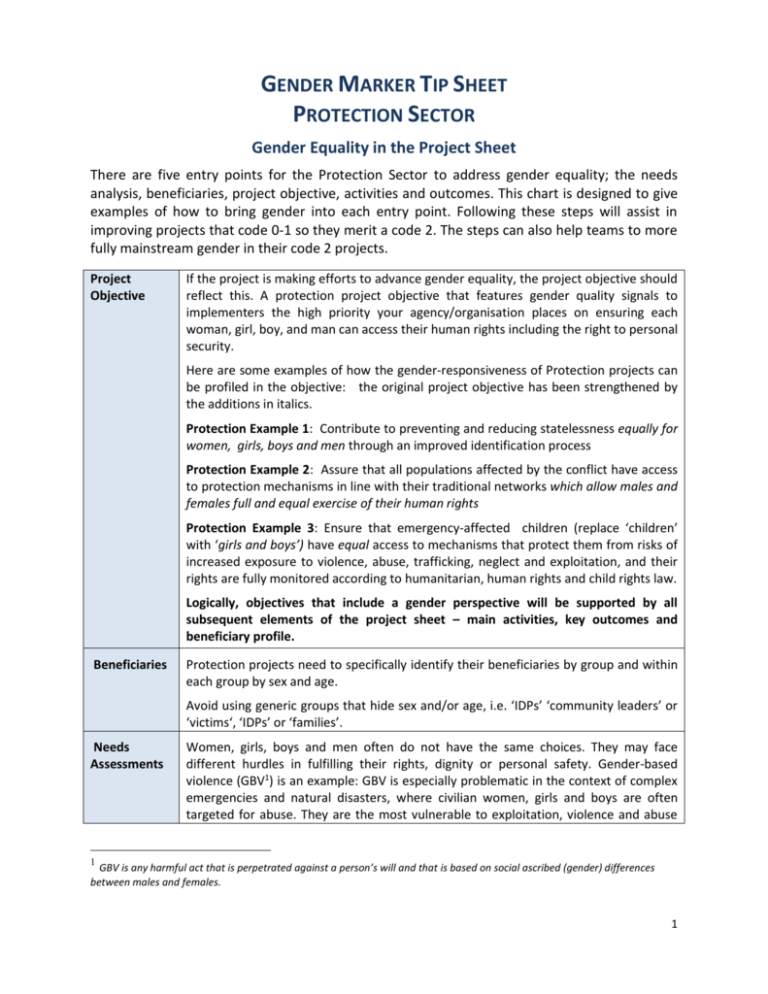

Gender Code*

Description

Note: The essential starting point for any humanitarian project is to identify the number of women, girls, boys and men who are the

target beneficiaries. This information is required in all project sheets.

Gender Code 3

Targeted Actions

Contributes

significantly to

gender equality

The project’s principal purpose is to advance gender equality

The gender analysis in the needs assessment justifies this project in which all activities and all

outcomes advance gender equality.

All targeted actions are based on gender analysis. In humanitarian settings, targeted actions are

usually of these two types:

1. The project assists women, girls, boys or men who suffer discrimination.

The project needs analysis identifies the women, girls, boys and men who are acutely

disadvantaged, discriminated against or lacking power and voice to make the most of their lives.

Targeted actions aim to reduce the barriers so all women, girls, boys and men are able to exercise

and access their rights, responsibilities and opportunities. Because the primary purpose of this

targeted action is to advance gender equality, the code is 3.

2.

The project focuses all activities on building gender-specific services or more equal relations

between women and men.

The analysis identifies rifts or imbalances in male-female relations that generate violence;

undermine harmony or wellbeing within affected populations, or between them and others; or

prevent humanitarian aid from reaching everyone in need. As the primary purpose of this type of

targeted action is to address these rifts or imbalances in order to advance gender equality, the

code is 3.

Targeted actions are often designed as interim measures: they address gender gaps and create a

level playing field. Code 3 projects use targeted actions solely to address gender gaps & create

greater equality between women and men.

Gender Code 2

Gender

Mainstreaming

Contributes

significantly to

gender equality

A gender analysis is included in the project’s needs assessment and is reflected in a number of

the project’s activities and project outcomes.

Gender mainstreaming in project design is about making the concerns and experiences of

women, girls, boys and men an integral dimension of the core elements of the project: gender

analysis in the needs assessment leads to gender-responsive activities and related gender

outcomes. This careful gender mainstreaming in project design facilitates gender equality then

flowing into implementation, monitoring and evaluation. This intention, and a design that plans

for measurement of gendered outcomes, is clearly articulated throughout the project sheet

Most humanitarian projects should aim for code 2. In a perfect world, targeted actions would not

be needed and the highest quality project, from a gender perspective, would be a project that

fully mainstreams gender. Today, both gender targeted and mainstreamed projects are needed.

Gender Code 1

Contributes in

some limited way

to gender

equality

Gender Code 0

May not

contribute to

gender equality

The project includes gender equality in the needs assessment, in an activity or in an outcome.

However, there is no clear indication that gender analysis flows from the needs assessment into

activities or their related outcomes. These projects have pieces, like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle,

but not enough pieces to fit together ensuring male and female beneficiaries’ needs are both

addressed. The project design does not guarantee that the project will have a positive impact on

gender inequality.

Gender is not reflected anywhere in the project sheet. There is risk that the project will

unintentionally nurture existing gender inequalities or deepen them.

5