Manet Picasso reading

advertisement

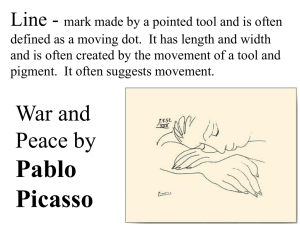

These are roughly the questions you’ll be answering in an in-class writing assessment. Articles follow to help you with your explanations and analysis. Study Manet's Le Dejeuner Sur L'Herbe and Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Knowing that America is steeped in Puritanical history and France is still a largely Catholic country, explain the reaction of the academics and the populace to both of these paintings. Address the social expectations of the Puritans and the Catholics and how these pieces of art may have defied (gone against) their principles. Knowing the social and religious context, was the reaction justified? Knowing the future we live in, was it an overreaction, or was it the gateway to the future we live in? Explain. PBS : Pablo Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon With Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, the Spanish painter Pablo Picasso offends the Paris art scene in 1907. Showing his eight-foot-square canvas to a group of painters, patrons, and art critics at his studio, Picasso meets with almost unanimous shock, distaste, and outrage. The painter Matisse is angered by the work, which he considers a hoax, an attempt to paint the fourth dimension. "It was the ugliness of the faces that froze with horror the half-converted," the critic Salmon writes later. The painter Derain comments wryly, "One day we shall find Pablo has hanged himself behind his great canvas." Keep in mind, this is coming from the two most noted Fauves who had been named the wild beasts for their outlandish use of color and throwing off of convention. In the months leading up to the painting's creation, Picasso struggles with the subject -five women in a brothel. He creates more than 100 sketches and preliminary paintings, wrestling with the problem of depicting threedimensional space in a two-dimensional picture plane. The original composition includes two men -- a patron surrounded by the women, and a medical student holding a skull, perhaps symbolizing that "the wages of sin are death." In the final composition, the patron is gone and the medical student -- who has been called a stand-in for the painter himself -- has become a fifth woman with a primitive mask, holding back the crimson curtain to reveal her "sisters." The painting is described as a battleground, with the remains of the battle left on the canvas. The Iberian women in the center of the canvas clash with the hideously masked creatures standing and squatting on the right. In creating Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Picasso turns his back on middle-class society and the traditional values of the time, opting for the sexual freedom depicted in a brothel. He also rejects popular current movements in painting by choosing line drawing rather than the color- and lightdefined forms of Impressionism and the Fauves. The painter's private demons take shape in the figures on the canvas. Picasso later calls Les Demoiselles d'Avignon "my first exorcism painting." He likens the act of painting to that of creating fetishes, or weapons: "If we give spirits a form, we become independent." The originality of Picasso's vision and execution in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon help plant the seeds for cubism, the widely acclaimed and revolutionary art movement that he and painter Georges Braque develop in years to come. After its initial showing, the painting remains largely unseen for 39 years. It is shown at the Galerie d'Antin in Paris in 1916, then lies rolled up in Picasso's studio until it is bought in the early 1920s by Jacques Doucet, sight unseen. It is reproduced in the publication La Revolution Surrealiste in 1925, but remains relatively unknown until 1937, when it is shown at the Petit Palais in Paris. The Museum of Modern Art in New York buys it soon afterwards, and in later years it becomes a prized part of the collection. From The Success and Failure of Picasso by John Burger, 1965: Blunted by the insolence of so much recent art, we probably tend to underestimate the brutality of the Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. All his friends who saw it in his studio were at first shocked by it. And it was meant to shock… A brothel may not in itself be shocking. But women painted without charm or sadness, without irony or social comment, women painted like the palings of a stockade through eyes that look out as it at death – that is shocking. And equally the method of painting. Picasso himself has said that he was influenced at the time by archaic Spanish (Iberian) sculpture. He was also influenced – particularly in the two heads at the right – by African masks…here it seems that Picasso’s quotations are simple, direct, and emotional. He is not in the least concerned with formal problems. The dislocations in this picture are the result of aggression, not aesthetics; it is the near you can get in a painting to an outrage… I emphasize the violent and iconoclastic aspect of this painting because it is usually enshrined as the great formal exercise which was the starting point of Cubism. It was the starting point of Cubism, in so far as it prompted Braque to begin painting at the end of the year his own far more formal answer to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon…yet if he had been left to himself, this picture would never have led Picasso to Cubism or to any way of painting remotely resembling it…It has nothing to with that twentieth-century vision of the future which was the essence of Cubism. Yet it did provoke the beginning of the great period of exception in Picasso’s life. Nobody can know exactly how the change began inside Picasso. We can only note the results. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, unlike any previous painting by Picasso, offers no evidence of skill. On the contrary, it is clumsy, overworked, unfinished. It is as though his fury in painting it was so great that is destroyed his gifts… In 1863, Manet shocked the French public by exhibiting his Déjeuner sur l'herbe ("Luncheon on the Grass"). It is not a realist painting in the social or political sense of Daumier, but it is a statement in favor of the artist's individual freedom. The shock value of a nude woman casually lunching with two fully dressed men, which was an affront to the propriety of the time, was accentuated by the familiarity of the figures. Manet's wife, Suzanne Leenhoff, and his favorite model, Victorine Meurent, both posed for the nude woman, which has Meurent's face, but Leenhoff's plumper body.[citation needed] Her body is starkly lit and she stares directly at the viewer. The two men are Manet's brother Gustave Manet and his future brother-in-law, Ferdinand Leenhoff. They are dressed like young dandies. The men seem to be engaged in conversation, ignoring the woman. In front of them, the woman's clothes, a basket of fruit, and a round loaf of bread are displayed, as in a still life. In the background a lightly clad woman bathes in a stream. Too large in comparison with the figures in the foreground, she seems to float above them. The roughly painted background lacks depth – giving the viewer the impression that the scene is not taking place outdoors, but in a studio. This impression is reinforced by the use of broad "photographic" light, which casts almost no shadows: in fact, the lighting of the scene is inconsistent and unnatural. The man on the right wears a flat hat with a tassel, of a kind normally worn indoors. Despite the mundane subject, Manet deliberately chose a large canvas size, normally reserved for historical subjects. The style of the painting breaks with the academic traditions of the time. He did not try to hide the brush strokes: indeed, the painting looks unfinished in some parts of the scene. The nude is a far cry from the smooth, flawless figures of Cabanel or Ingres. Commentary of Émile Zola The Luncheon on the Grass is the greatest work of Édouard Manet, one in which he realizes the dream of all painters: to place figures of natural grandeur in a landscape. We know the power with which he vanquished this difficulty. There are some leaves, some tree trunks, and, in the background, a river in which a chemisewearing woman bathes; in the foreground, two young men are seated across from a second woman who has just exited the water and who dries her naked skin in the open air. This nude woman has scandalized the public, who see only her in the canvas. My God! What indecency: a woman without the slightest covering between two clothed men! That has never been seen. And this belief is a gross error, for in the Louvre there are more than fifty paintings in which are found mixes of persons clothed and nude. But no one goes to the Louvre to be scandalized. The crowd has kept itself moreover from judging The Luncheon on the Grass like a veritable work of art should be judged; they see in it only some people who are having a picnic, finishing bathing, and they believed that the artist had placed an obscene intent in the disposition of the subject, while the artist had simply sought to obtain vibrant oppositions and a straightforward audience. Painters, especially Édouard Manet, who is an analytic painter, do not have this preoccupation with the subject which torments the crowd above all; the subject, for them, is merely a pretext to paint, while for the crowd, the subject alone exists. Thus, assuredly, the nude woman of The Luncheon on the Grass is only there to furnish the artist the occasion to paint a bit of flesh. That which must be seen in the painting is not a luncheon on the grass; it is the entire landscape, with its vigors and its finesses, with its foregrounds so large, so solid, and its backgrounds of a light delicateness; it is this firm modeled flesh under great spots of light, these tissues supple and strong, and particularly this delicious silhouette of a woman wearing a chemise who makes, in the background, an adorable dapple of white in the milieu of green leaves. It is, in short, this vast ensemble, full of atmosphere, this corner of nature rendered with a simplicity so just, all of this admirable page in which an artist has placed all the particular and rare elements which are in him.[4] This famous painting has remained controversial, even to this day. Odilon Redon, for example, did not like it. There is a discussion of it, from this point of view, in Proust's Remembrance of Things Past. One interpretation of the work is that it depicts the rampant prostitution that occurred in the Bois de Boulogne, a large park at the western outskirts of Paris, at the time. This prostitution was common knowledge in Paris, but was considered a taboo subject unsuitable for a painting. Indeed, the Bois de Boulogne is to this day known as a pick-up place for prostitutes and illicit sexual activity after dark, just as it had been in the 19th century. Useful terms and background information… Bourgeois: a word often used by modern artists and writers when speaking of the common masses who are most concerned with their daily lives and not so much with making statements or fostering political change. noun 1. a member of the middle class. 2. a person whose political, economic, and social opinions are believed to be determined mainly by concern for property values and conventional respectability. 3. a shopkeeper or merchant. adjective 4. belonging to, characteristic of, or consisting of the middle class. 5. conventional; middle-class. 6. dominated or characterized by materialistic pursuits or concerns. Catholic teachings on sexual morality draw from natural law, Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition. Sexual morality evaluates the goodness of sexual behavior, and often provides general principles by which Catholics are able to evaluate the morality of specific actions. The Catholic Church teaches that human life and human sexuality are both inseparable and sacred. Because Catholics believe God created human beings in his own image and likeness and that he found everything he created to be "very good”, the Catholic Church teaches that human body and sex must likewise be good. The Catechism teaches that "the flesh is the hinge of salvation." The Church considers the expression of love between husband and wife to be an elevated form of human activity, joining as it does, husband and wife in complete mutual self-giving, and opening their relationship to new life. “The sexual activity, in which husband and wife are intimately and chastely united with one another, through which human life is transmitted, is, as the recent Council recalled, ‘noble and worthy.’” It is in cases in which sexual expression is sought outside sacramental marriage, or in which the procreative function of sexual expression within marriage is deliberately frustrated, that the Catholic Church expresses grave moral concern. However the Church does teach that sexual intercourse outside of marriage is contrary to its purpose. The "conjugal act" aims at a deeply personal unity, a unity that, beyond union in one flesh, leads to forming one heart and soul" since the marriage bond is to be a sign of the love between God and humanity. Among the sins gravely contrary to chastity are masturbation, fornication, pornography, homosexual practices and artificial contraception. What is a Puritan? Most students are taught that the first people that sailed the Atlantic for America, did so for religious freedom. As true as that may be, it does not mean that they wanted to “be free” in the hippy sense. They were intensely strict. Puritan culture emphasized the need for self-examination and the strict accounting for one’s feelings as well as one’s deeds. This was the centre of evangelical experience, which women in turn placed at the heart of their work to sustain family life. The words of the Bible, as they interpreted them, were the origin of many Puritan cultural ideals, especially regarding the roles of men and women in the community. While both sexes carried the stain of original sin, for a girl, original sin suggested more than the roster of Puritan character flaws. Eve’s corruption, in Puritan eyes, extended to all women, and justified marginalizing them within churches' hierarchical structures Authority and obedience characterized the relationship between Puritan parents and their children. Proper love meant proper discipline; the family was the basic unit of supervision. A breakdown in family rule indicated a disregard of God’s order. “Fathers and mothers have ‘disordered and disobedient children,’” said the Puritan Richard Greenham, “because they have been disobedient children to the Lord and disordered to their parents when they were young.” Because the duty of early childcare fell almost exclusively on women, a woman's salvation necessarily depended upon the observable goodness of her child. Puritans further connected the discipline of a child to later readiness for conversion. Accordingly, parents attempted to check their affectionate feelings toward a disobedient child, at least after the child was about two years old, in order to break his or her will. This suspicious regard of “fondness” and heavy emphasis on obedience placed pressures on the Puritan mother. While Puritans expected mothers to care for their young children tenderly, a mother who doted could be accused of failing to keep God present. A father’s more distant governance should check the mother’s tenderness once a male child reached the age of 6 or 7 so that he could bring the child to God’s authority In modern usage, the word puritan is often used to describe someone who is strict in matters of sexual morality, disapproves of recreation, and wishes to impose these beliefs on others. This popular image is more accurate as a description of Puritans in colonial America, who were among the most radical Puritans and whose social experiment took the form of a theocracy. The first Puritans of New England certainly disapproved of Christmas celebrations, as did some other Protestant churches of the time. Celebration was outlawed in Boston from 1659. The ban was revoked in 1681 by the English-appointed governor Sir Edmund Andros, who also revoked a Puritan ban on festivities on Saturday nights. Nevertheless, it was not until the mid-19th century that celebrating Christmas became fashionable in the Boston region. Likewise the colonies banned many secular entertainments, such as games of chance, maypoles, and drama, on moral grounds. They were not, however, opposed to drinking alcohol in moderation. Early New England laws banning the sale of alcohol to Native Americans were criticized because it was “not fit to deprive Indians of any lawfull comfort aloweth to all men by the use of wine.” Laws banned the practice of individuals toasting each other, with the explanation that it led to wasting God's gift of beer and wine, as well as being carnal. Bounds were not set on enjoying sexuality within the bounds of marriage, as a gift from God. In fact, spouses (albeit, in practice, mainly females) were disciplined if they did not perform their sexual marital duties, in accordance with 1 Corinthians 7 and other biblical passages. Puritans publicly punished drunkenness and sexual relations outside marriage.