Current Event I

advertisement

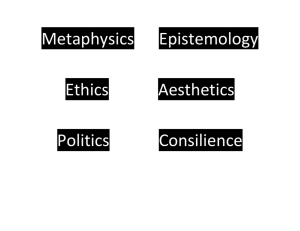

Kevin D. McMahon Student ID#: 78513 SED 625SC 9/17/06 Current Event I A Summary, Analysis & Reflection of: Scientifically Based Research in Education: Epistemology and Ethics By: Elizabeth Adams St. Pierre University of Georgia Adult Education Quarterly Volume 56 No. 4 239-266 August 2006 In this article the author, Elizabeth Adams St.Pierre, argues that the Department of Education under the direction of the current administration is attempting to impose a form of scientific positivism (scienticism) onto the field of education research and education in general. The author makes the following contentions in the article: (1) that the presumption of the Department of Education is that the field of education research is “broken,” (2) that the “…fix is to make it ‘scientific,’ and the federal government has taken the lead in this project by mandating scientific method in law,” (3) that No Child Left Behind (NCLB) has empowered federal agencies to establish a “culture of surveillance” through standardized testing whereby, (4) the scientific/positivistic paradigm can be efficiently imposed upon schools and, (5) by directing the flow of grant money towards education research that is conducted using prescribed scientific methodology the Department of Education will extend their “fix” to the Colleges of Education. It is this final contention, that Scientifically Based Research (SBR) or Evidence Based Research (EBR), is epistemological reductionism and scientific imperialism, where Ms. St.Pierre focuses most of her animus against the current regime. Ms. St.Pierre contends that science, as a means of knowing, is not often understood by those who practice it and even less by current policy makers who are attempting to impose it on the field of education research. If they did work their epistemology “for all it’s worth” they would “inevitably come up against…the limits of intelligibility…the boundary where thought stops what it cannot bear to know, what it must shut out to think as it does.” It is this inability or unwillingness to acknowledge the limits of scientific epistemology that has caused the current crisis in education research whereby a methodological approach is being mandated by the federal government. She expresses her concern by quoting Stephen Ball’s Orwellian warning that SBR, with its concomitant quantification of knowledge and knowing subjects, serves “the attempt to monitor, control and instrumentalize all and every facet of educational experience. To make us all to think about ourselves as individuals who calculate about ourselves, ‘add value’ to ourselves, improve our productivity, live an existence of calculation, make ourselves relevant.” The author proposes that the Department of Education, adopt a more pluralistic approach whereby a variety of epistemologies are acceptable with the domains of education research. Furthermore, she insists, that ethics demands inclusiveness because when we reject another “epistemology to shut out critique and keep our own intact, we are also rejecting the people who live that epistemology.” Finally, she defends those epistemologies that are inherently qualitative and subjective in their approach to knowledge as opposed to quantitative and objective which are the hallmarks of “scientism” or “positivism.” We must resist the tendency that those in power define what is knowledge, what knowledge is valuable, and how to acquire this knowledge. To reduce epistemology to science is to emphasize just one side of the fact/value and object/subject binaries impoverishing both the knowledge and the knower. We must, she concludes paraphrasing the deconstructionist Derrida, “allow oppositions to exits.” I believe that Ms. St.Pierre offers an important critique of the current emphasis on SBR. I am sure that as a Professor in the Department of Education you are acutely aware of this emphasis. I too have noted an increase in SBR vernacular at school site professional developments. I have had my qualms about this and the corollary tendency to reduce that which I do with my students to quantifiable data. In the past ten years my personal interests have tended to shift from “science” to philosophy. I have taught philosophy at my school site and one of the topics we focused on was the development of scientific epistemology. I may not be a great scientist or philosopher for that matter, but I have tried to push the “limits of intelligibility” of the epistemology that I teach. I am therefore sympathetic with Ms. St.Pierre’s concern about scientific chauvinism and although I may not agree with some of her deconstructionist approaches and conclusions I would certainly not want to limit her freedom to pursue such research. Now having exposed my sympathies, I must point out that she makes a comment that I believe requires some clarification (actually there are more than one but there is a limit to what can be discussed in this essay). She makes the comment that “science…ignored the voices of the disenfranchised.” Ms. St.Pierre takes great pains at objectifying science as a methodology for which I would agree. It is difficult to see how a methodology can “ignore the voices” of anyone albeit I am sure that there are plenty of scientists that have and continue to do so. But this is a function of human nature to which even deconstructionists like Ms. Pierre are subject, and not just scientists. An area that I believe needs clarification is whether she is seeking a broader definition of “science” whereby it incorporates within itself other epistemologies or rather that we acknowledge the limits of science as an epistemological endeavor and therefore make room for other epistemologies thereby filling in the gaps of knowing that are “unthought” by science. So in such references as: “So what are scientists to do when their science is, at best, proclaimed by the powerful to be prescientific and, at worst, rejecte,” she is suggesting that what she does employing deconstruction epistemology is science. On the other hand, she complains that “…the growth of scientific knowledge is the key accomplishment of the past three centuries in the West, it has been accompanied by an elaborate philosophical defense of a variety of exclusionary practices by which those deemed to be untrained in or unreceptive to such science are shunted aside or even denied opportunities to speak.” Perhaps she should have focused her article more along the lines that a particular narrow view of science has become dominant to the exclusion of other views. To this end, a brief history of the development of science may have been helpful for she seems to be arguing almost for a Baconian (Roger not Francis) definition of science as scientia which he developed as a more holistic epistemology in his Opus Majus. In her concluding paragraphs Ms. Pierre makes a bold and intellectually humble statement (one that I hope she and her deconstructionists colleagues abide should they someday take hold of the levers of power at the Department of Education): “…what I cannot imagine stands guard over everything that I must/can do, think, live [and] insists that I engage, rather than exclude, other epistemologies and the other who claims them in order to move towards the unthought…. this the breakdown of certainty, a willingness to be unsure and to learn to thrive in the restless, rigorous confusion that is learning— inquiry.”