APPENDIX A – Sample Forms & Guidance Documents

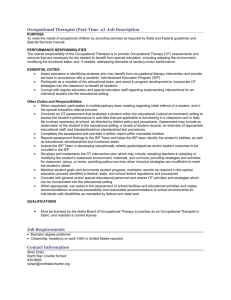

advertisement