vandana mishra - Clinical Trials Registry

advertisement

EVALUATION OF LABETALOL AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO

MAGNESIUM SULFATE IN THE PREVENTION OF

ECLAMPSIA

Protocol of Thesis to be submitted to the University of Delhi towards

Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of

Doctor of Medicine (Obstetrics & Gynaecology)

(Batch : 2009-2012)

by

VANDANA MISHRA

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology,

University College of Medical Sciences &

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital,

Delhi-110095

1

EVALUATION OF LABETALOL AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO

MAGNESIUM SULFATE IN THE PREVENTION OF

ECLAMPSIA

Protocol of Thesis to be submitted to the University of Delhi towards Partial

Fulfilment of the Requirement for the Degree of

Doctor of Medicine (Obstetrics & Gynaecology)

(Batch : 2009-2012)

…………………………………..

(Signature)

Student:

Dr. Vandana Mishra

Supervisor:

Dr. Gita Radhakrishnan

…………………………………..

Professor

(Signature)

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

UCMS & GTB Hospital

Co-Supervisor: Dr. Suchi Bhatt

Senior Consultant

Department of Radiology

UCMS & GTB Hospital

…………………………………..

(Signature)

Place of Work:

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology

University College of Medical Sciences &

Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, Delhi-110095

2

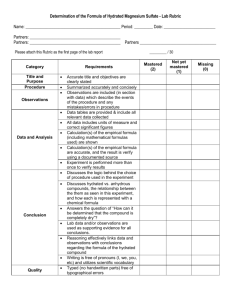

ABSTRACT

Background: Magnesium sulfate is use extensively for prevention of eclamptic

seizures. Empirical and clinical evidence supports the effectiveness of

magnesium sulfate, however, questions remain as to its mechanism of action

and safety profile. Labetalol, a known antihypertensive has been used safely for

many years to treat hypertension in preeclamptic women. Studies have shown

the role of labetalol in prevention of eclampsia in women with preeclampsia.

Study Design: Prospective randomized comparative active controlled clinical

trial.

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of labetalol in prevention of eclampsia in

women with severe pre-eclampsia.

Subjects: 60 patients with severe preeclampsia either in labour or requiring

termination of pregnancy will be included in the study.

Intervention: Patients will be divided in two groups to receive either labetalol

(oral or parenteral) or magnesium sulfate as per the standard protocol. Nifedipine

will be the additional anti hypertensive agent added in both the groups to attain

the target blood pressure.

Outcome measure: Primary outcome measure will include the occurrence of

eclamptic seizure(s) after enrolment in the study. Need for additional

antihypertensive agent, delivery parameters and complications or adverse drugs

effects in mother and intrapartum fetal distress and need and duration of NICU

admission in babies will be included in the secondary outcome measures.

Statistical analysis: Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test will be used for

categoric variables and Student’s t-test for continuous variables. p<0.05 will be

considered significant.

3

INTRODUCTION

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy constitute the commonest medical disorder

occurring in 6-8%of all pregnancies1. According to National High Blood Pressure

Education Programme (NHBPEP) Working Group and American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) hypertension in pregnancy is defined

as diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg or systolic blood pressure (SBP)

≥140 mmHg after 20 weeks of gestation in women with previously normal blood

pressure2,3. Pre-eclampsia is a multisystemic disorder of pregnancy usually

associated with raised blood pressure and proteinuria. Although the outcome in

mild cases is often good, in one-third cases the disease is severe and is a major

cause of maternal morbidity and mortality4,5 accounting for nearly 50,000 of direct

maternal deaths in a year worldwide6. Eclampsia, one of the most dreaded

complications of pre-eclampsia is defined as the occurrence in a woman with

pre-eclampia, of seizures that cannot be attributed to other causes. In developing

countries the estimates vary from 1 in 100 to 1 in 17007.

The pathophysiology of eclampsia is not clear but MRI and Doppler data suggest

that overperfusion of cerebral tissues is a major etiologic factor1,8. Doppler data

have shown that cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) is abnormally increased in

severe preeclampsia and the autoregulation of middle cerebral artery is affected

by this condition leading to increased CPP9,10. The level of CPP required to

cause barotrauma and seizures varies between individuals. However, it has been

seen that seizures also occur in women who have mild to no hypertension at the

time of seizures. In these cases, seizure may be a result of abnormal

autoregulatory response consisting of severe arterial vasospasm with rupture of

vascular endothelium and pericapillary hemorrhage. This may lead to

development of foci of abnormal electrical discharge that may cause

convulsions11.

4

The practical implication of these ideas is that the dose and duration of

antihypertensive to be given in preeclampia for prevention of elampsia remains

controversial.

Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4) is the most widely accepted agent for treatment and

prophylaxis of eclamptic seizure. The largest trial conducted so far viz. the

Magpie Trial shows that magnesium sulfate is the drug of choice for seizure

prophylaxis in preeclampsia.

Despite the widespread use of magnesium sulfate, its mechanism of action is not

clear. Magnesium sulfate is given intravenous or intramuscular and requires

specialized nursing training and monitoring to minimize toxicity from respiratory

and cardiac depression. In addition, patients often require an additional

antihypertensive agent. An ideal drug may be one which can be orally

administered, requiring less rigid monitoring and can be given in low resource

settings.

Labetalol,a combined and block is know to reduce CPP in women with

preeclampsia10. It acts by reducing the peripheral vascular resistance with little or

no effect on cardiac output. The potential advantages of using this drug for

treatment of acute severe preeclampsia and for maintaining treatment of

hypertensive disorders include: its effectiveness, low incidence of side effects

and availability of oral and parenteral preparation. Patients who might not

otherwise received seizure prophylaxis with magnesium sulfate due to logistic,

personnel, safety or training issues, will be in position to have treatment started

earlier. If labetalol is proven to be at least as effective as magnesium sulfate,

there will be a simplicity of the management of severe preeclmapsia with a

significant saving in terms of cost and time to reach a tertiary level care.

The current study is a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the role of labetalol

in prevention of eclampsia in women with severe pre-eclampsia.

5

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Hypertensive disorders during pregnancy form one of the deadly triad along with

hemorrhage and sepsis that contributes greatly to maternal morbidity and

mortality.

The pathophysiology of eclampsia is not known but it is thought to involve

cerebral vasospasm leading to ischemia, disruption of blood-brain barrier and

cerebral edema. Magnetic resonance imaging and Doppler data suggest that

overperfusion of the cerebral tissues is a major etiologic factor1,8. Hypertensive

encephalopathy6 from overperfusion, and vascular damage from excessive

arterial pressure (cerebral barotraumas) are believed to lead to vasogenic and

cytotoxic cerebral edema11, with resultant neuronal anomalies, seizure activity

and cerebral bleeding if left unchecked. Doppler studies have shown that

cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP)

is abnormally increased in severe

preeclampsia and that autoregulation of the middle cerebral artery is affected by

this condition leading to increased CPP.

Commonly used antihypertensive drugs in preeclampsia include labetalol,

hydralazine, nifedipine, nimodipine and for hypertensive emergencies IV

hydralazine, IV labetalol, nifedipine and sodium nitroprusside. According to the

Cochrane database review (2002), all these drugs have been found to be equally

efficacious12. Anticonvulsant therapy is recommended in the management of

severe pre-eclampsia to prevent seizures, and in eclampsia to prevent

recurrence of seizures. The evidence to date confirms the efficacy of magnesium

sulfate in reducing seizures in women with eclampsia and severe preeclampsia.

However, this benefit does not affect overall maternal and perinatal mortality and

morbidity.

A Multinational Eclampsia Trial Collaborative Group (1995) study involved 1687

women with eclampsia who were randomly allocated to different anticonvulsant

6

regimens13,14 and found magnesium sulfate to be superior to diazepam and

phenytoin in prevention of eclampsia. Superiority of magnesium sulfate therapy

over phenytoin was also shown by a study conducted by Lucas et al (1995)14. 10

of 1089 women randomly assigned to phenytoin regimen had eclamptic seizures

compared with no convulsions in 1049 women given magnesium sulfate

(p=0.004).

A randomized controlled trial conducted by Coetzee et al15 (1998) concluded that

the use of magnesium sulfate in management of women with severe preeclasmpsia significantly reduced the development of eclampsia.

The largest ever trial conducted till date, a multicentric randomized, placebo

controlled trial for anticonvulsants, The Magpie Trial7 (Magnesium sulfate for

Prevention of Eclampsia) in 175 hospitals in 33 countries worldwide enrolled

10,141 women with preeclampsia. The trial concluded that women who received

magnesium sulfate were 58% less likely to progress to eclampsia than those who

received placebo. In addition, these women were 45% less likely to die during

childbirth. There was no difference between the two groups in the risk of newborn

death.

Although the exact mechanism of action of magnesium sulfate is not known, the

proposed mechanisms include its cerebral vasodilatory effect (particularly on

small vessels)16, neuromuscular blockade as well as central action by means of

blocking cerebral N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors17.But it does not have

any antihypertensive action.

Despite the beneficial effects of magnesium sulfate, it is not an innocuous drug

and requires careful monitoring and affects many maternal and fetal

parameters18. In the mother it can cause flushing, sweating, hypotension,

depressed reflexes, flaccid paralysis, hypothermia, circulatory collapse, cardiac

and CNS depression proceeding to respiratory paralysis which mostly occur due

7

to administration errors. However the benefits of magnesium sulfate therapy

outweigh its potential risks in. Studies have shown that it does not increase the

duration of labor16, maternal blood loss, or caesarean section rate 17, Pruett et al

(1988) found no significant effects on neonatal Apgar scores at the doses of

magnesium sulfate currently in use for seizure prophylaxis19. Many institutions in

developing world lacks lack the necessary expertise to administer the medication

and many preeclamptic patients thus do not receive magnesium sulfate prior to

their first seizure. Given the risks of magnesium sulfate, it is possible that the use

of labetalol may be a safe alternative.

Mahmoud et al20 (1993) prospectively studied the effects of oral labetalol therapy

in patients with blood pressure range 140-150/100-105 mmHg. They concluded

that labetalol is an effective drug in controlling blood pressure and does not

adversely affect umbilical artery flow velocity waveform (UAFVW). It allows safe

prolongation of pregnancies complicated by PIH with a satisfactory fetal

outcome.

ACOG in 1996 recommended labetalol as one of the first line antihypertensive

medication for preeclampsia21.Labetalol, a combined and blocker, has been

used for many years to safely treat hypertension in preeclamptic women. It is a

competitive antagonist of 1 and 2 adrenoreceptors. In humans, the ratio of

and blockade are estimated to be approximately 1:3 and 1:7 for oral and IV

compounds respectively. It lowers the high blood pressure by blocking 1

adrenoreceptors in the peripheral vessels,

thereby reducing peripheral

resistance. Its blockade predominates during IV administration, which prevents

reflex increase in heart rate, cardiac output and myocardial oxygen consumption.

In preeclampia, it rapidly reduces blood pressure without decreasing the

uteroplacental blood flow. It crosses placenta but neonatal bradycardia and

hypoglycemia are rarely seen. Its disadvantages in preeclampsia include interpatient variability in dose requirement and variable duration of action 10. It has

been used both IV and orally for rapid reduction in BP. The Working Group of

8

NHBPEP (2000) recommends starting with a 20 mg IV bolus dose in severe

preeclampsia. If not effective within 10 min, this is followed by 40 mg, then 80 mg

every 10 min, but should not exceed a total of 220 mg per episode. However a

dosage frequency of 20 min with a maximum of 300 mg has also been found to

be equally effective30.The onset of action of IV labetalol is within 5 min and peak

effect is reached within 10-20 min. The peak serum level of labetalol occurs

within 20-60 mins with an elimination half life of 1.7±0.27 hours22. The elimination

half life after intravenous administration in pregnant hypertensive patients is

similar to that seen with oral administration23. The oral dose is 100 mg which can

be increased to 400 mg BD with maximum of 1200 mg/day. The maintenance

dose is usually 200-400 mg BD.

Oral labtetalol has been used for acute control of severe pre-eclampsia and has

been found to be comparable to parenteral hydralazine21. A meta-analysis of

trials revealed that labetalol was no more effective than hydralazine or diazoxide

in decreasing severe hypertension. However, labetalol was associated with less

maternal hypotension, smooth blood pressure control and fewer cesarean

sections. In terms of fetal effects, blood pressure reduction with labetalol did not

result in fetal distress unlike acute BP reduction with hydralazine where 15% of

fetuses exhibited distress requiring immediate cesarean24,25,26. Labetalol also has

antiplatelet aggregation action27, a thromboxane reducing effect28, and fetal lung

maturation accelerating influence29. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled

trials using hydralazine for treatment of severe hypertension does not support the

use of this agent as first line drug when compared with labetalol and nifedipine.

A randomised double blind trial conducted by Vermillion et al30 (1999) to compare

the efficacies of oral nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker and intravenous

labetalol in acute management of hypertensive emergencies of pregnancy

concluded that both are equally effective in management of acute hypertensive

emergencies

of

pregnancy.

However

nifedipine

was

found

to

control

hypertension more rapidly and was associated with a significant increase in

9

urinary output. A study conducted by Belfort et al (2003)8 to compare magnesium

sulfate and nimodipine, a calcium channel blocker with cerebral vasodilatory

effect, for prevention of eclampsia concluded that women who received

nimodipine were more likely to have eclampsia (0.8% versus 2.6%).

Labetalol reduces the cerebral perfusion pressure while maintaining the cerebral

blood flow10. It is potentially an ideal agent for preventing eclampsia which is

believed to be the result of cerebral overperfusion.

Data reported by Walker et al31 over a 10 year period, show the rates of seizures

with labetalol is 1 in 455 (0.2%) in approximately 36000 pregnancies with a 10%

rate of hypertension during pregnancy. Inspired by the above study, LAbetalol

versus Magnesium Sulfate for the Prevention of Eclampsia Trial (LAMPET) was

planned. Labetalol may be a viable alternative to magnesium sulfate for the

prevention of eclampsia as suggested by preliminary data for first 202

participants

in

the

LAMPET

an

international,

multicentral,

non-blinded

randomized controlled trial.

The use of labetalol, which is more specific in mechanism of action, less toxic

agent, which can be administered orally, may simplify the management of severe

preeclampsia. In addition, the facility of administration and reduced risk of

respiratory and cardiac depression, lack of need of intensive monitoring and low

cost of regimen gives labetalol an attractive risk-benefit and cost-benefit ratios.

The drug requires investigations in developing countries as well to establish the

safety and efficacy in population which probably suffers the most from

hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and its complications.

Lacunae in existing knowledge:

Precise intervention for seizure prophylaxis in severe pre-eclampsia is still

unclear

10

Universally accepted regimen of magnesium sulfate requires considerable

training and expertise in administering the drug and rigid monitoring

protocols which are not feasible in many low resource settings in

developing countries like India

Magnesium sulfate regimen also requires an additional antihypertensive

agent

Documentation of the efficacy of an antihypertensive agent which can be

given orally and also brings about prevention of seizures with equal

efficacy as magnesium sulfate would be highly desirable

11

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

Aim

Evaluation of Labetalol in prevention of eclampsia in patients with severe preeclampsia

Objective

1.

To evaluate the effect of labetalol in prevention of eclampsia in patients

with severe preeclampsia.

2.

To compare the efficacy of labetalol with magnesium sulfate regimen in

prevention of eclampsia in patients with severe preeclampsia.

12

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design: A prospective, randomized, comparative clinical trial with active

control.

Study setting: A total of 60 patients with severe preeclampsia either in labour or

requiring termination of pregnancy admitted in the Department of Obstetrics and

Gynaecology, Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital and University College of Medical

Sciences, Delhi will be enrolled in the study from November 2009-April 2011. A

clearance from ethical committee will be taken.

Inclusion Criteria

1 Systolic blood pressure 160mm Hg and diastolic 110mmHg with any

proteinuria (≥300mg/dl or ≥1+ on dipstick)

2 Blood pressure of any range with at least one of the following

a) proteinuria (≥2+ on dipstick or ≥5 g/24 hour urine collection)

b) Persistent frontal headache.

c) Visual or cerebral disturbances.

d) Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain.

e) Persistent clonus and/or hyperreflexia

f) HELLP syndrome - Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes (LDH >600 U/l,

AST ≥70 U/l), low platelet (<100 x 109/l) or partial HELLP syndrome

consisting of only one or two elements of the above triad.

Exclusion Criteria

1. Eclampsia.

2. Deranged renal functions (urine output <100 ml/4 hour, urea >10 mmol/l

3. Pulmonary edema

4. Imminent LSCS indication

5. Received antihypertensive agent within 6 hours prior to enrollment

6. Already on magnesium sulfate

13

7. Known case of myasthenia gravis

8. Known hypersensitivity to magnesium

9. Refusal or inability to obtain informed consent.

Consent

All patients selected for the study will be explained about the trial. Written

informed consent (Annexure-1) will be taken.

Pre treatment workup (Annexure-2)

History

A detailed history with specific reference to period of gestation, duration

and onset of labour, time of rupture of membranes in patients in labour

and symptoms of impending eclampsia.

Examination

General physical examination – in particular blood pressure, respiratory

rate, presence of deep tendon reflexes, edema and cyanosis

Systemic examination

Obstetric examination to assess the route of delivery

Recording of BP

Women should be seated or lying at 45° with arm at level of heat

Mercury sphygmomanometer with appropriate sized cuff will be used

Phase-V of Korotkoff sound will be taken as the measure of DBP, when

phase V is absent phase IV (muffling) will be accepted

Investigations

Haemogram with platelet count

Peripheral smear for hemolysis

Urine albumin (by dipstick analysis)

Blood urea, serum creatinine, serum electrolytes

14

Coagulation profile: Prothrombin time (PT), Partial thromboplastin time

(PTTK)

Liver function tests (Serum bilirubin, AST, ALT,LDH)

Ophthalmological examination of fundus

Routine antenatal investigations - blood grouping, Rh typing, voluntary

councelling test for HIV,VDRL etc., if not already done

Randomization of Patients

After the initial workup, randomization will be done using computer generated

random numbers to one of the two treatment groups –

Group A: Labetalol group (study group)

Group B: Magnesium sulfate group (control group)

Intervention

Group A (labetalol group)

According to the mean arterial pressure (MAP), patients will be given either oral

or intravenous (iv) labetalol loading dose

MAP 125 mmHg- 20 mg iv , with repeat dose of 40 mg, 80 mg, 80 mg given

every 20 min till BP < 150/100 mmHg or a maximum of 5 doses after which

Nifedipine will be given as per in group B.

MAP <125 mmHg- Patients will receive 200 mg oral labetalol

Maintenance dose: irrespective of whether loading dose was iv or oral, a dose of

200mg labetalol every 6 hours from the time of inclusion in the study will be

given.

Patients developing eclamptic seizures will be given therapeutic magnesium

sulfate regimen as in group B.

15

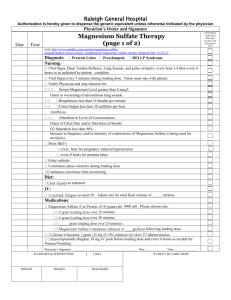

Group B (magnesium sulfate group)

Patients will receive 4 gm of magnesium sulfate as a 20% solution loading dose

slow iv followed by magnesium sulfate 5 gm of 50% solution deep

intramuscular(IM) in upper outer quadrant of both buttocks and maintenance

dose of 5 gm in 50% solution deep IM in alternate buttock every 4 hour after

ensuring:

1) Patellar reflex is present

2) Respiratory rate >14/min

3) Urine output in previous 4 hrs exceeds 100 ml

Patients with MAP ≥125 mmHg will receive Nifedipine 10 mg oral capsule in

incremental doses repeated every 20 min until DBP<100mmHg and SBP<150

mmHg or a maximum of 5 doses. If BP is still not controlled labetalol will be given

as in group A.

In both the groups requirement of postpartum antihypertensive therapy will be

assessed based on the blood pressure levels.

Obstetric Management

Induction of labour where indicated will be done as per standard protocol

based on Bishop score

Maternal and fetal monitoring along with monitoring of progress of labour

will be carried out as per norms of management of any high risk

pregnancy (Annexure-3)

Cesarean section, under appropriate anaesthesia will be performed where

indicated and the anaesthetist will be informed about the medications.

Presence of pediatrician will be ensured for all cases

Cord blood sugar levels will be taken after delivery of placenta

OUTCOME MEASURE

Primary outcome measure

1. Occurrence of eclamptic seizure(s) after enrollment in the study.

16

Secondary outcome measures

Maternal

1. Need for additional antihypertensive medication

2. Subjective assessment of side effects by the patient.

3. Objective assessment of new onset complications and/or side effects by

the treating clinicians

4. Labor and delivery parameters including induction to delivery interval

Fetal and neonatal outcome

1. Intrapartum fetal distress

2. 5 min Apgar score

3. Any neonatal complication

DATA ANALYSIS

Data analysis will be done using SPSS software (version 17).

Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test will be used for categoric variables and

Student’s t-test for continuous variables. p<0.05 will be considered significant.

17

REFERENCES

1.

Hypertension

in

Pregnancy,

ACOG

Technical

Bulletin

No.

219,

Washington DC: The College; 1996: 1-8.

2.

NHBPEP Working Group on High Blood Pressure. Report of NHBPEP

Working Group in Hypertension in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;

183: S1-22.

3.

Diagnosis and management of preeclampsia and eclampsia. Practice

bulletin No.33.Washington DC: Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2002.

4.

Hauth JC, Ewell MG, Levine RJ, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in healthy

nulliparas who developed hypertension. Obstet Gynecol 2000; 95: 24-8.

5.

Sibai BM, Mercer BM, Schiff E, et al. Aggressive versus expectant

management of severe preeclampsia at 28-32 weeks gestation: a

randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 171: 818-22.

6.

Belfort MA, Varner MW, Dizon-Townson DS, Grunewald C, Nisell H.

Cerebral perfusion pressure, and not cerebral blood flow, may be the

critical determinant of intracranial injury in preeclampsia: A new

hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 187: 626-34.

7.

Altman D, Carroli G, Duley L. Do women with preeclampsia and their

babies benefit from magnesium sulfate? The Magpie Trial: a randomized

placebo controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359(9321): 1877-90.

8.

Belfort MA, Anthony JA, Saade GR, Allen JC. Magnesium sulfate versus

nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 30411.

9.

Belfort MA. Is CPP and cerebral flow predictor of impending seizures in

preeclampsia? A case report. Hypertens Preg 2005: 24(1): 59-63.

10.

Belford MA, Tooke-Miller C, Allen JC Jr, Dizon-Townson D, Warner MA.

Labetalol decreases cerebral perfusion pressure without negatively

affecting cerebral blood flow in hypertensive gravidas. Hypertens Preg

2002; 21(3): 185-97.

11.

Cunningham FG, Lindeimer MD. Hypertension in pregnancy: Current

18

concepts. N Engl J Med 1992; 326: 927-30.

12.

Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ. Drugs for treatment of very high blood

pressure

during

pregnancy.

Cochrane

Database

Sys

Reb

2002;(4):CD001449.

13.

Eclampsia Trial Collaborative Group. Which anticonvulsant for women

with eclampsia? Evidence from the collaborative eclampsia trial. Lancet

1995; 345: 1455-63.

14.

Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. A comparison of magnesium

sulfate with phenytoin for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med 1995;

333: 201-8.

15.

Coetzee EJ, Dommisse J, Anthony J. A randomised controlled trial of

intravenous magnesium sulphate versus placebo in the management of

women with severe pre-eclampsia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 105: 3003.

16.

Michael A, Belfort MA, Moise KJ. Effect of magnesium sulfate on maternal

brain blood flow in preeclampsia. A randomized placebo controlled study.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 167: 661-6.

17.

Gambling DR. Hypertensive disorders. In: Chestnut DH, ed. Obstetric

Anaesthesia: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed. Mosby; 2004: 794-837.

18.

Katz VL, Farmer R, Kuller JA. Preeclampsia into eclampsia. Towards a

new paradigm. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 182: 1389-96.

19.

Pruett KM, Krishon B, Cotton DB, et al. The effects of magnesium sulfate

therapy on Apgar scores. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 159: 1047-8.

20.

Mahmoud TZ, Bjornsson S, Calder AA. Labetalol therapy in pregnancy

induced hypertension: the effects on fetoplacental circulation and fetal

outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1993; 50(2): 109-13.

21.

Management of Preeclampsia, ACOG Technical Bulletin, No. 219,

February,

1996.

The

American

College

of

Obstetricians

and

Gynecologists. Washington, DC.

22.

Rogers RC, Sibai BM, Whybrew WD. Labetalol pharmacokinetics in

pregnancy-induced hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynacol 1990; 162: 362-6.

19

23.

Rubin PC, Butters L, Kelman AW, Fitzsimons C, Reid JL. Labetalol

disposition and concentration-effect relationships during pregnancy. Br J

Clin Pharmacol 1983; 15: 465-70.

24.

Spinnato TA, Sibai BM, Anderson GD. Fetal distress after hydralazine

therapy for severe PIH. South Med J 1986; 79: 559-62.

25.

Michael CA. Use of labetalol in treatment of severe hypertension during

pregnancy. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 8: S211-5.

26.

Riley AJ. Clinical pharmacology and labetalol in pregnancy. J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol 1981; 3: S53-9.

27.

Greer IA, Walker JJ, McLaren M, Calder AA, Forbes CD. A comparative

study of the effects of adrenoreceptor antagonists on platelet aggregation

and thromboxane generation. Thromb Haemost 1985; 54: 480-4.

28.

Greer IA, Walker JJ, Maclaren M, Calder AA, Forbes CD. Inhibition of

thromboxane and prostacyclin in whole blood by adrenoreceptor

antagonists. Prostaglandins Leukotrienes Med 1985; 19: 209-17.

29.

Michael CA. Early fetal lung maturation associated with labetalol therapy.

Singapore J Obstet Gynaecol 1980; 11: 2-5.

30.

Vermillion ST, Scardo JA, Newman RB, et al. A randomized double blind

trial of oral nifedipine and IV labetalol in hypotensive emergencies of

pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999; 181: 858-61.

31.

Walker JJ. Preeclampia. Lancet 2000; 326: 1260-5.

20

ANNEXURE-1

INFORMED CONSENT FORM

I _______________________ am willing to enroll myself in the study titled

“EVALUATION OF LABETALOL AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO MAGNESIUM

SULFATE IN THE PREVENTION OF ECLAMPSIA”. I give my full free and

voluntary consent for examination, any intervention and publication.

I also give my voluntary consent to be enrolled in either treatment group (drug or

placebo as the case may be) depending upon the randomized allocation.

Signature / thumb impression

of patient

Signature / thumb impression

of witness

Date

Doctor’s signature

®úÉäMÉÒ EòÉ ºÉ½þ¨ÉÊiÉ {ÉjÉ

¨Éé ………………………………………… +{ÉxÉÒ º´ÉäSUôÉ ºÉä

ÊSÉÊEòiºÉEòÒªÉ

+vªÉªÉxÉ

¨Éå

+{ÉxÉä

+É{ÉEòÉää

ºÉΨ¨ÉʱÉiÉ Eò®úxÉä EòÒ ºÉ½þ¨ÉÊiÉ |ÉnùÉxÉ Eò®úiÉÒ

½ÚÄþ*

¨ÉÖZÉä

ºÉä´ÉÉ

|ÉnùÉxÉ

Eò®úxÉä

´ÉɱÉä

ÊSÉÊEòiºÉEò xÉä ¨ÉÖZÉä ºÉÆiÉÖι]õ EòÒ ºÉÒ¨ÉÉ iÉEò

<ºÉ ÊSÉÊEòiºÉEòÒªÉ +vªÉªÉxÉ EòÒ |ÉEÞòÊiÉ ´É =qäù¶ªÉ

ºÉä ¦É±ÉÒ ¦ÉÉÆÊiÉ +´ÉMÉiÉ Eò®úÉ ÊnùªÉÉ ½èþ*

®úÉäMÉÒ Eäò ½þºiÉÉIÉ®ú MÉ´Éɽþ Eäò ½þºiÉÉIÉ®ú

21

+lÉ´ÉÉ +ÄMÉÚ`äö EòÉ ÊxɶÉÉxÉ +lÉ´ÉÉ +ÄMÉÚ`äö EòÉ

ÊxɶÉÉxÉ

ÊSÉÊEòiºÉEò Eäò ½þºiÉÉIÉ®ú

ÊnùxÉÉÆEò

22

ANNEXURE-2

CASE RECORD FORM

Case no.

CR no.

Date:

Date of admission:

Name:

Age:

Address:

Phone no:

Religion:

Booked/unbooked:

SE status:

Dietary history:

Antenatal medications: Haematinics, calcium supplementation

History

Menstrual history

LMP

EDD

POG

Obstetric history

Any specific complaints

Headache

Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain

Visual symptoms

Decreased urinary output

Respiratory distress

Edema

Convulsions

Others

Past history

Hypertension

Preeclampsia or eclampsia in previous pregnancy

Myasthenia gravis

23

Seizure disorder

Hypersensitivity to magnesium

Nature of treatment received

Family history

Examination

General physical examination

Vitals

Pulse rate

Blood pressure

Respiratory rate

Pallor / icterus / cyanosis / edema

Systemic examination

Respiratory

Cardiovascular

Per abdomen

Per vaginum

Bishop score

Investigations

Routine

Hb

BG

VDRL

GCT/GTT9glucose challenge test/ glucose tolerance test)

Urine routine :albumin, sugar,

Special

Hemogram with platelet count

24

Peripheral Smear for hemolysis

Urine albumin (by dipstick analysis)

Serum uric acid

Blood urea, Serum electrolytes, Serum creatinine

Coagulation profile

Liver function tests

Ohphthalmological examination of fundus

Details of neonate

Birth weight

Apgar score

Neonatal resuscitation

NICU stay

Neonatal morbidity / mortality

Condition at discharge

25

ANNEXURE-3

PARTOGRAPH

26