(Dynak, Whitten, Dynak,1997).

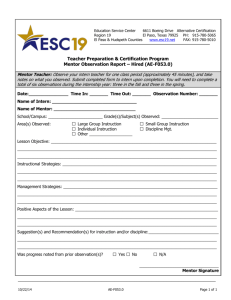

advertisement

AUTHOR: Janet Dynak; Elizabeth Whitten; David Dynak TITLE: Refining the General Education Student Teaching Experience through the Use of Special Education Collaborative Teaching Models SOURCE: Action in Teacher Education v19 p64-74 Spr '97 The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in violation of the copyright is prohibited. AUTHOR ABSTRACT Reform efforts in teacher education have established school-university partnerships that link teachers' professional development with preservice preparation in order to merge more forcefully educational theory and practice. Collaborative approaches, developed to facilitate the work of classroom teachers and special education teachers can be of great help to general education student teachers and their mentors who teach in professional development school settings. These authors define specific collaborative teaching approaches for student teachers and mentors to enable them to make more informed decisions about how and when to use collaborative teaching experiences to better meet the needs of their P-12 students. We examine models of collaborative teaching and relate them to the shared roles of mentors and student teachers in designing, communicating, and monitoring instruction. We also include examples of how these models work in elementary and secondary classrooms. Over the past 30 years, theorists, administrators, practitioners, and program developers working within the field of special education have moved--at times forcefully, at times reluctantly--toward inclusion and away from isolation of students with special needs (York & Reynolds, 1996). Such a move has created the need for an array of models that redefine the roles of classroom teachers and special education resource personnel in order to meet more effectively the needs of a diverse population of learners (Nevin, Villa, & Thousand, 1992). Thus, historically prominent, "traditional" approaches toward serving students with special needs characterized by one educator working with a group of students--often in self-contained settings-have given way to collaborative teaching (co-teaching) approaches that are characterized by a sharing of responsibilities between classroom teachers and special education teachers. They are asked to work together on instructional planning, delivery, and mutual, ongoing professional development in classrooms where students are heterogeneously grouped (Meyers, Gelzheiser, & Yelich, 1991). The strength of collaborative teaching--particularly as seen through the lenses of school reform and restructuring initiatives--is that it allows general and special education teachers to be more responsive to the needs of students as they interact and relate past and present experiences to construct meaning (Dewey, 1916; Vygotsky, 1978). The importance of staff development to promote the efficacy of co-teaching models to meet the needs of students with disabilities in the general education classroom, as well as the changing needs of classroom teachers and special education teachers, has been well established (Bauwens & Hourcade, 1995; Friend, Reising, & Cook, 1993; Redditt, 1991; Villa & Thousand, 1992; Walther-Thomas & Carter, 1993). Several approaches to collaborative teaching have been identified in the literature. Recurrent labels for these co-teaching approaches include complementary teaching, parallel teaching, station teaching, alternative teaching, and team teaching. Working within these approaches, the general education teacher and the special education teacher form a team to provide instruction to a heterogeneous group of students. Through intentional, collaborative efforts between the general and special education teachers, students with disabilities can purposefully be placed with students without disabilities to make teaching and learning more meaningful for all. The argument presented here is that collaborative approaches intended to facilitate the work of classroom teachers and special education teachers can also be of great help to general education preservice teachers and their classroom teacher/mentors--particularly in making decisions about how teaching and learning practices can be implemented by planning shared experiences. Our sense is that teaching should not be an isolated act. Thus, all teachers should collaborate with other general education teachers, special education teachers, and content-area specialists as a normal part of their school day. Using co-teaching approaches during the student teaching semester could provide crucial practice time in this arena for student teachers and their mentors at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. Additionally, emerging from the dialogue on school reform and restructuring, many teacher education programs have formed partnerships with P-12 schools to link field experiences of preservice teachers to a school-based model of self-renewal developed by classroom teachers and university faculty (Farris, Henniger, & Bischoff, 1991). As a result of these partnerships, the traditional boundaries for professional development of preservice teachers--which often confined the focus of evaluation to the preservice teacher's ability to deliver content independently to a group of students--have been broadened. There is a need for educators to be interdependent and make use of each other's knowledge about teaching and learning (Lieberman, 1995). Professional development school initiatives have created mergers that seek to cultivate sites where systemic reform can proceed, and (hopefully) flourish (The Holmes Group, 1986). In many P-12 schools where a partnership with a teacher education program has been established, classroom teachers work with one or more student teachers each semester. At an increasing number of sites, university faculty, classroom teachers, and student teachers are attempting to share power while constructing knowledge about teaching (Feiman-Nemser, 1992). CochranSmith (1991) defines this approach to student teaching as one where preservice teachers connect what they learn from their university communities that are engaged in constructing and actualizing a collaborative ethos. In these sorts of contexts, the roles of teachers who supervised the preservice teachers are expanded. Thus, rather than simply serving as models of best practice and evaluators of the abilities of student teachers to approximate what is modeled, these teachers become mentors, and the student teachers become interns. The university faculty become facilitators who support and work within this organizational structure. A hallmark of mentoring is self-study. Thus, mentors study their teaching practices as they offer clinical supervision to their interns (Odell, 1990). Mentors and interns are encouraged to establish a trusting relationship where decisions about designing, communicating, and monitoring instruction can be shared. An example of how one teacher education program has attempted to focus that relationship can be found in The Mentor Teacher Handbook developed by the College of Education at Western Michigan University (1995). This handbook refers to decisions about instruction as the Cycle of Teaching Practices (see Figure 1). In this model, mentors and interns design instruction to maximize student learning. In addition, decisions regarding rules and procedures that will govern movement, interaction, and access to content resources and materials are collaboratively developed. Mentors and interns inform students about the way communication will occur and reinforce the message through role-taking, explanation, practice, and feedback. Monitoring includes surveying events and student interactions through self, peer, intern, and mentor assessments to make sure the teaching and learning processes are working and changing in appropriate ways. In this mentor/intern relationship, regular reflection-- by interns and mentors--that analyzes teaching practices through the use of critical and creative problem-solving strategies is crucial for making deliberate decisions about future teaching episodes. Ideally, mentors guide intern teachers through a gradual series of situations that build on their reflections and demonstrated abilities. General education interns and mentors often use the term "team teaching" to refer to any joint instructional experience. However, this generalized use of the term by mentors and interns may impede exploration of collaborative teaching options. Defining specific collaborative teaching approaches for use by general education mentors and interns may enable them to make informed decisions about how and when to use collaborative teaching experiences to better meet the needs of the P-12 students with whom they work. We will describe and examine how collaborative teaching can be conceived and implemented by general education interns and mentors. To do this, we have used the special education literature on approaches to collaborative teaching as our starting point. However, we have taken some liberties with these approaches. First, we have purposefully labeled the various coteaching practices as "models" to allow for more specificity than is implied by the term "approaches." We spell out the roles and responsibilities of co-teachers when using these practices. Second, in order to avoid ambiguity and circumvent a problematic hierarchy--with "team teaching" often characterized in the literature as the approach of best co-teaching practice, and other approaches as somewhat lesser forms of team teaching--we have replaced the term "team teaching" with "shared teaching," and represented the models in a non-hierarchical way. Thus, five discrete, coequal models of co-teaching have been constructed--complementary teaching, parallel teaching, station teaching, alternative teaching, and shared teaching. We acknowledge that, in tightening the definitions of these models, we may have changed the ways in which these approaches tend to be conceived by some special education theorists. However, viewing the models as a palette of options, rather than as a hierarchy, may provide a more powerful image to guide mentors and interns as they structure classroom events. COMPLEMENTARY TEACHING Complementary teaching can be used when it would benefit the P-12 students to have a teacher model self-regulated learning during the lesson. In addition, this model can be used by teachers to facilitate metacognition when students are completing an assignment after a lesson has been delivered. Complementary teaching allows the mentor an opportunity to model content instruction while the intern provides strategy instruction to students who are having difficulty comprehending the content and/or the tasks of the lesson. Many mentors loosely implement this model when they ask interns to walk around and "assist" or "help" students during or after a lesson that is taught by the mentor. However, when the kinds of "help" are not explicitly stated, the new intern does not know which strategies to use nor how much assistance to provide to a given student or group of students. In order to implement this model more effectively, the mentor and the intern must review the material to be presented and identify areas that require students to use metacognitive skills to complete a given task. The mentor can then offer suggestions to the intern on ways to present an instructional strategy or model the techniques that will promote comprehension of the lesson content. Depending on the age level of the students and the tasks assigned, strategies such as note-taking, concept mapping, summarizing, memorizing, activating prior knowledge, modeling additional examples to clarify content, and/or organizing the steps of an assignment might be used by the intern to assist individuals or small groups of students. Sometimes, when several students are having difficulty with a given task such as note-taking, the intern can model one method of taking notes to the whole class while the mentor presents the content. The intern might use the overhead projector to demonstrate a given note-taking strategy that would help the students use the content at a later time. Near the beginning of the intern teaching experience, the complementary teaching model offers the intern the opportunity to understand the mentor's thinking about the content and instructional design of a lesson and the skills needed by the students to complete the related tasks. The intern is more directly involved in communicating the strategy portion of the lesson. In addition, the intern can observe the instructional techniques that the mentor uses when delivering the content of the lesson. The intern and mentor both monitor the lesson. As the intern becomes more experienced, the roles of the co-teachers can be reversed. Thus, the intern might design and present the content of the lesson, while the mentor provides the strategy instruction or content support. This allows the mentor to observe the intern while the students benefit from having both teachers actively involved in the lesson. When designing a lesson, the interns have the opportunity to reflect about their own skills and ask for assistance in areas where they feel they may need support. When the lesson has been planned and discussed prior to implementation, the mentor can "step in" and complement the lesson without it being taken as a corrective interruption. The following example will describe how this model was employed in a given classroom context. Since the roles of the mentor and intern may reverse during the course of the field experience, the cycle of teaching responsibilities for each of the co-teachers using the complementary model (as well as the other models) will be identified using the titles of lead teacher and support teacher. EXAMPLE: SECONDARY HEALTH A lead teacher was giving a series of lectures and demonstrations on drug abuse. As part of the objectives for the lessons, the students were required to take notes for future reference. The support teacher modeled note-taking teachniques using an overhead projector so all students could see how notes could be taken. Students having difficulty with note-taking had the opportunity to follow the lead of the support teacher during the lecture. For each lecture and demonstration, a discrete note-taking strategy was modeled. Thus, one lecture was structured in a hierarchical format, and the support teacher modeled a formal outline. During a lecture that identified new terminology, the support teacher modeled a three-tiered note-taking technique which allowed students to view three different columns--one column for basic information, a second column for key terms, and a third columns for examples and questions. When the lecture information became more fluid, a concept map was explored for its usefulness. After the lectures, the support teacher worked with students who needed further assistance. For these students, the support teacher provided a quick review of the content and note-taking strategy (e.g., reviewing the main points, highlighting important concepts and terms listed from the lecture notes, helping students organize their thinking). STATION TEACHING Station teaching can be used when students need to work in small groups to complete a variety of tasks that help promote the learning of specific content. This model allows the intern teacher and the mentor to divide the content of the lesson between them. Often, lessons that involve station teaching are taught over the course of several days. Station teaching can be directed toward individual and/or small group instruction. In most cases the students are placed into groups, and they work with each teacher on specific components of the lesson. Some students may need to work individually, and this model allows teachers the opportunity to plan for each student. The mentor and the intern collaboratively design and organize the lesson content and make decisions about their roles and the experiences students will have at the various stations. Initially, the intern designs, communicates, and monitors the specific part of the lesson plan for one or two stations. As the intern becomes more competent, additional stations can be added to the intern's teaching load. Eventually, the mentor may be responsible for only one station, while the intern assumes the lead role with the other stations. This model allows for several teachers to be involved in one lesson without undue confusion. This creates a learning environment where multiple activities that promote inquiry can take place at the same time. It also allows for compiling and navigating extensive resources that a single teacher would not have time to accomplish alone. As a result, this model works well in situations where interns are paired and placed with one mentor or where an intern joins an existing team of teachers who jointly work with a given group of students each day. EXAMPLE: ELEMENTARY SCIENCE UNIT ON PLANTS AND PEOPLE AS PARTNERS Station one. The station teacher collected narrative, expository, and atypical texts and set up an area where a small group of students researched how the seasons affected people and plants. Students gained information on the seasons through the study of various genres of texts. The students then created their own piece of text using the examples provided. Station two. The station teacher provides a short presentation about the purpose and types of plants used in landscaping. From this information, the students working at this station used gardening magazines, graph paper and colored pencils to draw a map of how they would landscape a given plot of land. They also described why their landscape design was useful to the people who would view and/or use the plot of land. Station three. The station teacher prepared an area in the classroom where students could research the ecological partnership between plants and people through comparing and contrasting the growth of seeds in soil and those grown without soil. Students in this station were paired. Between them, they decided who would sprout their seed in soil and who would sprout their seed on wet paper towel. The pairs of students selected their seeds and made written predictions about how the seeds would grow over the course of three weeks. Daily, each pair of students went to the station to care for the seeds, make observations, and record their findings. At the end of the three week period, the students compared their daily data and end results to the original predictions they made. Station four. Using three or four countries where students (or relatives of students) in the class had been born, the station teacher collected reference materials and set up an area where students could construct a relief map of the types of terrain found in the country they had chosen to study. The students then researched the country's resources and the related jobs people did. The students created factual or fictional stories based on the relationship among the terrain, resources, and jobs found in a given country. The support teacher videotaped the students as they read or acted out their stories with the help of their peers. PARALLEL TEACHING Parallel teaching can be used to reduce the student-teacher ratio so that each teacher is able to work more intensively with a smaller group of students. The class is divided into two groups. Each teacher (i.e., mentor and intern) acts as facilitator for one of the groups. Given the sizes of the groups, students have more opportunities to participate actively in the lesson, and to interact with each other and with their teachers; the mentor and intern have greater access to the ways learners engage themselves in the lesson. Although parallel teaching can work well for all lessons, this model is particularly well-suited to explorations of content that include small group discussion. Parallel teaching allows the mentor and the intern the opportunity to jointly design the full lesson. The intern has the opportunity to participate in the planning process while being supported by the mentor's knowledge of the content and past experiences with learners. And, the intern is able to facilitate and monitor the full lesson plan to a portion of the class. However, since the number of learners is reduced, the intern is able to attend more closely to how learners experience the content, and how the structure of the content tends to affect those experiences. While reflection is a key component to the cycle of teaching when using any co-teaching model, parallel teaching offers the mentor and intern a structure through which they can discuss planning options and reflect together about their individual experiences using the same lesson plan with a different group of students. The mentor demonstrates the reflection process--which includes the examination of the instructional decisions made during the implementation of the lesson and the sorts of self-evaluation that occur after the lesson. The mentor then guides the intern through the same self-reflective process. EXAMPLE: ELEMENTARY MATH The mentor and intern planned a lesson where the students applied their knowledge of how to find the area of a given space to a self-selected room in their home. In order for all students to have the opportunity to present a scaled drawing of a room in their home, and, working with a group of peers, find the area of the space, the teachers divided the students into two heterogeneneous groups. Each teacher facilitated one of the groups. Each teacher reviewed the steps necessary to compute the area of a given space with their group. Using the measurements and drawing of a room in their home, each student in the group was called upon to lead their peers through the steps to find the area of their room. Each teacher monitored the individual students as they led the discussion and problem-solving activity. In addition, the students monitored each other by writing down the information presented by each person in their group. ALTERNATIVE TEACHING Alternative teaching can be used when re-teaching or extension of the lesson content would benefit some or all of the students. In alternative teaching, tasks and activities are designed to supplement the key instructional content of the lesson. The lead teacher typically communicates the initial presentation of content while the support teacher monitors the class to identify those students who would benefit from alternative forms of instruction. The support teacher then creates additional components to make the content of the lesson more meaningful for those students, or develops multifaceted curriculum to address the needs of all students. Peer tutoring, cross-age tutoring, field trips, computer-assisted instruction, creative arts interventions, experiential educational programs, and guided inquires are examples of methods and approaches that can be used for alternative teaching. Many of these activities move the cycle of teaching practices beyond the boundaries of the traditional classroom and foster experimental approaches to instruction. Assessment of the students' learning styles, interests, intelligences (Gardner, 1993), and prior knowledge of the content can be used to make instructional decisions about how and when to use alternative teaching before or after the formal lesson. While it is understood that interns need to spend a great deal of time practicing the technical aspects of instruction, it must be recognized that a crucial part of the teaching cycle includes exploring ways to integrate alternative forms of pedagogy into various teaching/learning contexts. The alternative teaching model offers the intern the opportunity to develop a knowledge base that includes ways of designing, communicating, and monitoring enrichment and support activities for all lessons. EXAMPLE: SECONDARY WORLD HISTORY During a unit on World War II, the lead teacher taught a lesson which asked the students to read about the treatment of the Jewish people who lived in Europe during the war. After the students read orally from their textbook, the lead teacher showed photographs of concentration camps to generate discussion about the treatment of the Jewish people during the war. The support teacher observed the students during the lesson and noted that, while the students participated in the lesson and asked several good questions about the pictures, they appeared to lack a deep understanding of how this treatment could really have happened. Many commented that "It was so long ago" and had little to do with their lives today. The support teacher designed an alternative lesson where the students were asked to explore the Internet to find the home pages produced by some of the Jewish survivors of the concentration camps from World War II. After reading the information contained on the home page, the students identified questions they wanted to ask survivors about their treatment during the war and how that treatment affected them and others in the world today. Then the students were placed in small groups and each group wrote E-mail messages to a minimum of three survivors. The whole class discussed the information that was collected from the survivors. SHARED TEACHING Shared teaching can be used when whole group instruction is desired. The P-12 students benefit from observing a high level of collaboration where the content and pedagogical expertise of the two teachers is integrated into one lesson. Shared teaching is perhaps the most difficult to achieve. The model requires that both teachers equally share all components of the cycle of teaching practices. One teacher may assume the lead for parts of a lesson, but their roles are easily interchangeable as they intuitively or consciously reflect-in-action and try to make the lesson more meaningful to the students. The teachers jointly plan the lesson and negotiate the format of the presentation. Both teachers engage in an ongoing dialogue about the content of the lesson while also attempting to involve all the students. They must demonstrate turn-taking, question-asking, and effective communication. One teacher may take the lead introducing information to students while the other teacher follows up with additional information or explanation by paraphrasing the first teacher, asking questions of the lead teacher that anticipate students' difficulties, and probing students for their responses to the content. Teachers must have strong interpersonal skills and mutual trust of one another to employ shared teaching. While both teachers plan the lesson, lead teacher and support teacher roles are fluid and changeable. Since shared teaching requires teachers to spontaneously react to each other and to their students, it may not be possible for all teachers to collaborate to this extent. When the mentor and the intern do not have similar teaching styles or the intern needs to focus on specific components of the teaching cycle, it may not be a model that can be used extensively during the intern teaching semester. EXAMPLE: SECONDARY AMERICAN LITERATURE In their literature class, the students were in the midst of a unit which included reading excerpts from the biographies of Abigail Adams and Thomas Jefferson. The students read the passages so that they could discuss how the sections of the biographies related to the time period and historical events that were taking place. Working collaboratively, both teachers designed a lesson where one assumed the role of Abigail Adams, and the other the role of Thomas Jefferson. They began the lesson by each giving a summary of their biography and the beliefs that they had about the events of their time period. Then, the students were asked to develop questions for the characters. During the question/answer period, the teachers moved in and out of character as they answered the students' questions and attempted to provoke debate about the controversial issues of the time period in which Abigail Adams and Thomas Jefferson lived. As the lesson proceeded, they took turns eliciting questions, answering questions, and probing students for their thinking about the issues that arose. At a given point in the lesson, one teacher took the lead in answering a question, while the other teacher probed the students to extend their thinking about the answer. As an example, when the teacher portraying Abigail Adams was asked to give her views about women's rights, she answered that she felt women did not belong in Congress. The second teacher asked the students why they thought Abigail Adams answered the question in this way. The students began to discuss women's rights in historical context, shifting back and forth from present to past, while the teachers moved in and out of role to expand and clarify the points being made. Throughout the lesson, they shared the teaching responsibilities. IMPLICATIONS In order to examine how co-teaching approaches and models used by special education teachers and general education teachers could be adapted to the mentor/intern experience, each of the co-teaching models was presented separately. However, the order of presentation is not meant to suggest a linear framework for intern/mentor co-teaching experiences. That is, no one model is put forward as somehow "better" than the others, nor as a paradigm of what to aim for in realizing co-teaching structures. Although complementary teaching is discussed as "easier" to implement early in the intern teaching semester, this model is no less powerful at the end of the semester. Clearly, the instructional strengths of the intern help determine which models to use at a given time. But, more importantly, decisions about the use of a particular model of co-teaching should be based on the content and context in which the model is employed with a given group of learners. As lessons vary in length from a set number of minutes during a given school day to a set of hours spread across several school days, the models become even more interrelated, with pieces of several models appearing during a lesson. EXAMPLE: BLENDED MODEL--SECONDARY CREATIVE MOVEMENT Students have begun exploring the works of significant American choreographers. The mentor and intern designed an instructional sequence that began with an orienting lecture on the social, cultural, and historical backgrounds of selected American choreographers, including how these choreographers worked with other choreographers, their self-described aesthetic, etc. While the lead teacher presented the content, the support teacher helped the students record identifiable elements of each choreographer's work, and map similarities and differences. Following this presentation and recording of content, students worked at stations that the intern and mentor had developed. Each of the stations included text material on a different choreographer (e.g., reviews, biographies, autobiographies, pictures, and videotaped records of performances). At each station, the central task for students was to develop a list of characteristics which would enable them to create and perform a piece of choreography in the style of that choreographer. All students were asked to complete the work at all stations. The mentor and intern then divided the students into two groups--the mentor working with one group, the intern working with the other. Each group was given the same tasks. First, they achieved consensus on which choreographer they would use. Second, they agreed upon the elements of a rubric that enabled the group to create a work in the style of their chosen choreographer. Then, using music that was not heard in the stations, the groups crafted pieces of choreography that they felt met the requirements of the rubric. The groups rehearsed their pieces, assessed their work, and, following any final modifications, presented their works-in-progress to the full class. In their two small groups, students discussed the success of their choreography at capturing and communicating the elements of their choreographer's style. Then, students and teachers shared in a full class review of the sessions, including the orienting lecture, their station work, their parallel explorations, and their shared experiences during the performances. Together, they identified areas for future work. Following the lesson, the mentor and intern discussed their perceptions and reflections of the student's work. They also assessed the efficacy of their work at engaging learners in a creative examination of American choreographers. In this example, the mentor and intern designed, communicated, and monitored teaching and learning episodes that blended complementary, station, parallel, and shared models. While both mentor and intern teachers planned the lesson, their roles changed in defined and spontaneous ways as they implemented various co-teaching models. CONCLUSIONS The field of teacher education continues to need studies and strategies that help provide insights into the collaborative process as it occurs over time between mentors and interns. Having a sense of how co-teachers might collaborate to define, design, and implement discrete structures for instruction can be particularly important in anticipating critical stages of successful intern teaching and successful mentoring. The co-teaching models offer a common language for mentors and interns to use when conceptualizing the collaborative process. Our sense is that if mentors and interns were to be provided with opportunities to learn about models of co-teaching before intern teaching, more dialogue about how to establish their roles and study their roles could take place during the intern teaching semester. However, the field of special education has documented that learning about the models and practicing them is not enough to ensure that co-teaching becomes a part of the school culture. In order to flourish, co-teaching needs an organizational structure that entails a great deal of personal, administrative, and strategic commitment, time, and coordination. As faculty from schools and universities continue to work together to establish more field-based teacher education programs, these organizational issues and related concerns about co-teaching can be addressed. Researchers need to study organizational structures to determine which structures best support co-teaching initiatives. In addition, key aspects that could be examined include: What are the "roles" that develop between the two teachers at various levels of intern teaching? And, how do these roles shift or change as the intern teacher becomes more experienced and the relationship between teacher and intern becomes more collaborative? By using the intern teaching semester as a venue to experiment with current collaborative teaching models developed to link special education teachers and generalist classroom teachers, these questions about the roles of interns and mentors can be addressed directly and purposefully. We believe that the answers to these questions would benefit mentors and interns. But most importantly, we believe the answers would benefit the P-12 students with whom they work. Added material Janet Dynak's professional interests include the study of literacy as it relates to mentoring and field-based teacher education programs. Elizabeth Whitten's professional interests include the study of transdisciplinary collaboration as it relates to special education and general education. David Dynak's professional interests include the study of teacher beliefs and how these impact the formation and evaluation of arts education programs and policies. Figure 1 Cycle of Teaching Practices REFERENCES Bauwens, J., & Hourcade, J. J. (1995). Cooperative teaching: Rebuilding the school house for all students. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Cochran-Smith, M. (1991). Reinventing student teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 42(2), 104-118. Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan. Farris, P. J., Henniger, M., & Bischoff, J. A. (1991). After the wave of reform, the role of early clinical experiences in elementary teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 13(2), 20-24. Feiman-Nemser, S. (1992). Helping novices learn to teach: Lessons from an experienced support teacher (Report No. 91-6). East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, National Center for Research on Teacher Learning. Friend, M., Reising, M., & Cook, L. (1993). Co-teaching: An overview of the past, a glimpse at the present, and considerations for the future. Preventing School Failure, 37(4), 6-11. Gardner, H. (1993). The unschooled mind: How children think and how schools should teach. New York: Basic Books. Holmes Group. (1986). Tomorrow's teachers: A report of the Holmes Group. East Lansing, MI: Author. Lieberman, A. (1995). Practices that support teacher development: Transforming conceptions of professional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 76(8), 591-596. Mentor Teacher Handbook. (1995-1996). Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University, College of Education. Meyers, J., Gelzheiser, L. M., & Yelich, G. (1991). Do pull-in programs foster teacher collaboration. Remedial and Special Education, 12(2), 7-15. Nevin, A., Villa, R., & Thousand, J. (1992). An invitation to invent the extraordinary: Response to Morsink & Lenk. Remedial and Special Education, 13(6), 44-46. Odell, S. J. (1990). Mentor teacher programs. Washington, DC: National Educational Association. Redditt, S. (1991). Two teachers working as one. Equity and Choice, 8(1), 49-56. Villa, R. A., & Thousand, J. S. (1992). How one district integrated special and general education. Educational Leadership, 50(2), 39-41. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Walther-Thoms, C. S., & Carter, K. L. (1993). Cooperative teaching: Helping students with disabilities succeed in mainstream classrooms. Middle School Journal, 25(1), 33-38. York, J. L., & Reynolds, M. C. (1996). Special education and inclusion. In J. Sikula, T. J. Buttery, & E. Guyton (Eds.), Handbook of teacher education (pp. 820-836). New York: Macmillan. WBN: 9710504813007