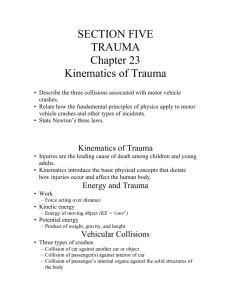

TRAUMA SERIES: POLYTRAUMA Jassin M. Jouria, MD Dr. Jassin

advertisement