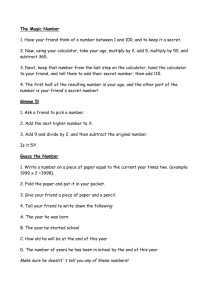

eastawayhandout_0 - The Royal Institution

advertisement

MATHEMATICAL MAGIC TO INVESTIGATE Notes to accompany some of the tricks in the Royal Institution talk. Rob Eastaway www.RobEastaway.com Think of a number The simplest ‘think of a number’ trick is: ‘think of a number…double it…add ten…halve your answer…take away the number you first thought of’. The answer will always be 5. For bright year 5s and older children, this is a fun way of introducing the idea of algebra. If you call the number you think of ‘X’ (or something friendly like ‘Blob’) then you can show how any value of X leads to the result 5. Think of a number…”Blob”…Double it…”Blob Blob”…add 10…”Blob Blob + 10”…divide by 2…”Blob + 5”…and take away the number you first thought of…leaving “5”. There are many more complicated examples, such as: (a) How many biscuits did you have yesterday? (pick a number between 1 and 10) (b) Multiply this number by two. (c) Add 5. (d) Multiply the answer by 50. (e) If you have already had your birthday this year, add 1764, otherwise add 1763. (f) Now subtract the four digit year that you were born. The first digit is the number of biscuits, the last two digits are your age. [If the year is 2015, add 1765/1764 for 2016 add 1766/1765 and so on.] Get the class to create their own fool-proof think-of-a-number tricks. Repeating digits Pick a number between 1 and 9 (call it N). Multiply it (in any order) by 3, 7, 11, 13, 37. The answer will always be NNNNNN. This is because 3 7 11 13 37 are the factors of 111,111. This helps to reinforce the principle that the order of multiplication doesn’t make any difference. You can also use it to investigate factors of other interesting numbers. What numbers, if any, can be divided exactly into 111, 1111, 11111…? Another factor trick is to think of a three digit number (ABC) and write it twice on a calculator (ABCABC). If you now divide this by lucky numbers 7, 11 and even ‘unlucky 13’, the answer will be ABC. (7 x 11 x 13 = 1001, which is the secret behind the trick.) Mind-reading cards Prepare four cards as follows: 8 12 9 13 10 14 11 15 4 12 5 13 6 14 7 15 2 10 3 11 6 14 7 15 1 9 3 11 5 13 7 15 Think of a number between 1 and 15. If your number is on the card, add the top left hand corner number on the card to your mental total. After all four cards, your mental total will be the number that was thought of. This trick is a great introduction to the vital (but non-curriculum) topic of binary arithmetic, the basis of all computer logic. All numbers can be expressed as a combination of the powers of 2, i.e. 1, 2, 4, 8, 16… For example 10 = 8+2, 15=8+4+2+1 . ‘Yes’ in the trick is equivalent to the number 1 in binary, and ‘no’ is equivalent to 0. So the number 13 is 8-Yes 4-Yes 2-No 1-Yes, or “Yes Yes No Yes”, which in binary is 1 1 0 1. Using the Yes/No principle, get the class to create the binary codes for numbers up to 32. The Bart Simpson trick Shuffle a pack of 5 cards, and make sure that Bart (or whatever your chosen card is) is bottom of the pack. Ask somebody to give you a number between 2 and 4 (‘N’). Now count the cards from the top of the pack to the bottom, turning over the Nth card to show it isn’t Bart, and placing it face-up on the bottom. Keep doing this until there is one card face down. That card will be Bart. The explanation of this trick is actually quite subtle, to do with prime numbers and common factors. Number the cards 1 to 5, with Bart as 5, and suppose the audience member chooses 3. The circled cards are turned over: 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 Card numbers 3, 1, 4 and 2 are all turned over before 5. Why? Because a multiple of 3 will only coincide with a multiple of 5 when 15 cards have been turned over. This will work for any number of cards K so long as K is a prime number. If K is not prime, the trick MAY still work, but may also go wrong. For example, if K is 6 and the audience member chooses, say, 3, the trick won’t work – Bart will appear second, because 2x3=6. You can get the children to investigate whether the trick always works for 4 or 8 cards. Magic square 7 3 4 6 5 1 2 4 4 0 1 3 6 2 3 5 Circle any number in the square. Then cross out the other numbers in its row or column. Circle another number and repeat the crossing out for the row and column. Do the same for two more numbers. The four numbers you have chosen, seemingly at random, will add to 14. To prepare a magic square like this, first decide what ‘magic’ number you would like. Suppose it is 20. You can now choose a square grid of any size. Around the edges of the squares, put numbers that add up to 20. For example: 4 3 1 2 7 3 Fill in the squares in the table by adding the number above the column to the number by the row (so the top left here is 2+4=6). The trick now works. Get the class to create their own magic squares, eg for birthday cards. One way to see how it works is to replace the numbers with names, eg Anne, Betty, Clare, Dave, Ed, Fred. Whichever three squares you choose, you will always end up with one name from each row and column. Magic colour G F H E I D J 1. Think of a number bigger than three 2. Count the number, 1 is A, 2 is B etc 3. Count back around the circle by the same number. 4. You will always end on the colour at position “I”. Investigate why it works, and what happens if you make a bigger circle or longer tail. K C B A Start Here There are more mathematical games and investigations appropriate for primary children in “Maths for Mums & Dads” and “How Many Socks Make a Pair?” www.RobEastaway.com