Neuroscience Report - University College London

advertisement

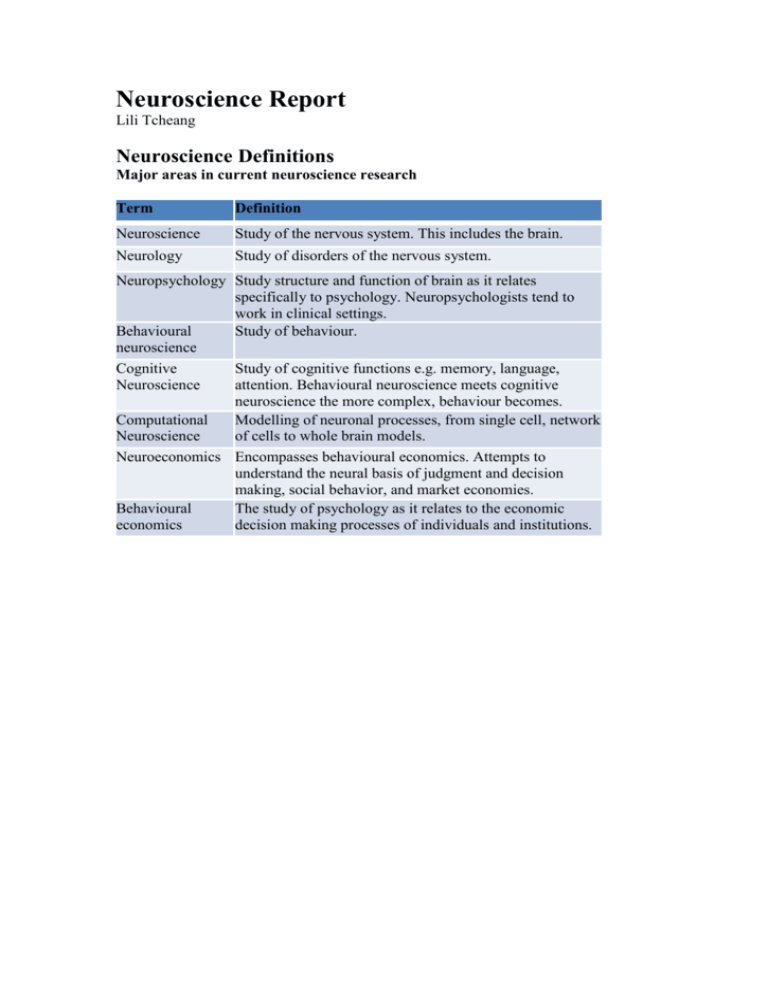

Neuroscience Report Lili Tcheang Neuroscience Definitions Major areas in current neuroscience research Term Definition Neuroscience Study of the nervous system. This includes the brain. Neurology Study of disorders of the nervous system. Neuropsychology Study structure and function of brain as it relates specifically to psychology. Neuropsychologists tend to work in clinical settings. Behavioural Study of behaviour. neuroscience Cognitive Study of cognitive functions e.g. memory, language, Neuroscience attention. Behavioural neuroscience meets cognitive neuroscience the more complex, behaviour becomes. Computational Modelling of neuronal processes, from single cell, network Neuroscience of cells to whole brain models. Neuroeconomics Encompasses behavioural economics. Attempts to understand the neural basis of judgment and decision making, social behavior, and market economies. Behavioural The study of psychology as it relates to the economic economics decision making processes of individuals and institutions. A brief history of Neuroscience Neuron Structure Camillo Golgi used silver chromate to stain and reveal neuronal structure. EEG electroencephalography Hans Berger publishes findings about the first human electroencephalogram Drug Dexedrine (an amphetamine) introduced to treat narcolepsy Technological developments 1861 1873 1874 1888 1890 1906 1909 1911 1929 1935 1936 Lobotomy Neuron Doctrine The basic functional unit of the brain is the neuron by Santiago Ramon y Cajal. Theoretical developments Egas Moniz publishes work on the first human frontal lobotomy. Functional Localisation Brodmann describes 52 discrete cortical areas – still used today to identify and allocate function Wernicke’s Area Carl Wernicke discovered Wernicke’s area (left posterior, superior temporal gyrus) where damage to this area led to the loss of language comprehension, although speech was produced normally. Broca’s Area Paul Broca suggests certain brain regions responsible for certain function. Discovered broca’s area of the brain (left inferior frontal gyrus), where damage to this area led to the inability to produce speech. Brain Firing Schizophrenia Roy & Sherrington link blood flow to brain region with neuronal firing Schizophrenia first coined by Eugen Bleuler Alzheimers Alois Alzheimer describes presenile dementia TMS Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation A brief history of Neuroscience PET/MRI Positron Emission Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging Technological developments M.E.Phelps, E.J.Hoffman and M.M.Ter Pogossian develop first PET scanner First MRI image (a mouse) is taken by Paul Lauterbur, Peter Mansfield (University of Nottingham) refined his technique so that images would take seconds as opposed to hours to collect DRUG Parkinsons Levadopa successfully treats parkinsonism First successful Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation study by Anthony Barker and colleagues. DBS Deep Brain Stimulation Parkinsons First Deep Brain stimulation performed on Parkinson patient. MEG First MEG signals measured 1953 1960 1961 1952 Cell electrical properties Modern understanding of the electrical properties of nerve cells from work of Hodgkin and Huxley on the squid giant axon. Theoretical developments Parkinson’s Oleh Hornykiewicz shows that brain dopamine is lower than normal in Parkinson's disease patients Hippocampus Brenda Milner discusses patient HM who suffers from memory loss of hippocampal surgery 1968 1974 1985 1987 1990 fMRI Born functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Seiji Ogawa discovers differences in MRI images between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. In neuroimaging the blood oxidation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast is considered a marker for neuronal activity at localised sites of the brain. Basic Neuroanatomy The following diagram and descriptions relate to key areas of interest in the brain. Neocortex incorporates the most evolutionarily developed areas of the brain. A measure of human intelligence is often argued on the basis of the larger relative size of neocortex to the rest of the brain in humans compared with other animals. The limbic system is a group of interconnected structures that mediate emotions, learning and memory. Neocortex Neocortex Occipital lobe – helps process visual information. Parietal lobe – receives and processes information about temperature, taste, touch, and movement coming from the rest of the body. Reading and arithmetic are also processed in this region. Temporal lobe – processes hearing, memory and language functions. Frontal lobe – helps control skilled muscle movements, mood, planning for the future, setting goals and judging priorities. Limbic System Amygdala – limbic structure involved in many brain functions, including emotion, learning and memory. It is part of a system that processes "reflexive" emotions like fear and anxiety. Cerebellum – governs movement. Hippocampus – plays a significant role in the formation of long-term memories. Neuroscience Tools This section is divided into two sections. Passive techniques involve those that measure brain activity and do not affect brain function. Active techniques are tools that influence neuronal activity in the brain. Neuroscience theories use evidence from a compliment of techniques drawing on a number of corroborating experiments to back their conclusions. Passive Techniques Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Brief Description Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Applications Pros Cons Resolution Anatomical structure A powerful magnetic Spatial resolution: Used to identify stroke damage. Allows identification of Participants must not have of the brain field aligns the 0.5 - 1mm3 Has been used to identify platelet specific brain structures, metal implants, pacemakers or visualised. magnetization of (several hundred levels in potential alzheimer’s whose size can be other such medical devises. Can be shown for some atomic nuclei in thousand neurons) patients although now, this is thought correlated with Participants must not be individual brains the human body Temporal not to correlate with alzheimer’s behaviour or claustrophobic. Radio frequency resolution: diagnosis. performance. Requires participants to lie fields systematically ~ seconds On group level, used to correlate size supine and still for long alter the alignment of of brain areas to specific behaviours periods in a noisy and enclosed this magnetization. or characteristics. i.e. alzheimers environment. Causes the nuclei to patients tend to have smaller Experimental conditions limit produce a rotating hippocampi the type of experiment that can magnetic field Used experimentally to show brain be performed. detectable by the plasticity over a lifetime. E.g. taxi scanner drivers’ hippocampal size correlates with their years of experience in navigating, as opposed to bus drivers who follow a specific route, where no correlation was found. Passive Techniques Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) Brief Description Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Resolution Measures localised brain activity as opposed to structure in MRI. Although individual brain activity can be extracted, effects are often summated over a group of brain scans. Used in conjunction with eeg or meg in order to extract good time resolution. Eeg can be used simultaneously with fMRI. Relies on the assumption 2cm that localised neuronal ~secs activity directly affects brain oxygenation levels. Therefore affecting blood flow directly to brain region. Blood flow can be detected through brain imaging. Applications Pros Cons Clinicians use it to map functional brain areas in order to assess potential damage before surgery. Used extensively in research to identify areas of function with behaviour and performance. Links performance directly to activation of specific brain region. In research, often only conclusive within groups of subjects. Similar to MRI. Signals critical for perception, thought or actions that are encoded at a finer spatial scale may be hard to detect. Passive Techniques Electroencephalography (EEG) Brief Description Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Resolution Measures brain activity, Electrical activity Msec resolution (2kHz) through residual generated by neuronal electrical signals detected firing produces a at the scalp spatially distributed Characteristic wave residual signal at the patterns used to identify scalp that is recorded by sleep states in numerous electrodes participants. attached at regular intervals to the scalp. Applications Pros Cons US military developing High temporal Significantly low spatial mind reading through eeg Resolution resolution to enable soldiers to Relatively cheap Poor resolution of brain communicate movements Relatively portable activity below surface in battlefield. Relatively tolerant to level neurons. Many commercial games subject movement Unlike PET cannot have been developed Silent (useful for identify specific locations such as balancing a ball auditory stimuli) at which with the mind. Does not aggravate neurotransmitters, drugs Many applications in claustrophobia can be found1. development for Detects covert processing Set-up and precise paralysis patients, (i.e. participant does not electrode locating, timelocked-in syndrome need to physically consuming. patients and so on, to use respond) Signal to noise ratio brain activity to control poor. external manipulators as a way to interact with the world. Passive Techniques Magnetoencephalography (MEG) Brief Description Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Resolution Applications Participants sit in upright position, with their heads in a stationary position in the scanner. Neuronal activity induces 1 msec precision Clinical: detection and a weak associated Spatial Resolution: localisation of epilepsy. magnetic field, that is Accurately pinpoints detected by MEG. primary auditory cortex, somatosensory areas and motor areas. Pros Cons High temporal resolution Magnetic fields less distorted by skull and scalp compared with eeg signal. Only detects tangential components. Therefore only detects activity in brain sulci (brain creases at 90 deg to brain surface). However any activity detected is more accurately located. Must be highly shielded due to weakness of signal. Requires testing room to be enclosed in metal housing. Active Techniques Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Brief Description Mechanism First demonstrated in Magnetic 1985 induction: A Pulsed signal can be moving electrical single, double or field, caused by a repetitive, creating current flow in a inhibition (virtual lesion) wire, induces a or excitation of the cortex moving magnetic as desired. field, which in Essentially causes turn induces a temporary virtual lesion moving electrical in the brain with current in Used to assess the role of neurons in the brain area on specific brain. behaviours. Cleared in 2008 for use in depression by FDA2. Spatial/Temporal Applications Resolution Pros Cons Tens of msec Diagnoses connections between primary No long term Can only target cortical areas resolution. motor cortex and muscle to evaluate effects close to the surface of the Spatial resolution, damage from strokes, spinal cord Virtual lesion brain. function of coil injuries, multiple sclerosis and motor enables Difficulties in targeting frontal 456 shape, size and neuron disease . investigation of role cortical areas due to applied magnetic Repetitive TMS alleviates7 of specific brain uncomfortable side effects in field. Typically Schizophrenia region to cognitive facial muscles in the vicinity. 7mm – tens of cms. However still controversial as one large- function. Very small risk of seizure Focal enough to scale study refutes this8. High temporal associated with medication or stimulate individual Metaanalyses suggest certain types of resolution enables recent changes in biological finger regions3 major depression alleviated using studying the clock. 9 rTMS temporal dynamics Seizures not associated with Can temporarily reduce chronic pain of certain previous history of epilepsy, and change pain-related brain and nerve processes. nevertheless participants with a activity, as well as predict the success of family history of epilepsy are surgically implanted electrical brain ruled out. stimulation for the treatment of pain10. Active Techniques Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (TES) Brief Description Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Applications Resolution Around since 19th century although superceded by electroshock therapy and ignored until very recently11. Application of low-intensity Relatively diffuse current to scalp. throughout brain This can be as a direct current (transcranial direct current stimulation – TDCS) or as an alternating current (transcranial alternating current stimulation – TACS). TDCS, modulates neuronal excitability depending on the direction of the applied current (Anodal stimulation increases excitability, cathodal decreases it). TACS entrains frequency specific neural oscillations in the brain. TDCS therapeutic effects shown in clinical trials involving Parkinson’s disease12, tinnitus, fibromyalgia, and post-stroke motor deficits13. TACS has currently been used in an experimental context to induce phosphenes in the visual areas of the brain. Pros Cons Less expensive, more Less spatial and portable temporal resolution Easier to control compaired with TMS. modulation direction by switching voltage direction Insensitive to subject head movements, therefore allowing stimulation during sleep. Less associated risks although experimental screening procedures identical to TMS due to novelty of technique. Active Techniques Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) Brief Description 1 Mechanism Spatial/Temporal Applications Pros Cons Yasuno et al (2008). "The PET Radioligand [11C]MePPEP Binds Reversibly and with High Specific Signal to Cannabinoid CB1 Receptors in Nonhuman Primate Brain." Resolution Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 259-269. 2 http://www.rush.edu/rumc/page-1266946139826.html Surgically implanted powered neurostimulator n/a Used to treat Can reach deeper areas Associated surgical risks. 3 Ro T, Cheifet S, Ingle H, Shoup R, Rafal R(1999) Localization of the human frontal eye fields and motor hand 14 area with transcranial magnetic stimulationCalibration and magneticof electrodes ‘brain pacemaker’ for sends electrical activity Parkinson’s , chronic of the brain. resonance imaging. Neuropsychologia 37:225–231 disorders to to target site. relief in veryNeurology 68 (7): 484–488. specific to each patient 4 Rossini, P;resistant Rossi, S (2007). "Transcranial magnetic stimulation: diagnostic, therapeutic, andpain research potential". 15 5other forms of treatment. Underlying principles specific cases . and time-consuming. Dimyan, MA; Cohen, L (2010). "Contribution of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the understanding of mechanisms of functional recovery after stroke". Neurorehabilitation FDA approved inand 1997 Neuraland Repair mechanisms 24 (2): 125–135. are still Used experimentally to Displacement of 6 16 Nowak, D; Bösl, K; Podubeckà, J; Carey, J (2010). "Noninvasive brain stimulation and motor recovery after stroke". Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience 28 (4): 531– not clear. treat major depression electrodes during surgery 544. 17 and tourettes syndrome can lead to serious 7 Aleman,A. et al. (2007) Efficacy of low repetitive transcranialmagnetic stimulation in the treatment of resistant auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. J. although results are as complications and side Clin. Psychiatry 68, 416–421 41 yet inconclusive. effects. 8 Slotema, C.W. et al. (2011) Can low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation really relieve medication-resistant auditory verbal hallucinations? Negative results from a large randomized controlled trial. Biol. Psychiatry 69, 450–456 9 Slotema, CW; Blom, JD; Hoek, HW; Sommer, IEC (2010). "Should We Expand the Toolbox of Psychiatric Treatment Methods to Include Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 71 (7): 873–884. 10 Rosen, AC; Ramkumar, M; Nguyen, T; Hoeft, F (2009). "Noninvasive Transcranial Brain Stimulation and Pain". Current Pain and Headache Reports 13 (1): 12–17. 11 Utz, K. S., Dimova, V., Oppenlander, K., & Kerkhoff, G. (2010). Electrified minds: Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and Galvanic Vestibular Stimulation (GVS) as methods of non-invasive brain stimulation in neuropsychology-A review of current data and future implications. Neuropsychologia, 48(10), 2789–2810. 12 Boggio et al. (2006). Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory in patients with Parkinson's disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 249:31–38. 13 Norris, S., Degabriele, R., Lagopoulos, J. (2010.) Recommendations for the use of tDCS in clinical research. Acta Neuropsychiatrica 22: 197–198. 14 Kringelbach ML, Jenkinson N, Owen SLF, Aziz TZ (2007). "Translational principles of deep brain stimulation". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 8:623–635. 15 Young RF & Brechner T. Electrical stimulation of the brain for relief of intractable pain due to cancer. Cancer. 1986;57:1266–72. 16 Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009 May;22(3):306–11 Mink JW, Walkup J, Frey KA, et al. (November 2006). "Patient selection and assessment recommendations for deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome". Mov Disord. 21(11):1831–8. 17 Neuroscience Diseases This section contains three main subsections comprising of neuroscience diseases that will have greatest impact for the nation. These are Neurodegenerative diseases, neurodevelopmental diseases and neurological diseases. Neurodegenerative Disease Dementia Description Cause Main causes3: Vascular dementia gradual hardening and narrowing of blood vessels, interrupting blood flow to brain. Early onset dementia Risk factors: diabetes, occurs to under 65 obesity, smoking, year olds and excessive drinking, accounts for 2% of lack of exercise, high cases. fat diet. Dementia with Lewy The second leading bodies – small circular health concern after proteins that develop cancer in US1,2 in brain. Origin unknown. Fronto-temporal dementia – frontal half of the brain becoming damaged and shrinking. A non-specific illness with a number of symptoms - serious loss of general cognitive ability. Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Cost increasing difficulties with tasks and activities that require concentration and planning •memory loss •depression •changes in personality and mood •periods of mental confusion •low attention span •urinary incontinence •stroke-like symptoms, such as muscle weakness or paralysis on one side of the body •visual hallucinations (seeing things that are not there) •wandering during the night •slow and unsteady gait (the way that you walk) Non-specific and based on cooccurrence of a number of symptoms. Symptoms must be persistent over 6 months. Cognitive testing e.g. abbreviated mental test score (AMTS), mini mental state examination (MMSE). Routine blood tests used to rule out treatable causes e.g. vitamin abnormalities. Neuroimaging to look for atrophy of brain, stroke but cannot confirm cases alone. No clinical cure. Current drugs treat behavioural and cognitive symptoms not underlying pathophysiology. ¼ of NHS hospital beds at any one time4 2012 updated figures from Dementia UK5, £23 billion annually, 800K cases. Cost include formal care +financial value of informal care (1/3 of all care) Alzheimers Description Cause Symptoms A degenerative brain Amyloid Plaques Can be diagnosed without any external disease resulting in • Accumulation of amyloid symptoms7 progressive mental plaques between nerve cells weakening with (neurons) in the brain. External symptoms include8: disorientation, memory • Amyloid: a general term for Routinely place important items in odd disturbance and protein fragments that the places: keys in fridge, wallet in disorder. body produces normally. dishwasher Not to be confused • In a healthy brain, these Forget names of family members & with dementia, defined protein fragments are broken common objects as a “progressive brain down and eliminated. Frequently forget entire conversations dysfunction that Neurofibrillary Tangles Dress regardless of the weather, wear eventually leads to the • Neurofibrillary tangles: several skirts on warm day, or shorts in limitation of daily insoluble twisted fibers found snow storm activities.” inside the brain's cells. Can’t follow recipe directions Alzheimers can lead to • Consist primarily of a protein Can no longer manage checkbook, some forms of called tau, which forms part of balance figures, solve problems, or think dementia6 a structure called a abstractly. microtubule, which helps Withdraw from usual interests and transport nutrients and other activities, sit in front of the TV for hours, important substances from sleep far more than usual one part of the nerve cell to Get lost in familiar places, don’t another. remember how you got there or how to • In Alzheimer's disease, get home however, the tau protein is Experience rapid mood swings, from abnormal and the microtubule tears to rage, for no discernible reason structures collapse. Diagnosis Often difficult − particularly at early stages. Definite diagnosis may only be confirmed after death. MRI currently being developed as a biomarker for early diagnosis9 Treatment No known cure. Drug treatment can alleviate symptoms. Alternative therapies have often been tried, although no scientific evidence to back claims1011. Cost Parkinsons Description Cause Symptoms A person with PD has two to six times the risk of suffering dementia compared to the general population12. Unknown true cause, however Tremor, rigidity, Parkinson’s slowness of patients have a movement. depletion of dopamine (a neurotransmitter) in the substantia nigra region of the brain. Often associated with catastrophic failure The substantia nigra plays an important role in reward, addiction, and movement.13 Diagnosis Treatment Cost Currently no lab test clearly identifies the disease Brain scans are sometimes used to rule out disorders that could give rise to similar symptoms Drugs: Levodopa converts to dopamine in the brain MAO-B inhibitors (selegiline and rasagiline) increase the level of dopamine in the basal ganglia by blocking its metabolism14 Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation temporarily improves levodopa-induced dyskinesias15. Its usefulness in PD is an open research topic16, although recent studies have shown no effect by rTMS17. Deep Brain Stimulation as a last resort treatment. Lesions in specific subcortical areas (a technique known as pallidotomy in the case of the lesion being produced in the globus pallidus)18. Most treatments researched using MPTP monkey models. MPTP is a neurotoxin that destroys dopaminergic neurons, inducing Parkinson’s disease. 2007 Annual cost in the UK is estimated to be between 449 million and 3.3 billion pounds19. Broken down by: NHS direct costs, Social Service costs, Private related expenditure as well as lost productivity lost leisure time and carer replacement cost. Figures represent an extreme of accounting for the last 3 points and a conservative (58,600) to higher prevalence (100,000) of the disease. Developmental Disorders ADHD Description Cause Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Developmental disorder, involves lack of impulse control and inattention. Brain imaging of prefrontal cortex shows lag of 3-5 years. Co-occurs with sleep disorders. 1.7% of population affected mostly children and males. Exact cause unknown. Twin studies suggest genetic cause, although mechanism is complex Easily distracted, miss details, forget things, and frequently switch activity. Have difficulty maintaining focus Become quickly bored Clinical diagnosis through Combination of interview. medication and therapy In Children: most effective, followed • symptoms continuous 6 by medication, then months therapy. • symptoms before age 7 Also recommended in children to address Adult diagnosis more associated sleep difficult due to developed problems before other coping mechanisms that therapies considered. mask symptoms. Autism Description Cause Symptoms Diagnosis Restricted social No. of genetic Restricted social Parents may notice interaction and variants interaction, signs by age 2. communication skills. Evidence communication. Based on behaviour Difference in brain inconclusive. Repetitive behaviour. ratings based on organisation Controversial study parent interview and processing of showed links to clinical observations incoming inputs. vaccines and interactions with Asperger’s milder No subsequent the child. form, individuals scientific study has function been able to replicate independently. this finding. Prevalence .2% of Subsequently been population. Sex retracted by the ratios M:F 4:1. Lancet (medical journal) although media coverage periodically surfaces regarding it. Treatment Cost No single universal treatment. Intensive, sustained special education and behaviour therapy early in life improves chances for selfcare, social and job skills52. Critical periods for intervention unsubstantiated. £27billion annually. £2.7 billion towards children, £25 billion on adults. Costs include services: health, social care, special education, Housing (outside parental home), leisure services, outof-pocket payments made for services and lost employment costs. Dyslexia Description Cause Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Difficulty in comprehension accuracy in reading, not correlated with IQ. Prevalence 4-8% of school children with boys 1.5 – 3 times more likely to suffer. Partially genetic Caused by abnormalities in the brain areas responsible for speech and writing. Delays in speech, letter reversal or mirror Verbal and writing, and being easily distracted by spelling tests. background noise. Not funded Difficulty identifying/generating rhyming on the NHS. words, counting syllables in words, segmenting words into individual sounds, or blending sounds to make words, with word retrieval or naming problems. Commonly very poor spelling Educational aids can manage disorder. 95% of children respond well to educational interventions. Description Cause Symptoms Treatment Akin to dyslexia, not linked to IQ. Current potential causes: Neurological: lesions to supramarginal and angular gyri1. Hereditary disorder? Evidence not yet concrete. Deficit in subitizing - the ability to know, from a brief glance and without counting, how many objects there are in a small group Difficulty with everyday tasks like reading analog clocks Inability to comprehend financial planning or budgeting. Difficulty with conceptualizing time and judging the passing of time. Problems with differentiating between left and right Difficulty reading musical notation Difficulty navigating or mental rotation. Dyscalculia 1 Diagnosis Software intended to remediate dyscalculia has been developed. Levy LM, Reis IL, Grafman J (August 1999). "Metabolic abnormalities detected by 1H-MRS in dyscalculia and dysgraphia". Neurology 53 (3): 639–41. Neurological Schizophrenia Description Cause Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Cost Mental disorder characterized by a breakdown of thought processes and by poor emotional responsiveness20 Normal onset is young adulthood Not a split personality disorder as commonly misperceived21. fMRI and PET studies show brain activity differences in frontal lobes, hippocampus, and temporal lobes22 Combination of genetics and environment23 Heritability vary due to the number of genetic factors implicated24. >40% identical twins share symptoms21 Urban environments increase risk x2 21,25 Social isolation, migration and other social factors26 Associated with substance misuse, such as cannabis, cocaine and amphetamines21. More incidences in winter or spring births in the northern hemisphere or other stresses during fetal development27. Auditory hallucinations. Paranoid/bizarre delusions. Disorganized speech and thinking. Significant social or occupational dysfunction 3 diagnostic criteria must be met28: >2 of the following, mostly present in 1 month: Delusions, Hallucinations, Disorganized speech, Grossly disorganized behavior, Negative symptoms: Blunted affect, alogia or avolition Social or occupational dysfunction Significant duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance for at least 6 months. Antipsychotic medication In the UK, in can reduce the "positive" economic terms: symptoms of some 80 million 29 psychosis . working days are lost Psychotherapy: widely each year at a cost recommended, not of £3.7 billion; the widely used, due to NHS spends around reimbursement problems £1 billion on or lack of training30. treatment and Cognitive behavioral personal social therapy (CBT) used to services another target specific £400 million34. symptoms31. Cognitive remediation therapy, a technique aimed at remediating the neurocognitive deficits sometimes present in schizophrenia32. Family Therapy, addresses whole family system of an individual 33. Depression Description Cause More common in Inconclusive. 35 women than men , Proposed urban populations36 causes: psychological, psycho-social, hereditary, evolutionary and biological factors as well as long term drug use Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment Affects family and personal relationships, work or school life, sleeping and eating habits, and general health. No definitive test. Psychotherapy delivered to 2011 Doctors individual, group or family by £8.6billion41 examination will mental health professionals. rule out medical Cognitive Behavioural Therapy – conditions with talking therapy designed to similar symptoms question automatic e.g. thyroid negative/destructive thoughts. disorders. National Institute for Health and Specialist therapist Clinical Excellence (NICE) discusses history of recommend it for clinical symptoms. depression37 Medication: Only effective in severe depression38. Side effects mediated through dosage39 Electroconvulsive therapy – pulse of electricity through brain induces a seizure in patient under general anaesthesia. Recommended as quick therapy for catatonic or severely suicidal patients40 Cost Anxiety Description Cause State of Biological: chemical apprehension, balances in the brain uncertainty and fear. (linked to genetics) Psychological: life Adolescent study experience triggers. showed higher activity in nucleus acumbens when as infants, observed to be highly apprehensive, vigilant and fearful42. Neural circuitry of amygdale and hippocampus also implicated43. Co-occurs with depression. 1 Symptoms Diagnosis •restlessness Symptoms present •a sense of dread for more than 6 •feeling constantly months. 'on edge' •difficulty concentrating •irritability •impatience •being easily distracted •dizziness •drowsiness and tiredness •pins and needles •palpitations •muscle aches and tension •dry mouth •excessive sweating •shortness of breath •stomach ache •nausea •diarrhoea •headache •excessive thirst •frequent urinating •insomnia44 Swaminathan, N. (2012 February). How to Save Your Brain. Psychology Today. Volume45. 74-79 Treatment Therapy: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy focuses on addressing thoughts. Exposure Therapy: confront source of anxiety in controlled environment. Medication: is most effective when used in conjunction with therapy45. Cost 2 http://www.alzheimer-europe.org/Research/Value-of-knowing http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Dementia/Pages/Causes.aspx 4 http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=788 5 http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=418 6 http://diseasealzheimers.com/difference.php 7 Roan S (August 9, 2010). "Tapping into an accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/health/boostershots/aging/la-heb-alzheimers20100809,0,5683387.story 8 http://www.helpguide.org/elder/alzheimers_disease_symptoms_stages.htm 9 http://www.alzforum.org/new/detail.asp?id=3016 10 http://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=134 11 Simon Singh, Edzard Ernst (2008).Trick Or Treatment: The Undeniable Facts About Alternative Medicine, W. W. Norton & Company. 12 Caballol N, Martí MJ, Tolosa E (September 2007). "Cognitive dysfunction and dementia in Parkinson disease". Mov. Disord. 22 (Suppl 17): S358–66. doi:10.1002/mds.21677. PMID 18175397. 13 Jankovic J (April 2008). "Parkinson's disease: clinical features and diagnosis". J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatr. 79 (4): 368–76. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. PMID 18344392. http://jnnp.bmj.com/content/79/4/368.full. 14 The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Symptomatic pharmacological therapy in Parkinson’s disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 59–100. 15 Koch G (2010). "rTMS effects on levodopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease patients: searching for effective cortical targets". Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28 (4): 561–8. 16 Platz T, Rothwell JC (2010). "Brain stimulation and brain repair—rTMS: from animal experiment to clinical trials—what do we know?". Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28 (4): 387–98. 17 Arias P, Vivas J, Grieve KL, Cudeiro J (September 2010). "Controlled trial on the effect of 10 days low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on motor signs in Parkinson's disease". Mov. Disord. 25 (12): 1830–8. 18 The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions, ed. (2006). "Surgery for Parkinson’s disease". Parkinson's Disease. London: Royal College of Physicians. pp. 101–11. 19 Findley LJ (September 2007). "The economic impact of Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 13 (Suppl): S8–S12. 20 Schizophrenia" Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2010 21 Picchioni MM, Murray RM. Schizophrenia. BMJ. 2007;335(7610):91–5. 22 Kircher, Tilo and Renate Thienel. The Boundaries of Consciousness. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. ISBN 0444528768. Functional brain imaging of symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia. p. 302. 23 van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):635–45 24 O'Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ. Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia. Hum. Mol. Genet.. 2003;12 Spec No 2:R125–33. 25 Becker T, Kilian R. Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement. 2006;429(429):9–16. 26 Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E, Kahn RS. Migration and schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20(2):111–115. 27 Yolken R.. Viruses and schizophrenia: a focus on herpes simplex virus.. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 2):83A–88A 28 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2000 29 The Royal College of Psychiatrists & The British Psychological Society (2003). Schizophrenia. Full national clinical guideline on core interventions in primary and secondary care (PDF). London: Gaskell and the British Psychological Society. Retrieved on 2007-05-17. 30 Moran M (18 November 2005). "Psychosocial Treatment Often Missing From Schizophrenia Regimens". Psychiatr News 40 (22): 24. http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/40/22/24-b. Retrieved 2007-05-17. 31 Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N (May 2008). "Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor". Schizophr Bull 34 (3): 523–37. 3 32 Wykes T, Brammer M, Mellers J et al. (2002). "Effects on the brain of a psychological treatment: cognitive remediation therapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging in schizophrenia". British Journal of Psychiatry 181: 144–52 33 Glynn SM, Cohen AN, Niv N (January 2007). "New challenges in family interventions for schizophrenia". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 7 (1): 33–43. 34 http://schizophrenia.com/szfacts.htm 35 Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. 36 37 Gelder, M., Mayou, R. and Geddes, J. 2005. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford. pp105 http://mbct.co.uk/about-mbct/ Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. (January 2010). "Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis". JAMA 303 (1): 47–53. 39 Karasu TB, Gelenberg A, Merriam A, Wang P. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder (Second Edition). Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4 Suppl):1– 45 40 American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000b;157(Supp 4):1–45. 41 http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/depression-costs-economy-16386bn-a-year-1706018.html 42 Bar-Haim Y, Fox NA, Benson B, Guyer AE, Williams A, Nelson EE, Perez-Edgar K, Pine DS, Ernst M. (2009). Neural correlates of reward processing in adolescents with a history of inhibited temperament. Psychol Sci. 20(8):1009-18. 43 Rosen JB, Schulkin J (1998). "From normal fear to pathological anxiety". Psychol Rev 105 (2): 325–50. 44 http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Anxiety/Pages/Symptoms.aspx 45 http://www.helpguide.org/mental/anxiety_types_symptoms_treatment.htm 38 Neuroscience and the Media This section provides clarity to some of the neuroscience myths being perpetuated in the media and limits to its application. • We do not use only 10% of our brain – Brain activity is constant; it’s going on all the time. In reality a lot of research in neuroimaging has examined the ‘resting’ brain state, since there are a set of brain regions consistently more active during this than during a task. 2 Figure 1: Certain sleep stages show greater amplitude brain oscillations compared with being awake. Furthermore, Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep stage, the period in which we dream, shows much smaller amplitude oscillations, although this is the stage that many of us remember as quite active when awake. 2 Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, Buckner RL, Miezin FM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE (1997) Common blood flow changes across visual tasks. II. Decreases in cerebral cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 9:648–663. Brain Imaging in the Media Appeals: Appears to mirror reductionist approach that is standard in science, e.g. chemistry can be reduced to atomic particles, behaviour reduced to a brain region. Problems and pitfalls: fMRI images betray complexity of processing that goes into producing an image as well as the complexity of brain processes that underlie the image data. Brain regions alone cannot explain complicated behaviours/emotions that accompany them. fMRI images are not photographs, unlike X-rays. fMRI images undergo huge amounts of post-processing, from smoothing data, fitting to a template brain, and large-scale statistical processing, to arrive at the final image. Typically individual brains vary substantially in shape and size, a fact which is lost in the final brain image. fMRI does not measure activity per se, but contrasts in activity. Therefore a brain image cannot interpret a behaviour in isolation, but is always a contrast between one behaviour and another. Failure to appreciate this can lead to misunderstadings. E.g. One news headline: “The scientists found that female voices activate the brain's auditory section, but male voices activated the area at the back of the brain called the mind's eye”3. Because in the experiment, listening to male voices had to be compared to listening to female voices, the subsequent analysis uses the male voice as the baseline measure. This did not mean that male voices did not activate auditory cortex at all. Real time fMRI – Pitfalls – assumes a linear correlation between brain area and activation and behaviour. Individual brains do not necessarily reflect population behaviour. – Uses in research limited due to analysis intensive technique and noise. Used interactively to mediate pain perception in participants, who focus on reducing activation in known brain area. fMRI and the Law • noliemri.com claims to detect lying unequivocally using fMRI. – Oversimplification of neural correlates of lying. Viegas J.(2005, August 2). It’s official! Listening to women pays off. ABC Science. Retrieved October 12, 2009, from http://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2005/08/02/1428081.htm 3 – Website cites only 5 publications (latest 2005) – Subsequent publication in same journal: “fMRI-based deception detection measures can be vulnerable to countermeasures, calling for caution before applying these methods to real-world situations”4 4 Giorgio Ganis, J. Peter Rosenfeld, John Meixner, Rogier A. Kievit, Haline E. Schendan, Lying in the scanner: Covert countermeasures disrupt deception detection by functional magnetic resonance imaging, NeuroImage, Volume 55, Issue 1, 1 March 2011, Pages 312-319, ISSN 1053-8119, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.025. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811910014552) Policy Education: Usha Goswami’s state of science with respect to education review as part of the Foresight Mental Health and Wellbeing project (Recap of Mental Capital and Wellbeing report 2008): Educational Promise of Neuroscience. 1. An understanding of the neural basis of the mental representations important for effective education (e.g. for literacy and numeracy); 2. The discovery of neural markers for educational risk, which can be measured at any age using passive processing paradigms (i.e. without attention); 3. The evaluation of debates in education that have been difficult to resolve on the basis of behavioural data. Why Neuroscience Matters for Education Biomarkers of brain development can act as markers of learning development. E.g. atypical auditory development found in developmental dyslexia 5. EEG (electroencephalography – measurement of residual brain activity at the scalp) on 5 year olds and adults showed magnitude information associated with numbers was activated equally rapidly in both groups. However, the children took three times as long as the adults to organise their task-relevant responses6. Further neuroimaging results suggest executive resources controlling behaviour are taxed to a much larger extent in children than in adults during the processing of numerical information7. Taken together, these results suggest that the eeg signal could act as a marker to compare children with processing difficulties separately from associated motor behaviour in numerical tests. Educational Myths perpetuated by popular media: Fish oils improve Brain Function: Definitive scientific evidence on this is scarce8. Learning strategies should be tailored towards left/right brain learning or visual/auditory/kinaesthetic strategies depending on the individuals’ optimal style of learning. Howard-Jones comments that commercial exercise packages concepts and explanations are unrecognisable to neuroscientists9. 5 Goswami, U., Thomson, J., Richardson, U., Stainthorp, R., Hughes, D., Rosen, S. and Scott, S.K. 2002. Amplitude envelope onsets and developmental dyslexia: a new hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99:10911-10916. 6 Temple, E. and Posner, M.I. 1998. Brain mechanisms of quantity are similar in 5-year-old children and adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 95:7836-7841. 7 Szűcs, D. Soltész, F., Jármi, E. and Csépe V. 2007. Event-related potentials reveal the contribution of immature executive functions to processing arithmetic information in children. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 3:23 8 Goldacre, B. 2006. The fish oil files. The Guardian, 16 September 2006. See http://www.guardian.co.uk/ science/2006/sep/16/badscience.uknews 9 Howard-Jones, P. 2007. Neuroscience and Education: Issues and Opportunities. Commentary by the Teaching and Learning Research Programme. London: TLRP. General conclusions were that current neuroscience had little to translate to classroom practice. Greatest potential was in longitudinal brain imaging studies to measure mental representations in typically developing brains10, deepening understanding of plasticity and learning, and identification of neural markers or risks in development. Health Professor Theresa Marteau has a background in social and clinical psychology. She is the director of Behaviour and Health Research Unit in Cambridge funded by the Department of Health (2010-2015), officially launched in April 2011. The aim of the centre is to impact on four areas of health: diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption, which together are responsible for the majority of premature deaths worldwide. Expertise to tackle these issues within the Unit, include behavioural economics, anthropology, sociology, neuroscience and social psychology as well as epidemiology and public health. Of the 21 team members listed, one explicitly uses neuroscience techniques (brain imaging) to study emotional links to food. Obesity11 • • • • • • • No single brain area involved. Deficiency of the hormone leptin as a result of mutated gene led to obesity in rare cases. Brain scans of leptin deficient participants showed more activity in striatum when shown images of appetizing foods. A whole host of other chemicals involved in signaling satiety in the brain. Fatty foods tap pleasure centres of the brain, as do heroin and cocaine habits. Rats fed a high calorie, high fat diet showed less response in the brain pleasure centres over time. Addressing obesity requires changes across a range of themes, with environmental, behavioural, chemical and genetic components currently being researched. Economic • New economic theories are emerging showing that in a free market, individuals do not act rationally to optimize benefit. A number of characteristic traits have emerged such as ‘loss aversion’- people show greater sensitivity to losses than to equivalent gains in decision making. Szűcs, D. and Goswami, U. 2007. Educational neuroscience: Defining a new discipline for the study of mental representations. Mind, Brain and Education, 3:114-127. 11 http://www.sfn.org/skins/main/pdf/rd/Obesity.pdf 10 Neural loss aversion in ventral striatum correlated with behavioural loss aversion12. • ‘Too many jams’ study demonstrates that too many investment choices create confusion that leads to inaction13. Testosterone levels indicate success in short term trades. ‘winner effect’ – increasing success increases testosterone levels to eventual irrational risk taking. Driving market volatility. Cortisol levels are marker of performance uncertainty As markets become more volatile, cortisol levels in individuals may increase. High cortisol decreases risk taking behaviour – exaggerating market downturns.14 Figure 2: Standard deviation of Profit and Loss increases with cortisol mean levels (top) and standard deviation levels (bottom), showing that financial uncertainty is directly correlated with cortisol levels. Professor Wolfram Schultz studies reward mechanisms in the brain and relates this to behaviour. His main expertise has been in neurophysiology, recording single neuron activity in monkeys. He also collaborates with groups that perform functional magnetic resonance imaging to corroborate animal findings in the human brain to a degree. He has written a review titled ‘Neuroeconomics: the promise and the profit’, which looks at how decisions about gains and losses are controlled by an individual’s brain activity. He will likely talk about this at the roundtable. Professor Nick Chater has worked on a number of probabilistic models of reasoning and applied these to human experiments in order to explain behaviour. He applies his expertise to the company he founded ‘Decision Technology’, a research consultancy dedicated to the study of human decision-making and the development of any associated practical and commercial applications. 12 Sabrina M Tom, Craig R Fox, Christopher Trepel, Russell A Poldrack (2007). The neural basis of loss aversion in decision-making under risk. Science 315 (5811) p. 515-8 13 Sheena Iyengar, The Art of Choosing (New York, 2010) 14 J. M. Coates and J. Herbert (2008). Endogenous steroids and financial risk taking on a London trading floor. PNAS. 105(16), p 6167-6172. French Policy The Strategic Analysis Centre (Centre d’analyse stratégique) At the request of the Prime Minister of France, The Strategic Analysis Centre provides forecasts for major governmental reforms. On its own initiative, it also carries out studies and analysis as part of an annual working program. A report commissioned by the Director of the Centre, Vincent Chiriqui, supervised by Olivier Oullier and Sarah Sauneron. Titled, ‘Improving public health prevention with behavioural, cognitive and neuroscience research.’ Was published in 2010. It originates from discussions conducted at the centre in 2009 leading to a workshop in June 16th 2009. Produced in collaboration with French and international researchers, including Cary Cooper at the University of Lancaster and others in marketing, neuroscience, psychology and behavioral economics. It appears to be similar to the Foresight project reports although shorter in timescale and scope. It focusses on smoking, domestic poisoning incidents and obesity under the following headings. Major areas of report: Public Health Prevention beyond rational decision making. o Most efficient prevention strategies o Changing behaviours in chronic disease prevention o Improving health with nudge o Consumer neuroscience o Effectiveness of prevention campaigns Toxic Substances o Evaluation of current cessation of smoking campaigns o Neuroscience and smoking prevention Obesity o Political priority o Information and education strategies o Neuroscience and obesity o Mental Capital and Wellbeing (2008) Aim: The aim of the Foresight Project on Mental Capital and Wellbeing has been to advise the Government on how to achieve the best possible mental development and mental wellbeing for everyone in the UK in the future. The Project has used the best available scientific evidence to develop a vision for: the opportunities and challenges facing the UK over the next 20 years and beyond, and the implications for everyone’s mental development and mental wellbeing; signposts to what we all need to do to meet the challenges ahead – Government, individuals and business. Project Oversight: John Denham MP, Secretary of State, received the Project on behalf of the Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills. Bill Rammell MP, formerly Minister of State for Lifelong Learning, Further and Higher Education sponsored the Project and chaired the Project High Level Stakeholder Group. Professor John Beddington, the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Government was the Project Director. Professor Cary Cooper CBE, pro-vice-chancellor at the University of Lancaster, chaired the Project's Science Co-ordination team.