- Ethno Arts

advertisement

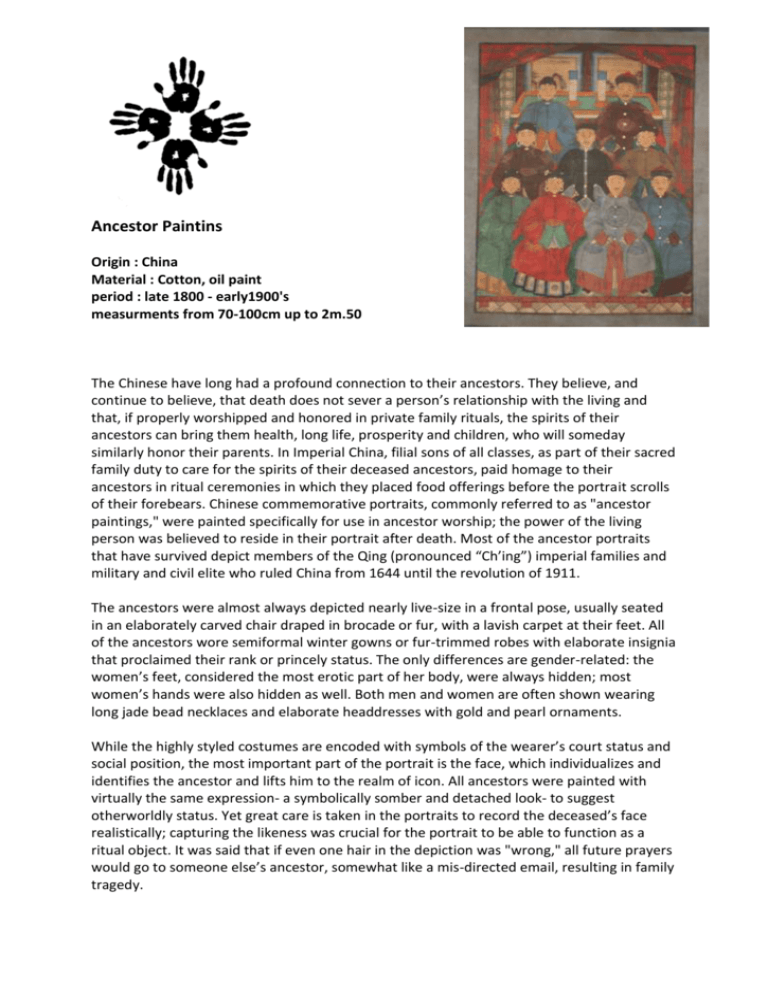

Ancestor Paintins Origin : China Material : Cotton, oil paint period : late 1800 - early1900's measurments from 70-100cm up to 2m.50 The Chinese have long had a profound connection to their ancestors. They believe, and continue to believe, that death does not sever a person’s relationship with the living and that, if properly worshipped and honored in private family rituals, the spirits of their ancestors can bring them health, long life, prosperity and children, who will someday similarly honor their parents. In Imperial China, filial sons of all classes, as part of their sacred family duty to care for the spirits of their deceased ancestors, paid homage to their ancestors in ritual ceremonies in which they placed food offerings before the portrait scrolls of their forebears. Chinese commemorative portraits, commonly referred to as "ancestor paintings," were painted specifically for use in ancestor worship; the power of the living person was believed to reside in their portrait after death. Most of the ancestor portraits that have survived depict members of the Qing (pronounced “Ch’ing”) imperial families and military and civil elite who ruled China from 1644 until the revolution of 1911. The ancestors were almost always depicted nearly live-size in a frontal pose, usually seated in an elaborately carved chair draped in brocade or fur, with a lavish carpet at their feet. All of the ancestors wore semiformal winter gowns or fur-trimmed robes with elaborate insignia that proclaimed their rank or princely status. The only differences are gender-related: the women’s feet, considered the most erotic part of her body, were always hidden; most women’s hands were also hidden as well. Both men and women are often shown wearing long jade bead necklaces and elaborate headdresses with gold and pearl ornaments. While the highly styled costumes are encoded with symbols of the wearer’s court status and social position, the most important part of the portrait is the face, which individualizes and identifies the ancestor and lifts him to the realm of icon. All ancestors were painted with virtually the same expression- a symbolically somber and detached look- to suggest otherworldly status. Yet great care is taken in the portraits to record the deceased’s face realistically; capturing the likeness was crucial for the portrait to be able to function as a ritual object. It was said that if even one hair in the depiction was "wrong," all future prayers would go to someone else’s ancestor, somewhat like a mis-directed email, resulting in family tragedy.