translation

advertisement

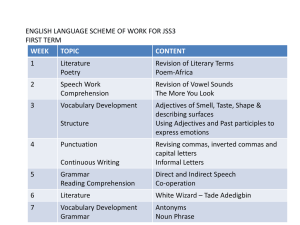

Emily Cho ENGL 392B Dr Sylvia Söderlind November 24, 2003 Lost in Translation Traduttore, traditore. All English translations of Chinese poetry betray the structure if not the essence of the original works. As Roman Jakobson noted, poetry is untranslatable and “only creative transposition is possible” (238). Even so, with its exacting demands on concision, ambiguity, and structure, Chinese poetry is difficult to transpose intralingually. Between Chinese and English, there is the additional hurdle of untranslatable signs. Is it possible then to transpose these poems interlingually? The Chinese language is made up of monosyllabic characters, and each character has a fixed tone. There are five tones in the Chinese written language (i.e. Mandarin). The first two tones are “even tones” and the last three are “uneven tones.” One can already see the dangers in trying to translate Chinese poetry into English: the sign – or more appropriately in this case, “sound-image” – is vastly different. In English, each sound-image may consist of more than one syllable, and its tone may affect the emotive function but usually not its inherent meanings. There are four types of Chinese poetry: shi (“poetry proper”), ci (“songs that have lost their tunes”) , ge (songs) , and fu (prose poetry). Here, we will examine shi, which consists of three forms: lü shi (code verse), gu shi (old poetry), and jue ju (frustrated verse). All shi have the same number of characters – usually five, six, or seven – in each line. Code verses contain two or more parallel couplets. By “parallel”, it is meant that there is not only a parallelism in content, but also in tones, allusions, and parts of speech. A character with an “even tone” must be paired with a character with an 2 “uneven tone” in the same position in the next line. Nouns are paired with nouns, verbs with verbs, adjectives with adjectives, and so forth. If a certain type of noun – for example, an animal – is mentioned in one line, another noun denoting an animal is used in the corresponding line to “balance” the couplet. Parallelism is sometimes used in English poetry, but never to the excess of Chinese poetry. It is therefore challenging if not impossible for an English writer to match this art of balance in his or her translation of a Chinese poem. Old poetry (gu shi) is liberal with the tonal order within a line, and it uses parallelism mainly to enhance a particular mood. The frustrated verse has four lines of five or seven syllables each and is used to create a mood and not a story. Li Bai (701-762 A.D.) wrote a gu shi called “Jìng Yè Sī” (“Thoughts on a Still Night”): Literally, word by word, it is translated as: Bed before bright moon shine Think be ground on frost Raise head view bright moon Lower head think home (Bai, n.d.) Chinese syntax differs from that of English, as is evident from the first two lines. When read through the lenses of English syntactic rules, the “bed” in line 1 appears to be the subject, even though the verb “shine” – like all other verbs in Chinese – is not conjugated and therefore cannot clearly denote what is shining. This ambiguity makes Chinese poems effortful to translate. Bynner translates line 1 as: “So bright a gleam on 3 the foot of my bed” (2000). In the original poem, Li Bai states that the moonshine appears before – or at the head of – the bed. Why does Bynner use the phrase “the foot of”? Can this be a culturally influenced use of diction? Or is this an example of “our ignorance of Chinese psychology” (Fang 133)? In Chinese, the notion of “foot of the bed” does exist, but Li Bai chooses “before” or “head of” the bed. Upon closer examination of Bai’s poem, we see that the word “head” is mentioned in the last two lines. The popular use of parallelism in Chinese poetry is at work here. Furthermore, the Chinese word for “back” – hòu – does not fit into the tonal pattern of the poem, so it is not used by Bai. Bynner’s “a gleam” is an interesting word choice. Does it serve a higher poetic function than “moonshine”? After all, the word “moon” is mentioned in the first and third lines of the original poem. Let us examine how Bynner translates the rest of the poem: So bright a gleam on the foot of my bed -Could there have been a frost already? Lifting myself to look, I found that it was moonlight. Sinking back again, I thought suddenly of home. (Bynner 2000) Bynner mentions “moonlight” in line three. Thus, his earlier use of “a gleam” creates suspense in the poem – an atmosphere that Bai did not intend for his poem. In Bynner’s translation, the tenses are evident. Not so in Bai’s poem. Because it does not have tensed verbs, the Chinese language relies heavily on adverbs such as “today”, “right now”, or “yesterday”. Lacking adverbs, Bai’s poem is ambiguous in terms of tenses. Does it matter if Bai’s poem is set in the past, the present, or the future? It is Bai’s intention to capture the fleeting scene of a moonlit bedroom which stirs within the narrator a sense of nostalgia. This idea – this feeling – of nostalgia cannot and should not be trapped by time. 4 The narrative should be in harmony with the narration. By using past tense in his translation, Bynner erodes the sense of urgency in “Jìng Yè Sī”. Li Bai’s poem does not have punctuation, yet it is effective in conveying its message. What makes it so? Can it be the high poetic function of its word choices? Or the emotive values of its tones and rhymes? Or maybe it is because of the deceivingly simple references painted by Bai? Since poetry is a complex form of literature, it is safe to say that its effectiveness stems from the combination of all of the aforementioned factors. In translating “Jìng Yè Sī”, Bynner has added punctuation to the poem. He has turned line two into the form of a question. This is a clever way of avoiding a literal translation of the word “yí”, because “yí” is a sign that cannot truly be translated into English. “Yí” suggests anxiety, suspicion, and doubt. This, however, is not linked to the earlier suspense that Bynner tried to evocate. Instead, “yí” is related to mild confusion. Nevertheless, Bynner’s addition of the pause and the question mark in lines one and two supplement Bai’s intention that his poem be about thinking and nostalgia. In return, Bai’s punctuation-less poem allows Bynner free rein in his interpretation of “Jìng Yè Sī”. To “translate a poem whole is to compose another poem. A whole translation will be faithful to the matter, and it will “approximate the form” of the original; and it will have a life of its own which is the voice of the translator”(Mathews 67). Bynner’s voice certainly rings clearly, but Bai’s voice is drowned in rynner’s translation. The referential function – the matter – remains somewhat similar in the two poems, but with the translation of codes – interlingual and poetic – the emotive and poetic functions are lost. Benjamin believes that words have “emotional connotations” and that “a literal rendering of the syntax completely demolishes the theory of reproduction of meaning and is a direct 5 threat to comprehensibility”(78). Bynner did not render Bai’s syntax literally, but the emotional connotations are diluted from the original poem because of the poorer word choices and the unravelling of the poetic structure. The poetic structure is the skeleton of the poem. Without it, there is no poetic art. Bynner could well have written a prose paraphrase of “Jìng Yè Sī” if poetic devices do not matter. Because the translator is bound to fail at reproducing Chinese metre, he does not attempt this feat. Nonetheless, is he not a traitor for draining the essence from the original poem in his re-creation of it? Mathews responds thus: “Yet the final test of a translated poem must be does it speak, does it sing?”(68). Does Bynner’s translation of Bai’s poem speak? Does it sing? This is arguable. Nontheless, Yefei He’s translation of Meng Haoran’s (689-740 A.D.) lü shi “Chūn Xiăo” (“Spring Dawn”) certainly sings: How suddenly the morning comes in Spring! On every side you hear the sweet birds sing. Last night amidst the storm -- Ah, who can tell, With wind and rain, how many blossoms fell? (He 1999) He’s translation is lively and takes on a life of its own. Although it does not follow the strict poetic form of Meng Haoran’s original poem – two parallel couplets with five characters each – his translation does adhere to the English poetic code. Rhyming in aabb form, He’s poem makes good use of word choice and of the phatic function. His interpretation is an act of poetry. Compare it to Meng Haoran’s original poem: 6 which translates literally, word for word, thus: Spring sleep not wake dawn Everywhere hear cry bird Night come wind rain sound Flower fall know how many (Haoran n.d.) Like Li Bai’s “Jìng Yè Sī”, Meng Haoran’s “Chūn Xiăo” is in aaba form. This differs from He’s rhyme scheme but this does not matter because He managed to capture the essence of Haoran’s poem. The Chinese syntax in “Chūn Xiăo” is dramatically different from English syntax, but because He seems to have a strong grasp of both Chinese and English, his translated poem is “destined to become part of the growth of its own language and eventually to be absorbed by its renewal” (Benjamin 73). He has overcome the problem of translation from the three angles that Fang suggested translators should tackle: adequate comprehension of the translated text, adequate manipulation of the language translated into, and what happens in between (111). Du Fu’s (712-770 A.D.) “Chūn Wàng” (“Spring Gaze”) is an exemplary form of lü shi: 7 And it is translated literally thus: Country damaged mountains rivers here City spring grass trees deep Feel moment flower splash tears Regret parting bird startle heart Beacon fires join three months Family letters worth ten thousand metal White head scratch become thin Virtually about to not bear hairpin (Fu n.d.) Written in ababcdcd form, “Chūn Wàng” is also in +-+-+-+- form, where + is “uneven tone”, and - “even tone.” Although this can be mimicked in English through the use of stressed and unstressed syllables, it is very unlikely that the translator can retain the poetic form of five syllables per line. “Chūn Wàng” is also rich in contrasts. The first two lines parallel each other in every way: “country” is contrasted with “city”, “damaged” is contrasted with “spring” (new life), “mountains/rivers” is contrasted with “grass/trees”, and the location “here” is contrasted with the location “deep”. In lines three and four, “flower”/“bird”, “splash”/“startle”, and “tears”/ “heart” are similarly grouped terms. In lines six and seven, the numbers “three” and “ten” are matched. The translator can easily 8 incorporate these contrasting and similar terms into the translated poem, but these terms will not be able to match syllabically. Fang denounces “amateur Sinologists” whose “veneration of dictionaries” tends to lead them “to lose sight of context” (132). For example, in the last line of “Chūn Wàng”, there is an obscure reference to “hairpin.” A translator unversed in Chinese history will not catch the nuance of the word. Hairpins in this poem connote authority: the pins described were used to hold in place the caps worn by Chinese officials. This small but significant fact is essential to the translator’s understanding of the narrative and the narration, which helps the translator in remaining true to the spirit of the poem. Benjamin believes that “the intention of the poet is spontaneous, primary, graphic; that of the translators derivative, ultimate, ideational” (76). Can translators accurately derive the essence – form and substance – from Chinese poetry and faithfully echo these works in English? It appears that this is a daunting task that one can rarely excel at. Benjamin also speculates that “in translation the original rises into a higher and purer linguistic air, as it were” (75). Can this be true? By reading “poor” English translations of Chinese poetry, will the reader hold the original poems in higher regard? Or can these poems stand on their own merits? Despite the betrayal of the translators, Chinese poems can now be enjoyed by a broader audience because of these interlingual translations – or as Jakobson pointed out, “transpositions.” Through these transpositions, Chinese poetry can speak and sing and soar again. 9 WORKS CITED Bai, Li. “Thoughts on a Still Night.” In Chinese Poems. Available: http://www.chinesepoems.com/lb4t.html, date unavailable. Accessed: November 21, 2003. Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Translator.” In Illuminations. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, In., 1968. Bynner, Witte. “In the quiet night.” In eChinaArt.com’s “Post Translation & Rewriting of Tang Poem No.2.” Available: http://www.echinaart.com/news/archive/news_tangpoem_091700.htm, 2000. Accessed: November 20, 2003. Fang, Achilles. “Some Reflections on the Difficulty of Translation.” In the President and Fellows of Harvard College’s On Translation, p. 111-133. Edited by Reuben A. Bower. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966.In the Fu, Du. “Spring View.” In Chinese Poems. Available: http://www.chinesepoems.com/springviewt.html, date unavailable. Accessed: November 21, 2003. Haoran, Meng. “Spring Dawn.” In Chinese Poems. Available: http://www.chinesepoems.com/m9t.html, date unavailable. Accessed: November 21, 2003. He, Yefei. “Meng Hao-jan.” Available: http://www.cs.uiowa.edu/~yhe/poetry/meng_hao_jan_poems.html, 1999. Accessed: November 20, 2003. Jakobson, Roman. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” In the President and Fellows of Harvard College’s On Translation, p. 232-239. Edited by Reuben A. Brower. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966. Mathews, Jackson. “Third Thoughts on Translating Poetry.” In the President and Fellows of Harvard College’s On Translation, p. 67-77. Edited by Reuben A. Bower. New York: Oxford University Press, 1966.