Revised Manuscript

advertisement

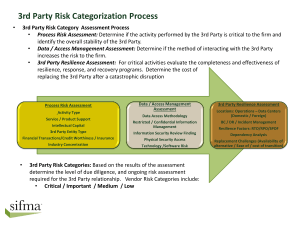

Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression Stress and Depression in University Students: The Mediating Role of Resilience [masked title page] 1 Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 2 Abstract Objective: We examined the extent to which the relationship between adverse stress and depression is mediated by university students’ perceived resilience. Participants: Students were randomly sampled at a Canadian university in 2006 (N = 2,147) and 2008 (N = 2,292). Methods: Data about students’ stress (1 item), depression (4 items), resilience (4 items), and their demographics were obtained via the online National College Health Assessment survey and analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis and latent variable mediation modeling. Results: Greater resilience was associated with lower depression scores for students whose stress impeded their academic performance, irrespective of their sex and age (total R2depression = 40%). The relationship between stress and depression was partially mediated by resilience (37% to 55% mediation depending on the severity of stress). Conclusions: Identifying students with limited resilience and providing them with appropriate supportive services may help them to manage stress and prevent depression. Keywords: resilience, depression, stress, student Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 3 Stress and Depression in University Students: The Mediating Role of Resilience The National College Health Assessment (NCHA), sponsored by the American College Health Association, has collected data about students’ health status, behavior, and attitudes since 2000. The participation has increased annually and in 2007 more than 90,000 students from about 150 postsecondary institutions completed the survey (up-to-date survey participation rates are available at: http://www.acha-ncha.org/partic_history.html). Topics covered via the approximately 300 questions include: risk and protective behavior, health information access, injury and violence prevention, tobacco, alcohol and other substance use, sexual health, nutrition, and mental health. The NCHA is used by many academic institutions to gain information about the status of students’ mental and physical health. This helps inform the planning of student health services and is of interest to nurses who often play an important role in the delivery of these services. Concerns about students’ mental health status have arisen as a result of the data collected and compiled through the NCHA. The percentage of North American students that reported having ever been diagnosed with depression appears to be increasing: 10.3% and 11.8% in the spring surveys of 2000 and 2001, respectively, and 15.3% and 14.9% in spring 2007 and 2008 (The American College Health Association, 2001, 2008, 2009). Of the many risk factors for depression, students’ experience of stress is of particular concern to many college health professionals involved in health promotion and counseling services, including nurses and nurse practitioners. For example, the most frequently reported impediment to academic performance is stress, which out ranks viral infections, sleep disturbances, concerns about family members and friends, and relationship problems (The American College Health Association, 2003, 2009). Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 4 Given the evidence indicating that an association exists between the experience of stress and subsequent risk for major depressive episodes in adults (Hammen, 2005; Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999; Kessler, 1997), researchers have sought to examine the causes and consequences of stress experienced by university students. Students must manage multiple demands including the transition from adolescence to adulthood, adapting to a new environment, establishing new social networks, independently managing the demands of daily life, and meeting their personal goals. Although these potentially stressful transitions are expected, they can contribute to symptoms of depression (Dyson & Renk, 2006). Whereas reducing the number and intensity of stressors experienced by students might be viewed as the most efficient means of improving the mental health of students, recent research about resilience indicates that the experience and successful management of stress represent a critical component of adolescent development (Campbell-Sills, Cohan, & Stein, 2006; Haglund et al., 2009; Nrugham, Holen, & Sund, 2010; Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008). The scientific literature contains several definitions of resilience offered by researchers working in a wide variety of socio-cultural settings and with populations ranging from adult Holocaust survivors to children living in extreme poverty. For example, in their research on the development of competence in children and adolescents, Masten and Coatsworth (1998) defined resilience as “manifested competence in the context of significant challenges to adaptation or development” (p. 206). Similarly, resilience has been defined as “the positive counterpart[s] to both vulnerability, which denotes an individual’s susceptibility to a disorder, and risk factors” (Werner & Smith, 1992, p. 3), and as “a dynamic process wherein individuals display positive adaptation despite experiences of significant adversity or trauma” (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000, p. 543). Luthar et al. elaborated that there are “two critical conditions: (1) exposure to Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 5 significant threat or severe adversity; and (2) the achievement of positive adaptation despite major assaults on the developmental process” (Luthar et al., 2000, p. 543). Resilience, then, can be conceptualized as a process as well as a personal characteristic that can be developed over time and in response to the exposure to and subsequent effects of stressors (sometimes referred to as the “steeling effect”) (Rutter, 2006). These conceptual foundations suggest that the experience of stress and its consequences can either enhance or constrain the development of resilience. For example, in college or university students, stress can affect academic performance (e.g., students may withdraw from or fail a course), and consequently can contribute to a more general perceived inability to manage stress (i.e., reduced resilience). Students with limited resilience are vulnerable to adverse psychological outcomes including depression. In the context of statistical modeling, this intervening role of resilience can be represented as a mediating effect of the relationship between adverse stress and depression (see Figure 1). The purpose of our investigation was to examine the plausibility that resilience is a mediator of the relationship between adverse stress (as manifested through its reported effect on academic performance) and depression, and, if so, to quantify the degree of mediation. Method Participants The data were obtained via one Canadian university’s spring 2006 and 2008 NCHA surveys. This university administers the full NCHA survey every two years and adds a few university-specific questions, including items to measure resilience, disabilities, and Canadianrelevant indicators of ethnicity. Students were randomly selected within three strata: (a) undergraduate students at Campus I, (b) graduate students at Campus I, and (c) undergraduate Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 6 and graduate students combined at Campus II. In addition, all international students and students living in residence at Campus I were invited to complete the questionnaires. All analyses were first conducted with the 2006 data and subsequently validated with the 2008 data. The results presented here are for 2006 data unless otherwise stated. Ethical approval was provided by the university’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board. The students at the two campuses were invited via email to participate in the web-based survey. Invited students received information about the purpose and content of the survey, the expected time required, how privacy would be protected, and referrals to health services. They were informed that by accessing the survey website their consent to participate was inferred. Measures The NCHA questionnaire includes seven items measuring depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation and attempts. The respondents were asked to indicate the number of times, within the last school year, they had: (a) “felt things were hopeless,” (b) “felt overwhelmed by all you had to do,” (c) “felt exhausted (not from physical activity),” (d) “felt very sad,” (e) “felt so depressed that it was difficult to function,” (f) “seriously considered attempting suicide,” and (g) “attempted suicide.” The response options were: (a) “never,” (b) “1-2 times,” (c) “3-4 times,” (d) “5-6 times,” (e) “7-8 times,” (f) “9-10 times,” and (g) “11 or more times” (coded as 1 to 7, respectively). Researchers have used these items as an index to compare levels of depressive symptomology across groups of students (e.g., men vs. women, younger vs. older students, oncampus vs. off-campus residents, fraternity/sorority members vs. not) (Office for Survey Research, 2002). However, the construct validity of these items as a unidimensional measure of depression has not been shown. Other researchers have used only some of the items to measure depression. For example, Adams, Moore, and Dye (2007) conducted a principal components Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 7 analysis of five of the indicators (items a-e) and produced a 3-item scale (items a, d, and e). Considering the limited evidence of measurement validity, we conducted a psychometric analysis with the 2006 data to determine whether the 7 depression items could be represented by a single factor. We found support for a model with 4 items (a, d, e, f), which was validated via a multi-group CFA, using the 2008 data, with the loadings, thresholds and variances constrained to be equal across the two study periods (further described in the Results). The academic consequences resulting from stress were inferred from one of the 25 potential impediments to academic performance enumerated in the NCHA questionnaire. The respondents were prompted to select one of the following five options to indicate whether stress had adversely affected their academic performance: (a) “this [stress] did not happen to me/not applicable,” (coded as “0”) (b) “I have experienced this issue [stress] but my academics have not been affected,” (coded as “1”) (c) “received a lower grade on an exam or important project,” (coded as “2”) (d) “received a lower grade in the course,” (coded as “3”) and (e) “received an incomplete or dropped the course” (coded as “3”). Response options (d) and (e) were collapsed and response option (a) served as the referent in the dummy variable, which was created to accommodate the ordinality of the measure. Four resilience indicators were developed by one of the authors (CW), a registered psychologist and director of university counselling services. These indicators were derived from the work of Lazarus and Folkman (1984), which was based on the theory that the experience of stress is a product of an individual’s evaluation of the importance of a stressor combined with the perceived ability to cope with the stressor. Based on this theory and the notion of resilience as an evolving characteristic, students’ perceived ability to recognize and manage their stress is conceptualized as reflective of resilience to stress and reduces the extent to which stress Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 8 contributes to the onset of depression. The items are: “Please indicate the degree to which the following statements are true: (a) I believe I have the ability to cope with the demands of my life, (b) I know when I’m starting to experience too much stress, (c) I know how to cope with stress when it comes, and (d) I am usually able to successfully deal with my stress levels.” Responses were labeled: “agree strongly,” “agree somewhat,” “disagree somewhat,” or “disagree strongly” (coded as “1” to “4,” respectively). These items were reverse coded in the statistical models such that a higher score was indicative of more resilience. A one-factor CFA was conducted to examine the measurement validity of these items with the 2006 data, and a validation assessment was carried out using the 2008 data (see Results for further information). Age was represented as three categories that were dummy-coded: less than or equal to 20 years (referent, coded as “0”), greater than 20 and less than or equal to 30 years, and greater than 30 years. Sex was represented as a binary variable (female coded as “1”). Analytical Approaches Frequency distributions were produced for each of the observed variables. A latent variable mediation model (Mackinnon, 2008) was specified to examine the relationships among the variables, academic consequences of stress, depression, and resilience, as shown in Figure 1, while controlling for age and sex (not shown in the figure). Depression and resilience were specified as latent variables with one of the loadings for each variable fixed at one for purposes of identification. The manifest, polytomous variable, academic consequences of stress, along with age and sex, were specified to directly affect depression and to indirectly affect it through the mediating variable, resilience. The indirect effect of academic consequences of stress on depression, via resilience, was calculated as the product of the coefficients of these relationships (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). The estimation of the indirect Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 9 effects for the three levels of academic consequences of stress was done simultaneously in the latent variable mediation model. Similar to the commonly used Sobel (1990) test (which tests whether a mediator carries an effect from an explanatory variable to an outcome variable), the delta method was used to estimate the standard errors of the indirect effects (Mackinnon & Dwyer, 1993). For each level of academic consequences of stress, the percent mediation was determined by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect (the sum of the indirect and direct effects) (Mackinnon, 2008). The MPlus 5.2 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2008) was used to conduct exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the latent variable measurement models, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted to estimate the parameters of the mediation model. Two-group SEM (Schumacker & Lomax, 2010) was conducted with the 2006 and 2008 data to validate the consistency of the measurement model parameters across the two years. We applied mean and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation (WLSMV) to accommodate the ordered categorical data (Finney & DiStefano, 2006). Model fit was assessed by scrutinizing the residual correlations and the model fit indices. Indicators suggestive of acceptable fit included: a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of less than .06 and a comparative fit index (CFI) greater than .95 (Beauducel & Herzberg, 2006). Results Sample Description Of 11,781 randomly sampled undergraduate and graduate students registered at the two campuses, 2,147 (18.2%) completed the questionnaire in 2006. In 2008, 11,490 students were randomly sampled and 2,292 (20.0%) completed the questionnaire. A comparison of demographic characteristics of the samples and the corresponding populations is provided in Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 10 Table 1. The sample shows over representation of females, full-time students and graduate students. The frequency distributions of the seven depression items and four resilience items are provided in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. Almost all students responded to the academic consequences of stress item (n = 2,103): 38% reported experiencing stress that affected their academic performance (25% reported a lower grade on an exam/project and 13% reported a lower course grade or an incomplete/dropped course); 44% experienced stress that did not affect their academic performance; and 16% reported experiencing no stress. Psychometric Analyses In establishing the measurement structure for the seven depression items, we first excluded “item g” (attempted suicide) because only 1.3% of the respondents answered affirmatively. The remaining six items were included as ordinal variables in a one-factor CFA. This model did not fit well (WLSMV χ2(6) = 589.8, RMSEA = .216, CFI = .955). The results of a subsequent EFA indicated that a two-factor solution would provide better fit to the data. We then conducted a two-factor CFA with items a, d, e, and f loading on factor 1 (these items were interpreted as indicative of depression) and items b and c loading on factor 2 (overwhelmed or exhausted). The fit of this model was significantly better than the one-factor CFA model (∆WLSMV χ2(1) = 311.6, WLSMV χ2(6) = 72.3, RMSEA = .073, CFI = .995). Factor 2 was omitted from further analyses because of its non-specificity. The one-factor CFA of the remaining four items (a, d, e, f) resulted in good model fit (WLSMV χ2(2) = 15.5, RMSEA = .057, CFI = .999). The ordinal alpha coefficient of reliability (Zumbo, Gadermann, & Zeisser, 2007) for the four items was .92, with standardized factor loadings ranging from .78 to .91. The validation of this model (with 2008 data) provided evidence of parameter invariance across the two study periods (WLSMV χ2(8) = 29.7, RMSEA = .035, CFI = .999). Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 11 A 1-factor CFA of the four resilience items resulted in a well-fitting model (WLSMV χ2(2) = 17.8, RMSEA = .061, CFI = .999). The standardized factor loadings ranged from .43 for item b (“I know when I’m starting to experience too much stress”) to .92 for item d (“I am usually able to successfully deal with my stress levels”). The ordinal alpha coefficient was .86. Evidence of parameter invariance was shown in the validation assessment with the 2008 data, when the parameters were constrained to be equal across the two years (WLSMV χ2(8) = 12.6, RMSEA = .016, CFI = 1.000). Structural Equation Model The mediation model as shown in Figure 1 resulted in acceptable fit (WLSMV χ2(32) = 248.3, RMSEA = .057, CFI = .982). Similar results were obtained when the model was validated with the 2008 data by constraining the measurement model parameters (loadings and thresholds) and the structural parameters to be equivalent across the two study periods (WLSMV χ2(60) = 409.59, RMSEA = .052, CFI =.986). The 2006 model explained 40% of the variance in depression and 23% of the variance in resilience. Depression was significantly explained by academic consequences of stress and resilience but not by the covariates of age and gender; a relative increase in the consequences of stress and a decrease in resilience were associated with greater depression scores. Resilience was significantly explained by academic consequences of stress and by the covariates of age and gender; a relative increase in academic consequences of stress was associated with reduced resilience, students in the oldest age group had greater resilience scores relative to those in the youngest age group, and female students had lower resilience scores compared with male students’ scores. The effect of stress on depression was partially mediated by resilience. That is, the degree to which the academic consequences of stress influenced depression could be partially attributed Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 12 to the respondents’ reported resilience. Relative to “no stress” (the referent), 37% of the total effect of “stress that does not affect academic performance versus no stress” on depression was mediated by resilience. The percentages of mediation were 55% for “stress resulting in a lower grade on an assignment or project” and 51% for “stress resulting in a lower or incomplete course grade versus no stress.” The corresponding indirect, direct and total effects are reported in Table 2. Discussion The mediation model presented here was found to be a plausible explanation of the relationships among the variables of interest. Similar to other published literature, we found that the stress students experience is directly related to increased levels of depressive symptoms. In addition, we found that a substantial portion of this relationship appears to be mediated through students’ perceived ability to recognize and manage their stress (i.e., their resilience) when the stress is an impediment to academic performance. Approximately one half of the relationship between stress and depression was mediated through the resilience of students whose stress affected their academic performance. The latent variable approach used for the measurement of depression and resilience is both a strength and limitation of this study. We undertook a rigorous psychometric evaluation of the items with particular attention paid to the ordinal nature of the response options thereby accounting for some sources of measurement error. The results of the psychometric analyses of the depression items suggest that significant error would have been unaccounted for if an index of depression were to be used based on the summed responses to these items. We recommend that researchers use a relatively sophisticated data analytic approach based on a latent variable single factor structure of the four relevant items identified in our analyses. With respect to the Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 13 resilience items, it is acknowledged that they have not been used or examined in other studies so far, and therefore require further examination of their validity. A further limitation arises from the cross-sectional nature of the survey data; any implied causal inferences must be interpreted with caution and other plausible models exist. In addition, the low response rate raises concerns about the representativeness of the sample. Nevertheless, these limitations are partially mitigated by having replicated the analyses in another sample (i.e., in two time periods). Relative to the population, female and full-time students were overrepresented in the sample. This pattern is commonly found in university-based voluntary surveys. The extent to which this overrepresentation biases the conclusions is unknown. The field would be advanced further by the availability of prospective studies about resilience development in students. The finding of the substantial mediating effect of resilience is congruent with the work of others in the field. Although not examined in the current study, it is hypothesized that, through the development of resilience, students could learn to effectively recognize and cope with the stressors that they encounter and, in so doing, avoid transitioning into states of depression (Schaefer & Moos, 1992). Resilience development refers to the notion that low to moderate levels of stress exposure provide students with the opportunity to practice coping skills (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Conversely, the inability to cope with even low to moderate levels of stress could impair the development of resilience and thereby increase vulnerability to depression. An important implication relevant for nurses and other health professionals involved in college health promotion is that interventions focused on developing resilience may reduce the risk of depression. Specifically, although potentially stressful transitions are expected in university students, referrals to and the provision of counselling services that focus on enhancing Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 14 students’ resilience, may help to mitigate undesirable consequences of stress and reduce the risk of depression. Stress is ubiquitous and many students may require support in developing resilience. Rather than focussing all efforts on removing stressors, programs designed to enhance students’ ability to cope are needed. For example, research has shown that active coping (seeking social support, reframing stressors in a positive light) is associated with improved well-being, fewer psychological symptoms, and the ability to manage stressful circumstances (Valentiner, Holahan, & Moos, 1994). Promising programs have been developed for both school-aged children and university or college students to develop their ability to cope with stress (Gillham, Hamilton, Freres, Patton, & Gallop, 2006; Steinhardt & Dolbier, 2008). Identifying students with limited resilience and providing them with appropriate supportive services may help them to manage stress and thus prevent it from impeding their academic performance. Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 15 References Adams, T. B., Moore, M. T., & Dye, J. (2007). The relationship between physical activity and mental health in a national sample of college females. Women & health, 45(1), 69-85. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n01_05 Beauducel, A., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2006). On the performance of maximum likelihood versus means and variance adjusted weighted least squares estimation in CFA. Structural Equation Modeling, 13, 186-203. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1302_2 Campbell-Sills, L., Cohan, S. L., & Stein, M. B. (2006). Relationship of resilience to personality, coping, and psychiatric symptoms in young adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(4), 585-599. doi: doi:10.1016/j.brat.2005.05.001 Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(10), 1231-1244. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20295 Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399-419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling: A second course (pp. 269-314). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. Gillham, J. E., Hamilton, J., Freres, D. R., Patton, K., & Gallop, R. (2006). Preventing depression among early adolescents in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled study of the Penn Resiliency Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 34(2), 203-219. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9014-7 Haglund, M. E., aan het Rot, M., Cooper, N. S., Nestadt, P. S., Muller, D., Southwick, S. M., & Charney, D. S. (2009). Resilience in the third year of medical school: A prospective study of the associations between stressful events occurring during clinical rotations and student well-being. Academic Medicine, 84(2), 258-268. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819381b1 Hammen, C. (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293-319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 Kendler, K. S., Karkowski, L. M., & Prescott, C. A. (1999). Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(6), 837-841. Kessler, R. C. (1997). The effects of stressful life events on depression. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 191-214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.191 Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543-562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164 Mackinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Mackinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144-158. doi: 10.1177/0193841X9301700202 Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 16 MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83-104. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.83 Masten, A. S., & Coatsworth, J. D. (1998). The development of competence in favorable and unfavorable environments. Lessons from research on successful children. American Psychologist, 53(2), 205-220. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.53.2.205 Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2008). MPlus (version 5.2). Los Angeles, CA: Statmodel. Nrugham, L., Holen, A., & Sund, A. M. (2010). Associations between attempted suicide, violent life events, depressive symptoms, and resilience in adolescents and young adults. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(2), 131-136. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43a2 Office for Survey Research. (2002, June 27, 2011). The Health of MSU Students: 2002 Mental and Emotional Health. Retrieved June 20, 2010, from http://www.ippsr.msu.edu/NCHA/Results.htm#Snapshot Rutter, M. (2006). Implications of resilience concepts for scientific understanding. In B. M. Lester, A. S. Masten & B. McEwen (Eds.), Resilience in Children (Vol. 1094, pp. 1-12). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Schaefer, J., & Moos, R. (Eds.). (1992). Life crises and personal growth. Westport, CT: Praeger. Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. Sobel, M. E. (1990). Effect analysis and causation in linear structural equation models. Psychometrika, 55(3), 495-515. doi: 10.1007/BF02294763 Steinhardt, M., & Dolbier, C. (2008). Evaluation of a resilience intervention to enhance coping strategies and protective factors and decrease symptomatology. Journal of American College Health, 56(4), 445-453. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.44.445-454 The American College Health Association. (2001). Reference group data report: Spring 2001. Baltimore: American College Health Association. The American College Health Association. (2003). Two More Data Sets Enhance Survey's Overview of the Health Status of College Students (Vol. 2003). Baltimore: American College Health Association. The American College Health Association. (2008). American College Health Association National College Health Assessment spring 2007 reference group data report (abridged). Journal of American College Health, 56(5), 469-479. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.469-480 The American College Health Association. (2009). American College Health Association National College Health Assessment Spring 2008 Reference Group Data Report (abridged). Journal of American College Health, 57(5), 477-488. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.477-488 Valentiner, D. P., Holahan, C. J., & Moos, R. H. (1994). Social support, appraisals of event controllability, and coping - an integrative model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(6), 1094-1102. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.6.1094 Werner, E. E., & Smith, R. S. (1992). Overcoming the odds: High risk children from birth to adulthood. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Zumbo, B. D., Gadermann, A. M., & Zeisser, C. (2007). Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for Likert rating scales. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods, 6, 2129. Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 17 Table 1 Sample and Population Distributions 2006 2006 2008 2008 Sample Population Sample Population (N = 2,147) (N=49,683) (N = 2,292) (N=50,706) Gender Female 67% 57% 67% 56% Male 32% 43% 32% 46% 2% - 1% - 92% 67% 88% 69% No 6% 33% 10% 31% Missing 2% - 1% - 16% 17% 16% 18% 2nd year undergrad 15% 15% 15% 16% 3rd year undergrad 16% 19% 15% 20% 4th year undergrad 11% 18% 11% 17% 5% 5% 6% 5% 34% 20% 34% 18% adult special / other 1% 6% 2% 5% Missing 3% - 2% - Age 18 - 20 33% 30% 32% 31% 21 - 29 46% 51% 48% 50% 30 - 68 19% 20% 19% 19% Missing 2% - 1% - Variable Missing Full time students Yes Year in school 1st year undergrad 5th year or more undergrad graduate Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 18 Table 2 Percent of Mediation and Unstandardized Effects Direct Effects Indirect Effecta Total Effectb Mediation B (SE) B (SE) B (SE) % Stress Stress Stress Resilience Depression Resilience Depression Stress 1 .22 (.05) -.23 (.06) -.55 (.03) .13 (.03) .35 (.06) 37% Stress 2 .35 (.06) -.78 (.06) -.55 (.03) .43 (.04) .78 (.07) 55% Stress 3 .64 (.08) -1.21 (.07) -.55 (.03) .66 (.05) 1.30 (.08) 51% Note. Unstandardized coefficients are reported here. The corresponding standardized coefficients are found in Figure 1. All coefficients are adjusted for sex and age. Regression parameters for depression on age and gender are: .08 and .02 for the two age variables (>20 and <=30 vs. <= 20 and >30 vs. <=20, respectively), and -.02 for gender. Regression parameters for resilience on age and gender are: .04 and .13 for the two age variables, and .08 for gender. a At each level of stress, the indirect effect is the product of the effects of stress on resilience and resilience on depression (i.e., mediated through resilience). b At each level of stress, the total effect is the sum of the indirect effect (mediated through resilience) and the direct effect of stress on depression. Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression 19 Figure 1. Structural Equation Model e Academic S1 = .12 Depressive consequences S2 = .17 symptoms of stress (S1 - S3) S3 = .24 R2 = .41* S1 = -.13 S2 = -.39 .84 .89 .91 .77 -.52 dep e dep f R2 = .23 dep d Resilience** dep a e S3 = -.47 e e e e resil a resil b resil c resil d .80 .45 .94 .92 e e e e Figure 1. Model fit: WLSMV χ2(32) = 248.3, RMSEA = .057, CFI = .982 (N = 2,044). All shown coefficients are standardized and statistically significant. The variable “academic consequences of stress” was dummy coded with “no stress” as the referent (coded 0). S1: Stress that does not affect academic performance versus (coded 1), S2: Stress resulting in a lower grade on an assignment or project versus (coded 2), S3: Stress resulting in a lower or incomplete course grade versus (coded 3). Regressions on resilience and academic consequences of stress are adjusted for age and sex (these parameters are not shown here). * Standardized regression parameters for depression on age and gender are: .04 and .01 for the two age variables (>20 and <=30 vs. <= 20 and >30 vs. <=20, respectively), and -.01 for gender. ** Standardized regression parameters for resilience on age and gender are: .02 and .05 for the two age variables, and .04 for gender. Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression Figure 2. Frequency Distributions for Depression Items (Prior to Collapsing) 20 Running head: Stress, Resilience and Depression Figure 3. Frequency Distributions for Resilience Items Figure 3. These items were reverse coded in the statistical models. 21