Beef Cattle Farming

advertisement

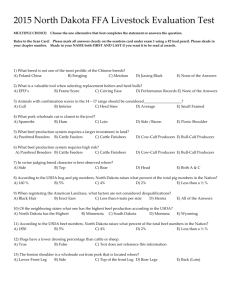

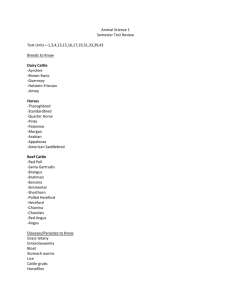

Beef Cattle Farming The importance of beef cattle to Canadian agriculture has increased steadily since the Second World War. There are about 86 500 beef cattle farms across the country; of those, more than 70% are cow-calf operations. Cattle Farming A cattle farm in Saskatchewan (courtesy Kate Johnson). Feed Lot in Saskatchewan. These cattle are being grain-fed for about three months in preparation for slaughter. They are housed in separate pens to segregate the cattle by size, ownership, and sex. Image: Agriculture Canada. Farming Types, Map Beef Cattle Farming Cattle (family Bovidae, genus Bos) were first brought to Canada by French settlers. In 1677 there were 3107 cattle in NEW FRANCE; in 1698, 10 209; by the mid-18th century, 50 013. Cattle were valuable as a food source (milk, cheese, butter, meat) and for their hides, used in LEATHERWORKING. Cattle farming spread across the country with settlement, and RANCHING became particularly important in the rangelands of western Canada. The importance of beef cattle to Canadian agriculture has increased steadily since the Second World War. There are about 86 500 beef cattle farms across the country; of those, more than 70% are cow-calf operations. The total livestock on Canadian farms is estimated at more than 15 million cattle and calves (including 1.6 million milk cows). Of these, 5.3 million are beef cows. Canada's beef cattle industry is the largest source of farm cash receipts. Farm cash receipts from the sale of cattle and calves total about $6.5 billion annually. The 1.3 billion kg of beef that the country produces annually contributes between $15 and $20 billion to its economy. About 3.5 million cattle are slaughtered annually across the country. Most of Canada's veal and young beef comes from a 3-phase system involving the cow-calf enterprise to produce weanling calves, the stocker or holding enterprise and the finishing (usually feedlot) operation. Two or three of these operations may be combined on a single farm or ranch. The triple combination, most common where breeding-herd size is small, is often a subsidiary enterprise of a mixed farming operation. Cow-Calf Enterprise The cow-calf enterprise involves maintaining a breeding herd to produce the heaviest weight of weaned calves possible. Cows are selected for their mothering ability, beef quality traits and other desired characteristics. Mating takes place in early summer and peak calving occurs in the following spring. On most farms, the entire cow-calf process takes place in open pastures, where the cattle graze and the calves nurse. Once the calves reach 225-275 kg (500-600 pounds), they are weaned from their mothers and are put on a forage-based diet. There are over 60 000 cow-calf farms across the country. Canada's beef-cow herd is estimated at approximately 5 million head. Breeding-herd size varies considerably, from a few cows on small mixed farms to several hundred in large range herds. The average Canadian beef-cow farm counts 61 head. Fortyeight percent of the beef-cow herd is now located on farms with more than 122 head. Large operations account for 13% of all beef cattle farms and are found in the 4 western provinces, where over two-thirds of Canada's breeding herds are located. However, about one-sixth of Canada's supply of veal and young beef comes from unneeded male and female calves of dairy herds, most of which are located in Ontario and Québec. The western emphasis on beef production probably stems from the fact that the cow-calf operation is usually based on a lowcost pasture resource, eg, sparsely vegetated areas, nonarable land (12 ha required per cow), or very intensively cultivated and irrigated pastures (0.5 ha per cow). Some of the largest operations are found on predominantly natural pastures requiring 8 ha or more per cow. In such areas, the winter feed supply may be purchased but most often comes from improved native meadows or intensively managed arable land. The female side of the breeding herd usually consists of cows and heifers of a single breed, or the female crosses of breeds that are likely to produce hybrid vigour in the various maternal characteristics such as milking and mothering ability. Performance-tested, purebred bulls from breeds noted for their post-weaning growth and carcass characteristics make up the male side of the herd (seeANIMAL BREEDING). Shorthorn The Shorthorn, originating in northeast England and southern Scotland, was the first beef breed to be established and the first to arrive in Canada (1832). Its superior growth and fattening propensity (over the nondescript cattle of the day) quickly made it popular. Reds, roans, whites, and red and whites are common colours in purebred herds, reds being the most popular. Mature cows weigh over 600 kg and bulls, 900 kg. A dual-purpose or milking Shorthorn strain has frequently been used in beef herds. A polled (hornless) mutant of the breed has become popular. Hereford Originating in the county of that name, the Hereford is a wellmuscled, hardy breed. Well known for its foraging abilities under difficult range conditions, the breed quickly established itself as western Canada's main commercial breed. Its attractive, predominantly white face, underline and other white markings on a red body became a trademark ("white face" or "baldy") among cattle producers. A polled strain was developed in Canada and the US from mutants. Aberdeen Angus The Aberdeen Angus, a smoothly finished black-coloured Scottish breed, has persistently found a place in beef production. Noted for its ease of calving and the easier delivery of Angussired calves, the breed also has other valuable characteristics in crosses (eg, early maturity, marbling quality of meat). A frequently occurring red mutant has now been developed as a separate strain. Other British breeds, including Galloway (polled and dun, black or white-belted black), Black Welsh, Lincoln Red (of Shorthorn origins), South Devon, Devon and Luing, have appeared over the years but have not been significant in Canadian beef production. Over the past 3 decades, the emphasis on growth and the hybrid vigour produced by crossing has resulted in considerable interest in continental breeds ("exotics"), especially since new quarantine regulations were adopted to facilitate importation. Charolais The Charolais, a very large white or creamy white breed of eastcentral France, was one of the earliest introduced. Its exceptional growth rate and muscling make it particularly valuable in crossing. Mature bulls average over 1000 kg and cows, 700 kg. A polled strain is being developed. Limousin A yellow-brown horned breed about the size of the Hereford, the Limousin was the second continental breed to arrive in Canada and is valued for its excellent ratio of lean to fat and bone, a characteristic persisting in crosses. Simmental The Simmental, one of the most popular European breeds, is a dual-purpose (predominantly dairy) breed. Of Swiss origin, this large red and white breed is known under various names throughout Europe. For beef production, the valuable characteristics are rapid growth and milk production. Other continental breeds popular in cross-breeding are MaineAnjou, a large red and white breed from northwest France; Blonde d'Aquitaine, from southern France; 3 white breeds from Italy, ie, Chianina, equal in growth rate and mature size to the Charolais, and its smaller sister breeds, Romagnola and Marchigiana; Gelbvieh, a large, red German breed; and Salers, a smaller red breed of central France. Summer grazing is usually controlled by a good distribution of watering facilities and trace-mineralized salt licks, pasture rotation, or movable electric fences. Calves, "identified" at birth, run with cows. If not naturally polled, they are usually dehorned and vaccinated against common diseases (eg, blackleg) early in the pasture season. Male calves are generally castrated. If range is limited or extra gain is economically warranted, calves may have access to grain. Breeding takes place in summer, preferably during a 6-week to 2-month period when cows are exposed to fertility-tested bulls (approximately one bull to 30 cows). Yearling heifers (approximately 15 months old), if well grown (300 kg), are bred to sires known to produce easily delivered calves. High conception rates are extremely important but seldom exceed 8590%. Calves are weaned from early October to mid-November, usually just before winter feeding. At 6 months, calves from British breeds and their crosses usually average 200 kg for males and 185 kg for females. Earlier-born calves or crosses with "exotics" may be 50-100 kg heavier. Male calves and those females not needed for breeding are transferred to stocker operations, as are cows that failed to become pregnant or produced poorer calves. Wintering requires feeding in most areas, although pasture or cash crop residues may be used, weather permitting. In some areas, eg, the CHINOOK belt, winter grazing of mature herds on specially reserved pastures is normal. Feed is supplied only under severe weather conditions and before calving. The herd is usually broken into 3 or 4 groups so that replacement heifer calves, pregnant yearling heifers and 2-year-olds expecting their first calves can be fed to facilitate growth. In large herds, bulls are usually fed and managed separately. In the smaller herds, they may be allowed to run with the mature and pregnant cows. Winter feed is usually home-grown hay or silage from GRASSES, legumes or CEREAL CROPS. Grain and protein concentrates may augment poor-quality feeds; mineral mixtures and vitamin A supplements are the main purchased feeds. The average cow will consume 2% of its body weight in dry feed (eg, hay) per day; hence, wintering a mature cow normally requires 2 t of feed. Stocker Operation The stocker operation is normally attached to the cow-calf or the finishing enterprises, being essentially a period of growth between weaning and the finishing phase for slaughter (6-12 months). It is roughage- and pasture-based, aimed at getting as much efficient youthful growth of skeleton and muscle as possible. As a single enterprise, it is highly speculative and is usually a "grasser" operation for individuals with ample pasture but no winter feed. These farmers buy wintered steer and heifer calves in spring, and then resell them in late summer or fall to feedlot operators. Finishing Operation Finishing, the final step in preparing animals for slaughter, aims to increase body weight and value. While some cow-calf operators may carry out this enterprise after a stocker phase for their own calves, most finishing is now done in specially designed units, holding several hundred or thousands of animals. Some farmers, eg, a few in Ontario, traditionally used the feedlot to enhance the value of their home-grown crops and to provide a winter occupation. Larger units may be equipped with feed- preparation mills and most use mixing and unloading trucks to distribute the feed in long troughs. Profits arise from 2 sources: price margin, ie, the difference between the buying and selling price (the original 300 kg weight of a steer purchased for $1.80/kg and sold for $2.00/kg has produced a profit of $60.00 through the $0.20/kg price margin); and feed margin, ie, the difference between the cost of a kilogram of gain and the selling price of that gain. Thus, if it cost $1.90/kg to put on 200 kg in the feedlot and the 500 kg finished steer sold for $2.00/kg, the operator has had a gain of $20.00 through a positive $0.10/kg feed margin. Astute and fortunate buying and selling may govern pricemargin profits, but feed margin is dependent on cattle that are efficient users of feed and on low-cost rations. Calves 6-8 months old are the most efficient converters of feed (6-8 units of feed per unit gain) but are the slowest gainers (1.0-1.1 kg/day) and require the longest feeding period. Yearlings are less efficient (8-9 units of feed per unit gain) but gain faster (1.1-1.3 kg/day) and usually require 140 days in the feedlot. Heifers usually gain slightly more slowly in the feedlot and finish at lighter weights. The key in finishing is high-energy feed (eg, grains of BARLEY, CORN and, to some extent, WHEAT and OATS) fed with bulky roughages (eg, corn silage, hay, straws). In local areas, some refuse or byproducts (eg, distillers' slops, brewers' grains, BEET pulp and molasses, milling and canning crop residues) may form the basis of less efficient but profitable feeds. Lower-quality feeds are usually used in the first part of the finishing period. As the animal increases in weight, each new unit of gain requires more or better feed, and higher-energy feed is needed to produce economical gains. In most parts of Canada, finishing cattle on grass alone is not economical, as top grades can seldom be reached because of the yellow colour of the fat in most breeds or the lack of sufficient fat covering in yearling or younger cattle. It is very effective and more economical if the last 60 days are spent in dry lot. In spite of the vagaries of price fluctuations and increasing costs, beef farming has persisted, as beef is the meat preferred by most consumers. Over the long term, it has produced reasonable returns; however, since the annual operating costs are high, because of the large capital involved in land and cattle, many operators cannot withstand years of low returns and high interest rates.