Connected Speech Processes

advertisement

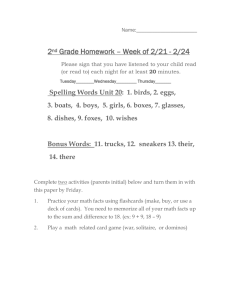

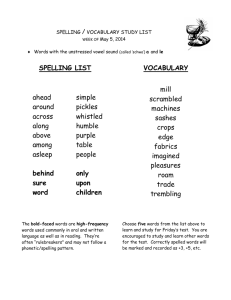

Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 Understanding English Variation Week 4 – Connected speech processes and the principles of English spelling 1 Connected Speech Processes What are connected speech processes? Connected speech processes are changes in the pronunciation of words when they are in a sentence. So far, we have only really considered the sounds of words in isolation but today we will consider what happens when words are joined together to make sentences. Each type of change has a different name. We will consider assimilation, elision and r-sandhi. 1.1 Assimilation Sounds that belong to one word can cause changes in sounds belonging to other words. When a word’s pronunciation is affected by sounds in a neighbouring word, we call this process assimilation. We find that sounds in the affected word become more like sounds in the neighbouring word. The two sounds can become more alike in terms of voice, place or manner. Assimilation occurs when speech is rapid and casual. Changes in sound that occur in rapid speech are said to be due to gradation. Direction of change If a phoneme is affected by one than comes later in the sentence, the assimilation is termed regressive. If a phoneme is affected by one that came earlier in the utterance, the assimilation is termed progressive. Phoneme 1 Phoneme 2 progressive regressive Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 1.1.1 Assimilation of voice Across word boundaries In English, only regressive assimilation is found across word boundaries and then only when a voiced word final consonant is followed by a voiceless word initial consonant. Example: big cat > It is never the case that a word final voiceless consonant becomes voiced because of a word initial voiced consonant (although this does happen in many languages). Across morpheme boundaries When a noun is pluralised by adding a n<s> suffix the pronunciation of the <s> depends on the voicing of the final consonant of that noun. If the final consonant is voiced, the suffix will be pronounced as [z], if the final consonant is voiceless, the suffix will be pronounced as [s]. As an earlier consonant affects a later one, this is an example of progressive assimilation. This process in fixed in English as there are hardly any exceptions. Examples: Cats Dogs voiceless final consonant and suffix voiced final consonant and suffix The same is true when an <s> is added to a noun to make a possessive suffix or to a verb to make the third person singular suffix. Examples: Possessive Jack’s John’s Third person singular She jumps She runs voiceless final consonant and suffix voiced final consonant and suffix voiceless final consonant and suffix voiced final consonant and suffix Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 1.1.2 Assimilation of Place Across word boundaries In English, assimilation of place only occurs regressively across word boundaries and only with the alveolar consonants (including clusters of alveloars). Examples: That person That thing Good night : : final alveolar changes to bilabial final alveolar changes to dental : final alveolar changes to velar The alveolar fricatives and change to and respectively when followed by or Examples: This shoe > (regressive) Those years > (regressive) Within words Within codas, if a nasal comes before a plosive or a fricative, its place of articulation is determined by that of the other consonant. This process is fixed in English as there are very few exceptions. Examples: Bump bilabial nasal and plosive Bank velar nasal and plosive Hunt alveolar nasal and plosive Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 1.1.3 Assimilation of manner Assimilation of manner is only found in very fast casual speech. In general speakers change sounds to sounds that are ‘easier’, those that obstruct the airflow less and therefore require less energy. Examples: Good night > n a final plosive becomes a nasal (regressive) That side > a final plosive becomes a fricative (regressive) Read these : : > : : an initial fricative becomes a plosive (progressive), this only happens when a word final nasal or plosive is followed by a word initial 1.1.4 Coalescence Coalescence is a special type of assimilation process. In coalescence, the process of assimilation is bi-directional and two segments combine to produce one. In English this often happens when an alveolar plosive is followed by a palatal approximant (j) and they combine to form a palato-alveolar affricate. Example: Did you : > : Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 1.2 Elision Elision is the loss of a phoneme. In technical language we say that the phoneme is deleted or is realised as zero. Elision occurs more in fast casual speech, thus elision is a process of gradation. There are many examples of elision in English, a few are given below. Example: Loss of a weak vowel after voiceless plosives (p, t, k) Potato > (schwa is lost, p is aspirated) Avoidance of complex clusters George the sixths throne Loss of final v in ‘of’ before consonants Lots of them > > 1.3 r sandhi Sandhi is a process where a sound is modified when words are joined together Some linguists distinguish two types of r sandhi,, linking and intrusive r. 1.3.1 Linking r You will remember that for speakers of non-rhotic accents r is not pronounced after vowels. So the pronunciations of ‘car’ is : and of ‘more’ is : However, in these accents, when words that are spelled ending with an <r> or an <re> come before a word beginning with a vowel, the r is usually pronounced. This is linking r. In rhotic accents the r is also pronounced when the words are in isolation so cannot be termed linking. Examples: Far away More ice : : > > : 1.3.2 Intrusive r Intrusive r also involves the pronunciation of an r sound, but this time there is no justification from the spelling as the word’s spelling does not end in <r> or <re>. Again this relates to non-rhotic accents; rhotic accents do not have intrusive r. The idea of it > Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 2 The Principles of English Spelling Differences of accent can complicated the process of learning to spell (particularly use of rhoticity and vowels). What is clear is that English is not entirely regular. Although there are lots of rules, there are many words which do not follow them. The following sections discuss some of the sources of irregularity. 2.1 Old English The problems began when Christian missionaries began to use their 23 letter alphabet to represent the 35 phonemes of Old English. This meant that some letters had to be used for more than one sound, for example <c> represented /k/ and /s/ introducing complications and irregularities. 2.2 Middle English After the Norman Conquest French scribes brought many French spelling conventions to written English <qu> replaced Old English <cw> e.g.‘quick’ <gh> replaced <h> e.g. ‘night’ <u> looked similar to written <v>, <m> and <n> so they replaced it with <o> in cases where it followed these letters ‘love’, ‘come’, ‘son’ When Caxton brought his printing press to London, spelling gradually became stabilised and the London dialect was used as standard. Some other continental conventions were introduced however, and sometimes printers would miss letters out of words so they would fit on the line. 2.3 Early Modern English Although printing had stabilised spelling, pronunciation was still changing. During the Great Vowel Shift the English long vowels underwent huge changes. However, because printing had already established spelling conventions, the spelling of many words now reflects a much older pronunciation. For example, in Chaucer’s day, the vowel in ‘name’ was /:/ but this changed to // during the shift. The spelling still reflects the older pronunciation. The shift affected all the English long vowels. Silent letters are a similar case. Letters such as <k> in ‘knee’ and <e> in ‘time’ were pronounced at the time spelling was standardised but were lost from pronunciation later on. Rachael-Anne Knight, 2003, University of Surrey - Roehampton Understanding English Variation, Week 4 2.3.1 Etymology In the 16th century many scholars decided that spelling should be altered to reflect the roots of words. So, for example, a <b> was added to ‘debt’ to reflect its origins in the Latin word ‘debitum’. 2.3.2 Borrowings In the 16th and 17th centuries, many non-English words were introduced into the language from French, Latin, Greek, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese. Often the spelling was left unchanged from the foreign spelling. The problem continues today as we still borrow extensively (think about ‘quesadillas’). 2.4 Rules and regularity Despite all this irregularity, there are many regular aspects to English spelling. To give one example, consider the English vowel sounds and spellings. In English the letters <a> <e> <i> and <u> all have to represent two vowels, one short and one long (or diphthongal). <a> <e> <i> <o> <u> as in ‘cape’ : as in ‘meter’ as in ‘line’ as in ‘go’ : as in ‘lucid’ as in ‘mat’ as in ‘met’ as in ‘bit’ as in ‘pot’ as in ‘cut’ There is, however, regularity to some extent as the length of the vowel is usually indicated by either: Consonant doubling indicates a short preceding vowel cp. ‘coma’ and ‘comma’ or A final <e> after a consonant marks the previous vowel as long cp. ‘win’ and ‘wine’