Weak Syntax

advertisement

Grodzinsky, Y. and K. Amunds (eds.) Broca's Region. Oxford University Press. 2006.

Weak Syntax*

Sergey Avrutin

Utrecht University

Abstract

The goal of this article is to outline a model that accounts for a variety of findings in Broca's

aphasics and connects these observations with the data from unimpaired language. The

model is based on the interaction of the narrow syntax, the information structure (also known

as "linguistic discourse", "conceptual-intentional interface" or "information structure") and

the context.

It is argued that the damage to the Broca's region does not result in the

impairment of syntactic capacity, in the sense that knowledge of certain principles of the

narrow syntax is lost. Nor is it the case that some parts of the linguistic structure (such as a

trace, or, in current terms, a copy of a constituent) are missing. Rather, in the proposed

model the syntactic apparatus of Broca's aphasics is argued to be significantly weakened,

which results in a reliance on alternative, non-syntactic means for encoding information

(which are also available for non-impaired speakers.)

1. Introduction

Why should linguists be interested in the study of Broca's region? There are, in my view,

several reasons why such investigation is mutually beneficial for linguists and aphasiologists

alike. Not only does linguistic theory provide a tool for the proper characterization of Broca's

area's function, but studies of this area, especially research with aphasic speakers, may

contribute to a proper formulation of a linguistic theory. Indeed, the computational theory of

mind, an approach widely accepted in today's cognitive science, views the relationship

between language and the brain as analogous to the relationship between software and

1

hardware. For any computer to function properly -- and the human brain is, in some sense, a

natural biological computer -- there must be a well-functioning hardware capable of running

particular (domain-specific) software. Theoretical linguistics can thus be characterized as a

study of the natural, language-related software, a study that aims at giving a precise

characterization of the rules the language areas of the brain should be able to support.

Aphasiology, on the other hand, can contribute to the proper formulation of a linguistic

theory in at least the following way. Assume two competing linguistic theories, one of which

lumps two linguistic observations together (e.g. two different types of linguistic

constructions,) while the other suggests that the observed facts are to be explained by

different principles. The two theories would make different predictions about the linguistic

performance of brain damaged patients: the first one would predict a similar performance on

the two constructions (both good or bad), while the other would predict a possible

differentiation1.

Another reason involves the division of labor between various components of

language system. Correct comprehension (and production) involves interplay of various

domains, such as morphology, syntax and discourse. To properly characterize the function of

Broca's region, researchers need to have a clear picture of what kind of linguistic processes

are involved in interpreting a particular structure under investigation.

In this sense,

developments in linguistic theory may have significant consequences for our understanding

of the function of Broca's region. A rather characteristic example in this sense is the pattern

of errors observed in experiments with aphasic patients in their off-line comprehension of

pronominals (e.g., Grodzinsky et al 1993) or in aphasics' errors in on-line studies (e.g. Love

et al 1998). While investigating somewhat different constructions, both of these studies

observed an abnormal pattern of comprehension or activation in these patients.

The

explanations proposed in these studies, however, were based mostly on the theory of

2

anaphora available at that time, that is, Chomsky's Binding Theory (Chomsky 1986).

Specific conclusions about the function of Broca's region were drawn on the basis of that

theory, but it appears clear now that the theory was inadequate and conceptually problematic

(for review see Reuland 2003). More specifically, it has been argued that syntax (or the

"narrow syntax", in current terms) is unrelated to the constraints on pronominals of the type

investigated in the above-mentioned studies.

Thus, the pattern of errors observed

experimentally calls for a non-syntactic explanation, and, consequently, the function of

Broca's region (at least in this regard) needs to be re-considered as including operations

beyond narrow syntax.

The next problem follows immediately. If Broca's aphasics demonstrate some kind of

comprehension deficiency, such as interpretation of passive constructions or object relative

clauses, is it reasonable to attribute this deficit to the disruption of their syntactic machinery?

This question arises because the function of Broca's region in this case becomes rather

undifferentiated: it would have to support processes that, according to theoretical linguistics,

belong to different parts of language architecture.

All else being equal, a characterization of the function of Broca's region should be

able to account for a variety of dysfunctions in a more or less unified way. It seems to me

that researchers often provide a detailed linguistic characterization of some particular

comprehension errors in aphasia without attempting to connect their explanation with the

well-known difficulties in speech production in these patients.

The two modalities --

production and comprehension -- are treated as if they had nothing to do with each other and

as if it were a pure coincidence that one and the same patient (with a particular brain damage

in Broca's region) has an effortful, telegraphic speech, with multiple omissions (or

substitutions) while, in comprehension he or she demonstrates a chance performance on

passive constructions.

3

Finally, a proper formulation of a linguistic theory can explain to what extent

"agrammatism" often attributed to Broca's aphasics represents a case of producing truly

"ungrammatical" utterances. In other words, there is a distinction between an unacceptable

utterance and an ungrammatical one. An utterance can be unacceptable because of variety of

reasons, only some of which are syntactic in nature. As will be demonstrated shortly, what

we often judge as ungrammatical represents, in fact, a case where certain (required)

contextual conditions are satisfied. The sentence is, indeed, unacceptable in a particular case,

but it has nothing to do with grammar: it is grammatically well-formed. This is perhaps a

question of terminology, but if we take the notion of "ungrammatical" to mean something

that violates the rules/principles of the narrow syntax (as I believe researchers often do), we

cannot ignore the fact that some "ungrammatical" expressions typical for Broca's aphasics are

often observed in unimpaired populations as well. To give a brief example (a more detailed

discussion follows below) frequent omission of subjects in the speech of English-speaking

aphasics is a typical characteristic of the diary style register in unimpaired English (for

discussion and examples see Haegeman 1990). Non-finite main clauses, frequently observed

in the speech of Dutch and German Broca's aphasics (e.g. Dutch hij lachen! 'he to-laugh!') are

fully productive (and fully acceptable) in some special registers in these languages (e.g. Kolk

and Heeschen 1992, Blom 2003, Tesak and Ditman 1991, Avrutin 2004, among others.)

Indeed, the range of contextual circumstances when such utterances are used by normal and

aphasic speakers differ significantly, but the point is that by itself such omissions do not go

beyond what is allowed, under certain conditions, in unimpaired language. If so, a proper

formulation of an aphasic syndrome, and hence a better understanding of Broca's area's

functions, has to be provided in such terms that it could explain why allegedly ungrammatical

utterances are allowed in unimpaired speech as well, provided the contextual conditions are

satisfied.

4

2. The Model

2.1. What does the model seek to account for?

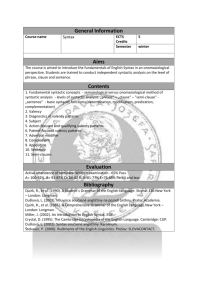

As a first step, the proposed model seeks to provide an explanation for the following

observations:

a. Omission of some functional categories, such as determiners and tense, is allowed in

unimpaired speech in many languages that are traditionally assumed to require these

elements. Importantly, however, such omissions are allowed only when specific contextual

conditions are satisfied. Thus, the model needs to show why such omissions are in principle

possible, and why they are restricted to special (context-related) registers.

b. Optional omission of functional categories is a characteristic feature of Broca's aphasics'

speech in languages such as Dutch, German, English, and Swedish. The model seeks to

provide an explanation for why these elements are omitted in aphasic speech and why such

omission is optional (i.e. the same patient sometimes omits and sometimes produces a

determiner.) In addition, the model needs to explain what role the context plays in the

omission pattern in aphasic speech, given that such omissions are allowed in special registers

(see above.)

c. Aphasic speakers demonstrate significantly more errors with tense than with agreement.

The model needs to explain why there is such difference.

d. As discussed below, there is a correlation between omission of determiners and tense in a

given utterance of an aphasic speaker. This correlation needs to be accounted for within the

proposed model.

e. The above observations have to do with speech production. Well-known phenomena of

comprehension (such as poor comprehension of passive constructions and object relative

clauses) need to be explained within the same model.

5

f. The proposed model seeks to connect the above mentioned linguistic observations with

more low-level facts about brain damage, specifically with lower than normal brain

activation. In other words, the goal is to show how diminished available brain resources

results in what may appear to be a structural deficit.

g. As an illustration for the last point, the model seeks to account for recent results on

comprehension of pronouns by Dutch Broca's aphasics. As discussed in section 3, these

patients demonstrate a significantly worse performance precisely in those cases where the

processing economy hierarchy is at stake.

It has to be acknowledged, of course, that at this point it is perhaps impossible to

come up with a truly unifying theory that would connect all experimental and theoretical dots

in a scientifically harmonious way. Clearly, this is not my intention in this article.

Nevertheless, I will attempt to outline a new approach to the investigation of aphasics'

linguistic errors. This model represents a further development of ideas outlined in Avrutin

(1999); its application to the child data is provided in Avrutin (2004).

2.2. Special registers in unimpaired speech.

As mentioned above, omission of functional categories is allowed in unimpaired language,

although only in some restricted contexts. Consider, for example, (1). Taken out of context,

this sentence is unacceptable in English:

1)

*John dance.

However, as noticed, for example by Akmaijan 1984, Tesak and Dittmann 1991, Schütze

1997, among others2, this construction becomes acceptable in the so-called Mad Magazine

register:

2)

John dance???!!! Never!

6

Similar examples exist in Russian and Dutch. A tenseless clause (3) is unacceptable if

produced "out of the blue", but it becomes fully "normal" when it follows, in a given

discourse, a completed event (as in (4)):

3)

*Deti prygat' ot radosti.

[Russian]

Children to-jump[INF] of joy

'children started jumping out of joy"

4)

Ded Moroz prinjos podarki. Deti prygat' ot radosti!

Santa Clause has brought gifts. Children to-jump[INF] of joy!

5)

Maria vertelde Peter een mop. Hij lachen.

Mary told

Peter a

[Dutch]

joke he laugh-inf

Omission of determiners in a language that normally requires them is also possible in a

specific context, as illustrated by the following Dutch examples (from Baauw et al 2002, see

also Tesak and Dittmann 1991.)

6)a.

Q:

Wie heeft jou gisteren gebeld?

‘Who called you yesterday?’

A:

Oh, meisje van school

Oh, girl

b.

from school

Leuk huisje heb je.

nice house have you

Such expressions are fully acceptable and productive, both in Russian and Dutch; however,

they do require specific contextual conditions. For example, Russian non-finite clauses are

possible only if they follow a completed event (see example (4) above.) Dutch determinerless

NPs are acceptable only in specific contexts where there is a sufficient presupposition with

regard to the referent of the NP. Thus, what these examples suggest is that the function of a

functional category can be sometimes taken over by the context. When such conditions are

7

not satisfied, functional elements must be provided in order to make an utterance

interpretable. In the next section I outline a model that will allow us to capture the interaction

between the narrow syntax, information structure and context. I begin with how the proposed

model explains the omission pattern in special registers in unimpaired speech and what role

the context plays in this case. I will extend the application of the model to aphasia in section

2.4.

2.3. From the narrow syntax to information structure and beyond.

Following the basic tenets of the Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1995), I assume that narrow

syntax is a computational system that is isolated and encapsulated with respect to meaning,

that is that such system conducts symbolic operations on lexical items putting them together

in some specific order that is allowed in a given language. The output of this system must be

eventually interpretable. The meaning of lexical items by themselves is clearly not always

sufficient; for example, the interpretation of a pronominal element depends on the

information in the linguistic discourse. Thus, the output of the narrow syntax is submitted to

what Chomsky calls Conceptual-Intentional interface (C-I). In my view, this is precisely the

same level as linguistic discourse, or information structure (as in Vallduví 1992), as it is

precisely here that the information about topic, focus, specificity as well as pronominal

anaphora is encoded.

As will be seen shortly, I distinguish between the notions of linguistic discourse and

the context. The linguistic discourse for me is a level of representation responsible for

resolving (at least some) anaphoric dependencies, identifying topic and focus, determining an

appropriate antecedent for a logophoric element,3 as well as performing other operations

usually referred to as "discourse operations." This system is constructed dynamically in the

course of a given conversation and operates by rules that go beyond a sentence level. What I

mean by context, on the other hand, is a non-linguistic system of thought that can be modified

8

by different means, including, but not limited to, linguistic ones. Thus, the way the term

"discourse" is sometimes used in the literature is, in my view, somewhat confusing as it

encompasses both purely linguistic operations ("linguistic discourse" in my terminology) and

the context. To avoid confusion, I will use the terms "information structure" and "context"

throughout this article.

The Information Structure is part of the computational system involved in language.

Like the narrow syntax that operates on syntactic symbols according to its specific principles,

the Information Structure operates on its own symbols and in accordance with its own rules.

Depending on a particular theory, these symbols can be represented as a discourse

representation structure (DRS, Kamp and Reyle 1993), or a file card (Heim 1982). The point

is that there is, at this level, a basic unit, a chunk of information, that must be made

completely interpretable. This, in fact, may be a non-linguistic requirement: After all, any

communication system, and language is such a system, should be designed in such a way that

it transmits interpretable chunks of information.

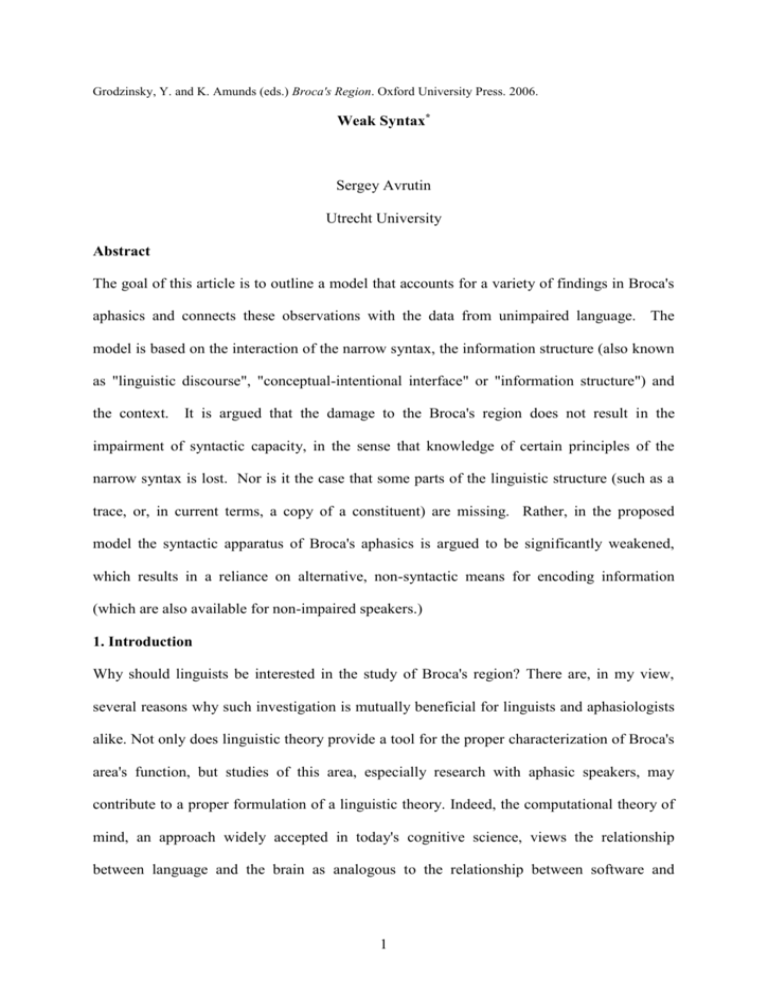

In Avrutin 2004, I discuss some constraints (and a possible reason for their existence)

that ensure the well formedness of the information structure. The central idea is that the units

of this system consist of two parts: a frame and a heading. They are introduced, respectively,

by functional and lexical projections from the narrow syntax. The units of information

structure must contain both parts in order to be fully interpretable. A frame ensures that

information units are separated from each other, and a heading provides the information

necessary for interpretation. The diagram below illustrates relationship between narrow

syntax, information structure and other, non-linguistic cognitive faculties, such as context4.

The frame of the unit is supplied by determiner 'a', and the heading is supplied by noun 'dog'.

This entity represents what we may call an Individual Unit of information (or an individual

file card, adapting Heim's 1982 terminology.)

9

PLEASE INSERT FIG. 1 HERE

Similarly, a TP in (7) contains a functional element T and its lexical complement VP.

7)

TP

3

T

VP

+fin

run

As a result of the translation from the narrow syntax into the information structure, we obtain

an event unit of information (or an event file card) represented in Fig. 2 (T supplies the event

heading, and V supplies the heading.)

PLEASE INSERT FIG. 2 HERE

Let us look again at the special register exemplified in (1) - (6). Characteristic of these

examples is that they represent a case where functional categories are missing. Thus, at the

level of information structure, such expressions are unable to introduce frames. At the same

time, as mentioned above, they are fully acceptable, provided certain contextual conditions

are satisfied. That means that certain contextual conditions can take over the function of

functional categories, specifically to introduce a frame. In principle, this should not be

surprising, as the information structure is an intermediate level between the narrow syntax

and our general cognitive capacity, which is involved in constructing the context

representation. Thus, it is reasonable that this interface level may be subject to impact from

either side.

This would make information structure qualitatively different from narrow

syntax, which is fully isolated, autonomous, and encapsulated. As such external conditions

10

cannot influence the well-formedness of a structure in narrow syntax; however, such

influence is possible in information structure. Consider again example (6a). The response is a

determinerless expression, so the narrow syntax does not supply the material necessary for

introducing an individual frame. However, the specific contextual circumstances -- the fact

that the text is a question-answer pair with strong presupposition by the speaker -- allows the

listener to "rescue" the incomplete information unit by alternative means, namely by

inference about speaker's presupposition.

Notice that figures 1 and 2 above represent the process of speech comprehension: the

information units are constructed by the listener on the basis of narrow syntax (e.g. on the

basis of the parser's output.) In the case of special registers, the model should look slightly

different. Indeed, in this case it is more appropriate to describe the process of encoding of a

message by the speaker. Adapting Levelt's (1989) model of speech production, we can

represent the information unit as a message that needs to be encoded by the speaker

(normally through morphosyntax) in order to be transmitted to the listener. I suggest that in

case of special registers some information is presupposed on the basis of a given context, and

therefore does not need to be encoded by linguistic means. In terms of information transfer,

we can say that some information is transmitted through context.

PLEASE INSERT FIG. 3 HERE

A tenseless main clause is similar. As mentioned above, the necessary condition in Russian

seems to be that there is a specific temporal point introduced in the previous linguistic

discourse, to which the new event can be anchored (in terms of Enç 1991).

If the speaker

has provided such a point in the linguistic discourse, it will be part of the context. The

encoding of the temporal information by morphosyntax thus becomes unnecessary, as the

11

listener will be able to infer the temporal information about the tenseless clause, and to

introduce the event frame by non-syntactic means:

PLEASE INSERT FIG. 4 HERE

Crucially, if the discourse condition is not satisfied, a tenseless main clause is unacceptable

because the event information unit has no frame: it has not been provided either by the

narrow syntax or by the context.

Notice that the proposed model makes clear what the context can and cannot do.

Specifically, when a certain element is needed because of the requirements of the narrow

syntax, it cannot be omitted (that is, supplied by the context), because the narrow syntax is an

independent, modular system. Reliance on context is possible only in those cases where the

requirements of the information structure are at stake. A clear example of this distinction is

the respective roles of agreement and tense. As a morphosyntactic characteristic, agreement

must be present because of the narrow syntax requirements. Tense, on the other hand, is

required to make a connection (anchoring) of an utterance to the linguistic discourse (e.g. Enç

1991.) Thus, the model predicts that there will be no register that would allow for omission

of agreement. Indeed, this seems to be the case: while many languages allow a non-syntactic

encoding of the event frame (e.g. non-tensed main clauses), they do not allow omission of

agreement (e.g. no register in Russian would allow a sentence like *deti prygnul

'children[PL] jumped[SING]'.) This feature of the model is important because it makes

further predictions about errors in aphasic speech, discussed below. Briefly, it predicts that

problems with tense should be observed significantly more often than problems with

agreement in the speech of these patients.

12

A question that arises at this point is why "special" conditions would be necessary for

"special registers." In other words, if the possibility of encoding an event or an individual

frame by non-syntactic means is in principle available in natural languages, why don't

speakers always omit functional categories and rely on (often quite reliable) context in order

to build the information units? I would like to propose that the answer is related to economy

considerations. I hypothesize that in normal adult speakers, narrow syntax is the cheapest,

most economical way of encoding individual and event frames and that this is the most

economical way of building information structure5. This is in line with the theory formulated

in Reuland (2001) for unimpaired language. He argues that operations that take place at

different levels (syntax, semantics, discourse) form an economy hierarchy, the syntactic ones

being the cheapest and the discourse ones being the most expensive. Thus, the use of narrow

syntax in unimpaired language for encoding messages follows from its position in the

hierarchy.

2.4. Economy in Broca's aphasia.

The cheapest, most economical option in unimpaired language does not necessarily

enjoy the same status in the language of brain-damaged patients. If Broca's region is involved

with syntactic computations, it is only natural that damage to this area would make these

operations more resource consuming. The economy hierarchy will then be different: what

used to be the easiest way of building information structure, or encoding messages, will now

become more expensive than (or at least equally expensive as) other options in principle

available to the language system. The straightforward reflection of such change in the

economy hierarchy will be noticeable precisely in those cases where, in unimpaired language,

alternative options are avoided because of their relatively higher cost.

13

What I propose therefore is a possible way of what a theory of complexity may look

like if it is to explain certain omissions in production and some specific errors in

comprehension. The main idea is that the resources necessary for conducting syntactic

operations are diminished in Broca's aphasia, with consequences reflected both in the

production pattern and in comprehension errors of these speakers6.

2.4.1. Production

In production, the use of narrow syntax ("the syntactic channel") becomes less

efficient since it is no longer the most economical option available. Rather, an alternative

option is now used, specifically, reliance on the context. Importantly, this option is also

available for unimpaired speakers in special registers. In other words, damage to Broca's

region does not create a new information - processing system. Depending on the degree of

severity of damage, or perhaps on other factors still to be investigated, the two means -syntactic and non-syntactic -- may become comparable with each other in the amount of

information they can encode and transmit. We would then expect to see occasional use of the

syntactic channel, and occasional use of the non-syntactic one. The result is the well-known

phenomenon of variability in aphasic speech.

The proposed model also makes an interesting prediction about the correlation

between omission of determiners and tense. Because such omissions represent the use of nonsyntactic means of transmitting information, the prediction is that once this alternative is

selected by Broca's aphasics, it is likely to be selected for both functional categories. This

prediction is borne out. Baauw et al (2002) presented evidence that there is a correlation

between omissions of these two functional elements. For the utterances of a group of Dutch

speaking Broca's aphasics, it was shown that the more likely a sentence was to contain tense,

the more likely it was that a determiner would also be produced. And the other way round:

tenseless clauses are more likely to contain determinerless NPs. The authors argue that this

14

correlation is due to the optional reliance on non-syntactic means for introducing information

units: if a non-syntactic root is chosen (as the easiest in the sense discussed above), it is more

likely to fulfill all functions with regard to encoding a message, both for individual and event

information units7.

As discussed above, the ability of the context to compensate for what has not been

encoded morphosyntactically is limited. If a certain element of the structure is required

because of the requirements of the narrow syntax (a modular, independent computational

system), this element cannot be omitted. Again, for example, there is no register such that

allows mismatch in agreement. The prediction about Broca's aphasics is then that these

patients would make significantly fewer errors with agreement than with tense, because there

is no alternative way to encode agreement rather than by means of morphosyntax. Indeed, as

many authors have argued, there is a difference in aphasics' performance with respect to these

two elements. Friedmann 1999, Benedet et al. 1998, Kolk 2000, and Wenzlaff and Clahsen

(in press), among others, show that Hebrew, Dutch and German speaking Broca's aphasics

are more impaired with tense than with agreement. Given that in many cases these patients

produce a non-finite verb, the results support the proposed model.

To continue this line of argument about what the context can and cannot do, it is

important to remember that the speech of Broca's aphasics is not overall impaired. It has

been demonstrated that these patients are sensitive to some subtle syntactic constraints.

Bastiaanse and Zonneveld (1998), for example, show that the use of non-finite forms in

aphasics is restricted to the main clause (the authors’ claim being that agrammatics have

problems with verb movement that takes place in Dutch only in the main clause; see

however, Lonzi and Luzzatti 1993). When asked to complete a sentence with a missing verb,

agrammatics produced finite forms only 49% of the time; in embedded clauses, however,

their performance increased to 86%. Avrutin (1999) suggests that these findings demonstrate

15

patients' sensitivity to what Gueron and Hoekstra (1995) label "the tense chain," the

requirement on the coindexation of Comp and T. Thus, they preserve the subtle syntactic

knowledge that in the presence of overt Comp, only finite T can participate in the tense chain.

Further support for this view comes from the observation that these speakers always produce

tensed auxiliary verbs and modals (even in the main clause), the elements that head TP and

therefore occur in the tense chain (e.g. Bastiaanse and Jonkers 1998, Kolk 1998, De Roo

1999)8.

Broca's aphasics also demonstrate subtle syntactic knowledge of the relationship

between verb movement and finiteness. Kolk and Heeschen (1992) show that if a non-finite

verb is produced by a Dutch or German (V2 languages) aphasic speaker, this verb, in the vast

majority of cases, is in the clause final position; a finite verb is always correctly placed in the

second position. Lonzi and Luzzatti (1993) report similar results for Italian Broca's aphasics.

The authors observe that when the verb is nonfinite, it either precedes or follows the adverb

(both positions are correct in Italian), but when the verb is finite, the adverb always follows

it.

As for comprehension, which I will discuss shortly, Broca’s aphasics do not differ

from normal speakers in their sensitivity to a verb’s representational complexity. Thus, as

Shapiro et al (1987) demonstrate, it takes longer for normal speakers to process verbs that

have more possible argument structures (e.g. alternating datives such as ‘send’ take more

resources than a transitive verb such as ‘fix’). Following up on this study, Shapiro and

Levine (1990) showed that Broca’s aphasics exhibit a similar pattern of performance: while

their reaction, overall, is significantly slower than normal, the same distinction between verbs

with regard to the argument structure complexity can be detected in these patients.

Interestingly, the above findings represent precisely those cases where the context

cannot serve as an alternative. Verb movement, for example, is triggered by the principles of

16

narrow syntax and has no direct consequences for building of information structure.

Moreover, there is no register in unimpaired Dutch or German that would allow a non-finite

verb in the second position.

These observations further support the claim that the

"agrammatic" performance exhibited by Broca's aphasics does not constitute impairment of

grammar (taken here to mean principles of narrow syntax.) Their errors are restricted to those

cases that can be characterized as reliance on alternative means of building information

structure (in comprehension) or encoding a message (in production.) If this alternative is not

available, these patients will produce, perhaps slower than in unimpaired speech,

syntactically well-formed utterances.

A natural question is why functional categories are more vulnerable than lexical ones.

First of all, notice that omission of functional categories is compatible with some registers in

unimpaired language, while there is no register that would allow optional omission of a

lexical element (e.g. even if we know from a given context that the conversation is about a

specific boy who read some book, it is impossible to say "the ... read a ...") Simply speaking,

lexical elements are too informative to be omitted. In terms of Shannon's information theory

(Shannon 1948), these elements are selected from a larger set compared to the functional

categories, which makes them, in the technical sense, "more informative." Avrutin (in

preparation) provides more discussion of how a formal information theory can be integrated

into current psycholinguistic research. Suffice it to say that the amount of information an

element has is proportional to the degree of activation it receives, and therefore is less likely

to be omitted. The same kind of reasoning explains why in some languages aphasic patients

demonstrate substitution patterns rather than omissions. These are usually morphologically

rich languages; thus each form is to be selected from a larger set of related elements (a

somewhat similar, processing-based account is offered in Lapointe 1985.) This fact makes

17

them more informative, with direct consequences for processing cost and activation (for more

discussion of such relationship in unimpaired speech see, for example, Kostic et al (in press))

2.4.2. Comprehension

In order to illustrate how the proposed model explains comprehension deficiency in Broca's

aphasia, I will now discuss some experimental findings that can be straightforwardly

explained in terms of a competition between two systems. It is certainly beyond the scope of

this article to address all findings in aphasia; the ones presented below will simply serve as an

illustration of the application of the model.

A typical case where economy considerations determine a possible interpretation is

the so-called Exceptional Case Marking constructions (ECM) illustrated in Dutch example

(8) (SE stands for 'simplex expression: a monomorphemic element that is always referentially

dependent on an antecedent in the same sentence.)

8)

Jani zag [zichi / *hem i dansen]

John saw [SE/him dance]

Reuland (2001) in his Primitives of Binding framework argues that various types of anaphoric

dependencies form an economy hierarchy in such a way that a more costly dependency is

disallowed, provided a cheaper alternative is available. For example, Dutch anaphor 'zich' can

enter a syntactic dependency with its antecedent as a result of feature checking. Pronouns, on

the other hand, are unable to participate in this type of dependency because, unlike simplex

expression 'zich', they possess a number feature that cannot be deleted. Thus, no syntactic

dependency can be formed for a pronoun. There are, of course, other dependencies in natural

language, e.g., discourse dependency where 'Jan' and 'hem' would receive the same value

from discourse storage9:

9)

Jan zag hem dansen -------------> zag (x, (dansen (y)); x=y

John saw him dance

18

However, according to Reuland's hierarchy, a discourse dependency is more expensive than a

syntactic one. Thus, it is disallowed on the basis of economy considerations.

If the narrow syntax is "weakened" and is no longer the most economical option, the

hierarchy proposed by Reuland changes.

If so, there should be no prohibition against

establishing a non-syntactic dependency between the antecedent and a pronoun in (9).

Ruigendijk et al (2003) have recently demonstrated that indeed Dutch speaking Broca's

aphasics show an impaired pattern of responses. In a picture selection task, subjects were

presented with sentences such as in (10) and three pictures corresponding to the correct

choice of an antecedent, an incorrect one, and a filler.

Each sentence began with an

introductory clause of the form ‘First the boy and the man drank something and …’ (in order

to make two possible antecedents available) and concluded with the following:

10)

… daarna zag de man hem voetballen

[Dutch]

… then the man saw him playing soccer

The correct picture showed a boy playing soccer in front of the mirror, and a man looking at

the boy. The incorrect picture showed a man playing soccer in front of the mirror looking at

himself. Thus, if a listener disallows coreference between 'him' and 'the man', he/she should

choose the correct picture. If he/she allows 'him' to refer to the matrix subject, the incorrect

picture could be chosen.

Adult controls correctly chose the picture where the man sees the boy in the mirror.

Aphasic speakers, however, incorrectly pointed to the picture where the boy sees himself

around 50% of the time, which is not different from chance10. In other words, they quite often

allowed a local dependency relation between the pronoun and the matrix subject. The authors

argue that since the syntactic dependency is the less economical one for this population, they

may sometimes allow a semantic or discourse dependency between the matrix subject and the

pronoun. Notice that such allowance is once again "optional" -- it is not the case that subjects

19

always select this picture.

This is not surprising, however, because, as in the case of

production, the errors result from the competition between two systems -- the narrow syntax

and an alternative that is the context. For some speakers, one system can win on some

occasions, and the other will take over in other cases, which results in an overall chance

performance11.

The above results show that Broca's aphasics sometimes fail to establish a

dependency relation between an antecedent and a pronoun correctly.

Other results

concerning dependency between two positions involve passive constructions and object

relatives. The abnormal, chance-level comprehension of agrammatic Broca's aphasics on

passive constructions is well known. As discussed extensively in Grodzinsky 1990,12 a

typical observation is that Broca's aphasics choose at a more or less chance level between 'the

cat' and 'the dog' as the agent of the chasing event in the following sentence.

11) The cat was chased by the dog.

Grodzinsky's trace deletion hypothesis (TDH) suggests that aphasic patients are unable to

represent traces, so a trace in the object position of the verb 'chase' is deleted. As a result, the

subject DP does not receive the agent theta-role (as it should in an unimpaired linguistic

structure), and, since each DP must have a theta role in order to be interpreted, the subject

receives an interpretation by means of some kind of strategy that assigns, at least in English,

the agenthood to the first DP in the sentence. Alternative explanations for this phenomenon

were offered, among others, by Piñango (1999) who argues that the impairment is restricted

to mapping between syntactic and semantic structures.

Notice however that the phonologically empty element in the object position (a trace,

or a copy) normally enters a syntactic dependency with the subject. This dependency may be

represented as a syntactic chain, or as some other mechanism that would link the two

positions in narrow syntax. I suggest, however, that such dependency must be established in a

20

timely fashion, that is very fast, in a normal case, in order to function as a reliable source of

interpretation. Syntactic operations, however, are slowed in aphasia, as demonstrated

convincingly by Zurif et al (1993) and Swinney (2003)13. These researchers showed that

Broca's aphasics show priming for an antecedent significantly later than normal controls. The

main point thus is that the syntactic dependency is, in principle, intact in aphasia; however,

the necessary syntactic connection is significantly slowed down14. In terms of the proposed

model, we can interpret these findings as evidence for the lack of necessary resources for

conducting syntactic operations in time because, as in any other physical system, speed is a

function of available energy; in other words it is proportional to the available brain activation.

As the syntactic system is no longer the most economical (and hence the cheapest one) for

these patients, they may sometimes avoid reliance on narrow syntax when interpreting

passive constructions. As the first DP in a passive construction is usually the most prominent

element, a topic, and as there is a general correlation between topichood and agency (as also

pointed out by Grodzinsky in his formulation of aphasics strategy), the information unit

introduced by the first DP may end up marked as the agent. Once again, there is a

competition between the two systems. Depending on which system wins, patients will either

choose a correct interpretation (subject=patient), or an incorrect one (subject=agent.)

Overall, we observe a chance performance15.

Finally, the proposed model makes the prediction that the chance performance in

comprehension will be observed in Broca's aphasics only in cases where

competition

between the syntactic and discourse-related operations may take place. As discussed above

for production, when no alternative is possible, and the application of a syntactic operation is

required, these patients are predicted to show an above chance performance. A clear example

of such a situation in comprehension is the case of wh-questions. Hickok and Avrutin (1995)

21

and Tait et al (1995) show that Broca's aphasics performed above chance on object WHOquestions (as in (12)) but around chance on object WHICH-questions (as in (13))16.

12) Who did the cat chase?

13) Which dog did the cat chase?

WHO-questions differ from WHICH-questions in that only the latter is discourse-linked.

Specifically, the wh-phrase 'who' functions as a pure operator and is not represented by a

discourse referent.

The wh-phrase 'which dog', on the other hand, does have such a

representation, since it presupposes the existence of a known set of dogs. Importantly, thus,

only in (13) is a discourse link between the object position and the wh-phrase is possible; for

who-questions the only option is to establish the connection in syntax. Broca's aphasics

demonstrated a good performance on the "pure syntactic" question, while showing a chance

performance on the condition where a competition between two systems (syntactic and nonsyntactic) was in principle possible. Given that their syntactic system was weakened, they

would occasionally rely on a non-syntactic one, which resulted in a an overall chance

performance in the same way as in the case of interpreting ECM constructions or passive

sentences.

4. Summary

As a result of damage to Broca's region, the amount of resources necessary for

conducting operations involving narrow syntax is diminished. This causes a slow down in

the process of speech production.

Moreover, reduced power of this system (a direct

consequence of diminished resources) may result, at least sometimes, in the situation where

alternative systems become more powerful, and therefore are used for the purposes of

building information structure in comprehension, or encoding a message (in production: an

option available, in principle, in unimpaired language.17)

22

Impairment in Broca's aphasia is not limited to structures involving constituent

movement (e.g. passive constructions, object relative clauses.) Comprehension of pronouns

and other determiners causes difficulties as well. Slow, effortful, telegraphic speech is

characteristic of the same patients who demonstrate problems with comprehension of certain

elements. The unified explanation of these phenomena presented here is based on the claim

that the power of the damaged Broca's region is diminished, with direct consequences both

for production speed and economy-based errors in comprehension.

In order to produce speech in normal time, and to rely on narrow syntax for the

purposes of conveying and processing information, speakers need to have strong, powerful

syntactic apparatus capable of performing required operations in time. As a result of brain

damage, the power available to this system is reduced, and the syntax becomes weak.

23

References

Akmaijan, A. 1984. Sentence type and form-function fit. Natural Language and Linguistic

Theory, 2, 1-23.

Avrutin, S. 1999. Development of the syntax-discourse interface. Dordrecht, Kluwer

Academic Publishers.

Avrutin, S. 2000. Comprehension of D-linked and non-D-linked wh-questions by children

and Broca’s aphasics. In: Language and the brain (Y. Grodzinsky, L. Shapiro and D.

Swinney, Eds.), San Diego, Academic Press, 295-313.

Avrutin, S. 2004. Optionality in child and aphasic speech. Lingue e Linguaggio, 1, 67-89.

Baauw, S. E. de Roo, and S. Avrutin. 2002. Determiner Omission in Language Acquisition and

Language Impairment: Syntactic and Discourse Factors. Proceedings of the Boston

University Conference on Language Development. Boston, Cascadilla Press, 23-35.

Bastiaanse, R. and R. Jonkers. 1998. Verb retrieval in action naming and spontaneous speech

in agrammatic and anomic speech. Aphasiology 12, 951-969.

Bastiaanse, R. and R. van Zonneveld. 1998. On the relation between verb inflection and verb

position in Dutch agrammatic aphasics. Brain and Language, 64, 165-181.

Benedet, M.J., Christiansen, J.A. and H. Goodglass, H. 1998. A cross-linguistic study of

grammatical morphology in Spanish- and English-speaking agrammatic patients. Cortex,

34, 309-336.

Blom, E. 2003. From root infinitive to finite sentences. Doctoral dissertation, Utrecht

University, The Netherlands.

Caramazza, A. and E. Zurif. 1976. Dissociation of algorithmic and heuristic processes in

language comprehension: Evidence from aphasia. Brain and Language, 3, 572-82.

Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on government and binding, Dordrecht, Foris.

24

Chomsky, N. 1986. Knowledge of Language, New York, Praeger.

Chomsky, N. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MIT Press.

De Roo, E. 1999. Agrammatic Grammar, Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University.

Enç, M. 1991. Anchoring Conditions for Tense. Linguistic Inquiry, 18, 633-57.

Friedmann, N. 1999. Functional categories in agrammatic production: a cross-linguistic

study. Doctoral dissertation, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

Grodzinsky, Y. 1990. Theoretical perspectives on language deficit. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Grodzinsky, Y., A. Pierce and S. Marakowitz 1991. Neuropsychological reasons for a

transformational derivation of syntactic passive. Natural Language and Linguistic

Theory.

Grodzinsky, Y. 1999. The neurology of syntax: Language use without Broca’s area. Brain

and Behavioural Science, 23, 47-117.

Grodzinsky, Y., K. Wexler, Chien, Y.-C., S. Marakovitz & J. Solomon. 1993. The breakdown

of binding relations. Brain and Language, 45, 371-395.

Gueron, J. & T. Hoekstra. 1995. The temporal interpretation of predication. In Syntax and

Semantic 28 (A. Cardinalletti and T. Guasti, Eds.), San Diego, Academic Press.

Haegeman, L. 1990. Understood subjects in English diaries: on the relevance of theoretical syntax

for the study of register variation. Multilingua, 9, 157-99.

Heim, I. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases, Doctoral

Dissertation, Amherst, University of Massachusetts.

Hickok, G. and S. Avrutin. 1995. Representation, Referentiality, and Processing in

Agrammatic Comprehension: Two Case Studies. Brain and Language, 50, 10-26.

Hofstede, B. 1992. Agrammatic speech in Broca’s aphasia; Strategic choice for the elliptical

register, Doctoral dissertation, Nijmegen Institute for Cognition and Information.

Kamp H. and U. Reyle 1993. From Discourse to Logic, Dordrecht, Kluwer Academic.

25

Kolk, H. 2000. Canonicity and inflection in agrammatic sentence production. Brain and

Language, 74, 558-560.

Kolk, H.H.J. and C. Heeschen 1992. Agrammatism, paragrammatism and the management of

language. Language and Cognitive Processes, 7, 89-129.

Kolk, H.H.J. 1998. Disorders of syntax in aphasia. In: Handbook of neurolinguistics (B.

Stemmer and H. Whitaker, Eds.), San Diego, Academic Press, 249-260.

Kolk, H.H.J. 1995. A time-based approach to agrammatic production, Brain and Language,

50, 282-303.

Kostic, A. (in press) The effects of the amount of information on processing of inflected

morphology. Manuscript, University of Belgrade.

Levelt, W.J.M. 1989. Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge, MIT Press.

Lapointe, S. 1985. A theory of verb form use in the speech of agrammatic aphasics. Brain

and Language, 24, 100-185.

Lonzi, L. and C. Luzzatti. 1995. Omission of prepositions in agrammatism and universal

constraint of recoverability, Brain and Language, 51, 129-32.

Love, T., J. Nicol, D. Swinney, G. Hickok & E. Zurif. 1998. The nature of aberrant

understanding and processing of pro-forms by brain-damaged populations. Brain and

Language, 65, 59-62.

Piñango, M. 1999. Syntactic displacement in Broca’s aphasia comprehension. In:

Grammatical disorders in aphasia: a neurolinguistic perspective (Y. Grodzinsky and

R. Bastiaanse, Eds.), London, Whurr, 75-87.

Piñango, M.M. 2000. Neurological underpinnings of binding relations. Paper presented at the

linguistic society of Germany, Marburg, Germany, March 2.

26

Piñango, M., P. Burkhart, D. Brun and S. Avrutin. 2001. The Architecture of the Sentence

Processing System: The Case of Pronominal Interpretation. Paper presented at

SEMPRO meeting, Edinburgh, UK.

Piñango, M. and P. Burkhardt. 2001. Pronominals in Broca’s aphasia comprehension: the

consequences of syntactic delay. Brain and Language, 79, 1, 167-68.

Reuland, E. 2003. A window into the architecture of the language system.

GLOT International, 7, No 1/2.

Reuland, E. 2001. Primitives of binding. Linguistic Inquiry, 32, 439-92.

Ruigendijk, E. 2002. Case assignment in Agrammatism. Doctoral dissertation, Groningen

University.

Ruigendijk, E., S. Baauw, S. Zuckerman, N.Vasić, J.de Lange and S. Avrutin. 2003. A crosslinguistic study on the interpretation of pronouns by children and agrammatic

speakers: Evidence from Dutch, Spanish, and Italian, Paper presented at CUNY

sentence processing conference, Boston.

Shapiro, L. and B. Levine. 1990. Verb processing during sentence comprehension n aphasia.

Brain and Language, 38, 21-47.

Shapiro, L., Zurif, E. and J. Grimshaw. 1987. Sentence processing and the mental

representation of verbs. Cognition, 27, 219-246.

Swinney, D. J. Nicol & E. Zurif. 1989. The effects of focal brain damage on sentence

processing: an examination of the neurological organization of a mental module.

Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 1, 25-37.

Swinney, D. 2003. Psycholinguistic approaches. Paper presented at the 4th Science of

Aphasia conference, Trieste.

Tait, M.E., Thompson, C.K. and K.J. Ballard. 1995. Subject-object asymmetries in

agrammatic comprehension of four types of wh-questions. Brain and

27

Language, 51, 77-79

Tesak, J. and J. Dittmann. 1991. Telegraphic style in normals and aphasics. Linguistics, 29,

1111-37.

Vallduví, E. 1992. The informational Component, New York, Garland.

Zurif, E.B. 2003. The neuroanatomical organization of some features of sentence processing:

Studies of real-time syntactic and semantic processing. Psychologia, 32, 13-24.

Zurif, E.B., D. Swinney, P. Prather, J. Solomon and C. Bushell. 1993. An on-line analysis of

syntactic processing in Broca’s and Wernicke’s aphasia. Brain and Language, 44864.

Wenzlaff, M and H. Clahsen (in press). Finiteness and Verb-Second in German

Agrammatism.

28

Narrow Syntax

Information structure

Context

(" linguistic discourse",

"C-I interface")

D: a

FRAME

NP: information

?

Heading: dog

dog

Fig. 1: Normal way of introducing an individual information unit for DP 'a dog'.

Narrow Syntax

Information structure

Context

(" linguistic discourse",

"C-I interface")

T:

FRAME

?

past tense features

VP: information

Heading: run

ran

Fig. 2: Normal way of introducing an Event Unit of information.

29

Context

Special registers:

Individual frame encoded through presupposition

Information structure

(message)

(" linguistic discourse",

"C-I interface")

FRAME

Heading: meisje

Narrow Syntax

NP: information

meisje ('girl')

Fig. 3. Non-syntactic way of encoding an individual frame.

30

Context

Special registers:

Event frame encoded through presupposition

Information structure

(message)

(" linguistic discourse",

"C-I interface")

FRAME

Heading: prygat' (to jump)

Narrow Syntax

VP: information

Prygat' (to-jump)

Fig. 4. Non-syntactic way of encoding an event frame.

31

*

The preparation of this publication was supported by the Dutch National Science

Foundation (NWO) as part of the Comparative Psycholinguistics research program. I thank

Sergio Baauw, Yosef Grodzinsky, Joke de Lange, Esther Ruigendijk, Nada Vasic and Shalom

Zuckerman for their comments. Special thanks are due to Jocelyn Ballantyne for proofreading the manuscript.

1

For example, Grodzinsky et al (1991) used evidence from Broca's aphasics to distinguish

between two theories of passive constructions. They demonstrated that these patients are

selectively impaired in those constructions that, according to one of the competing theories,

involve syntactic transformations.

2

Haegeman (1990) also shows that omission of subjects in a non-pro drop language such as

English is possible in some specific "diary style" registers.

3

Recent work by Cole et al 2001 is particularly interesting in this regard as it shows that the

choice of an antecedent for a logophor can be parameterised with value of parameters

different in different dialects. This evidence demonstrates that the level of "discourse" is,

indeed, linguistic in nature and that the term "linguistic discourse" is rather appropriate.

4

I put a question mark under "context" as I remain agnostic with regard to the type of

symbols and the structure of context as a cognitive system.

5

In this sense, the notion of economy that has played a major role in recent theoretical work

(e.g. Chomsky 1995, Reuland 2001) is more than a formal notion. In my view, it should

reflect, at some level, the amount of resources utilized by the brain when performing a

specific computation. In Avrutin (2000) I discuss experimental evidence supporting the claim

that the narrow syntax operations are the cheapest. For further evidence see also Piñango et al

(2001).

32

6

The reduction of resources, and a consequent slow-down of the syntactic machinery are

most likely due to problems with lexical access in Broca's aphasia, as argued by many

researchers (e.g. Zurif 2003, Shapiro and Levin 1990, Swinney et al 1989, among others.)

7

For a somewhat different explanation of these data see Ruigendijk (2002).

8

The same approach explain the omission of complementizers in aphasics' speech. Since

Comp and T form a chain, omission of one element necessitates omission of the other in

order to avoid an invalid chain formation.

9

Once again, there is a discrepancy in terminology. What Reuland (2001) refers to as

"discourse dependency" is, in my terminology, a dependency at the level of information

structure ("linguistic discourse") established by reliance on contextual information. Reuland's

notion of

"discourse storage" should be viewed as part of the context in the present

terminology.

10

When in the same construction the pronoun is replaced with 'zichzelf', the patients

demonstrated an almost perfect performance. Thus, their problem is not related to ECM

constructions per se, but rather to the interpretation of a pronoun in such constructions.

11

Another reason is that there is always a choice between two pictures; that is even if

subjects allow for a discourse dependency between the matrix subject and the pronoun, they

don't have to make this choice: it is always possible to interpret the pronoun as referring to an

external antecedent.

12

Grodzinsky (1999) provides a more general picture of the role of Broca's area in

comprehension of structures involving transformations. For expository purposes, I will focus

here on passive constructions, although, I believe, the account can be extended to relative

clauses and clefts.

13

Other results that are relevant are reported in Swinney et al 1989 who showed that Broca's

aphasics exhibit abnormal pattern of activation of word meaning. In a study with ambiguous

33

words, these researchers show that Broca's aphasics are capable of accessing only the most

frequent meaning of the word within the initial, short period of time. Later on, however, both

meanings become available.

14

Further evidence that Broca's aphasics maintain a normal ability to connect two position in

a syntactic tree but in a slower-than-normal way is presented in Piñango and Burkhardt

(2001).

15

The same explanation also holds for the chance performance observed in object relative

clauses, as in pioneering work of Caramazza and Zurif (1976).

16

Performance on both types of subject wh -questions was above chance, as predicted

because in this case the information about the thematic role of the unmoved object is

sufficient to obtain a full interpretation.

17

Another population that exhibits performance similar to that of Broca's aphasics is

normally developing children. See Avrutin (2004) for more discussion and the application of

the proposed model to child speech.

34