Jackson`s Knowledge Argument

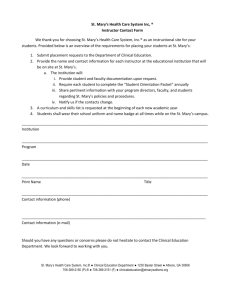

advertisement

Philosophy of Mind: First Essay Wylie Breckenridge The Knowledge Argument against Physicalism Physicalism is the belief that mental events and their properties are entirely physical and can be described in the same objective physical way as all other phenomena in the world. The physicalist program has had a certain amount of success describing and explaining functional aspects of the mind, but the subjective nature of mental experience has remained elusive. Some believe that physicalism must fail here, and have put forward various arguments about 'zombies' and 'inverted qualia' to that effect 1. Other arguments against physicalism are knowledge-based. If physicalism is true, then a complete physical description of mental states must contain all the information there is to know about those states. In 'the knowledge argument', Frank Jackson claims to show that this is not the case: that there are facts about subjective experience of mental states not entailed by a complete physical description2. In this essay I will present Jackson's argument and some of its objections, and discuss the extent to which they are successful. Jackson's argument Jackson asks us to imagine Mary, a brilliant scientist confined to a room in such a way that everything she sees is in black and white3. Mary specialises in the neurophysiology of vision, and (via her black and white television) she obtains all the physical information possible about colour vision. Jackson allows that she is brilliant enough to follow through all the logical consequences of her knowledge, so that anything it is possible for her to know in this way in principle, she knows in actuality. Jackson argues that if Mary was to leave her room and look at, say, a ripe tomato, she would learn something new about seeing red - she would learn what it is like to see red, something that she did not know, and could not possibly have known, within the confines of her black and white room. Thus, concludes Jackson, there are facts about seeing red that cannot be described in physical terms. Physicalism is false. It will be helpful to present the argument in a way similar to a later presentation by Jackson4: P1 P2 C Before leaving the room, Mary knows everything physical there is to know about seeing red. Before leaving the room, Mary does not know everything there is to know about seeing red. There are truths about seeing red that escape the physicalist story. A number of objections have been raised against this argument. I will look in detail at those proposed by Paul Churchland1, Laurence Nemirow2 and David Lewis3. Firstly, all 1 For a concise account of these see Chalmers, D.J. (1996), The Conscious Mind (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 94 - 101. 2 His argument is presented in Jackson, F. (1982), 'Epiphenomenal Qualia', Philosophical Quarterly, 32, pp. 127-36. 3 Jackson, p. 130. 4 Jackson, F. (1986), 'What Mary Didn't Know', In David M. Rosenthal, ed., The Nature of Mind (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 392-4. -1- three have claimed that the argument is invalid because Mary only gains an ability when she leaves her room, not knowledge of a fact. Secondly, Churchland and Lewis suggest that the consequences of the knowledge argument are strange and therefore that it must be flawed in some way. Finally, Churchland, and to some extent Lewis, raise doubts about the truth of premise P2, suggesting that, contrary to intuition, Mary's complete physical knowledge might indeed lead her to know what it is like to see red within her black and white room. The ability objection Proponents of this objection argue that when Mary first sees red what she learns is an ability and not a fact about seeing red. Nemirow4 suggests it is an ability to imagine. He proposes what he calls the 'ability equation', that 'knowing what it's like' can be identified with 'knowing how to imagine'. He arrives at this by considering what someone would do if asked if she knows what seeing chartreuse is like: she would try to imagine it. Nemirow appeals to its explanatory power to support his equation: it debunks the knowledge argument, it explains how the equivocation error could arise, and it explains why Mary's physical knowledge was unable to describe what it is like to see red. Lewis refines this into what he calls 'the ability hypothesis', that 'knowing what it's like' is having the ability to remember, imagine or recognize an experience while also knowing that it is that experience. There is a difference in the details of what Nemirow and Lewis think the ability 'knowing what it's like' is, but they agree on the basic point that it is an ability, not factual knowledge. If this is true, it renders the knowledge argument invalid. Churchland tries to make this clear by recasting the argument in the following way5: Pa Pb C* Before leaving the room, Mary knows everything there is to know about brain states and their properties. Before leaving the room, it is not the case that Mary knows everything there is to know about sensations and their properties. Sensations and their properties brain states and their properties. He claims that Jackson is using an argument that appeals to Leibniz's law, but that it is invalid because the premises equivocate on the meaning of 'knows about'6. Jackson agrees that that is true of the above argument, but claims that Churchland's 1 Churchland, P.M. (1985), 'Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States', The Journal of Philosophy, 82, pp. 8-28. 2 Nemirow, L. (1990), 'Physicalism and the Cognitive Role of Acquaintance'. In W. Lycan, ed., Mind and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 490-99. 3 Lewis, D. (1990), 'What Experience Teaches'. In W. Lycan, ed., Mind and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 499-519. 4 Nemirow, p. 492. 5 Churchland, p. 23. 6 Put simply, Leibniz's law says that if A is identical with B then every property that A has B has, and vice versa. So if A and B differ in at least one property then they cannot be identical. What counts as a property is usually given some qualification, such as being intrinsic and non-relational. In any case, Churchland's objection here is that the property 'is known about' has a different meaning in each premise, and that this rules out the use of Leibniz's law. -2- reformulation is not the knowledge argument. Nevertheless, the objection that what Mary learns is 'know-how' rather than 'know-that' poses a problem for Jackson's formulation, because it assumes that what Mary learns is a fact about seeing red. So if all she learns is an ability, then the argument collapses. The 'strange consequences' objection Churchland objects that if the knowledge argument was sound it would prove too much, for it would rule out dualism as well1. He asks us to think instead of Mary as an 'ectoplasmologist' who has learned all there is to know about a nonmaterial substance, called 'ectoplasm', that forms the basis of all mental phenomena. Mary would still not know what it is like to see red until she leaves the room, so even dualism is inadequate to account for mental phenomena. He uses this to cast doubt on the original knowledge argument. Jackson has a simple and effective reply2: that when used as an argument against dualism premise P1 is implausible. We can imagine how Mary might learn all the physical facts about colour vision from within her black and white room, but how could she possibly learn all about nonmaterial ectoplasm? Lewis considers in more detail what would follow if the knowledge argument was sound3. It would mean that as well as there being physical information about mental states, there would also be an independent type that he calls 'phenomenal information'. But, like Churchland, he claims that no theory, not even a complete theory about nonphysical mental states, could inform Mary about what it's like to see red, so that this 'phenomenal information' is somehow forever beyond her reach. He shows that it is strange in another way: that phenomenal information could not explain why people talk about the phenomenal aspect of the world. Suppose Mary leaves her room and discovers the piece of phenomenal information 'what it's like to see red'. Suppose that afterwards she writes about her discovery, trying to put in words what it's like. Then to claim that this behaviour is caused by the particular piece of information she discovered is to claim that something non-physical can effect the motion of physical objects (i.e. the particles in Mary's body). But that throws into question all we believe about Physics. To avoid that we must conclude that Mary would have behaved in the same way, even if the information she discovered about seeing red was different, or even if she had discovered nothing at all! Lewis argues that such strange consequences suggest the knowledge argument is flawed. The 'perhaps she does know' objection A third type of objection is that premise P2 might be false. How could that be? It would be false if Mary already knew what it was like to see red before she saw her first ripe tomato. Lewis hints at this: Having an experience is surely one good way, and surely the only practical way, of coming to know what that experience is like. Can we say, flatly, that it is the only possible way? 1 Churchland, p. 24-5. Jackson, 1986, p. 394. 3 Lewis, p. 511-14. 2 -3- Probably not. There is a change that takes place in you when you have the experience and thereby come to know what it's like. Perhaps the exact same change could in principle be produced in you by precise neurosurgery, very far beyond the limits of present-day technique.1 He goes on to suggest that states produced in this artificial way may well deserve to be called 'knowing what it's like', and that science lessons might one day be able to replace direct experience as a way of learning about the subjective 'feel' of mental states. Churchland takes this point seriously. He claims that Jackson has not "adequately considered how much one might know if, as the first premise asserts, one knew everything there is to know about the physical brain and nervous system"2. He says that this is "of profound importance for understanding one of the most exciting consequences to be expected from a successful neuroscientific account of the mind". Churchland thinks we can imagine how neuroscientific information would give Mary detailed information about the qualia of various sensations. By learning about the structure of musical sound, musicians come to hear individual notes within chords that previously sounded like unstructured wholes. This discriminative ability allows them to create and imagine new chords within their heads, and to know what they sound like before hearing them played. Why might the same not be possible with colours? This possibility is made more plausible by the finding that colours have a similar structure to musical notes. Churchland concedes that the physical structure of Mary's brain will limit what she can imagine in this way, but within that limitation it may "soar far beyond" what Jackson suspects. How the objections fare I don't think that the ability objection works. Its proponents claim that 'knowing what it's like to see red' is just an ability, and not knowledge of a fact. But consider instead 'knowing the name of the Prime Minister'. What would someone do if asked if he knew the name of the Prime Minister? He would try to perform certain mental acts remembering or deducing or something else. If he could get his mind into a certain state, then he would claim to know. So the objectors would have to also allow that 'knowing the name of the Prime Minister' is an ability. But this is knowledge of a fact the fact 'the name of the Prime Minister'. So why can't 'knowing what it's like to see red' be both an ability and knowledge of a fact - the fact of 'what it's like to see red'? The objection that the knowledge argument also rules out dualism doesn't work. Jackson's reply makes this clear - when used as an argument against dualism, the first premise, that Mary has a complete knowledge of dualist theory, is simply implausible. Lewis' objection, that the knowledge argument is doubtful because it has strange consequences, does not appeal to me. I think that he's right, but I'm not prepared to use strangeness as a measure of truth and falsity. If I did, then I'd have good reason to doubt much of modern physics. 1 2 Lewis, p. 500. All of Churchland's quotes in this paragraph are taken from Churchland, p. 25. -4- I think that the third type of objection provides hope of saving physicalism from Jackson. His argument assumes that even if Mary had a complete knowledge of the neurophysiology of colour vision, and all its logical consequences, she would still not know what it is like to see red. This is not obvious. Churchland's analogy of knowledge of musical theory should raise some doubt about this. Consider, also, what Mary does when she deduces the logical consequences of her knowledge: she uses existing brain states and certain cognitive abilities to produce new brain states. Why couldn't one of those brain states be the state of knowing what it's like to see red? As difficult as this might be to imagine, until we have good reason to believe that it is impossible then we should not rule it out. It can't be the case that both physicalism is true and the knowledge argument is sound. However, physicalism is attractive because we've had so much success describing the non-mental world in objective physical terms, and the knowledge argument is persuasive because it appeals to our intuitions about the nature of subjective experience. At the heart of the problem is our limited understanding of what this experience is. It seems to me that until this understanding improves, the problem will remain intractable. Bibliography Chalmers, D.J. (1996), The Conscious Mind (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 94 - 101. Churchland, P.M. (1985), 'Reduction, Qualia, and the Direct Introspection of Brain States', The Journal of Philosophy, 82, pp. 8-28. Jackson, F. (1982), 'Epiphenomenal Qualia', Philosophical Quarterly, 32, pp. 127-36. ________. (1986), 'What Mary Didn't Know', In David M. Rosenthal, ed., The Nature of Mind (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 392-4. Lewis, D. (1990), 'What Experience Teaches'. In W. Lycan, ed., Mind and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 499-519. Nemirow, L. (1990), 'Physicalism and the Cognitive Role of Acquaintance'. In W. Lycan, ed., Mind and Cognition (Oxford: Blackwell), pp. 490-99. -5-