wc1 Medieval Monastery life ch 9

advertisement

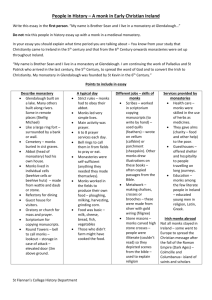

Mr. Balazs W. Civ. 1 The below article was written in 2005 by a writer who chose to spend a weekend at a Monastery. Monastery life in 2005 is similar to monastery life in 1005, in that it is simple, but of course 1000 years ago many creature comforts that exist today didn’t exist. It’s almost certain that the monks would share beds, eat far simpler foods and prayed far more. On the other hand even in the middle ages, travelers often stayed at monasteries. Answer the following questions based on the reading: 1. Describe life in the monastery. 2. Why did the writer want to stay at a Monastery. 3. How did the Monks dress and groom themselves? 4. Briefly explain what you like about life in this monastery? 5. Why aren’t women allowed in the below monastery? 6. What was unusual about the dinner time meal? 7. What do you find the most interesting aspect of life in the below described monastery? 8. Today few people become monks or nuns, in the Medieval ages many did, why do you think they entered into a life of religious solitude? A Quiet Weekend With the Monks Sam Hooper Samuels. New York Times NO one met me at the door of the guesthouse of the Most Holy Trinity Monastery in Petersham, Mass., when I arrived late on a snowy Friday afternoon. A handwritten cardboard sign directed me down a dimly lighted hallway to Room 4, a 12-foot square with a single bed, a small writing desk and two wooden armchairs. Behind me were jangling telephones, insistent e-mail, commuting, computing, family obligations, deadlines and miscellaneous noise. Suddenly, silence. Absolute, dead silence. My spiritual retreat -- 45 hours in a community of contemplative monks, part of the Eastern Catholic Maronite order -- had begun. Staying at a monastery, an abbey or a convent is not a new notion. ''Let all guests who arrive be received like Christ,'' says the 6th-century Rule of St. Benedict, the blueprint for daily life used by Benedictine monasteries and adapted by other orders. (The rule also suggests that on my arrival and departure, the superior might have bowed his head or even prostrated (to lie face down) himself on the ground in adoration of Jesus, who is received in my person, but the cardboard sign was fine.) Cloistered vacations are a growing trend, with more and more lay people taking weeklong or weekend retreats to rejuvenate the spirit. Monasteries and retreat centers are in every state and in many flavors: Catholic, Buddhist, Jewish, secular. Some are booked months ahead. Most Holy Trinity is small, with 11 monks and room for eight retreat guests (women are not allowed), and utterly remote, on a secluded driveway at the end of a mile of steep dirt road. Its’ jumble of structures are connected by covered walkways and passages, some of which I discovered are not heated. Above my bed was a crucifix, and I was provided with a Bible and printed material outlining the routines. I had my own bathroom, also an alarm clock. I would need that. Morning prayers are at 5:20. The rules are simple. I could walk around the grounds, provided I didn't stray into areas of ''monastic enclosure.'' (I would never see a monk's own cell.) I could write on paper, but laptops and other electronic devices were taboo. Above all, I was to be silent. Perfect. I unpacked and went to explore the guesthouse's small library, where I found a copy of ''Forty Years Behind the Wall,'' a memoir by one Father M. Raymond of his life at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky, home of the monk and author Thomas Merton. On the cover, Father Raymond smiled enigmatically through thick glasses. ''Hi!'' the book's forward began. ''Do you want to read a book that is different? You do? Well, read on.'' If Father Raymond could maintain this level of cheery good will for 40 years, my two days would be a snap. Suppertime. At Most Holy Trinity, the retreat guests eat with the monks. Some were already at their places when I arrived, black habits flowing loosely to the floor. Over their heads were close-fitting black hoods. All wore beards, from the jet black of a few apparently in their 30's to the pure white of the abbot. A napkin ring marked ''Room 4'' marked my place. The meal was simple. Butternut squash soup. Bread. A tub of trans fat-free margarine. Monastery yogurt (do not stir). An open jar of Skippy peanut butter, creamy. Tea, coffee, juice, milk, water. There was no ''excuse me'' or ''after you'' in the buffet line; politeness was conveyed by nods, glances and smiles. Seats were along one side of each table, with no face-to-face contact. The stools were hard and had no backs. We ate with no sound but the clink of dishes. Finished in five minutes, I was glad books were allowed. I spent the rest of the allotted half hour sipping tea with Father Raymond for company and resolved to practice eating more slowly. Then it was nearly time for evening prayer. In a monastery, it's always nearly time for some prayer or other. The candlelit church was an imposing space. Between soaring, beamed ceilings and rough stone floors hung the sweet, penetrating odor of incense. An iron railing marked off a visitor area. On the other side, the monks chanted their prayers in English, with occasional forays into Aramaic (similar to Latin, an ancient language no longer used). I am Jewish. Although non-Catholics do not take communion, they are welcome to attend the four services each day. Over my two days, I spent hours in this church, fervent chants reverberating around me, increasingly moved by the monks' devotion and their willingness to share it with guests. (1000 years ago, much less 50 years ago non-Christians would not be allowed to stay in a Christian monastery) Outside church, I saw them rarely except at the silent meals -- oatmeal at breakfast, simple hot dishes at dinner. I came to enjoy the smiles and nods and lack of small talk. As the weekend passed, hours that once would have clamored to be filled felt better and better empty. Or perhaps they were just filling from a different source. At night I slept deeply. Like the monks, I spent much of the day reading. I had brought ''Peace Is Every Step'' by Thich Nhat Hanh, a Vietnamese Zen monk. ''The Cookie of Childhood,'' an essay recalling that at age 4 he had made a single cookie last 45 minutes, gave me heart in my struggle to eat more meditatively. On Saturday, bundled against the bitter cold, I ventured out for a walk. Silence seemed to emanate from this place, reaching far into the fields and woods. I had nearly finished circumnavigating the monastery when a young monk walked up the drive toward me, his long habit peeking out below the hem of a sturdy, utilitarian winter coat. Softly, he spoke, bending the rule of silence to correct me. ''The enclosure actually begins over there,'' he said, pointing toward an imaginary line, cloistering the monks, which I had crossed. I apologized, and he smiled gently. Inside, I found the guest master imparting a goodbye blessing to four retreat participants who were about to leave early, driven by a blizzard warning on the monastery's weather radio. A sharp realization struck me. I desperately didn't want my retreat to be cut short. After just 24 hours, I had begun to forget the world outside, and at the risk being snowed in, I was staying. The guest master spoke briefly with me -- apparently one of the perks of the job is an occasional hushed conversation. I had seen a small shack in the woods. Was that a hermitage? It was, he told me. There were more than one, but nobody used them. ''The carpenter ants live in them, the porcupines live under them, and the squirrels are all over them,'' he said. ''In the winter, you have to feed the wood stove all day. In the summer, you have to cut fuel for the wood stove all day.'' More monks might choose a hermit's existence, he speculated, if they had electric heat. ''Maybe we're spoiled.'' Spoiled. My very thought. By now the monastery was making its way into my muscles, into my bones. I found myself walking slower, feeling taller, breathing deeper. I didn't skim; I read. My handwriting became legible. One other retreat guest remained -- a handsome, 50ish man with black hair and perfect posture. We passed each other in the hallways with silent smiles. Twice at Mass, he passed a blessing to me by touching fingertips. Don't ask me his name. Inevitably, Sunday arrived, and I felt a nasty case of the spiritual bends coming on. After our last attendance at prayers, the abbot invited us guests, by a silent nod, to use the monks' exit. A simple gesture, but I felt honored. THE midday dinner, too, was a special occasion, with meatloaf in gravy and a berry cobbler. The usual silence was broken by a taped sermon: as savory mouthfuls crumbled against my tongue, a disembodied but mirthful voice explained the nuances of sins of the flesh. Hooded heads nodded in agreement; bearded faces smiled when the speaker got in a good one. After precisely 30 minutes, a hand bell was rung and the tape was stopped in midsentence. My retreat was finished along with the meal, but I had eaten for the full half hour and tasted every blessed bite. Nearly two feet of snow had fallen, but monks with snowplows had cleared a path. Invisible hands had even brushed my Honda Civic clean. An almost blinding white light glinted off the new-fallen snow as I drove away. In the car, I turned on a taped book. Then I turned it off again, preferring the silence.