doc - WordPress.com

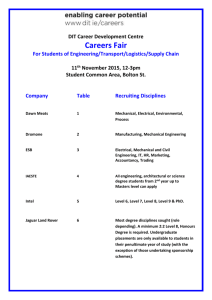

advertisement

Critical Technical Practice as Interdiscipline Paul Dourish Informatics University of California at Irvine jpd@ics.uci.edu INTRODUCTION We are both trained in Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence (AI) and have moved over the course of our careers ever closer to the critical social sciences. We are now senior scholars loosely associated with HumanComputer Interaction (HCI) but maintaining ties as well to Science & Technology Studies, Design, Media Studies, and Anthropology. In this work, we have been significantly influenced and inspired by Agre’s notion of critical technical practice [1]. One of the flavors of our work is critical analysis tied deeply to technical understanding; another (perhaps dwindling) flavor is designing and implementing computational systems that reflect critical alternatives to mainstream approaches. One of the goals of each of our careers has been to get technical conversations to be more ‘interesting’ where we define ‘interesting’ in part as including significant critical depth. We feel, unlike Agre’s experience in AI, this has been fairly successful in the field of HCI and that conversations we would consider interesting are now in the mainstream. Perhaps necessarily in doing so, we have modified our ideas of what critical technical practices can be and how they can be fostered since Agre’s original formulation. In this paper, we’ll reflect specifically on what it means to think of and institutionally support critical technical practice when conceived of as an interdiscipline. MOVEMENT 1: CRITICAL TECHNICAL PRACTICE AS DISCIPLINE We start with the recognition that, at least in our understanding as computer scientists encountering his work, Agre does not conceive of critical technical practice as an interdiscipline. This formulation of critical technical practice as essentially a reformative project remaining within a technical discipline may sound counterintuitive, since critical technical practice, both conceptually and in its historical instantiations, requires engagement between disciplines: technical disciplines which provide the material for working out ideas in technical form, and critically oriented disciplines such as sociology or critical theory which give traction for illuminating the blindspots of technical practice and suggesting alternatives to them. Nevertheless, Agre’s own work on agent systems demonstrated a desire to reform AI as a discipline, not to do his own work on the fringes in conversation with other Phoebe Sengers Information Science and Science & Technology Studies Cornell University sengers@cs.cornell.edu fields [2].1 As such we have taken Agrean critical technical practice not as an attempt to foster interdisciplinarity more broadly but as an intention to draw critical modes of thinking into technical disciplines as part of the problemsolving and knowledge-creation processes. In particular, we see Agre’s formulation of critical technical practice as intended to reformulate technical disciplines as simultaneously critical and technical. This would entail a shift, at least for some technical researchers, from purely technical modes of work to ones that could switch fairly seamlessly between technical and critical views on the work technology does. Certainly it requires for all practitioners an accounting of the critical aspects of technological design and analysis. “Reformulation” implies a way to think different about what is done; “reform” implies perhaps a more wholescale revision of the enterprise. Critical technical practice falls somewhere between the two. (Paul once exasperated a technical colleague by answering the all-too-common question, “What should I do differently on the basis of what you’ve told me?” with, “You might well do just the same, but perhaps for a different reason.”) Indeed, in some ways we could argue that such reformation of a technical discipline is exactly what we and our colleagues have done in HCI – i.e., took a technical discipline (if HCI counts as ‘technical, which is debatable) and added a dose of the ‘critical’ to it. This is critical technical practice broadly construed, since the exact sequence Agre relates of (1) finding technical impasses; (2) reorienting them critically; (3) spurring on to new technical work does not describe the nature of that work very well. In HCI, such movements between the critical and technical are sometimes much more deeply intermingled than that sequence would suggest, and other times practically impossible to make because of noncommunication between ‘critical’ and ‘technical’ conversations happening simultaneously within the discipline. Nevertheless, it would be fair to say that it’s become a place where ‘critical’ It is worth pausing to reflect on the consequences of Agre’s project. With respect to the question of reformulation and reform, we should note that Agre’s technical work was wildly successful within AI, but that success was to Agre’s great chagrin, since he felt that people appreciated his technical work but not the idea that he was attempting to express through it. Arguably it was this mismatch between intent and interpretation that caused him to seek other areas to explore. 1 and ‘technical’ orientations are in established conversation, in a way that may be somewhat analogous to what Agre intended. MOVEMENT 2: CRITICAL TECHNICAL PRACTICE AS INTERDISCIPLINE But more deeply, our sense is that while HCI has become a more interesting place to be, it’s not where the action is today when it comes to critical technical practice. To us, there’s a much more interesting foment going on that’s running between the disciplines, loosely intersecting with HCI, Science & Technology Studies, media studies, software studies, anthropology, design, media art practice, and communication (and probably other disciplines of which we are less aware). In part, it is driven by digitalnative scholars in more humanistic disciplines taking technology construction and the material of computing as a natural part of their practices. In part, it’s driven by technological ex-pats like ourselves who find the conversations and inspirations between the disciplines more interesting and exciting than those confined within one. Like critical technical practice, these conversations take as a basis the idea that technology is always already deeply social, and that therefore technical and critical modes of analysis benefit from being in continuous conversation. Unlike critical technical practice, these conversations are not necessarily oriented towards enrolling engineers, and are more politically conscious and intended to engage a broad public than Agre was in his instantiation as an AI researcher. Recognizing this is already happening, and already very interesting, the questions we find ourselves asking now are less intellectual than practical and institutional: how do we foster the development of that rich conversation between disciplines in such a way that is intellectually and institutionally sustainable for scholars in the area, despite significant differences in what the different disciplines involved reward as valid accomplishments? How do we maximize our effectiveness and relevance in informing future sociotechnical worlds? How do we do so in funding environments, at least in the US, that preferentially validate work seen as ‘technical’? Our initial thoughts towards spurring conversations around these questions follow. ENGINEERING AN INTERDISCIPLINE We see two key challenges in thinking about the institutional arrangements that support the work that we want to do and the communities of scholars that we want to build and engage with. The first is to retain interdisciplinarity as a value – that is, to resist the move to create disciplinary structures and arrangements, to reject the identification of canons and to remain open to new influences and new disciplinary configurations. The second is to recognise that interdisciplinarity always happens in the context of a system of disciplines. The goal in some ways is to live alongside other disciplinary traditions rather than attempting to take them over. Thus, while an initial reaction to recognizing a new emerging area may be to establish The Journal and/or The Conference of that area, we do not think this is a good idea. First, we are not all likely to agree on exactly what “this area” is, how it is constituted, and what conversations belong at the table; there is thus likely no “one-journal” solution. Second, even if we were to agree on such a constitution now, institutionalizing the area as it stands will necessarily cut off the stream of new ideas and influences that is an important element of what makes being in the conversation so exciting. Third, scholars housed in the relevant different disciplines are rewarded and get institutional support for different forms of participation. For example, to be promoted more technically housed researchers need to publish strongly peer-reviewed papers at (ideally ACM-associated) conferences, while more social-scientific or humanistic scholars tend to lack institutional support for the high registration costs involved and aren’t rewarded for the huge effort publication at that type of conferences takes. For all these reasons, it seems like a more piecemeal approach of overlapping conferences and journals may be more appropriate. As a starting point for finding publication homes and places to keep up with what’s happening, we would point to these journals: Computational Culture; First Monday; The Information Society; Information, Communication, and Society; Big Data & Society; Social Studies of Science; Science, Technology, and Human Values; Catalyst; Demonstrations; Design Issues; International Journal of Design; Fibreculture; Transformations; Ctrl-Z; New Media Philosophy; Culture Machine; Cultural Studies (we welcome additional suggestions for this list). As for conferences, the story is a little trickier. Although there are many interesting conversations happening at specific disciplinary conferences that can be interesting for those with a foot in that specific discipline (such as American Anthropological Association, Society for Social Studies of Science, or Designing Interactive Systems), at the moment we find many of the best interdisciplinary conversations happening at small one-off meetings such as Digital Labor or Algorithms & Accountability. Unfortunately, finding out about meetings such as these is hit or miss and it is not uncommon to discover after the fact a symposium one wished one had attended. One option for dealing with the bespoke nature of these meetings may be to create a central clearinghouse for notifications for such opportunities (as Agre’s Red Rock Eater was, back in the day). Still, how exactly to constitute it (mailing lists seem a little passé?) and make it a lively mechanism rather than just another voice and obligation in the contemporary cacophony is not clear. Finally, and this is another area where we do not have clear answers, we may need to think about how to create markers of value for interdisciplinary work that can be better recognized by home disciplines. For example, a computer scientist who writes sociology is not likely to become an ACM Fellow (and promotions can depend upon such things). A sociologist who writes code is likely to be similarly inscrutable in mainstream sociology. Not wanting to become a discipline does not obviate the need for the social markers of value and attainment that disciplines provide, and tend to provide preferentially for those at their centers. In addition to critical technical practices, we may also need some creative institutional practices to support one another in the development of our careers. We look forward to discussing these and other issues with the other workshop participants. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work was supported in part by the Intel Science & Technology Center for Social Computing (which has been a wonderful place to do critical technical practice as interdiscipline). REFERENCES 1. Agre, P. (1997). Computation and human experience. Cambridge University Press. 2. Agre, P. (1997). Toward a critical technical practice: Lessons learned in trying to reform AI. Bridging the Great Divide: Social Science, Technical Systems, and Cooperative Work, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 131-157.