Odum Bio:

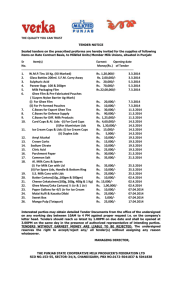

advertisement

Readings Seminar 20 Nov 2003 Turner and Dale (1998) LAJ Turner1, Monica G. and Virginia H. Dale2. (1998) Comparing large, infrequent disturbances: What have we learned? Ecosystems 1:493-496. 1 Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin, Madison 2 Environmental Sciences Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, TN This paper is the first in a series in Ecosystems (1998) 1(6) which developed from a conference at UCSanta Barbara addressing large infrequent disturbances. This issue of Ecosystems can be found at the link: http://www.springerlink.com/app/home/issue.asp?wasp=g45cjrpmqhctnvffkyvm&referrer=parent&backto =journal,36,41;linkingpublicationresults,id:101552,1 While small frequent disturbances are relatively well studies, large infrequent disturbances (LIDs) are less well understood for several reasons. Because they are large and infrequent, they are difficult to study. Predisturbance data are often minimal since the event is usually unexpected, and replication between events is difficult. Where several LID events have been studies, the data and methods are often inconsistent e.g. vegetation data were taken differently, the spatial pattern of the disturbance was quantified differently, etc. However, the papers in this series attempt to synthesize what is known about LIDs. Because disturbance ranges over a continuum of size and severity it can be difficult to precisely define LIDs. However, the authors give two ways to define LIDs. Statistically, an LID may be defined as having spatial extent, severity, or duration beyond two standard deviations from the mean. Context must be considered with this definition. For example, what may be extreme in one season may fall within two standard deviations during another part of the year. LIDs may also be defined relative to human perception or to the organisms affected by the event. The authors give the example of Mount St. Helens, which may not have been extreme on a geologic scale, but to the humans and organisms in the area, the eruption would be considered large and infrequent. Likewise, the lifespan and dispersal ability of organisms should be considered when defining the size or duration of a disturbance as large or infrequent. Several other aspects of LIDs to consider: LIDs do not necessarily have a uniform effect across the entire spatial extent; the pattern of disturbance may be complex. LIDs can serve as catalysts to change the trajectory of succession in unexpected ways. The compounding of human and natural disturbance can have multiplicative effects (e.g. the effects of watershed alteration on natural flood cycles). LIDs can have lasting effects on both biotic and abiotic components of a system. Abiotic components may include structural changes such as lava flows, land slides, or stream redirection. Biotic components may include standing or fallen dead trees, seed bank, remaining vegetation, etc. Readings Seminar 20 Nov 2003 Turner and Dale (1998) LAJ Monica G. Turner: http://www.wisc.edu/zoology/faculty/fac/Tur/Tur.html Despite being in the zool dept, M. Turner is also involved with much research involving plants, especially characterizing landscape scale spatial patterns and effects of disturbance, including fires in Yellowstone, land-use change in Wisconsin, and effects of land-use on vascular plants in the S. Appl of NC! Virginia H. Dale: http://www.esd.ornl.gov/people/dale/dale.html Also Adjunct Prof at UT-Knoxville, Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. From website: Dr. Virginia H. Dale’s primary research interests are in environmental decision making, forest succession, land-use change, landscape ecology, and ecological modeling. She has worked on developing tools for resource management, vegetation recovery subsequent to disturbances; effects of air pollution and climate change on forests; tropical deforestation; and integrating socioeconomic and ecological models of land-use change. She has published over 140 scientific articles and edited 6 books.