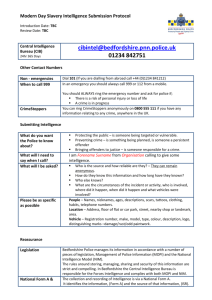

1) - Email

Abstract

Policy as regards a European database to fight organised crime needs to distinguish between criminal records databases and intelligence databases. The issues involved are different. As will be argued later: prosecutors need a case tracking database; employers need a convictions database for vetting purposes; judges need a convictions database for sentencing purposes; but police officers need databases for convictions, for intelligence and to store material on a particular complex investigation or series of interlinked investigations. The issues involved in setting up and using each overlap but are not identical.

Databases should not be seen as a route around problems arising from differences between national jurisdictions. The legal problems need to be identified and overcome as a prerequisite to setting up a database. Cyberspace is imaginary, not extra-jurisdictional

Questionnaire

1) Does your country have a database for investigations? Is it central or regional? Do these databases include exclusively criminal investigations or do they also include administrative/other investigations? What is their legal basis (statutory or other)?

Please analyse and attach the introducing legal texts as amended (in English or the original language of publication).

Background

The UK has a number of different databases, the legal basis of which is in need of clarification. The Bichard Enquiry into the Soham murders has recently reported and made a number of recommendations which will affect the whole system of data recording within the criminal justice system.

The Police and Crown Prosecution Services are organised into 43 areas in England and

Wales. There are 8 areas in Scotland, where the prosecuting authority is called the Crown

Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, and there is a single area covering Northern Ireland.

Scotland has a separate legal system to England and Wales. Each of these police and prosecution areas has at least one local database as well as access to records on the Police

National Computer [PNC2].

Although policing in the UK is traditionally locally organised, there has been a National

Crime Squad [NCS] since 1998, there is also a National Criminal Intelligence Service

[NCIS] and there is shortly to be a Serious Organised Crime Agency [SOCA] at national level. [see Consultation document “One Step ahead” Cm6167 http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/docs3/wp_organised_crime.pdf

]

1

There are a number of other police organisations within the United Kingdom, in addition,

Customs and Excise play an important role with regard to duty evasion, drug smuggling and trafficking and the Immigration Service has a role to play in dealing with trafficking in human beings. Some of these functions will be taken over by SOCA.

The whole system of national databases is undergoing a process of reform. A National

Identity Register is planned to support the introduction of ID cards, the Office of National

Statistics is working on a population register, it is proposed to make the electoral register a national database, and the Department of Education is looking at plans to produce a child identifier database. In addition there are plans for increased interactivity between databases in the criminal justice system, particularly with regard to individual criminal cases.

The Government has targets for the computerisation of recording systems in all branches of the public sector and this will include Social Services, who will be introducing an

Electronic Social Care Record.

See: http://www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/InformationPolicy/InformationForSocialCare/

FrameworkDocument/FrameworkDocumentArticle/fs/en?CONTENT_ID=4073669&chk

=4CBoI2

Access to this without the consent of the client on child protection and mental health grounds is already envisaged. Given the historical relationship between police and social work, there may be conflict in this area in the future.

In addition all social care workers will be registered on a database. Social workers will be the first to be registered, followed by care workers. There will also be special procedures for workers with international qualifications. See: http://www.gscc.org.uk/

The use of databases has been reviewed by the Bichard Inquiry, following on the Soham murder case…”to assess the effectiveness of the relevant intelligence-based record keeping, the vetting practices in those forces since 1995 and information sharing with other agencies , and to report to the Home Secretary on matters of local and national relevance and make recommendations as appropriate.” The recommendations from this

Inquiry and the response to them of the Home Office are likely to produce new legislation and a different legal basis for all these matters. The Bichard Inquiry’s report is now in the public domain at: http://www.bichardinquiry.org.uk/report/ . The most important recommendation in the present context is for a national intelligence database for Police purposes.

Existing databases used by the Police

Databases for particular investigations

What do we mean by a database for investigations? For a complex stand-alone investigation, such as a murder or similar serious crime where a great deal of information

2

has to be collated and analysed quickly, the UK has HOLMES2 [Home Office Large

Major Enquiry System]. This allows a database to be created quickly from new data gathered in the course of the investigation of a serious crime or a major incident. “It identifies and plots lines of enquiry, keeps track of vital pieces of evidence and reduces paperwork. All 53 police forces are signed up to it as well as National Crime Squad,

National Crime Faculty, Ministry of Defence [MoD] police, British Transport Police

{BTP] and Royal Military police [RMP]. Several forces can work together adding information to a single Incident Room”. [PITO website] It can also be used for lowprofile crimes such as a series of burglaries where data management becomes complex.

There also exists SCAS [Serious Crime Analysis System], which is a specialised database related to murder, rape or abduction. This is to enable the rapid comparison of such crimes and the rapid identification of past cases exhibiting similar behaviour. This enables offender profiling and allows the investigating constabulary to have access to evidence previously gathered.

These two databases were the ones identified by representatives of the police during interviews as what could genuinely be called “investigative databases”.

The general system of data recording

There is a summary of the PITO statement to the Bichard Inquiry below that explains the

PNC system nationally and the local systems. There are a number of highlights not mentioned by PITO which are worth noting here:

“…the strength of PNC is that it is a national system and depends on all forces entering quality, accurate and timely data to common minimum standards” I use this quote from the July 2000 Thematic Report of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary “ On the

Record” to illustrate what will be the biggest problems of any European database.

There is also the C.A.T.C.H.E.M database at the National Criminal and Operations

Faculty. This is primarily a research facility.

There are also regional databases, such as the Drugs Misuse Databases.

There has been a national DNA database since 1995. This is managed on behalf of the police service by the Forensic Science Service. It consist of a suspect database and a crime scene database.

“The Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), as amended by the Criminal

Justice and Public Order Act 1994, provides a power to take non-intimate DNA samples from all persons suspected of, reported for, charged with, convicted of, or cautioned for, a recordable offence. A "non-intimate DNA sample" essentially comprises a mouth swab or rooted hair (other than pubic hair). A "recordable offence" is any offence for which a person is liable, on conviction, to a term of imprisonment. The legal statutes mentioned above also provide that police may take DNA samples from suspects without their

3

consent, using force where necessary, providing a Superintendent of Police has given authority, in accordance with the provisions of PACE.”

ACPO memo to House of Lords Science and Technology Committee Inquiry on DNA

Databases http://www.parliament.the-stationeryoffice.co.uk/pa/ld199900/ldselect/ldsctech/115/115we05.htm

In the course of an investigation the police may also additionally have or seek access to a number of non-police databases:

In the public sector:

National Health Service

Inland Revenue

Passport Agency

Driver Vehicle Licensing Agency

In the private sector:

British Telecommunications PLC

The mobile phone companies such as Orange, Vodaphone etc.

Legislation

The major current pieces of relevant legislation are:

Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 http://www.lawontheweb.co.uk/rehabact.htm

Amended 2002 http://www.legislation.hmso.gov.uk/si/si2002/20020441.htm

Review 2004 http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/justice/sentencing/rehabilitation/act.html

Police and Criminal Evidence Act Revised Codes of Practice 1995

[original act 1984: http://www.swarb.co.uk/acts/1984PoliceandCriminalEvidenceAct.html

]

Code a: http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/docs/pacecodea_textchanges.pdf

all codes: http://tash.gn.apc.org/pace_act.pdf

Police Act 1997 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1997/1997050.htm

Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1999/19990023.htm

[section 60 of the above removes section 69 of PACE

“evidence from computer records inadmissible unless conditions relating to proper use and operation of computer shown to be satisfied”

4

Data Protection Act 1998 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm

Human Rights Act 1998 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm

Computers Misuse Act 1990 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1990/Ukpga_19900018_en_1.htm

Freedom of Information Act 2000 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/20000036.htm

Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/20000023.htm

Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts2001/20010016.htm

para 134 inserts a new 120A into the 1997 act

Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act. 2001 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts2001/20010024.htm

Crime [International Cooperation] Act 2003 http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts2003/20030032.htm

Problem of legal basis

The Law Society’s submission to the Bichard Inquiry suggests that there is no coherent legal framework governing the use of personal data in the public sector. They argue that this has already been recognised by the government and that the recommendations of the

Cabinet Office Performance and Innovation Unit report “

Privacy and Data Sharing: the

Way Forward for Public Services

” provide an excellent starting point. This report identified a lack of awareness of how the legal framework operated and a problem with a lack of powers to share data between public bodies, even where consent has been given.

The report argued that it was possible to achieve the objective of making better use of personal data in the delivery of public services while also enhancing privacy. It did however argue that crime policy might be the area where privacy was least possible.

The Department of Constitutional affairs produced a guide to the law on data-sharing in

November 2003 http://www.dca.gov.uk/foi/sharing/toolkit/lawguide.pdf

The guidance discusses the powers of public bodies to collect use, and disclose personal information. It considers five areas of law are involved:

• the law that governs the actions of public bodies

(administrative law);

• the Human Rights Act 1998 and the European

Convention on Human Rights;

• the common law tort of breach of confidence;

• the Data Protection Act 1998; and

5

• European Union law.

The advice in the document, in summary, is that it is a matter of administrative law as to whether a public body has the power to carry out data sharing. It must then be considered whether, even though it may have the power, its exercise may be unlawful due to the operation of the Human Rights Act of 1998, the Data Protection Act or the common law tort of breach of confidence. These provisions should be interpreted with regard to the relevant principles of the ECHR and of European law.

But there are also Home Office circulars and notes of guidance which govern police use of databases. There are ACPO [Association of Chief Police Officers] Compliance

Standards governing the placing of data on PNC2 and there will be in the near future recommendations as to best practice from the Centre of Excellence at the National Crime

Faculty, Centrex, Bramshill.

A very clear statement, which is summarised in the following paragraphs, has been provided to the Bichard Inquiry by the Police Information Technology Organisation

[PITO]. This body was established as a non-departmental public body [NDPB] in 1996 under the tripartite governance of ACPO, the Association of Police Authorities [APA] and the Home Office. PITO is responsible for the provision of national Information

Technology and Communications systems to the police. “The policies and processes that govern the operational use of these ICT services are established by ACPO and monitored by the police and HMIC.”

In addition to national services provided by PITO, primarily the PNC, there are local intelligence systems devised and operated by individual constabularies. These vary greatly. PNC comprises several national police databases, including Stolen Vehicles,

Criminal Names index and wanted/Missing persons. It is a 24 hour a day, 7days a week service available to organisations approved by the ACPO IM [Information Management]

Police Security Sub-Committee [PSSC], which controls access by the police and partner agencies, including prosecution. It has existed since 1974 and has expanded over time.

The PITO report singles out as an example, the Phoenix application, which includes criminal record information and did not go on-line until May 1995.

The information on the PNC is “owned” by police forces, and each Chief Constable is a data controller under the terms of the Data Protection Act 1998 for the management of this information.

Individual forces, under HO Circular 29/95, are responsible for creating PNC records and for data input into PNC databases. Rules governing operation of all PNC services are prescribed by the PNC User Manual, which is “owned” by the Police PNC Policy and

Prioritisation Group [P4G]. This reports to the PNC Management Sub-Committee.

Weeding and deletion of records is administered by PITO and implemented directly by

PNC software in accordance with ACPO defined business rules, contained in the ACPO memo “General Rules for Criminal Record Weeding on Police Systems”. Sine 1995 rules have been incorporated in the ACPO Code of Practice for Data Protection.

6

PITO is introducing 3 further systems over the coming years:

NSPIS Custody system [National Strategy for Police Information Systems]

NSPIS Case preparation system

Violent Offender and Sex Offender Register [ViSOR]

The Custody and Case Preparation Systems are being procured by most police forces jointly and are referred to as a single system.

The Custody system is intended to assist with the administration of custody centres and ensure compliance with the requirements of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act

[PACE]. It enables automatic reporting and updating of local arrest and summons details directly onto PNC.

The Case Preparation system is designed to assist police to compile and present prosecution case files and associated evidence for presentation to other Criminal Justice

Agencies [eg Crown Prosecution Service, Magistrates Court Service and the Crown

Court Service. The outcome of any trial will automatically be reported to PNC.

Not all police forces will go along with this system. Some have already developed their own alternatives.

ViSOR will provide police and probation with a register of violent and/or registered sex offenders An interim application was in place by September 2002 and by January 2004,

38 of the 43 police forces in England and Wales were using it.

Local intelligence systems exist throughout the Cnstabularies and their CJ partners. PNC data is “hard data” based on verifiable fact. Local systems contain much more “soft data”, often based on speculation and hearsay. The National Intelligence Model is now being used to provide a framework for assessing the reliability of information sources.

Intelligence is increasingly shared between forces and with national organisations.

Regional intelligence sharing is becoming more formally organised. http://www.policereform.gov.uk/implementation/natintellmodel.html

Scottish System

The Scottish system was singled out for praise at the Bichard inquiry. They have centralised their IT systems and their intelligence database comes on-line during 2004.

For non-UK readers, it may be worth pointing out that “United Kingdom” refers to the uniting of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England in 1707. From 1603, when James VI of

Scotland became simultaneously James I of England, the same individual was King or

Queen of both countries but each had its own separate parliament and own legal tradition.

In 1707 the parliaments were merged, but Scottish legislation was a matter for a Grand

Committee of Scottish MPs within the UK Parliament. Scotland has recently regained its own Parliament, though with fewer powers that the one that sis at Westminster.

7

There are 8 police forces in Scotland. The Lord Advocate and Procurator Fiscal can give instructions to the Chief Constables on offences and prosecutions. Otherwise the Chief

Constable has sole responsibility for operations and effective and efficient use of resources. The role of the Procurator is a major distinction between Scotland on the one hand and England and Wales on the other. It also means that there is more in common between the Scottish system and Continental European systems that between “England and Wales” and other EU systems.

The major legal difference between Scotland and England and Wales is that corroboration of evidence is required for the proof of guilt. An accused cannot be convicted on the basis of a single unsupported piece of evidence. There are other differences, but this is the most important in the present instance. There is a Separate body of Scottish Law and a separate Scottish Parliament with law-making powers in a variety of areas.

The Scottish Police Information Strategy began with a feasibility study in 1993. http://www.spis.police.uk/index.html

After 1998 the process accelerated and a centralised system was put out to tender in 2000.

This included the Scottish Intelligence Database [SID]. This database will cover all

Scottish forces by Autumn 2004 and already covered three of the eight at the time of the

Bichard Inquiry. It is worth noting that the Cullen Inquiry into the shootings at Dunblane played a role in accelerating progress in a similar way to that about to be played in

England and Wales by the Bichard Inquiry.

Cullen Inquiry Report: http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/scottish/dunblane/dunblane.htm

ACPOS acted for 5 reasons:

Intelligence held on one of the 8 systems failed to comply with the legal requirements of the Human Rights and Data protection Acts

Data was a mixture of 4x4 and 5x5x5 format and therefore non-ECHR compliant

Existing systems neither met need to protect sources nor where they networked in-force, so intelligence picture fragmented

National system did not exist and intelligence exchanged via paper-based system

Development of National Intelligence Model demanded an integrated system to deliver generic products

The Scottish Criminal History System [equivalent of NCIS in England and Wales and linked to it, but the information within it is not identical, and there is a difference between a “caution” in Scotland and a “Caution” in England and Wales] already had “intelligence markers” on individual records, so that an inquirer may be informed that intelligence is held on the individual by another force. It also has “intelligence flags” so that the force holding information will know if a particular record has been accessed. It is also possible to place a “target flag” on an individual on whom a live operation is underway.

8

Full details are available in the ACPOS evidence to the Bichard Inquiry http://www.bichardinquiry.org.uk/10663/full_evidence/0089/00890002.pdf

The full statement is worth reading as it covers much of the thinking that wen into setting up an integrated system.

A quotation from this evidence is particularly pertinent:

“In an increasingly litigious society police responses have to be seen to be necessary and proportionate, particularly now that the UK has implemented ECHR in the form of the

Human Rights Act 1998.”

Legal Basis

The legal basis of ACPO and ACPOS manuals is unclear. Presumably Home Office

Notes of Guidance are based in legality on Delegated Legislation under Statutory

Instruments. The legal status of ACPO as a source of law appears to be anomalous, to say the least. ACPO members were at one time Justice of the Peace and therefore had some legal status but this has not been the case since the 1960s. Perhaps it should be so again, given the increasing quasi-judicial role played by senior police officers. Bichard reports that ACPO guidance aims to help Chief Officers achieve good practice but it is not binding on individual Forces or authorities other than by agreement. “Forces are free to introduce and implement their own policies, even where ACPO has agreed a national policy.” Forces are, however, invited to produce justification for departing from national policy.

Bichard Recommendations

Recommendations in the Bichard Report will affect many of the practices and processes of database management in the UK. The ones that are selected here are of general relevance. Others will be raised as appropriate in this report.

Bichard found there was no national information technology system in place for police intelligence in England and Wales. There is, however, one in place in Scotland. He thought the creation of one was a matter of urgency. There is debate between ACPO and the Home Secretary as to who is responsible for the absence of such a database. At present such intelligence systems as exist are held by the individual Forces and most are not directly readable or interrogatable by other Forces.

Bichard’s second recommendation is that the PLX [Police Local Cross-reference] system which flags that intelligence is held about an individual by a particular Police Force should be introduced in England and Wales by 2005. It is already in place in Scotland.

An intelligence system was planned for England and Wales in 1994, then dropped in

2000. PITO intends to “roll PLX out” over the next year as a stopgap. http://www.computerweekly.com/Article131698.htm

9

Bichard’s seventh recommendation is that the transfer of responsibility from the police to the Courts themselves for inputting Court results onto PNC should be reaffirmed and if possible accelerated. The present deadline of 2006 at least must be met and Bichard wished to see the transfer take place as early as possible. He placed responsibility for this on the Court Service and the Home Office.

Bichard also wants the quality and timeliness of PNC data input to be routinely inspected by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary.

Implicit in the Report is that the process called “weeding” should be recognised as two quite separate processes, one of which is retention, the other of which is deleting.

Bichard wants “clear guidelines in place as to what should be retained, what should be deleted and what should be available as part of a vetting procedure for employers particularly employers where work is to be done with children.”

2) Is there a database for prosecutions in your country? Is it central or regional? Do these databases include exclusively criminal prosecutions? What is their legal basis

(statutory or other)? Please analyse and attach the introducing legal texts as amended

(in English or the original language of publication).

There is at present no database for prosecutions in England and Wales. There are several projects under development including one to introduce a file-tracking system and various other initiatives to improve the use of and compatability of information technology systems.

The Case Preparation System mentioned above by PITO will be the one closest to what I assume is meant here by a database for prosecutions. There is no database owned by the

Crown Prosecution Service, yet, but there is a project entitled “Compass” under development, and one called “J-track”. As mentioned in the answer to question 1 above, the Crown Prosecution Service is one of the agencies allowed access to PNC2 and it is envisaged that this will be the case with the new databases and applications that are coming on-line in the next few years.

The submission of the Crown Prosecution Service to the Bichard Inquiry states that before 2003, there were at most electronic card index systems, accessible mainly locally.

A Casework Management System was introduced in 2003, principally designed to monitor the progress of individual cases. It is “neither an intelligence system nor a substitute Criminal Records Bureau”. Initial case files delivered by the police are mostly retained on paper. Many areas operate joint police-CPS units with a single file system.

Retention tends to be by the police as they have the right to retain for longer periods due to their different responsibilities.

10

Cases are divided into categories A,B,C,D,E and F. Category A consists of those that are in the long term public interest are kept for 30 years then transferred to the national archive at Kew. Of the other categories, D is treated differently. B,C, E and F are kept until the end of the sentence. Category D is managed at local level as this sort of case tends to be required at short notice.

All policies are at present under review partly because of the Soham case, partly because of the incipient introduction of electronic filing and partly because of the expectation of closer working with the police.

The CPS Records Management Manual is available both on the Bichard Inquiry website and on the CPS Website. http://www.bichardinquiry.org.uk/10663/full_evidence/0091/00910125.pdf

Scotland

The Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service is under more pressure than most prosecutors because of the 110 day rule. Once a charges is made, the case has to be brought to court within 110 days or dropped.

There is a working group composed of members of the Scottish executive Justice

Department and the main Criminal Justice partners working on improvement of the statistical and management information information available on the criminal justice system in Scotland. The current thinking is that a data warehouse approach will be the most effective.

The Future Office System is being introduced by the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal to enable electronic filing, recording and case tracking. It sounds like a database for prosecutions. There is an initiative for electronic courts COPFS/SCS and an ISCJIS[

Integration of Scottish Criminal Justice Information Systems] scheme for electronic documentation production. http://www.crownoffice.gov.uk/publications/Crown%20Office%20Strategy.pdf

www.crownoffice.gov.uk/publications/ DASPID1finalrevMar03.doc [this link does not work for some reason and the Google.html search link has to be used: http://66.102.11.104/search?q=cache:jTykM62MqbkJ:www.crownoffice.gov.uk/publicati ons/DASPID1finalrevMar03.doc+Electronic+Courts+Scotland&hl=en

3) Which national, EU or international authorities have access to the databases? If such databases do not exist, who has access to information on investigations and prosecutions?

There is no direct access for EU or international authorities to the databases. Access takes place through NCIS and the Sirene Bureau. For international authorities access would be routed through the Interpol Bureau which is in the same office as the Sirene

Bureau. Requests are made under articles 39, 40 and 46 of the Schengen Convention.

11

Requests come through the Sirene Bureau which is effectively NCIS. Article 39 requests will be able to come “live” through the Schengen Information System [SIS] when that comes onstream in 2005.

Prosecutors and examining magistrates can make a request via the Home Office under the

Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters Convention. In practice the information can be obtained much more quickly if a Prosecutor asks a Police Officer to make an Interpol request and this would then go directly to NCIS.

It is an English view that Prosecutors only need a case progression database. They have no real need for access to an investigative database. This may not be shared in other EU countries.

Since 9/11, a number of working relationships have developed, particularly with regard to terrorism, which are difficult to document for reasons of operational security.

Increasingly PITO works with the Home Office branch, the CJIT [Criminal Justice IT

Organisation] which is bringing it into contact with other agencies: courts, prison, probation CPS and it is also beginning to work with health, social services and the emergency services [evidence to Bichard Inquiry by Mr. Webb 23 rd

March 2004 am].

Child protection issues have led to the requirement for all these agencies to examine how best to exchange information. The Bichard Inquiry has addressed these and related issues in its final Report.

Evidence from abroad

The Crime [International Cooperation] Act 2003 section 81 amends the Data Protection

Act 1998 and inserts a new section 54A giving the Commissioner powers to inspect data in the Europol, Customs and Schengen Information Systems and to inspect test and operate equipment used for the purpose of data processing…is this just from a terminal in

UK or is he seriously supposed to be able to do this at the place where the server is based? And do we give reciprocal rights to similar officers in other member States?

Articles 13-19 of the same act deal with requests for evidence from abroad…but do not refer to databases or information from the same, yet the process of obtaining the evidence will clearly involve the use by the territorial authority in the UK of database interrogation in the first instance…

Section 14 gives the territorial authority power to obtain evidence where a request is made, if the authority is satisfied:

“a) that an offence under the law of the country in question has been committed or that there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that such an offence has been committed, and

(b) that proceedings in respect of the offence have been instituted in that country or that an investigation into the offence is being carried on there.”

12

This covers administrative proceedings as well as criminal proceedings.

But this does appear to be cover obtaining evidence, not simply information.

This raises a related issue, that of datasharing in the public sector. A debate has been initiated by the recommendations of the Cabinet Office Performance and Innovation Unit report “

Privacy and Data Sharing: the Way Forward for Public Services

”. Available at: http://www.number-10.gov.uk/su/privacy/pdf.htm

The response from Liberty is available at: http://www.liberty-humanrights.org.uk/resources/policy-papers/policy-papers-2002/pdf-documents/jul-2002privacy-data-sharing.pdf

And the Department for Constitutional Affairs has provided an update as of November

2003 at: http://www.dca.gov.uk/majrep/datasharing/update.htm

The intention is to bring forward legislation on data sharing. The working group has rejected the idea of a general power to share data with consent and is examining the idea of legislation to create a general power to set up data sharing gateways via secondary legislation.

The Home Office has produced a model protocol for data-sharing available at: http://www.crimereduction.gov.uk/infosharing21-00.htm

and a Government data standards catalogue is available at: http://www.govtalk.gov.uk/schemasstandards/eservices.asp

There is a standard for information security management: ISO 17799/BS7799

4) At which procedural stage are data introduced to the database (for example, at police/law enforcement investigation, launch of formal prosecution, or trial)?

This depends on which database an entry is being made.

The individual Police Forces are responsible for entering data onto the PNC Phoenix database and each has direct access to the system. Normally Phoenix includes an individual’s name, known aliases, sex, age, height and distinguishing features.

At present the Police are still responsible for putting Court results onto the PNC. The original intention was that arrests and summonses would be placed on the PNC at the time they were made. Bichard found, however, that with the exception of prevention of terrorism legislation the first record on the PNC is usually when a person is charged or cautioned. The Court Service will take over responsibility for inputting Court results in

2006. Bichard would like to see that process accelerated.

For the new intelligence database that Bichard envisages, his prime concern was with the recording of acquittals and cases not proceeded with, so this data would be entered at the same point.

13

Data for proactive investigation would be another matter entirely and where this happens at present the relevant information is not at present in the public domain.

5) At which procedural stage are data erased for the databases?

Repeating information supplied in answer to question 1, the information on the PNC is

“owned” by individual police forces, and each Chief Constable is a data controller under the terms of the Data Protection Act 1998 for the management of this information.

Individual forces, under HO Circular 29/95, are responsible for creating PNC records and for data input into PNC databases. Rules governing operation of all PNC services are prescribed by the PNC User Manual, which is “owned” by the Police PNC Policy and

Prioritisation Group [P4G]. This reports to the PNC Management Sub-Committee.

Weeding and deletion of records is administered by PITO and implemented directly by

PNC software in accordance with ACPO defined business rules, contained in the ACPO memo “General Rules for Criminal Record Weeding on Police Systems”. Sine 1995 rules have been incorporated in the ACPO Code of Practice for Data Protection.

Increasingly there is a debate about records, particularly as regards fingerprints and DNA.

With US demand for biometric data and proposals for a National Identity Card, there are proposals that some forms of personal data will be kept permanently. Paedophile databases are also permanent so that enquiries can be made where individuals are applying for work with children and sexual offenders excluded from this area.

There has also been a disagreement between ACPO and the Information Commissioner which is documented in the submissions to the Bichard Inquiry arising from individual complaints about data kept by the police and passed on to employers. This will be dealt with in greater detail in response to Q 22.

Bichard found the following and this point is central to his Inquiry, as it concerns the failure to identify Huntley as having a record of accusations against him with regard to underage sex.

[The following is paraphrased from the Report]: there is a lack of clear national guidance about information management in the sense of the way information is recorded, reviewed, retained or deleted. There is reference to record creation in the ACPO Code of Practice on data protection of 2002 which replaced the 1995 Code. This does little more than summarise the importance of information being relevant, accurate and up-to-date and is more or less taken from the Data Protection

Act. There is a “pressing need for clearer guidance in this area” [Para 3.67].

The ACPO Code did provide eight pages of guidance for Forces in terms of retaining data in compliance with principal 6 of the Data Protection Act of 1984. This stressed that

14

no absolute rules could be laid down about how long particular items of personal data could or should be retained. A series of questions were given as a test:

What purpose does the data now serve?

Is the data still relevant to the registered purposes?

How useful is the information likely to be in future?

The original guidance also advised that it might be necessary to consult the officer responsible for making the initial record and the 1995 guidance recommended that all the above should be applied to manual records despite the fact that the legal requirement for this came later. [ Para 3.70]

It also suggested an automatic review should be built into systems. This, Bichard stressed, was a review not automatic deletion. [Para 3.71].

16 th

June 1995 a policy document was circulated by ACPO General Rules for Criminal

Record weeding on Police Computer Systems.

Conviction for a reportable offence, retention for twenty years. Exceptions where the conviction was for an offence against a child, or young persons, in this case the record was to be kept until the offender was seventy years old subject to a minimum twenty year retention period.

In case of a rape conviction record to be retained for the life of the offender.

Records of cautions assuming there were no other convictions or further cautions, retained for five years.

Records of disposal other than conviction, caution, acquittal, discontinuance and not guilty bind over were to be retained for the same period as set out for convictions, ie twenty years, but acquittals and “discontinued cases without caution” not normally to be retained beyond a forty-two day period from the disposals notification date.

However this general rule is subject to exceptions when the record “should be considered for retention”. These included

Acquittal for an offence of unlawful sexual intercourse by a male with a female under sixteen. In such a case the record should be deleted when the male’s age reached twenty-five subject to no other offences being recorded.

If there was an acquittal or discontinuance because of a lack of corroboration or an allegation of consent in a case in which a sexual offence was alleged the record could be retained for five years on the authorisation of an officer not below the rank of Superintendent and the record would be reviewed at the end of that period.

15

The [ACPO] Crime Committee policy gave guidance to the officer making that decision and laid down three criteria as necessary preconditions for retention: (a) the case’s circumstances would give cause for concern if the subject was to apply for employment in a post that involved substantial access to vulnerable persons;

(b) the facts of the case showed that the subject’s involvement was based on information that was high quality and could be graded A1 when the 4x4 reliability test was applied; (c) the decision to retain the information could be defended on public interest grounds.

[4x4 test: a subjective alpha/numerical intelligence grading system used by most police forces to determine the reliability of a piece of information (on a scale of A, B,

C and X) and the reliability of the source of the intelligence (on a scale of 1–4).

Therefore, ‘A1’ means the intelligence source is highly credible and the intelligence is of a high standard. Glossary, Bichard Report

Now succeeded by 5x5x5 test incorporating the two factors above but including a judgement about who can have access to that intelligence (on a scale of 1 to 5).]

In September 1999 new rules from the ACPO Crime Committee changed the general period of retention from twenty years to ten years. There were exceptions where the conviction was for an offence involving a child or a young person as victims. In such a case the record was to be retained either until the subject died or until the subject reached

100 years of age. Records of disposals were to be retained for ten years for most offences. The 1999 weeding rules removed the reference to AS1 intelligence.

In October 2002 the ACPO Code of Practice on data protection was revised. Again the foreword from the Information Commissioner stressed that any specified retention period could only be a benchmark. The Information Commissioner would be obliged to examine on its individual merits any case referred to her. The 2002 ACPO Code did not make any changes of significance for the Bichard Enquiry. It dealt with criminal intelligence records and recommended that all intelligence reports should be regularly reviewed and considered for deletion subject to a maximum review period of 12 months.

Each of the 43 Forces produced its own set of local guidance and directions to give effect to ACPO and others national guidance. Content varied widely. Humberside, for example, followed a very different approach to that contained in the national guidance.

HMIC admitted that it had not carried out inspections of data protection weeding and that it would be doing so in future.

Stop Press:

On 22 nd July 2004 in a landmark judgement the House of Lords decided that the Police can keep DNA samples even where criminal investigations have been dropped. The argument had been made that the South Yorkshire Police, in keeping DNA samples after the two cases were dropped, were contravening either the individual’s right to a private life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights or the right not to be

16

discriminated against under Article 14 of the same Convention. Lord Brown argued that the cause of Human Rights would be better served by expanding Police databases rather than deleting records. He said the only logical reason to objecting to samples being kept by the Police was that it would make it easier for Authorities to arrest someone if they ever offended in future. Lord Steyn said that Police should be able to take advantage of modern technology which “enables the guilty to be detected and the innocent to be rapidly eliminated from enquiries.” The decision affects both DNA and fingerprint records. It is likely to be taken to the European Court of Human Rights.

6) What is the purpose of the databases as described in their founding instruments?

What is their use in practice?

The databases exist for a number of purposes but the PNC was originally established to improve record-keeping on criminals. PNC2 was established to improve exchange of information between constabularies.

It is the use of these databases for employment vetting that has caused most conflict in practice. Bichard has proposed that a separate agency is made responsible for deciding what details to release to employers so that the police can be removed from the conflicts involved.

7) Is there collaboration with foreign authorities for the acquisition of data on investigations and prosecutions (please refer to Europol/Eurojust)? Which authorities have access to this data?

The UK cooperates with foreign authorities via the Sirene Bureau, the Europol Bureau and the Interpol Bureau, all now in NCIS. Michael Kennedy represents us on Eurojust and is also President of Eurojust.

There is also collaboration via Mutual Legal Assistance or through Liaison Officers in the European Embassies or through, in the case of terrorism, the Terrorism Liaison

Officers who go via Special Branch in the UK and this is a completely separate system.

For cases of fraud and for the Serious Fraud Office, on the whole contacts are via the

NCIS but lawyers from the Serious Fraud Office can write directly to their counterparts in other jurisdictions. There is thus a legal route and an intelligence route which is via

NCIS. There is not necessarily an absolute demarcation between these two routes, they represent tendencies towards a particular direction.

17

The UK has a problem with Europol in terms of second party disclosure.

Comment repeated from answer to question 3

There is no direct access for EU or international authorities to existing databases. Access takes place through NCIS and the Sirene Bureau. For international authorities access would be routed through the Interpol Bureau which is in the same office as the Sirene

Bureau. Requests are made under articles 39, 40 and 46 of the Schengen Convention.

Requests come through the Sirene Bureau which is effectively NCIS. Article 39 requests will be able to come live through the SIS when that comes onstream in 2005.

Prosecutors and examining magistrates can make a request under the Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters Convention and this would go to the Home Office. In practice the information can be obtained much more quickly if a Prosecutor asks a Police Officer to make an Interpol request and this would then go directly to NCIS.

The feeling of the senior English Police Officers interviewed was that Prosecutors only need a case progression database. They have no real need for access to an investigative database.

If the question is about possible routes forward, then a TETRA-style network might be developed to link networks such that the simple question could be answered as to whether an investigation was under way or a prosecution in process against a particular named individual.

8) What provision is made in your national laws for data sharing between public bodies? What are the relevant restrictions?

PNC is a 24 hour a day, 7days a week service available to organisations approved by the

ACPO IM [Information Management] Police Security Sub-Committee [PSSC], which controls access by the police and partner agencies, including prosecution.

General comment on data-sharing law repeated from answer to Q.1.

The Law Society’s submission to the Bichard Inquiry suggests that there is no coherent legal framework governing the use of personal data in the public sector. They argue that this has already been recognised by the government and that the recommendations of the

Cabinet Office Performance and Innovation Unit report “

Privacy and Data Sharing: the

Way Forward for Public Services ” provide an excellent starting point. This report identified a lack of awareness of how the legal framework operated and a problem with a lack of powers to share data between public bodies, even where consent has been given.

The report argued that it was possible to achieve the objective of making better use of personal data in the delivery of public services while also enhancing privacy. It did however argue that crime policy might be the area where privacy was least possible.

18

The Department of Constitutional Affairs produced a guide to the law on data-sharing in

November 2003 http://www.dca.gov.uk/foi/sharing/toolkit/lawguide.pdf

The guidance discusses the powers of public bodies to collect use, and disclose personal information. It considers five areas of law are involved:

• the law that governs the actions of public bodies

(administrative law);

• the Human Rights Act 1998 and the European

Convention on Human Rights;

• the common law tort of breach of confidence;

• the Data Protection Act 1998; and

• European Union law.

The advice in the document, in summary, is that it is a matter of administrative law as to whether a public body has the power to carry out data sharing. It must then be considered whether, even though it may have the power, its exercise may be unlawful due to the operation of the Human Rights Act of 1998, the Data Protection Act or the common law tort of breach of confidence. These provisions should be interpreted with regard to the relevant principles of the ECHR and of European law.

9) Are there national general principles of law and privacy laws which prohibit either the creation of national databases on investigations and prosecutions or the use of such data? Please describe and attach these laws.

There are no UK laws prohibiting the creation of a database. Such databases already exist in the UK. As noted in the answer to the previous question it is data-sharing that raises legal problems.

10) Is there an exemption to these laws, for example on the basis of the general “public interest” to combat crime? Could such an exemption supersede national privacy laws?

National Security

Is there really a public interest exemption or is this something drummed up by newspaper editors to protect themselves against a privacy law? [answer yes it’s to do with data retention. Discussed in Bichard]

11) In view of measure 12 of the mutual recognition programme (OJ C 12, 15.1.2001, p.

10), would linking national databases be an effective weapon against transnational

19

crime or would an EU database on investigations and prosecutions from all EU

Member States be preferable? What added value for your national authorities do you see in the setting up of a EU judicial database as foreseen in Eurojust and, if there are any, what would be the current legal difficulties to be upheld in your country for the connection to such a data bank?

If there were to be an EU judicial database, what would it contain? There is a feeling in the UK that a comparative law database is increasingly needed. If such a database included judicial decisions this would be especially useful given the move of the EU to framework decisions which produces 25 different national implementations which in turn produces a need to know what the differences are between the different implementations.

A database that provided that information would be extremely useful.

Measure 12 asks how best the competent authorities in the European Union should be informed of investigations or prosecutions outstanding in respect of a given individual, covering, in particular, the categories of offence potentially concerned and the stage of proceedings at which the information process should start. It should also consider which of the following would be the best method: (a) to facilitate bilateral information exchanges; (b) to network national criminal records offices; or (c) to establish a genuine

European central criminal records office.

The grammar of the measure is odd. Presumably, it means, how can the competent authorities find out if a given individual has an investigation or prosecution outstanding against them? Or does it imply that a passport or identity card check should immediately and automatically throw up this information as a result of a barcode scan that would link into a closed and secure network in some way.

Where an investigation of a serious crime is underway, surely the last thing that an investigator would want is that a routine check of a person’s documentation led to behaviour on the part of a uniformed police officer that informed the person being investigated that such an investigation was under way? Investigating organised crime involves surveillance and identifying an individual’s contacts without alerting them to the fact that they are under investigation.

If the intention is to apprehend an absconder, then that is a totally different matter.

Is, however, what is required a system that throws up information on investigations or prosecutions underway in other Member States against an individual into whom an investigation has been opened or whose name has come up in the course of an investigation? If so, the existing Sirene Bureaux is the appropriate system upon which to build, but with an improvement in accessibility for investigators at lower levels than the national as long as it has provision to warn other investigators that access has been made, so that on-going investigations are not compromised. There will need to be a body and a

20

procedure to deal with such conflicts as to which investigation and which country has priority and this will almost certainly mean a role here for Eurojust and for Europol.

Presumably what we are looking at is something that would benefit a hands-on investigator. And the question that needs to be answered is what we would need above and beyond the SIS (Schengen Information System). The Europol database is a good one but it is not supplied with sufficient data and it can only be accessed via national units.

The existing databases need a greater quantity of data supplied and they need the possibility of wider access to improve the possibilities for a hands-on investigator.

Access is the fundamental problem, as opposed to the architecture of the databases. The level at which access can be made needs to be determined. As mentioned above, there also need to be dispute resolution procedures in place. The greater the access, the more likely it is that investigations will conflict, and the greater the likelihood of security being breached.

The problem for a hands-on investigator is not so much access to data on prosecutions and convictions, but to data on intelligence. For this reason a European version of the UK

National Intelligence model is required together with a 5x5x5 test of reliability. The legal problems of empowering direct access to such data on the part of an investigator from another country are the ones that need to be addressed, rather than data on convictions.

Often what is required is to know what an individual is suspected of in order to know what to look for in their relations with other individuals and organisations. The creation of a UK intelligence database needs to parallel those similar databases that already exist in other member States. The interviewees thought that the data protection issues here would be fairly difficult to overcome.

The prevailing IT doctrine in the UK is, however, changing as the following quote shows:

“I think today we are looking at a far more information centric architecture which provides information as the entity which is common across the entire environment, whereas in the days of NSPIS, it was a far more systems-based structure where people had individual systems and they would talk to each other, whereas now we are looking at far more commonality of information, perhaps in central databases or centralised

databases, where the information is shared.” Mr. Webb of PITO Bichard Inquiry March

23 rd

2004

The EU needs to go through the intermediate step of a common data recording strategy.

When all Member States record the same data in the same format, it will become possible to move to central databases.

Most so-called transnational crime actually consists of regional groups trading with other regional groups. The Europol Joint Investigative Team with a case specific approach seems adequate enough and databases for individual investigations are more rational.

Although there is now software available in the US, apparently, that can search databases much more quickly than has previously been possible, the principle of Occam’s razor remains an excellent one.

21

An EU database will only be efficient if there is an obligation to notify which is then followed through. Irene, OLAF’s database has been plagued by a failure to notify of offences of fraud. Multiply that by 50 other major offences and there will be lots of gleaming machinery and very little data. Tupman and Tupman discussed the EU database strategy in 1999. The same shortcomings are still apparent:

The following thoughts from the present author, written in 1999 have been updated slightly to take account of changing names of organisations.

“The Database Strategy

In default of a European FBI, all attempts at cross-border police organisation since 1985 have centred on the creation of a networked computer database. A number of such crossborder databases and database-related communication systems have now been established as necessary prerequisites for risk-assessment together with offender and offence profiling. Their advantages are:

offender profiling is vital for identifying individuals and organisations who commit relevant types of offence - fraud, smuggling, trade in people;

offence profiling ensures that investigators are up-to-date with the modus operandi of the various offences being committed and with the organisational structures required to commit them;

risk-assessment enables proper targeting of scarce resources, both for prevention and successful investigation;

information technology enables rapid exchange of relevant intelligence between investigative organisations across frontiers and removes bureaucratic obstacles with regard to provision of evidence. At the same time officers remain accountable to existing command structures.

All cross-national database schemes have had problems achieving their original goals.

The major problems have been:

compatibility between EU Member States' software and hardware;

judicial acceptability of on-screen communication in place of paper;

data-protection and privacy;

analytical software for profiling;

consistency of reporting of offences by individual countries and organisations.

The Schengen Information System (SIS) has been transformed into a man-machine interface by the SIRENE bureaux. The former’s original anti-immigration aspect has recently been transferred to the proposed database Eurodac .

The European Commission’s own investigative organisation, formerly UCLAF, now

OLAF, assists Member States to focus on high risk areas by providing information resulting from an analysis of information on its databases: - pre-IRENE (IRégularities,

ENquêtes et Exploitation), for cases of fraud under investigation and IRENE, for cases successfully investigated. These were combined to create IRENE 95, another step

22

towards upgrading the system from an electronic filing cabinet to a full-scale independent knowledge-based system that can identify and analyse risk factors. IRENE has had many problems in gestation, but in late 1999 included over 20,000 cases.

The other major relevant databases are DAF (Database Anti-Fraud), SCENT (System

Customs ENforcement Network), and CIS (Customs Information System). There are now 323 SCENT/CIS terminals installed at airports and administrative headquarters.

They may be used to record and to access data on both Community and non-Community matters. With regard to CIS, European Union Member States have adopted a convention on the use of information systems in the customs field. Agreement has also been reached on the provisional application of this convention between some of the Member States.

The convention itself has not yet been ratified, so the central database cannot yet be created. Without further research, it is impossible to say whether there is deliberate obstruction on the part of some Member States, or if some have a technology problem.

On 26 July 1995, under article K3 of the Treaty of Maastricht, a Convention was signed on the use of information technology for customs purposes. It provided a legal basis for including in a database information to combat drug-trafficking. This database has been set up. In addition, the system for registration of goods in transit across the EU is being computerised, in cooperation with EFTA: ‘Although it is obvious that computerisation will not totally wipe out fraud, it is safe to assume that the cost of this project will soon be recouped’.

This view is belied by the development of every computer system. It is not safe to assume costs will be recouped. It is safer to assume that the system will not do what the client originally thought it would. What it does may be useful but will not be as per specification. The databases so far established in the European Union have been good at recording data, but poor at analysis, and have run into data-protection and judicial supervision problems that have reduced them to electronic filing-systems of limited utility as investigative tools. Nevertheless they continue to proliferate. The Europol

Convention is 75 per cent concerned with database matters. It is time for serious analysis of investigator use of databases in order to establish how successful they have been in achieving their original goals, to identify good practice and to establish real costs. Above all, a project needs to be established to examine and overcome the legal and technological problems of moving from a primitive man-machine interface to intelligent, analysiscapable software.

An intelligence- and database-oriented approach is unlikely to be successful if information is slow to reach database managers because of bureaucratic delay and complexity. To by-pass obstacles, UCLAF proposed the installation of ‘an experimental freephone service to allow European citizens to provide information on fraud in confidence directly to the Commission’. The freephone number received over 4,000 calls in the first 12 months of its operation from November 1995. Around 200 of these led to further investigations and subsequent formal enquiries involved amounts of over 30 million ECUs . It is tempting to wonder what the impact would be of a European version of Crimewatch [It would be a big step forward from the Eurovision Song Contest!] [I’m copyrighting this idea!]

23

Equally important, if databases are to provide a true picture, is the issue of notification.

A targeted strategy demands reliable, up-to-date information. A Commission proposal to improve both the level of detail and frequency of submission of Member States’ reports of fraud and irregularities was adopted during 1996. The intriguing question is how long it can be before banks and financial institutions are also placed under legal obligation to report fraud to a central database run by a Financial Intelligence Unit. The impact of a database-led strategy will be affected by the priorities of individual countries.

Investigative priority will be determined by the perceived scale of the problem and this is normally measured on a purely financial basis. Article 209a of the Treaty of Maastricht establishes ‘the assimilation principle’, whereby Member States shall take the same measures to counter fraud affecting the Community as they take to counter fraud affecting themselves. In the UK this may be counter-productive - officers from the

Serious Fraud Office have told the author privately that they do not investigate frauds below £5million. This is because of the immense costs of prosecution. Presumably, local fraud squads, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries inspectors and Inland

Revenue officials operate to different guidelines. Recognising this problem, the

Convention on the Protection of the European Communities Financial Interests of 26 July

1995 instructs Member States to define serious fraud as involving a minimum amount that cannot be set at less than 50,000 ECUs. Legislators may define an offence as serious by using financial criteria, but investigative priority cannot be guaranteed where there is already a heavy domestic case-load that is being prioritised on the basis of higher monetary value.

As long as the policing of cross-border crime is hamstrung by governments’ reluctance to set up a permanent cross-border police organisation, idiotically complex sets of regulations will continue to be passed. The Treaty empowered Europol to set up joint investigative teams for individual operations. Customs organisations can already do this, so there is a precedent and this may produce a more effective halfway house.

The Customs network, finance ministry-driven and concentrating on drug smuggling and revenue invasion, has been the most successful integrator of information technology and joint investigation teams. I commented in 1999 that Europol had too many potential responsibilities and suffers from in-fighting between the Ministries of the Interior and

Justice, which was then preventing the K4 Commission [ now the Title VI Commission] from developing into a successful driver of policy. The Schengen system has made progress but had to move away from its original, information technology-driven, vision.

Europol and OLAF need to be coordinated. OLAF fortunate in its freedom from the multi-national decision-making process and single-crime oriented, is the only supranational body capable of driving cross-border investigative policy and practice forward. The organised crime groups it investigates are involved in many other types of crime outside its competence. It will of necessity exceed any brief it is given. While this should be welcomed if it increases the effectiveness of the battle against organised crime, it will inevitably be portrayed as part of the battle for sovereignty between the

Commission and certain Member States.” (Tupman and Tupman Policing in Europe pp

91-94)

24

12) Could the EU establish a database for investigations and prosecutions that includes relevant data on EU citizens, supervised by a judicial/quasi judicial authority be acceptable to your national legal orders? What problems, if any, would you foresee and how could they be resolved?

There would probably be less legal problems for the UK than for many other member states of the European Union. The UK databases would have to comply with data protection law, the European Convention on Human Rights, and Court decisions with regard to privacy.

The problems will primarily be political. Daily Telegraph will go berserk, followed by the Mail, the Times and probably the Express! UK would opt out. Databases for paedophiles and sex offenders are easily saleable, but cigarette and alcohol duty evaders are seen as legitimate. The Sun newspaper has even run a campaign supporting them.

There is a frightening lack of recognition in all the European Commission documents on this question of the existence of a European democratic deficit and of a need for any aspect of policing to concern itself with legitimacy. The European Parliament may appear to be obstructionist to the technocrats that are proposing these solutions, but there is a danger of widening the gap between the public and central institutions unless this issue is borne in mind. Databases are a useful tool, but if the public isn’t coming forward and reporting crime, there will not be any data. Equally, there will not be any witnesses giving evidence when the court proceedings begin. So there will be no convictions.

13) Could the EU database supply data to be accepted and used as indirect information or evidence before your national courts, or would your national laws limit its use to the support of investigations and prosecutions via the provision of soft intelligence?

It is unlikely that data from an EU database would be accepted as evidence. The UK

Courts would want to go back to the source of the information and be able to cross examine the witness who provided it. As regards the provision of limiting it to the provision of soft intelligence, the answer is almost certainly ‘yes’.

The UK government in the Organised Crime White Paper March 2004 strongly supports the creation of an EU intelligence model on the lines of the existing UK National

Intelligence Model and supports the second generation of the Schengen Information

System.

See answer to Q 11

Polics and politicians in the UK would be interested in the creation of a European criminal intelligence model. This would need to be created by the European Police

25

Chiefs Task Force. It would then be necessary to create appropriate hardware and software to provide the analytical capability. All this would have to be in a framework that would define intelligence in such a way that it would not terrify East Europeans who remember the meaning of intelligence as used by their former communist rulers.

14) Which crimes could be included in the EU database for investigations and prosecutions? Could it extend past the limited crimes included in the

Europol/Eurojust mandate?

You need to start by deciding what the requirements are for a successful investigation of organised crime, then build your database so that it can supply useful information. Unless it is intended that the database will consist of a list of individuals convicted for their involvement in organised crime and the cases in which they were prosecuted plus your soft intelligence on them. Start with the individuals not the crime. But to do that you need to have legislation in place legalising proactive investigation and a procedure for legalising and legitimising data entry.

In terms of United Kingdom law any crime could be included on a database. The decision would be a business or economic decision rather than a legal decision.

22 nd

July 2004 House of Lords decision that the Police can keep DNA samples even though criminal investigations have been dropped. The argument had been made that the

South Yorkshire Police in keeping DNA samples after the two cases were dropped were contravening either the individual’s right to a private life under Article 8 of the European

Convention on Human Rights or the right not to be discriminated against under Article 14 of the same Convention. Lord Brown argued that the cause of Human Rights would be better served by expanding Police databases rather than deleting records. He said the only logical reason to objecting to samples being kept by the Police was that it would make it easier for Authorities to arrest someone if they ever offended in future. Lord

Steyn said that Police should be able to take advantage of modern technology which

“enables the guilty to be detected and the innocent to be rapidly eliminated from enquiries.” The decision affects both DNA and fingerprint records. It is likely to be taken to the European Court of Human Rights.

The UK Prime Minister, Tony Blair has now returned to support for the original wording for European Public Prosecutor’s Office, which includes “serious crimes affecting more than one member state” as well as fraud against the community budget.

Is this a practicality type of question? If so, surely best to start with a limited numbers of offences. But if it is for the investigation of organised crime, isn’t that the wrong way round. One way I’ve heard organised crime defined is “ we know who the bad guys are, we just don’t know what they are up to”. If a database is to be of any use in investigating organised crime it needs to be capable of supporting a proactive investigation, and has to get away from “reactive” thinking.

Or are we talking about an OLAF-style approach, involving a database that can somehow

26

be used to risk-profile new policies for opportunities for organised crime…OLAF reports claim to be able to do this for fraud against the Community Budget.

15) What safeguards could ensure that the transfer of data from your national authorities to the database does not clash your national law?

The Data Protection Act and the European Convention on Human Rights are the two major pieces of legislation that govern UK use of data on databases. In certain circumstances, particularly if it threatened the security of an on-going investigation into serious crime, the request to see what data was held could be refused. This is outlined in the Data Protection Act.

Citizens would have to have a right to ask to see what data was held on them, there would have to be a date by which data was removed, except in the case of paedophiles and terrorist suspects, possibly other categories. The UK Information Commissioner already has the right to inspect data input to the Schengen Information System and similar

European databases.

16) Which national authority within your jurisdiction could undertake the task of transferring the relevant data to the EU database?

.

Have to be NCIS or its successor, unless PITO can be given some form of external jurisdiction as for PNC. An NCIS – PITO partnership would be the most likely body to take responsibility for data transfer. The position of Scotland in the UK means that there is already experience of running such a system. ACPOS says Scotland updates PNC every four hours. Presumably a similar system could be established from PNC to a

European database, but we surely wouldn’t be talking about transferring EVERYTHING would we? There would have to be some decision as to what sort of cases would be involved and how they would be defined as involving organised crime. See answer to question 14.

17) Which national/EU persons may have access to the EU database: judicial, prosecution, police?

For the UK it is and would be NCIS. The Scottish Procurator Fiscal may have a claim but does not at present have access to PNC except via a Police Officer. The Fiscals have a liaison officer to carry out functions normally only carried out by a serving Police

Officer.

27

Elsewhere in Europe it may be judges or procurators. You’re going to end up reinventing

Sirene bureaux, I suspect.

18) Which EU agency could be a suitable host for the EU database? Could Eurojust

(pursuant to Article 14 of the Eurojust Decision) establish a database for investigations and prosecutions that includes relevant data on EU citizens, supervised by a judicial/quasi judicial authority be acceptable to your national legal orders? What problems, if any, would you foresee and how could they be resolved?

The Directorate General of Justice and Home Affairs within the Commission would have to create and build a new database. It would make sense to put it in Strasbourg alongside

SIS2. There are two major systems, the visa information system at Salzburg and SIS2 in

Strasbourg. In Strasbourg is the backup for Salzburg and in Salzburg is the backup for

Strasbourg, if you follow me, the online site for each of these databases is in a different place to the backup site.

It would be a good idea to have a system that could capture criminal convictions based in either Strasbourg or Salzburg. There is in place a new system S (for secure) TETRA

[TErrestrial Trunked RAdio] http://www.tetramou.com/ . This is a network that will enable the exchange of information and may be able to search SIS2 and any criminal convictions database.

The English response is that we need integration, harmonisation and consolidation of existing IT systems, NOT yet another one. STETRA is the most sensible and rational next step forward.

Overall it makes sense to:

1) Define business needs, ie the needs of the Police investigators.

2) Look at Human Rights and data protection problems that would be raised by these needs.

3) Adopt those solutions that could be obtained by adding extra functionality to SIS.

This would cover most of the present problems.

In other words we should take a Police wish list which should go to the politicians in order that they can decide what is acceptable and produce, then, the appropriate legislation.

In the UK it is not necessary to worry about the purpose for which data was entered.

Once it is entered it is available as intelligence or general information. In a number of

European countries you can only look at data in a context similar to that in which it was first entered.

Tampere recommendation 44 set up a Police Chiefs operational Task Force which links

28

to Europol. It has a responsibility to exchange best practice and contribute to the planning of operations. Such an institution is another possible host for a database if it became permanent.

Eurojust or Europol? UK could understand Europol hosting such a database. England and

Wales don’t have a tradition of prosecutors supervising investigation. We will have all sorts of problems adjusting, but we have linked PNC2 to SIS and established a process of data protection and inspection.

The European Public Prosecutor would also be obvious, but the UK is not politically ready for that. Although according to the Financial Times 31.5.04, government sources are saying that the UK could return to a wider role for the EPP, as long as the veto is retained over extensions of the mandate.

The House of Lords European Union Committee has discussed the role of Eurojust in its

23 rd

Report of Session 2003-4. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200304/ldselect/ldeucom/138/138.pdf

para 6 quotes Hans Nilsson, the Head of Judicial Cooperation in the Council Secretariat as saying that Eurojust “ is at the crossroads of two conflicting models: one seeking increased harmonisationof criminal law and procedures and centralised EU structures and the other based on mutual recognition of Member States’ laws and procedures and enhanced cooperation between them.” The UK sees it as the latter, not the former.

Eurojust is a useful institution for exchanging information and facilitating coordination of a prosecution. It is difficult in a UK view to see why it should have access to a database, let alone be the home for one. The UK Information Commissioner even criticised the composition of the Eurojust Joint Supervisory body. He argued that judges might not be experts in data protection and that members of national data protection authorities would be more appropriate. [para 55]