psilocybin - ConvergentEmergence

advertisement

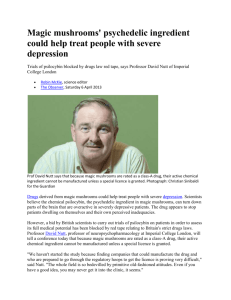

PSILOCYBIN: A NATURAL PHARMACEUTICAL WITH INDISPUTABLE POTENTIAL FOR USE IN PSYCIATRY AND PSYCHOTHERAPY Prepared by Jacob M. Parker Jmparke2@mail.usf.edu August 4, 2009 Parker 1 PSILOCYBIN: A NATURAL PHARMACEUTICAL WITH INDISPUTABLE POTENTIAL FOR USE IN PSYCIATRY AND PSYCHOTHERAPY ABSTRACT This paper covers the basics regarding the identity of Psilocybin, its historical use in humans, and the research that has ultimately led to its classification as a schedule I drug under the United States’ Controlled Substance Act; which, among other things, classifies psilocybin as having no medicinal value. Further discussion will present credible studies and experiments conducted in the past, whose bases explore the effects of Psilocybin and its potential for use in human subjects for the treatment of certain psychiatric disorders. The results of referenced studies will then be compared to the rationale that currently defines Psilocybin as a schedule I controlled substance in the United States. Consequent discussion will reference both current and future studies and experiments being and to be conducted that intend to determine the possible medicinal uses (if any) of psilocybin, and what the results of these experiments may say regarding its viability of use in the fields of psychiatry and psychotherapy. INTRODUCTION Have you ever considered that many pharmaceutical drugs prescribed by specialists to treat psychiatric conditions may only hide the symptoms of the condition and undermine the doctor’s or patient’s ability to confront the issue(s) from which the condition stems in the first place? This paper aims to highlight the potential of psilocybin in its use as a medicinal tool by professional psychiatrists and psychotherapists in their treatment of certain psychiatric conditions. Through additional research, the medical community will become more aware of the medicinal uses that the effects of psilocybin may offer, and how professionals may utilize this chemical in the fields of psychiatry and Parker 2 psychotherapy as a crucial tool for the broadening of comprehension (by both doctor and patient) of the complexities of the individual human mind and resulting interpretations of reality. DISCUSSION Increased research efforts in to the effects of psilocybin on the human mind will undoubtedly provide us with a more direct understanding of our individual consciousnesses and afford an important tool for those professionals in the field of psychiatry and psychotherapy. With the help of the results past research and realizing the effects those studies had on our world, modern researchers may finally begin to study the medical potential of psilocybin from an entirely objective perspective. Psilocybin Identified Psilocybin is a “naturally occurring tryptamine alkaloid” (Griffiths 1) that has been traditionally thought of and generally defined as a hallucinogenic compound— meaning its active chemicals and chemical metabolites induce sensory reactions to impulses that cannot be reasoned to exist in reality. However, there appears to be a great deal of debate among drug researchers as to whether hallucinogenic drugs such as psilocybin actually induce hallucinations. In fact hallucinogenic drugs do not, in general, bring hallucinations…a true hallucination is a perception occurring in the absence of environmental stimulation…So-called hallucinogenic drugs to not cause this. Instead, these drugs simply bring about an alteration in perception or a sense of increased insight or awareness. (Gahlinger 46) Parker 3 Psilocybin is most commonly found as an active chemical constituent of many different species of mushrooms that belong to the psilocybe genus. Ritualistic ingestion of psilocybin by numerous indigenous cultures for spiritual growth is proven to have occurred as early as the sixteenth century, while historical suggestions declare its use up to two-thousand years prior (Jerome 3). In spite of this, several indigenous cultures, who ritualize(d) the ingestion of psilocybin also practice(d) customs whose ideological bases sharply contrast our modern moral understandings, may not necessarily be ideal role models for psilocybin’s medicinal use. For instance, the Aztec people, who were avid users of psilocybe mushrooms, also routinely practiced human sacrifice rituals. Though, a majority of early information concerning the use and effects of hallucinogenic compounds in humans came directly from published field experiences with indigenous peoples who followed strict guidelines surrounding their use of these mushrooms for ceremonial purposes (Johnson et al. 605). Albert Hoffman, a Swiss chemist, first isolated psilocybin from psilocybe mushrooms in 1957, and in 1958 while continuing his research for Sandoz Pharmaceutical became the first person to synthesize the chemical. Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, psilocybin was studied and used by psychiatrists and psychotherapists in their research of improved treatment techniques. Psilocybin and other hallucinogens were completely legal to use and possess by all Americans until 1965. Upon its official induction in to the United States’ list of controlled substances in 1970, psilocybin’s use and research for use in medicine was effectively discontinued. It was not until the mid-1990s that psilocybin resurfaced as the base of research in to its effects on the human mind (Jerome 3). Parker 4 Effects of Psilocybin on the human mind The most notable overall effect induced by psilocybin is the radical alteration of an individual’s conscious perception. In a recent study testing the acute effects of psilocybin, Hasler and his colleagues clarify this perceptive phenomena in their claims that psilocybin has the ability to loosen one’s ego or effectively disintegrate the boundary between the inner self and existing external environment (Hasler et al. 8). They go on to declare: “The loosening of the demarcation between self and environment was generally accompanied by insight and experienced as ‘touching’ or ‘unifying with a higher reality (OB)’” (Hasler et al. 8). Beginning research of psilocybin produced claims that suggest experiences of after-images (the persistence of a perceived image to remain in an individual’s visual field, when in reality the visual stimulus observed had already ceased) as evidence of participant claims of obvious changes in their visual perceptions. Other reports included unusual thought patterns, general feelings of anxiety, and irregular bodily sensations tied to perceived environmental stimuli. A majority early study participants were observed to exhibit noticeable difficulty in performing certain thought related tasks, i.e. basic arithmetic calculations (Jerome 8). When administered orally, the initial effects of psilocybin become apparent to the user within twenty to thirty minutes after ingestion. The peak effects begin to appear between sixty and ninety minutes after ingestion, with all noticeable effects subsiding approximately four to six hours post-initial-ingestion (Jerome 7). The psychological effects of psilocybin include significant alterations in perceptual, cognitive, affective, volitional, and somatesthetic functions, Parker 5 including visual and auditory sensory changes, difficulty in thinking, mood fluctuations, and dissociative phenomena. (Griffiths 2) Physical Effects of Psilocybin The physical effects of the chemical are far less pronounced than those effects seen by the psyche. In addition, various physical effects experienced by a person under the influence of psilocybin may actually be directly triggered by psychological miscues resulting from the psychological effects being experienced. However, research has produced conclusive data that shows consistent physical reactions to the chemical in humans. These effects include: dilation of pupils, and an occasional temporary increase in blood pressure typically in individuals who suffer from cardiovascular conditions such as hypertension (Hasler et al.). A recent investigation into the acute psychological and physiological effects of psilocybin provided the following results: Our investigations provided no cause for concern that administration of PY [(psilocybin)] to healthy subjects is hazardous with respect to somatic health…[and] indicate that PY-induced ASC [(altered states of consciousness)] are generally well tolerated and integrated by healthy subjects. However, a controlled clinical setting is needful, since also mentally stable personalities may, following ingestion of higher doses of PY, transiently experience anxiety as a consequence of loosening of egoboundaries. (Hasler et al. 155) Parker 6 Negative effects The most common adverse effects associated with psilocybin are: distorted awareness of time and space, general feelings of anxiety, “derealization” (losing the ability to tell what is real and what is not), depersonalization (feeling like the idea of the self belongs to someone or something else), experiencing rapid and sometimes powerful changes in positive and negative moods, dizziness, inability to maintain normal levels of concentration, nausea, nervousness, and unusual thoughts and thought patterns. The majority of these effects exist only while the drug is active in the body (four to six hours). (Jerome 15-16) Psilocybin is not linked to any disease of the human body or organ systems (Jerome 15); however the potential for strong psychological reactions while under the influence of chemical have lead some researchers to question whether hallucinogens can be linked to any lasting psychological effects in humans. A study in 2008 sought to answer this question directly, though focused mostly on the lasting effects hallucinogens may potentially have on adolescent minds. The results found that “acute psychotic syndromes in adolescents are rarely due to intoxications with hallucinogenic drugs” (Hermle et al., 1). Nevertheless, psilocybin—if used while not under the supervision of professionals or by individuals who are not aware of the profound psychological alterations the chemical may induce—has the potential to provoke extreme degrees of psychosis in mentally unstable individuals (Jerome, 16-18). The occurrence and intensity of anxiety or panic responses to psilocybin can be reduced through informing participants about drug effects prior to drug administration, supervision and monitoring participants throughout Parker 7 the duration of drug effects by people trained to deal with panic or anxiety, including anxiety in response to hallucinogen effects, and exposure to lower doses before receiving higher doses. (Jerome 16-17) “To date, there have been no verified fatalities directly due to ingesting psilocybin or mushrooms containing only psilocybin and related compounds” (Jerome 15). While there are obviously potential risk factors involved with the use of psilocybin in humans, they compare with those risks taken with the use of various pharmaceutical drugs currently approved for prescription in the United States. For example, psychostimulants such as amphetamine used to treat a variety of disorders from ADD and ADHD to narcolepsy—most notably found as the main ingredient in brand name prescription drugs such as Adderall and Vyvanse (interestingly, both drugs marketed by the same pharmaceutical company, Teva Pharmaceuticals)—have very similar side effects to Psilocybin. These include nervousness including agitation, anxiety, irritability, feelings of suspicion and paranoia, and visual hallucinations. A key difference between the two drugs, however, is the fact that the legal drugs composed of amphetamine have the potential to cause overdose and death, while the illegal drug Psilocybin does not. (www.adderall.net) Past Clinical Studies Throughout the 1950s and early 1960s hundreds of clinical studies were conducted testing the effects of psilocybin and other hallucinogens as means to further the understanding of the human mind. During the same time period, the United States Army and CIA were performing their own experiments with psilocybin on both soldiers and civilians alike. Often times these experiments were seen through without the prior Parker 8 consent of the study subjects, and sought to identify the capacity of hallucinogens to act as truth serums for use in interrogation efforts by the U.S. military (Johnson et al. 605). The majority of early researchers of psilocybin did not anticipate how direct an influence a person’s mindset and perception of their environment actually have on the psychological and physical effects encountered through the experience induced by psilocybin (Griffith 2). Timothy Leary, an early proponent and frontier researcher of hallucinogens, defined these antecedents to the experience (mindset and perception of environment) as “set and setting.” The nature of the experience depends almost entirely on set and setting. Set denotes the preparation of the individual, including his personality structure and his mood at the time. Setting is physical — the weather, the room's atmosphere; social — feelings of persons present towards one another; and cultural — prevailing views as to what is real. (Leary 4) The results of some initial studies reflected an array of negative experiences encountered by study volunteers. Ensuing studies suggested these negative reactions were in part due to the stark environments to which volunteers were subjected throughout the research procedures. Subsequent research, which included more preparation and interpersonal support during the period of drug action, found fewer adverse psychological effects, such as panic reactions and paranoid episodes, and increased reports of positively valued experiences. (Griffith 2) There were also those studies conducted with the direct intention of harnessing the effects of psilocybin and other hallucinogens to be used for the advancement of Parker 9 psychiatric treatments. In this regard, Gahlinger comments on the results of research in the late 1950s to early 1960s, which suggests the potential of hallucinogen-assisted therapy sessions: All psychiatric medications in the 1950s were essentially tranquilizers— they all improved mental illness simply by suppressing the patient’s problems and conflicts. By enhancing awareness, rather than suppressing it, hallucinogens held the possibility that they could resolve these problems instead. (Gahlinger, 49) Results and Effects of the Results of Early Studies The initial research conducted on psilocybin gave doctors and scientists great insight into what the drug could ideally be used for. By the mid-1960s research of psilocybin led to its utilization by psychiatrists and psychotherapists in their patient therapy sessions. Continued research proved that psilocybin could assist psychotherapists and psychiatric researchers in activating an individual’s sub conscious memories and conflicts (Jerome 13). Several experts believed that access to such areas of a person’s psyche would essentially provide the ability of the patient (with the guided support of therapy) to confront their issues and find inner peace. Psilocybin-assisted therapy, as it came to be known, followed either one of two models: the psycholytic model or the psychedelic model. The former involved the ingestion of lower doses of a hallucinogenic drug, and the patient’s active interpretation and analysis of their experience during the session. The psychedelic model used higher doses, and called for the patient to recount their interpretation of their experience after completing the session (Jerome 13). Parker 10 Investigations into the human reactions to psilocybin led to clinical research in to the use of hallucinogens for psychotherapy performed at various universities throughout America. The involvement of university students in the research procedures and the call for student volunteers for the studies eventually led to the popularization of hallucinogens for recreational use. The most notable catalyst for the popularization of hallucinogen use at the recreational level was Timothy Leary, a Harvard professor of psychology who, after his initial experience with psilocybin, endlessly fought for it and other hallucinogen’s recognition as powerful tools in the understanding of one’s own mind. As an almost immediate reaction to the increased recreational use of hallucinogens and other drugs in the 1960’s, the U.S. government passed the Controlled Substances Act, which effectively listed known chemicals with the potential for abuse in to categories known as “schedules.” These schedules have fundamentally become the last word regarding how dangerous each scheduled substance is individually, and dictate the extent of legal punishment in the case of violation. Psilocybin and other hallucinogens became known as Schedule I controlled substances. “Schedule I substances are considered to have a very high abuse potential, no acceptable medical use, and to be unsafe for use under medical supervision” (Gahlinger 76). It is interesting to note that, preceding the U.S. government’s decision to pass the Controlled Substances Act, psilocybin was safely and effectively utilized for psychiatric treatment under medical supervision. A survey gathered data in 1966 that reflected the results of 2,742 individual hallucinogen-assisted therapy sessions, and “found no resulting psychoses, suicide attempts, or uncontrollable behavior” (Gahlinger, 49). Nevertheless, research into the effects of hallucinogens in humans ceased after 1970, and, Parker 11 to date, hallucinogens including psilocybin are still categorized as schedule I controlled substances in the United States. Current and Future Clinical Studies Modern human research with psilocybin only recently began to reappear in the mid-1990s. These studies have examined or are in the process of examining psilocybin’s ability to treat: anxiety related to the diagnoses of terminal illnesses such as cancer, cluster headaches, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Basing their efforts on previously conducted research with LSD-assisted psychotherapy and its uses in the management of anxiety in advanced stage cancer patients, Charles Grob and colleagues are preparing a study focused on psilocybin’s capacity to treat these same symptoms (Jerome 13-14). John Hopkins partnered with Heffter Research Institute and Riverstyx Foundation is also in the process of conducting a similar study with advanced stage cancer patients (MAPS). In 2006 Andrew Sewell and his team studied a group of fifty-three people who suffered from recurring cycles of cluster headaches. The group self-administered psilocybin containing mushrooms as a means to treat their cluster headaches. “Twentyfive of the forty-eight respondents…reported that they had terminated their cluster headache period, and 18 respondents (37%) reported that psilocybin was partially effective in reducing attacks during cluster periods” (Jerome 14). A study done between 2001 and 2004 measured the effectiveness of psilocybin in treating the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder in nine subjects. The results of the study not only associated psilocybin with the “transient symptomatic reduction of OCD symptoms” (Moreno et al. 1738), but also suggested that when administered in a supportive clinical environment, psilocybin was well tolerated and safe (Moreno et al., 1738). Parker 12 Results of Studies and Effects of Current Studies Thus far, nineteen documented studies have attested to the irrefutable psychotherapeutic potential of psilocybin (Jerome 13). While contemporary investigations with psilocybin have provide a limited catalogue of credible studies, many results of past research and speculation regarding psilocybin’s potential role in assisting psychiatrists and psychotherapists have been confirmed by modern research. Such results have prompted more direct interest in researching the uses of hallucinogens for medical purposes. Perhaps one of the most significant products of the resurgence of research with hallucinogens is the ability of modern technologies to aid researchers in disproving countless cultural and politically based myths concerning hallucinogens and other drugs. A key example of such myths may be easily represented by the U.S. government’s claim (evident in their general scheduling guidelines) that psilocybin has a very high potential for abuse. This could not be further from the truth. In fact, recent studies, coupled with information provided by past studies, suggest that the abuse potential of psilocybin is effectively zero (Jerome 18). “Surveys of drug use in the U.S. do not even ask specifically about use of “magic mushrooms, suggesting that use of these mushrooms is relatively uncommon” (Jerome 18). Many such myths, that have tended to become “fact,” have never had any scientific basis, though nevertheless have, for years, fueled a close-minded war on illegal drugs. The ultimate purpose of this war is clearly not to understand why we consider these drugs “bad,” but rather to force the acceptation that they are bad, and forever banish their use into a figurative extinction. Some may simply ask “Why? Why do we advocate the ignorant rejection of illegal drugs instead of allowing educated choices to be made? Why are certain drugs Parker 13 legal and others illegal, while both may hold the same abuse potential or same negative risk factors in common? While there is evidence that may offer support to an infinite number of suitable answers to these and other related questions, it is sometimes better to let evidence speak for itself. A recent report by the Florida Medical Examiners Commission found that the rate of deaths caused by prescription drugs was three times the rate of deaths caused by all illicit drugs combined. The report’s findings track with similar studies by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, which has found that roughly seven million Americans are abusing prescription drugs. If accurate, that would be an increase of 80 percent in six years and more than the total abusing cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, Ecstasy and inhalants. (Cave) Modern research with all drugs, including psilocybin, is beginning to underline our past misinterpretations of their uses and stress the need for further research into how these substances truly affect the human body. CONCLUSION After several decades of discounting the possible medicinal uses of psilocybin— an approach directly influenced by the reaction on the part of the U.S. government to the widespread nonmedical use and abuse of hallucinogens in the mid to late 1960’s— medical research in humans has finally resumed. Modern research methods and technologies have spawned a new interest into the possible therapeutic applications of psilocybin and other hallucinogens (Johnson et al. 616). Through the furthering of such research, and studies that aim to further understand the effects of psilocybin on the Parker 14 human psyche, psychiatrists and psychotherapists may finally possess a key with the potential to unlock the doors of individual perception, and, in doing so, provide specialists and their patients the unique ability to recognize the more deeply seated (perhaps sub-conscious or even unconscious) concerns contributing to their condition(s), effectively allowing for more personalized and successful therapeutic treatments of psychiatric conditions. Parker 15 References "Adderall Side Effects." Drug News. Research Publishing Company, n.d. Web. 26 Aug. 2009. <http://www.adderall.net/>. Cave, Damien. "Legal Drugs Kill Far More Than Illegal, Florida Says ." The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 14 June 2008. Web. 26 Aug. 2009. <http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/14/us/14florida.html>. CESAR (Center for Substance Abuse Research). Dept. home page. University of Maryland. 27 July 2009 <http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/psilocybin.asp>. Gahlinger, Paul, M.D., Ph.D. Illegal Drugs. New York: The Penguin Group, 2004. Griffiths, R. R., et al. "Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-type Experiences Having Substantial and Sustained Personal Meaning and Spiritual Significance." Springer (May 2006): 1-16. 20 July 2009 <http://springerlink.com/content/v2175688r1w4862x/>. Hermle, L., et al. "Hallucinogen-induced psychological disorders." PubMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health . 27 July 2009 <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18512184?ordinalpos=4&itool=Ent rezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_DefaultReportP anel.Pubmed_RVDocSum>. Jerome, Lisa. Psilocybin An Investigators Brochure. MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies). Mar.-Apr. 2007. Multidisciplinary Parker 16 Association for Psychedelic Studies. 20 July 2009 <www.maps.org/research/psilo/psilo_ib.pdf>. Johnson, M. W., W. A. Richards, and R. R. Griffiths. "Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety." Journal of Psychopharmacology (July 2008). 20 July 2009 <http://jop.sagepub.com/cgi/ content/abstract/22/6/603 >. "Psychedelic Research Around the World: Psilocybin Research." M.A.P.S. (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies). 4 Mar. 2009. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 22 July 2009 <http://www.maps.org/research/>.