PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE – TREATING CHRONIC PAIN

advertisement

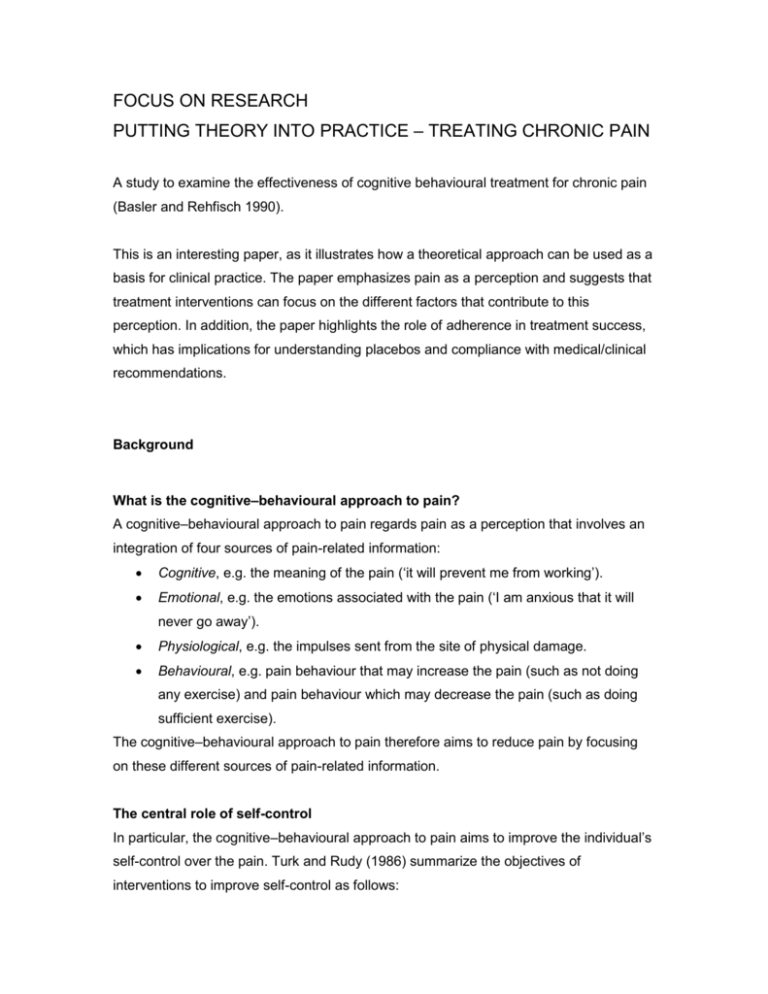

FOCUS ON RESEARCH PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE – TREATING CHRONIC PAIN A study to examine the effectiveness of cognitive behavioural treatment for chronic pain (Basler and Rehfisch 1990). This is an interesting paper, as it illustrates how a theoretical approach can be used as a basis for clinical practice. The paper emphasizes pain as a perception and suggests that treatment interventions can focus on the different factors that contribute to this perception. In addition, the paper highlights the role of adherence in treatment success, which has implications for understanding placebos and compliance with medical/clinical recommendations. Background What is the cognitive–behavioural approach to pain? A cognitive–behavioural approach to pain regards pain as a perception that involves an integration of four sources of pain-related information: Cognitive, e.g. the meaning of the pain (‘it will prevent me from working’). Emotional, e.g. the emotions associated with the pain (‘I am anxious that it will never go away’). Physiological, e.g. the impulses sent from the site of physical damage. Behavioural, e.g. pain behaviour that may increase the pain (such as not doing any exercise) and pain behaviour which may decrease the pain (such as doing sufficient exercise). The cognitive–behavioural approach to pain therefore aims to reduce pain by focusing on these different sources of pain-related information. The central role of self-control In particular, the cognitive–behavioural approach to pain aims to improve the individual’s self-control over the pain. Turk and Rudy (1986) summarize the objectives of interventions to improve self-control as follows: Combat demoralization. Chronic pain sufferers may become demoralized and feel helpless. They are taught to reconceptualize their problems so that they can be seen as manageable. Enhance outcome efficacy. If patients have previously received several forms of pain treatment, they may believe that nothing works. They are taught to believe in the cognitive behavioural approach to pain treatment and that with their cooperation the treatment will improve their condition. Foster self-efficacy. Chronic pain sufferers may see themselves as passive and helpless. They are taught to believe that they can be resourceful and competent. Break up automatic maladaptive coping patterns. Chronic pain sufferers may have learnt emotional and behavioural coping strategies that may be increasing their pain, such as feeling consistently anxious, limping or avoiding exercise. They are taught to monitor these feelings and behaviours. Skills training. Once aware of the automatic emotions and behaviours that increase their pain, pain sufferers are taught a range of adaptive coping responses. Self-attribution. Chronic pain sufferers may have learnt to attribute any success to others and failure to themselves. They are taught to accept responsibility for the success of the treatment. Facilitate maintenance. Any effectiveness of the cognitive behavioural treatment should persist beyond the actual treatment intervention. Therefore, pain sufferers are taught how to anticipate any problems and to consider ways of dealing with these problems. Within this model of pain treatment, Basler and Rehfisch (1990) set out to examine the effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural approach to pain. In addition, they aimed to examine whether such an approach could be used within general practice. Methodology Subjects Sixty chronic pain sufferers, who had experienced chronic pain in the head, shoulder, arm or spine for at least 6 months, were recruited for the study from general practice lists in West Germany. Subjects were allocated to either (1) the immediate treatment group (33 subjects started the treatment and 25 completed it) or (2) the waiting list control group (27 subjects were allocated to this group and 13 completed all measures). Design All subjects completed measures at baseline (time 1), after the 12-week treatment intervention (time 2) and at 6-month follow-up (time 3). Subjects in the control group completed the same measures at comparable time intervals. Measures At times 1, 2 and 3, all subjects completed a 14-day pain diary, which included measures of: Intensity of pain: the subjects rated the intensity of their pain from ‘no pain’ to ‘very intense pain’ every day. Mood: for the same 14 days, subjects also included in the diary measures of their mood three times a day. Functional limitation: the subjects also included measures of things they could not do within the 14 days. Pain medication: the subjects also recorded the kind and quantity of pain medication. The subjects also completed the following measures: The state–trait anxiety inventory, which consists of 20 items and asks subjects to rate how frequently each of the items occurs. The Von Zerssen Depression Scale (Von Zerssen 1976), which consists of 16 items describing depressive symptoms (e.g. ‘I can’t help crying’). General bodily symptoms: the subjects completed a checklist of 57 symptoms, such as ‘nausea’ and ‘trembling’. Sleep disorders due to pain: the subjects were asked to rate problems they experienced in sleep onset, sleep maintenance and sleep quality. Bodily symptoms due to pain attacks: the subjects rated 13 symptoms for their severity during pain attacks (e.g. heart rate increase, sweating). Pain intensity over the last week was also measured. In addition, at 6-month follow-up (time 2), subjects who had received the treatment were asked which of the recommended exercises they still carried out and the physicians rated the treatment outcome on a scale from ‘extreme deterioration’ to ‘extreme improvement’. The treatment intervention The treatment programme consisted of 12 weekly 90- minute sessions, which were carried out in a group with up to 12 patients. All subjects in the treatment group received a treatment manual. The following components were included in the sessions: Education. This component aimed to educate the subjects about the rationale of cognitive behaviour treatment. The subjects were encouraged to take an active part in the programme, they received information about the vicious circle of pain, muscular tension, demoralization and about how the programme would improve their sense of self-control over their thoughts, feelings and behaviour. Relaxation. The subjects were taught how to control their responses to pain using progressive muscle relaxation. They were given a home relaxation tape, and were also taught to use imagery techniques and visualization to distract themselves from pain and to further improve their relaxation skills. Modifying thoughts and feelings. The subjects were asked to complete coping cards to describe their maladaptive thoughts and adaptive coping thoughts. The groups were used to explain the role of fear, depression, anger and irrational thoughts in pain. Pleasant activity scheduling. The subjects were encouraged to use distraction techniques to reduce depression and pain perception. They were encouraged to shift their focus from those activities they could no longer perform to those that they could enjoy. Activity goals were scheduled and pleasant activities were reinforced at subsequent groups. Results The results were analysed to examine differences between the two groups (treatment vs control) and to examine differences in changes in the measures (from time 1 to time 2 and at follow-up) between the two groups. Time 1 to time 2 The results showed significantly different changes between the two groups in all their ratings. Compared with the control group, the subjects who had received cognitive behavioural treatment reported lower pain intensity, lower functional impairment, better daily mood, fewer bodily symptoms, less anxiety, less depression, fewer pain-related bodily symptoms and fewer pain-related sleep disorders. Time 1 to time 2 to time 3 When the results at 6-month follow-up were included, again the results showed significant differences between the two groups on all variables except daily mood and sleep disorders. The role of adherence The subjects in the treatment condition were then divided into those who adhered to the recommended exercise regimen at follow-up (adherers) and those who did not (nonadherers). The results from this analysis indicate that the adherers showed an improvement in pain intensity at follow-up compared with their ratings immediately after the treatment intervention, whilst the non-adherers ratings at follow-up were the same as immediately after the treatment. Conclusion The authors conclude that the study provides support for the use of cognitive– behavioural treatment for chronic pain. The authors also point to the central role of treatment adherence in predicting improvement. They suggest that this effect of adherence indicates that the improvement in pain was a result of the specific treatment factors (i.e. the exercises) not the non-specific treatment factors (contact with professionals, a feeling of doing something). However, it is possible that the central role for adherence in the present study is similar to that discussed in Chapter 12 in the context of placebos, with treatment adherence itself being a placebo effect.