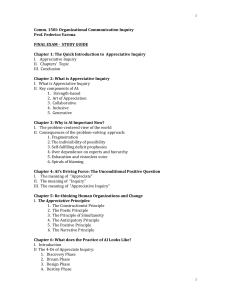

Methods, techniques and concepts for living systems

advertisement