uphold nation city`s cry

advertisement

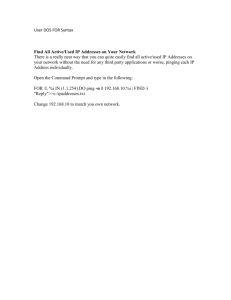

American Styles in USA The four aesthetic modes of Dos Passos’s U.S.A. provide the trilogy with a variety of perspectives on America and American life. The Newsreels, The Camera Eyes, the Narratives, and Biographies each serve to represent different facets and perspectives of America. However, these perspectives are carefully constructed and are not meant to provide an unfiltered view of America; the four modes constitute “an intellectualization of the raw material of American life into a made artwork of great complexity and intricacy” (Pizer 56). Donald Pizer’s use of “intellectualization” is essential because Dos Passos – through a process of parody and narrative manipulation – moulds the raw material it into a new form, which reflects back on the original material. The resultant material is fragmented, representing the alienation present in U.S.A.’s America. However, U.S.A. works to draw together these disparate fragments in order to create a connected whole. This whole is certainly not homogenous, as the alienation and fragmentation demonstrate, but there is a shared history, geography, present, and future. The theory of this essay relies on the anthropologist Benedict Anderson’s idea of “imagined communities”: “nations, as modern social formations, were imagined communities, communities whose imagining was mediated by (and made possible by) the communicative processes and effects of print capitalism and imperial bureaucracies” (Irvine 124). U.S.A. does not promote capitalism and is critical of imperialism and the bureaucratic process, but the notion of a connected community joined together through different media and events is present in U.S.A. It is through the four different modes that Dos Passos simultaneously critiques, fragments, and draws America together. Across America there is a diversity of perspectives and opinions, and Dos Passos’s socialist perspective is all too clear at times, but U.S.A. recognizes the shared stake that all Americans have in the land they occupy. Dedora 2 The Newsreels in U.S.A. function as a commentary on actual newsreels through a selfconscious rendering of newsreel techniques and content. Dos Passos’s Newsreels share many of the same techniques with their source medium through the use of “dislocation and discontinuity” to structure and layout the information being presented (McCabe 12). Furthermore, both types of newsreels share a similar function in the real world and in U.S.A.’s fictional world: “The Newsreels locate the historical background for the action of the trilogy; they provide its setting; they generate atmosphere; they indicate the passage of time in the world and in the text” (Marz 94). On a basic level, Dos Passos’s Newsreels serve to place the other modes within the larger scheme of a teleological world, which is similar to the purpose of real newsreels and how they reported world events to Americans. Charles Marz asserts that the Newsreels chronicle “the voices of the public sphere” and contain the “most banal, most impersonal, most mechanical registration of persons and events in the trilogy” (95). The Newsreels contain elements of the public sphere and discuss events disconnected geographically and politically from the individual reader. “Newsreel XXXVII” demonstrates the impersonal and distant events that people are exposed when viewing newsreels: “SOVIET GUARDS DISPLACED … MACKAY OF POSTAL CALLS BURLESON BOLSHEVIK … REINFORCMENTS RUSHED TO REMOVE CAUSE OF ANXIETY” (69798). The last headline from this passage is particularly alienating because it provides no real information about who is sending the reinforcements, what the anxiety is, and where the situation is occurring. Pizer connects this alienating and distancing effect to how Dos Passos selected headlines that “were indeed obscure to a 1930s reader” (80). The use of obscure headlines serves to heighten the disconnect between world events and the reader. The Newsreels then, Dedora 3 working away Marz’s assertion that they deal with the impersonal and banal, can be read as a parodic manipulation of the heartlessness of real newsreels. The view that Dos Passos’s Newsreels are parody is common amongst criticism of U.S.A. According to Gretchen Foster, “Dos Passos’ newsreels parody the self-serving propaganda handed out by the actual newsreels of the 1920s … as they document and comment on an era” (190). This parody is done through the fusing of “violent contrasts into dynamic montage”; the cinematic technique of montage was commonly used in early avant-garde cinema and involves a series of different angles and shots that are combined together to create a new image in the human consciousness. “Newsreel XIX” represents an example of this parody through its treatment of America’s announcement to join World War I. The Newsreel contrasts the disparate fragments of the financial, politics, patriotism, and racism in relation to wartime America: U. S. AT WAR UPHOLD NATION CITY’S CRY Over there Over there at the annual meeting of the stockholders of the colt Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company a $2,500,000 melon was cut. The present capital stock was increased. The profits for the year were 259 per cent JOYFUL SURPRISE OF BRITISH The Yanks are coming We’re coming o-o-o-ver PLAN LEGISLATION TO KEEP COLORED PEOPLE FROM WHITE AREAS. (312-13) This Newsreel represents how “a particular item or song lyric can stand in clear ironic relationship to the bulk of other items in a Newsreel” (Pizer 82). In U.S.A., there is a clear Dedora 4 undercutting of the newsreel medium and the information they present. However, they form a substantial part of U.S.A. and serve an important role in the modern world. Marz claims that the Newsreels present the “most banal, most impersonal, most mechanical registration of persons and events in the trilogy” (95); however, there is a human element to some of the stories within the Newsreels, which are not satirized. Certain sections of the Newsreels contain elements capable of connecting a distant and unknowable human population. Actual newsreels were able to reach large amounts of people, being played before films, and it is through the human element of stories and exposure through the medium that an imagined community is created. “Newsreel IX” contains a human-interest story of trapped miners and demonstrates the real emotions they go through: I am not afraid to die. O holy Virgin have mercy on me. I think my time has come. You know what my property is. We worked for it together and it is all yours. This is my will and you must keep it. You have been a good wife. May the holy virgin guard you (101). This Newsreel demonstrates that real or fictional newsreels can provide more than information about disconnected and alienating world events. Newsreels can contain snippets dealing with powerful stories of human life, which have to be filtered out from the fragmented chaos of parody and alienation. The emotional impact of “Newsreel IX” creates a sense of human unity through the recognition of shared fears and hardship. The Camera Eye sections of U.S.A. are recognized as the most ambiguous mode used by Dos Passos. Pizer asserts that The Camera Eyes are “a coherent autobiography” of Dos Passos, as they are an “account of Dos Passos’ inner life” (57). Dos Passos has stated that The Camera Eyes contains “bits of my [Dos Passos’s] experience” and function as “a way of draining off the subjective” from the rest of U.S.A. (qtd. in Hock 21). However, knowing Dos Passos’s life, and Dedora 5 that the Camera Eyes can be considered autobiographical, is not necessarily essential to read U.S.A. If the reader does not know that The Camera Eyes are autobiographical, and that the personal information in them is that of the author, the notion of draining off subjectivity has to be questioned. For Justin Edwards, The Camera Eyes are a very intimate and personal account within U.S.A. and “depict the consciousness of the individual subject, expressing the thoughts, emotions and perspectives” (247). Problematically, Edward ties these thoughts and expressions to Dos Passos, but his identification of the individual consciousness within The Camera Eyes is essential for understanding them and their relation to U.S.A. as whole. The Camera Eye mode is the only mode written in a first person narrative voice. Within the Narratives and Biographies a third person narrator is dominant. For Stephen Hock, The Camera Eye provides “a glimpse of the position that Dos Passos presents as the most deeply felt of all, because it represents his own subjective position within the world that he describes only at a distance in the other sections of the text” (21). However, Hock’s assertion, and the other critics from above, is problematic when the language and use of perspective in The Camera Eye is examined. An example of the individualistic nature of The Camera Eyes is “The Camera Eye (26)” with its first person perspective on the labour movement: we couldn’t get a seat so we ran up the stairs to the top gallery and looked down through the blue air at the faces thick as gravel and above them on the speaker’s stand tiny black figure and a man was speaking and when ever he said war there were hisses and whenever he said Russia there was clapping … afterwards we went to the Brevoort it was much nicer everybody who was anybody was there and there was Emma Goldman eating frankfurters and sauerkraut and Dedora 6 everybody looked at Emma Goldman and at everybody else that was anybody and everybody was for peace … and we had several drinks and welsh rabbits and paid our bill and went home, and opened the door with a latchkey and put on pajamas and went to bed and it was comfortable in bed (301-302). The issue in “The Camera Eye (26), and others, is that the first person narrative voice is limited to expressing observations of the exterior world. Instead of capturing a subjective and opinionated view of the world, “The Camera Eye (26)” only captures sounds of clapping, images of faces, food, and drink. The only personal expression is directed at an inanimate object and not the political movement: “it was comfortable in bed.” The Camera Eye sections cannot express a subjective perception of the world because they function similar to a mechanical camera. The words used in the title of The Camera Eye sections cannot be ignored when examining The Camera Eyes. The use of “camera” denotes a recording of the exterior world, while “eye” invokes the lens in the camera. In opposition to this analysis, Pizer points to “The Camera (28)” as containing the “the variations of style used for the expression of the interior self” (58). In order to come to this conclusion, Pizer focuses on “personal images that are knitted together by a parallel rhetorical form” (369); however, the essence of The Camera Eyes is the images. In “The Camera Eye (28)” the speaker experience the death of his mother and father, yet the first person voice does not express any emotion: when his father dies the narrator states, “I walked through the streets full of fiveoclock Madrid seething with twilight in shivered cubes of aguardiente redwine gaslampgreen sunsetpink tileochre eyes lips red cheeks brow pillar of the throat climbed on the night train” (369). Pizer is able to read poetic meaning into this Camera Eye, but the subjectivity rests within the reader and how she/he decides to understand Dedora 7 metaphors, symbols, and rhetorical form. The Camera Eye sections only provide a sense perception of the world and not an emotional rendering, as seen in how the response to death is only a description of Madrid. The Camera Eyes attempt to understand the world through a method similar to a camera. This method is closer to an unmediated vision of events than the third person narration of the Biographies and Narratives. The result, in relation to the work as a whole, is an individual view of the world, but it is only individual to a certain extent. The imagistic recordings function to unite people around perception of sound and images. In Madrid or at the socialist meeting, every person present shares in the same sounds, smells, and sights, which creates a unity of people in spite individualistic leanings. The Narrative sections function to place characters within the larger forces of the world. The Narrative sections – unlike the ambiguous The Camera Eyes that are not labelled as belonging to one person – are each clearly labelled according to the character the particular Narrative functions around. The Narratives, for Edwards, are relatively free of “authorial intrusion” as they “simply report on the actions and thoughts of the characters” (249). This technique serves to “achieve the highest degree of objectivity” because the characters become the “medium through which their stories receive expression” (Gelfant qtd. in Edwards 249). The narrator is not all knowing and only provides the emotions and thoughts of the character that each Narrative is named after. This technique serves to demonstrate to the reader the isolation of the characters in the world because they are left wondering, like the reader, the motivations of other characters. The use of multiple narratives and the authorial controlled third person narrator is essential because it provides a diversity of unique, but isolated, perspectives. The interaction of characters demonstrates this point, and particularly how Mac, Moorehouse, and Janey all meet in Mexico because the oil crisis. Mac goes to Mexico for the revolution, while Moorehouse and Dedora 8 Janey go because of the American capitalist concerns surrounding the Mexican oil industry. During this interchange, under Mac’s Narrative, Moorehouse and Janey are alienated and “looked scared to death” (276) when presented with a form of entertainment that Mac enjoys. The intrusive narrator only serves to heighten each character’s isolation from others. The characters only have access to their own thought, and through the controlling narrator the reader is limited to the thoughts, motivations, and emotions of a single character. The isolating nature of the Narratives opens up a discourse on how the Narratives function to reflect and connect American people. The Narratives are not a “representative sociological spectrum of American life,” as they lack “a farmer, factory worker, businessman, or professional” (Pizer 64). The limited source of the characters that the Narratives follow is representative of the limited third person narrative style. A dialogue by the character Richard Ellsworth Savage functions to demonstrate the thematic and stylistic purpose of the Narrative sections: He wished he had a great many lives so that he might have spent one of them with Anne Elizabeth. Might write a poem about that and send it to her. And the smell of the little cyclamens. In the café opposite the waiters were turning the chairs upside down and settling them on the tables. He wished he had a great many lives so that he might be a waiter in a café turning chairs upside down (695-96). Savage’s dialogue represents the significance of a limited narrator because he recognizes the limits of experience and the ability to experience the way other people live. Savage has limited experience in life, and the narrative structure mirrors this through its isolated viewpoint. For Pizer, the Narratives are further limited because the characters are only representative of “prototypes in Dos Passos’ own experience, and Dos Passos recasts the lives of his prototypes Dedora 9 into narratives” (Pizer 64); however, the limitation, of the narrow spectrum of society from which the Narratives are pulled, is not full. While Savage is limited in his outlook on the world, and the reader is limited by Dos Passos’s use of a limited third person narrator, there is an interaction with the whole spectrum of the American populous. Through the main Narratives, the whole spectrum of America is shown from the Farmer to the East coast, and while the perspective is always limited, there is an interaction between the Narratives and every facet of America. This demonstrates how a very limited basis for character selection has the possibilities to show an entire country. The use of an intrusive narrator, that can only provide information on one character’s interior life at a time, functions to demonstrate the isolation of individuals. However, the irony is that through this isolation there is still a national connection as characters continually interact with the world and people around them. The fact that Dos Passos selects a very specific group of characters for the Narratives who are able to connect with nearly every facet of American life demonstrates the strange vision of unity Dos Passos has of America. The Narratives are representative of regular Americans and they work in tandem with the Biographies that represent famous Americans. Unlike the Newsreels and The Camera Eyes, the Biographies are labelled similar to the Narratives. The Biographies provide an alternate perspective of America, as compared to the Narratives, through the use of public figures involved in politics, business, science, the arts, and journalism. However, this perspective is problematized by Dos Passos’s treatment of biographical techniques and the figures. According to Pizer, Dos Passos “had available to him in the 1920s an emerging convention for the kind of biography he wished to write” in the works of Lytton Strachey and Thomas Beer who “popularized the ironic impressionistic biography in which a seemingly miscellaneous body of biographical detail produced a devastating reversal of received opinion about a major public Dedora 10 figure” (75). U.S.A.’s Biographies function to revaluate historical personages and their relation to American society. The Biography “The Happy Warrior” demonstrates this revaluation, but also functions to connect these historical personages to American values and life. The Biographies simultaneously isolate the figures from regular Americans while demonstrating the figure’s social significance in relation to American society. Teddy Roosevelt, “The Happy Warrior,” had a large impact on American society: he promoted nationalistic causes and was “an unapologetic imperialist who called his domestic program ‘the New Nationalism’” (Leach 11). Roosevelt was involved in the formulation of the imperialistic American project as he “sent the Atlantic Fleet around the world for everybody to see that America was a firstclass power” (Dos Passos 483-84). Roosevelt was a mover of world events, and Dos Passos provides a particular lens into this personage, but guides the interpretation of Roosevelt by using statements such as “righteousness was his by birth” (480), he “stoutly maintained that white was white and black was black” (482), and he “left on the shoulders of his sons the white man’s burden” (485). These statements provide the ironic undermining that, according to Pizer, occur in Dos Passos’s biographies and function to revaluate Roosevelt’s contribution to American society. However, Dos Passos also demonstrates that Roosevelt is still an American by revealing his homey nature as “a rancher on the Little Missouri River” (481), how he patriotically made sure “Old Glory floated over the Canal Zone” (483), and how he liked having “pillowfights with his children” (485). The Biographies serve to examine the movers of American society, but never separates the figures from America itself. The end result of the four different modes is U.S.A. Taken as individual modes they appear as fragmentary and represent the alienating nature of life in Dos Passos’s America. Dedora 11 However, the sections invariably work in unison to draw together the disparate parts of America into a form of unity. From the lowest figure to the president of America, a tenuous union between people is formed. It is through the Newsreels and Biographies, which are inherently ironic in order to critique the source forms and content, that this union is possible. People such as Roosevelt, Wilson, and Jack Reed are re-evaluated, but in doing so are placed into the same events that the characters in the Narratives experience. The Newsreels function to connect people across the nation through the propagation of shared events and common values. While many of these values are constructed by the media and then embodied by the American people, there is still that union. The Camera Eyes serve to tie all these points together because they are an individual’s recordings of the world, but it is a world that is shared in perception. Works Cited Dos Passos, John. U.S.A. New York: Library of America, 1996. Dedora 12 Edwards, Justin. “The Man with a Camera Eye: Cinematic Form and Hollywood Malediction in John Dos Passos’s The Big Money.” Literature Film Quarterly 27.4 (1999): 245-54. Foster, Gretchen. “John Dos Passos’ Use of Film Technique in Manhattan Transfer and The 42nd Parallel.” Literature Film Quarterly 14.3 (1986): 186-194. Hock, Stephen. “‘Stories Told Sideways Our of the Big Mouth’: John Dos Passos’s Bazinian Camera Eye.” Literature Film Quarterly 33.1 (2005): 20-27. Irvine, Judith T. “Language and Community: Introduction.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 6.2 (1996): 123-25. Leach, Eugene E. “1900-1914.” A Companion to 20th-Century America. Ed. Stephen J. Whitfield. Malden: Blackwell, 2004. Marz, Charles. “Dos Passos Newsreels: The Noise of History.” Studies in the Novel 11 (1979): 194-200. McCabe, Susan. Cinematic Modernism: Modernist Poetry and Film. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005. Pizer, Donald. Dos Passos’ U.S.A.: A Critical Study. Charlottesville: Virginia UP, 1988.