Gershom Scholem`s Linguistic Theory

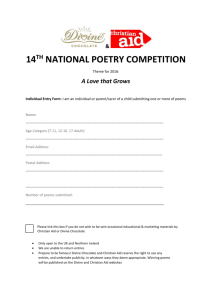

advertisement