The New United States

advertisement

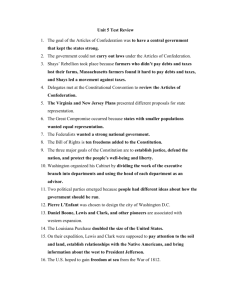

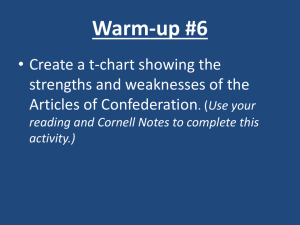

The New United States: Articles of Confederation Mr. Kemper Once the colonies had broken away from British rule, the independent new nation needed a plan in order to govern itself. Americans agreed that their nation should be a republic, a government in which citizens rule through elected representatives. Also, Americans agreed that the national government ought to have less power than the state governments. Americans had just rid themselves of Britain’s tyrannical government under King George III. They did not want another despot controlling them. The first plan of American government was called the Articles of Confederation. In this sense, “articles” means items in a plan; “confederation” means a group of allies. Under this plan, the new nation was a “firm league of friendship” in which each state retained “its sovereignty [ability to rule itself], freedom, and independence.” The national government was given the power to conduct foreign affairs, maintain armed forces, borrow money, and issue currency. Under the Articles of Confederation, states were very much like small, independent countries. They would act alone on most issues, and work together through a central government only when conducting international affairs, such as war and diplomacy. The new national government under the Articles of Confederation had many weaknesses. It could not pass a law unless at least 9 of the 13 states voted in favor of it. Any attempt to change the Articles of Confederation required the consent of all13 states. These strict voting requirements made it difficult to pass or change laws. The national government was not allowed to regulate trade, draft (force) soldiers into the army, or impose taxes. If the national government needed to raise money or troops, it had to ask the state legislatures. However, states were not required to contribute. The national government had no chief executive, or leader, to enforce its laws. The new country was in an economic depression. Because the national government had no authority to collect taxes, the national Congress and the states had printed their own paper money. Since neither gold nor silver backed up these bills, the value of the money plummeted, while prices of food and other goods soared. Between 1779 and 1881, the number of American dollars required to buy one Spanish silver dollar rose from 40 to 146. Because the Confederation government could not tax citizens, it could not pay its debts – it still owed Revolutionary soldiers their pay for military service, and it owed American citizens and foreign governments for money borrowed to fight the war. After the war, economic activity had slowed and unemployment had risen. Trade also fell off when the British closed the profitable West Indian market to American merchants. What little money there was went to pay foreign debts. Money was in short supply. Farmers suffered because they could not sell their goods. Southern plantations had been damaged in the war and rice exports had dropped sharply. Farmers had trouble paying state taxes designed to meet Revolutionary War debts. State officials seized farmers’ lands to pay their debts, and many indebted farmers were put in jail. The farmers became angry. In 1786, some farmers took the law into their own hands. Led by Daniel Shays, a former Patriot army captain, they rebelled against the confiscation (taking) of their land. More than 1,000 farmers protested. The uprising was put down after four of Shays’s men were killed. Shays’s Rebellion frightened many Americans who worried that the government could not control unrest and prevent violence. When he heard about the rebellion, George Washington wondered whether “mankind, when left to themselves, are unfit for their own government.” Thomas Jefferson, away in France at the time, felt differently. He wrote, “A little rebellion, now and then, is a good thing.” In its strong desire to avoid a new tyranny, the new nation overcompensated by not giving enough power to the national government. The shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation would be taken into account when the new nation revised its plan and called it the U.S. Constitution.