Linguistic Anthropology: “Reading” the “Texts” of Social Interactions

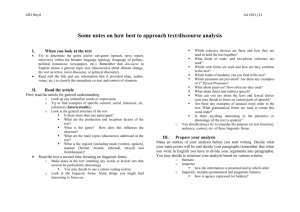

advertisement

Linguistic Anthropology: “Reading” the “Texts” of Social Interactions Framing What We Do In studying “the linkages between linguistic and social structures” linguistic anthropologists take both very seriously as matters for theorization and empirical investigation. These two “structures” turn out to be only indirectly related one to another as structures, though each is ultimately unanalyzable without attention to the other. On one side, linguistic structure manifests empirically in facts of discourse, which, to be rendered into anything more than noise – for participants as well as for analysts – must be rendered into texts-in-contexts under a theory of how instantiated grammatical form (discourse parsed into text-sentences) and metrical (“poetic”) form (discourse parsed into metrical principles of recurrent equivalences), ordinally vs. cardinally distributed constituent units of larger forms, interact in achieving denotational textuality. Only under such a double parsing does the phenomenon of indexicality – in social formations, always conventional indexicality – make its face known, indexicality of the three discernible kinds: cotextuality [text-internal principles of cohesion in principle independent of grammar, e.g., parallelism, repetition, constituent ordering by “weight,” phonological and semantic tropes, adjacency pair-part role alternation, etc.]; deixis [the indexical component of denotation, where co(n)textualization and denotation intersect, e.g., ‘person’al (communicative-role), locational, temporal, epistemic, logophoric deixis – most of the “D” and “I” operators of DPs and IPs, etc.]; non-denotational social indexicality [e.g., all “sociophonetic” indexicals, deference-and-demeanor indexicals (“politeness” in the literature uninformed by social science), occupational and other identity register-shibboleths, etc.] Texts gel in socio-spatio-temporal realtime, the coming-into-being in other words of the distinction of ‘text’ and ‘context’, viewable as the complementary processes of entextualization/contextualization; and the text vs. context relationship, though always inherently subject to further transformation, becomes thicker and more difficult to undo as determining of further interactional coherence as already experienced cotext itself turns into “prior,” i.e., presupposable context for participants in its co-construction. (Thus, the field of linguistics in its normative practice imagines one-text-sentence-long texts as first adjacency pair-parts in asymptotically vanishing presupposed context as its closest phenomenal object of investigation.) On the other side, we recognize that discourse, functioning as the central medium of social interaction, thus always instantiates recognizable cause-and-effect social events (sometimes even linked essentially to imagined future ones, such as my act of composing these lines in anticipation of the conference event, having seen the list of invited coparticipants). All discourse is thus always “perlocutionary,” if not always successfully targetable in desired outcome according to “illocutionary” conventionality. But there are normative genres that associate certain text-sentence-length formal ready-mades, e.g., explicit primary performative constructions with distinct metapragmatic lexical verbs (I promise/order/etc. you that/to [S]), with certain adjacency pair-part expectations; and as well various normative metricalizations otherwise characterizable that language users recognize – and linguistic anthropologists come to know via ethnographic investigation – 2 as relatively set genres of interactional textuality involving more than one participant, e.g., “Getting-to-Know-You” or “Interrogation-of-a-Party-as-Good-Cop-Bad-Cop” in our culture; “Why-I-Don’t-Have-A-Spirit-Power” among Northwest Native Americans of the Plateau region, etc. In this way, all discursive occasions comprise the experienceable social events of what social scientists term social organization, the processual manifestation of social structures in experienceable and observable social practices; what is revealed to systematic analysis is the way that people of particular positions within structures of social differentiation in society are recruited to interactional roles with certain understandings of how they may – note the normativity of the modal! – comport themselves with respect to certain social others (think partitional or gradient structures of age-set or age-grade; of kinship; of gender; of ethnicity; positional status within a firm or like organization; of clan; of moiety; of profession; etc.). So social structures, like linguistic structures, are only immanent in discourse-mediated social interaction, indexically presumed upon and indexically – performatively – renewed (even potentially transformed) in-and-by events of social interaction. Depending on whether we examine individual discursive events as countable instances under a theory of interactional genre, as do our “CA” brethren, who presume to extract schemata of commonalty across what they take to be interactional sequences of comparable type (same genre), or whether we study interdiscursive chains of communication, longitudinally tracing the interactional behavior of people following same or similar interactants, or interactants seemingly connected in a network of such, we discover more and more encompassing social structures insofar we can discern normative regularities with reference to which such events and chains of events are interpretable with reference to a theory of group-relevant social differentiations. People in societies not only reveal the immanence of social structural differentiations relevant to their role-relational mutual coordination, they develop elaborate metapragmatic intuitions about these indexically manifest relationships that bias their own usage of linguistic forms and their interpretation of the usage of others. Frequently, these intuitions are externalized in metapragmatic discourse in systems of valorization, articulating value loadings of one or both of the indexically connected phenomena of linguistic and social structure, i.e., language forms and social statuses, along dimensions of evaluation, intuitions of ‘good’—‘bad’ or ‘better’—‘worse’ inherent in how these line up. Indexicality is thus always a dialectical fact of language-in-use, duplex in character (indexical by virtue of a metapragmatics; metapragmatically visible by virtue of form— context reflexive consciousness) and thus inherently unstable. (And of course all language-in-use is an exercise in indexicality “all the way down.”) Such ideological loadings, then, drive change in time, as the cumulative bias of prescriptive or proscriptive metapragmatic stipulation influences how people use linguistic form to be – or to avoid being – persons of certain identifiable social types under certain social-contextual conditions. Current Horizons 3 We have a fairly detailed idea of how the only apparently isolable facts of “what we say,” i.e., the denotational text-in-context, comes to “count-as” [the illocutionary theorist’s usage for ‘projects into’] “what we do” with words, one modality among all the cultural semiotics we employ in discursive interaction to bring about cause-and-effect self- and other-identification and social recognizability, “identity work,” on which rests how we can coordinate with others as social agents. We have studies of many different kinds of cultural schemata of valorized social differentiations indexed by particular language features on social occasions of speaking, and elaborate studies of the cultural ideologies in schemata of valorization that allow people to “read” each other in local cultural terms, whether as to ethno-theories of intentionality framed as “motivation,” “affect/emotion,” “calculative rationality,” etc. One horizon of current investigation is implied in the term interdiscursivity, implying multiple discretely experienced events of communication where commonalty of messages and/or participants obtains: the circulation of indexically signaled values in groups and across categories of people in society. Where do values ‘emanate’ from? (We have detailed knowledge of explicit ritual contexts that reinforce values in relation to social differences, of course, one of the centerpieces of social anthropology over the decades. But how do particular sites of innovative usage come to set value that spreads across a category of people, or in a group of people [not the same social thing, note!]?) Do acts of communication in network chains follow institutionalized routes of circulation of indexically signaled value? (Mass media need careful study for the way that mediatized messages may be central to mediation of such indexically signaled values in complex, mass social formations.) Do changes in indexically signaled values follow such routes? Does this lead to realignments of identity as shibboleths emerge to new normativities of usage? How does ideological discourse drive such change “from above” as a function of its site(s) of emanation? In matters of words and expressions – elements of denotational text in the first instance – we already know of the multi-componential nature of the ‘meaning’ of anything we might want to associate as the cued significance of use of a token of a word, of a collocation, etc. Putnam’s philosophical arguments (concurrently and independently reinforcing of my own work on indexicality) show us that all words and expressions in parsable text are irreducibly indexical in character, under ‘the sociolinguistic division of denotational labor’ indexing ultimately identities within schemata of social differentiation (how a chemist uses the term water in disciplinarily contextualized discourse thus indexes her identity as chemist – and may do so by the peculiarity of interdiscursive echoes of such usage even when she is on the golf links). How do the group-relative and thus identity-indexing stereotype concepts cued by word- and expression-usage interact – sometimes in tension – with the grammatico-semantic concepts implied by the distributional facts of form-class membership in grammatical structure? Do stereotypes historically become grammatico-semantic projections? What does this possibility say about the nature of grammatical normativity – as opposed to the irreducible indexicality of all language-in-use – at least in respect of the internal structure of lexical classes functioning in a grammar? 4 Also, one of the key results of this indexical approach to language-in-use is – consistent with what Labov discovered in regimes of fierce, institutionalized language standardization – that as ideologically infused metapragmatic (un)consciousness of indexicality engages with such indexicality, it defines not just individual punctate indexicals (in variationism, an unexamined holdover from the notion of individual Lautgesetze affecting a single phoneme or phonetic segment-type, now viewed as an isolable “variable”), but in fact it stimulates the coming-into-being of registers of variance, sets of coherent cooccurrences normative for particular contextual conditions of language-in-use, some features of which are more salient than others, thus functioning as performable shibboleths of the occurrence of the register as such. (Think of the Japanese, Javanese, Tibetan, etc. phenomenon of ‘speech levels’; also Ferguson’s “sport’s announcer talk,” or “baby talk” as registers defining indexically coherent vs. incoherent usage.) Enregisterment is the basic condition of language, and anything we might want to term a ‘language’ is, as an empirical reality, the logical union of all its occurring registers at any socio-historical moment. What are the limits of enregisterment? How are its shibboleths, highly salient indexicals that skew interpretation of everything else, emergent from the dialectic of usage and ideology? How is ‘style’ really a phenomenon of register, and not of individual indexically loaded variables? How, finally, are the phenomena that Martinet first postulated of a linkage of variables in “push-pull” chains, as much to be located in phenomena of enregisterment – with which a behavioral Gestalt of a kind of stereotypic character can be linguistically and paralinguistically performed – as they are in phenomena like cognitive-structural symmetry of phonological and other categorial systems of grammar (which always seem to allow phonetic coincidence of underlyingly distinct phonological units)? These are a few of the horizons of investigation to which contemporary linguistic anthropology has come.