The Collapse of the Soviet Military

advertisement

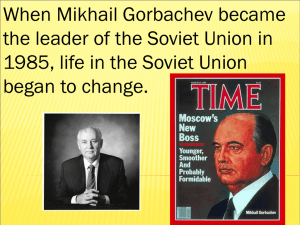

Book Review The Collapse of the Soviet Military William E. Odom, The Collapse of the Soviet Military. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998. 523 pp. This new book by William Odom, one of the foremost experts on the Soviet military, addresses an extremely challenging question: How and why did the Soviet military collapse? This question cannot be answered without reference to larger political and [End Page 132] economic forces, particularly the sweeping reforms launched by Mikhail Gorbachev. The book thus addresses a broader topic than the title implies: the role of military factors in the collapse of the Soviet Union. Odom's explanation of why the military collapsed is disarmingly simple: "Gorbachev made it collapse" (p. 392). Although Odom devotes considerable attention to larger structural factors, he ultimately concludes that Gorbachev's leadership and decisions were the "critical precipitating factor" (p. 393). Odom's portrait of Gorbachev hews closer to John Dunlop's interpretation of Gorbachev as a duplicitous schemer ignorant of the Soviet system's fatal flaws than to Archie Brown's depiction of a true social democrat who overcame nearly insurmountable obstacles to liberate his country from tyranny and the world from a deadly arms race. Odom's view of Gorbachev is evident in his discussion of economic reform, particularly reform of the military-industrial sector. Odom highlights economic decline as a key impetus for Gorbachev's international and domestic reforms. In Odom's view, Gorbachev naively believed that he could fix the economy by transferring resources from guns to butter, rather than by introducing fundamental changes in the system. Odom concludes that "perhaps Gorbachev's inability to understand this issue conceptually was actually a blessing. Had he understood, he might have given up on perestroika" (pp. 241-242). The book begins with five solid chapters on the foundations of Soviet military policy. Odom's chapters on organizational structures, manpower policies, and the military-industrial sector represent some of the best introductions to these topics available. Those on ideology and military strategy are inherently more controversial. Odom restates his long-held views that MarxismLeninism was the most important guide to Soviet military planning, and that the Soviet leadership's view of nuclear weapons and war-fighting was fundamentally different from the American approach. He brings little new evidence to bear on these questions, however, and is unlikely to persuade experts who disagree. Odom moves on to consider the entire range of military issues that civilian and military leaders confronted during perestroika: doctrinal reform, arms control, glasnost, the role of the Communist Party in the military, manpower policy, "conversion" of military industries, and the use of the army to cope with internal unrest. Odom's treatment of these issues is excellent. His many years of study of Soviet military affairs give him a firm grasp of the roots of problems that first received public attention during the glasnost era. His discussion of the origins and consequences of dedovshchina (the hazing of first-year conscripts by second-year troops) is probably the best available in English. Odom's own experience as a military officer allows him to appreciate the formidable problems that the Soviet High Command faced in implementing major policy changes. Civilian reformers in the Soviet Union tended to be much less aware of these practical difficulties. At the same time, Odom makes no apologies for corruption and "old thinking" in the senior officer corps. Odom traces the beginning of the end to 1988, when Gorbachev initiated bold political reforms and announced unilateral cuts in the Soviet armed forces. Odom contends that military reform, broadly defined, was the key to Gorbachev's entire program. [End Page 133] According to Odom, the size of the military burden and the importance of the army as the "last defense against destabilizing forces" (p. 396) ensured that the military issue would be at the heart of any serious attempt to enact broader reforms. He demonstrates that manpower policies increasingly spun out of control from 1989 to 1991, starting with the withdrawals from Eastern Europe and ending with a massive "conscription revolt" in the Soviet Union itself. He argues persuasively that these problems played a more important role in the Soviet collapse than is commonly appreciated. The failed August 1991 coup attempt and the final months of the Soviet Union are explored in the last chapters of the book. Odom sees the August events as less a coup than a power struggle within the Communist Party. He thus seriously downplays the radically different context that democratization had brought about, including Gorbachev's dual status as General Secretary of the Communist Party and president of the USSR. The army's passive role in August is explained as a consequence of the lack of cohesion in an internally divided military establishment. What Odom calls the "fizzle and farce of the Soviet military's last days" is seemingly explained in similar fashion, although he is less clear on this point (p. 373). Odom also stresses the close entanglement of the army with the party as a source of military inactivity, a view he first articulated over twenty years ago. Odom somewhat glosses over his previous writings, which implied that the military was simply the "executant" of the Party, and therefore that conflict between the military and civilian leadership was impossible. Alternative explanations of the army's behavior in the final months of Soviet power, such as a tradition of subordination to civilian rule, are not discussed in any detail. Odom has made good use of many new sources that became available because of glasnost and liberalization. His use of interviews with many high-level Soviet officials, civilian and military, is particularly impressive, although at times he may have been well advised to take a more skeptical approach to their testimony. Despite Odom's detailed research, he unfortunately overlooked some crucial sources, including archives, memoirs, and published interviews and documents. He made no use of the materials in Fond 89 from the Communist Party archive, nor did he consult important published documents, such as the reports by the Soviet prosecutor and the Sobchak Commission on the events of April 1989 in Tbilisi, the transcript of the December 1988 Politburo meeting following Gorbachev's landmark speech at the United Nations, and the depositions of Generals Boris Gromov and Pavel Grachev regarding the August 1991 coup. He also failed to draw on many of the important memoir accounts that are now available, notably the account of General Leonid Ivashov, who worked closely with Minister of Defense Dmitrii Yazov, and Mikhail Gorbachev's own autobiography. The Collapse of the Soviet Military is the most comprehensive treatment yet of the Soviet military's final years, and a worthy summary of Odom's decades of research on the Soviet armed forces. Students of Soviet politics and history will find a great deal of value--as well as some points to dispute--in this impressive volume. Brian D. Taylor University of Oklahoma