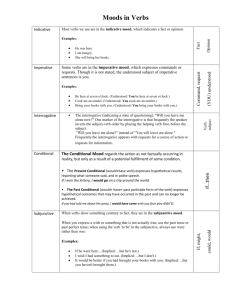

The table below outlines the constructions which will be covered:

advertisement

The table below outlines the constructions which will be covered:

Week

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

Construction

Introduction

Syntax Consolidation: Nouns

Syntax Consolidation: Adjectives, Adverbs and Comparisons

Syntax Consolidation: Active Verbs

Syntax Consolidation: Passive Verbs

Direct Questions, Commands and Prohibitions

Infinitive and Indirect Statement I

Infinitive and Indirect Statement II

Participles

Ablative Uses and Ablative Absolute

Dative Uses and Predicative Dative

Genitive Uses

Relative Clauses

Syntax Consolidation: Subjunctive Verbs

(including Independent Subjunctives: Jussive, Deliberative, Optative)

Indirect Commands and Exhortations

Purpose Clauses

Result Clauses

Indirect Questions

Temporal Clauses (including cum)

Causal Clauses

Concessive Clauses

Comparative and Correlative Clauses

Indicative Conditionals

Subjunctive Conditionals

Gerunds and Gerundives

Gerundives of Obligation

dum and dummodo

Verbs and Phrases of Fearing

quomodo and quin

Oratio Obliqua

1

Language: Week 2

Syntax Consolidation: Nouns and Adjectives

Before embarking upon advanced linguistic work, it is absolutely essential to ensure

that your knowledge of basic Latin accidence is absolutely rock-solid.

This week, you should revise the cases and declensions of Latin nouns and adjectives.

You will need to be able to recognise the case and number of a Latin noun or

adjective from any of the five Declensions, and to understand the basic range of

meanings which each of the cases possess:

NOMINATIVE

Subject of the sentence; the person or thing who is doing the action described by the

verb:

The slave pruned the vines

ACCUSATIVE

Object of the sentence; the person or thing to whom the action described by the verb

is being done:

The slave pruned the vines

After a number of prepositions

GENITIVE

Possessive, meaning “of”: The food of the slave

After a number of prepositions

DATIVE

Indirect Object, meaning “to” or “for”:

The overseer gave food to the slaves; The slave carried the wine-jar for his master

After a number of prepositions

ABLATIVE

Basically, “by”, “with” or “from”:

The master beat the slaves with a stick

After a number of prepositions

You must thoroughly revise the noun and adjective tables which can be found at:

Palmer Latin Language pp. 142-143

or

Kennedy Revised Latin Primer pp. 17-18, 22-26, 30-31, 37-40

When you are confident that you are familiar with noun and adjective endings, follow

this link to the Nouns self-assessment exercise.

2

Language: Week 3

Syntax Consolidation: Comparison of Adjectives and Adverbs

Before embarking upon advanced linguistic work, it is absolutely essential that you

ensure that your knowledge of basic Latin accidence is absolutely rock-solid.

This week, you should revise how Latin conveys the Comparative and Superlative

degrees of adjectives and adverbs.

BASIC ADJECTIVE / ADVERB That certainly is a fast, strong and ferocious

chicken!

COMPARATIVE I have never seen a faster, stronger, more ferocious chicken!

SUPERLATIVE That is the fastest, strongest, most ferocious chicken I have seen!

You must thoroughly revise the adjective and adverb tables which can be found at:

Palmer Latin Language pp. 144-145

or

Kennedy Revised Latin Primer pp. 41-44

When you are confident that you are familiar with adjectives and adverbs, follow this

link to the Adjectives and Adverbs self-assessment exercise.

Language: Week 4

Syntax Consolidation: Active Verbs

Before embarking upon advanced linguistic work, it is absolutely essential that you

ensure that your knowledge of basic Latin accidence is absolutely rock-solid.

This week, you should revise all the tenses of Active Indicative Verbs. You will need

to be able to recognise the tense and person of a Latin verb. Without a secure

knowledge of verbs you will find it very difficult to make progress in this subject.

You must thoroughly revise the active verb tables which can be found at:

Palmer Latin Language p. 154

or

Kennedy Revised Latin Primer pp. 62,64,66,68,70

When you are confident that you are familiar with active verb endings, follow this

link to the Active Verbs self-assessment exercise.

Language: Week 5

Syntax Consolidation: Passive Verbs

Before embarking upon advanced linguistic work, it is absolutely essential that you

ensure that your knowledge of basic Latin accidence is absolutely rock-solid.

3

This week, you should revise all the tenses of Passive Indicative Verbs.

You will need to be able to recognise the tense and person of a Latin verb. Without a

secure knowledge of verbs you will find it very difficult to make progress in this

subject.

You must thoroughly revise the active verb tables which can be found at:

Palmer Latin Language p. 156

or

Kennedy Revised Latin Primer pp. 72,74,76,78,80

When you are confident that you are familiar with passive verb endings, follow this

link to the Passive Verbs self-assessment exercise.

4

Language: Week 6

Direct Commands and Questions

Commands

Second person Direct Commands are expressed in Latin by the imperative:

Make sure you know how to recognise Active and Passive Imperatives!

Singular:

Plural:

ad me veni

duc eam ad carcerem!

audite hoc

sedete et tacete

- come to me

- lead her to prison

- hear this

- sit down and shut up!

For polite commands to a singular recipient, Latin might use fac (ut) or cura (ut) + present subjunctive:

cura ut scribas

- make sure that you write / be sure to write

Direct Prohibitions are expressed using noli / nolite followed by an Infinitive:

Singular:

noli lacrimare, Cornelia!

- don’t cry, Cornelia!

Plural:

nolite desperare, milites!

- don’t despair, men!

Non, Nemo, Numquam, Nihil are not used in commands:

noli quemquam mittere

- send no one - literally 'do not send anyone'

First and Third person Commands are expressed by the present (iussive) subjunctive (negative ne):

moriamur

ne exeant urbe

- let us die

- let them not go out of the city

5

Questions

Direct Questions are simple sentences in Latin.

If a question is asking for specific information, the sentence will begin with an interrogative (question word).

Some of the most common Latin interrogatives are:

qualis, -is, -e?

quantus, -a, -um?

quomodo?

quid?

qui, quae, quod?

quotiens?

quot?

uter, utra, utrum?

What sort of ...?

How big ...?

How ...?

What ...?

Which ...?

How often ...?

How many ...?

Which (of two) ...?

cur?

quare?

quis?

quando?

ubi?

quo?

unde?

Why ...?

Why ...?

Who ...?

When ...?

Where ...?

To where ...?

From where ...?

Questions which do not seek information but require an answer of 'yes' or 'no' are introduced by nonne (implying

the answer 'yes'), num (implying the answer 'no') or the suffix -ne (with no implication).

canis nonne similis lupo est?

num negare audes?

potesne dicere?

- isn't a dog like a wolf?

- do you dare to deny?

- can you say?

of course it is!

surely you don't!

yes or no)

N.B. - ne is added to the first word in the question.

In direct alternative questions, the first alternative is usually introduced by utrum (“whether”) and the second by

an, anne (both 'or') or annon ('or not'):

utrum pro servo me habes an servo? – do you regard me as a slave or a son?

isne est quem quaero annon? - is he the man I am seeking or not?

Deliberative questions occur when a character asks him or herself what course of action to pursue.

When people are “thinking out loud” in this way, they use the subjunctive mood in Latin.

Deliberative questions which debate what to do next are expressed with the present subjunctive; the imperfect

subjunctive is used to debate past actions:

quo me nunc vertam? - where am I now to turn?

quid faciam? - what am I to do?

nonne argentum redderem? – should I have given back the money?

num uxorem meam interficerem? – should I really have killed my wife?

6

Facienda

Translate into English:

nolite barbaris credere! a ducibus regimini! fortiter pugnate!

nolite quemquam mittere!

noli umquam huc venite!

vivat regina!

in hostem audacter festinemus!

quid cives eo tempore agerent?

potesne iudicare?

nonne Vergilius poeta summa calliditate est?

num dormire quam laborare mavultis?

quid nunc faciant? quo eant? nonne pecuniam reddant?

7

Language: Week 7

Infinitive and Indirect Statement

I: Use of Infinitives

The infinitive is the part of the verb which plays the part of a noun in its sentence. In

a Latin sentence an infinitive may act as a subject, object or complement.

• The infinitive is always a neuter noun; any qualifying adjectives must agree:

dulce et decorum est pro patria mori (Horace) - it is sweet and proper to die

for your country

• Some common verbs take an infinitive object

e.g.

possum, posse, potui - I am able

volo, velle, volui - I wish

soleo, solere, solitus sum - I am accustomed

timeo, timere, timui - I am afraid

conor, conari, conatus sum - I try

nolo, nolle, nolui - I do not want

malo, malle, malui - I prefer

linguam Latinam discere frustra conatus sum - I tried in vain to learn the Latin

language

• Other verbs take a person object and an infinitive object

e.g.

iubeo, iubere, iussi, iussum - I order

prohibeo. prohibere, prohibui - I prevent

veto, vetare, vetui, vetitum - I forbid, order...not

sino, sinere, sivi, situm - I allow (give permission)

patior, pati, passus sum - I allow (do not prevent)

cogo, cogere, coegi, coactum - I force, compel

pueros discedere prohibebant - they prevented the children from leaving

• An infinitive is used as the subject of a number of impersonal verbs and phrases

e.g.

(mihi) placet - it pleases me, I resolve

(me) iuvat - it pleases me

(mihi) mos est - it is my custom

(me) paenitet - I regret

(mihi) necesse est - it is necessary for me, I must

(me) pudet - I am ashamed

8

constat - it is agreed

manifestum est - it is plain

Romanis mos est barbaros opprimere - it is the custom of the Romans to crush

barbarians

• An infinitive is also used with:

paratus sum - I am ready

in animo habeo - I intend

Tenses of the Infinitive - very important!!

The Infinitive can be ACTIVE or PASSIVE in meaning, and can be PRESENT,

PERFECT or FUTURE.

Study the following table and ensure that you are familiar with the various forms of

the Infinitive (mitto is given as an example)

Present Infinitive

Active

Passive

-are, -ere, -ere, -ire

-ari, -eri, -i, -iri

mitti

mittere

to be sent

to send

Perfect Infinitive

Future Infinitive

perfect stem + -sse

misisse

past participle + esse

missus esse

to have sent

to have been sent

future participle + esse

missurus esse

supine + iri

missum iri

to be about to send

to be about to be sent

Facienda

bene vivere, fortiter mori: haec sapientis sunt

turpe est a mercatoribus decipi

solent diu cogitare qui volunt magna facere

9

non poteram magistro meo respondere

plurimi malunt ludos spectare quam laborare

Agricola suos iussit in Caledoniam progredi

pater te non sinet opera Catulli legere

Caesari placuit castra ponere

mos est Germanis etiam templa munire

me non paenitebat erravisse

10

Language: Week 8

Infinitive and Indirect Statement

II: Indirect Statement

(after verbs of saying, thinking, knowing, believing and feeling)

In English, direct speech is reported in a subordinate clause introduced by that and

having a finite verb.

Direct: “The king is a cruel man”

Indirect: He says/thinks/knows that the king is a cruel man.

Latin places the subject of the direct speech into the accusative case and the verb into

the infinitive.

Direct: “rex est crudelis”

Indirect: dicit / arbitratur / scit regem crudelem esse

Tenses of the infinitive

The tenses of the Latin infinitive do not indicate time absolutely, but only in relation

to the verb on which they depend.

The present infinitive indicates a contemporary action (same time)

The perfect infinitive indicates a prior action (past)

The future infinitive a subsequent action (future).

The table below summarises the forms of the various tenses of the infinitive:

Active

Passive

Present

Infinitive

-are, -ere, -ere, -ire

mittere, audire

-ari, -eri, -i, -iri

mitti, audiri

Perfect

Infinitive

perfect stem + -sse

misisse, audivisse

past participle + esse

missus esse, auditus esse

Future

Infinitive

future participle + esse

missurus esse, auditurus esse

supine + iri

missum iri, auditum iri

Verbs without future infinitives

Some active verbs have no future infinitive (e.g. possum); Latin must then use a

periphrastic construction consisting of futurum esse ut or fore ut + the present or

imperfect subjunctive of the verb concerned:

e.g. dico futurum esse (fore) ut possim - I say that I will be able

11

This periphrastic construction is also frequently used as an alternative to the future

passive infinitive (supine + iri).:

nuntiavit futurum esse ut oppidum mox caperetur

nuntiavit oppidum mox captum iri

- He reported that the town would soon be captured.

The table below gives examples of the sequence of infinitives in indirect statement.

Note that the tense of the introductory verb of saying, thinking etc. does not in itself

affect the tense of the infinitive.

dico

eum venire

eum venisse

eum venturum esse

I say

that he is coming

that he has come

that he will come

copias mitti

copias missas esse

copias missum iri

that forces are being

sent

that forces have been

sent

that forces will be sent

dixi

eum venire

eum venisse

eum venturum esse

I said

that he was coming

that he had come

that he would come

copias mitti

copias missas esse

copias missum iri

that forces were being

sent

that forces had been

sent

that forces would be sent

Note from the bold type that the participial elements of the infinitive must agree with

the accusative subject of the indirect speech.

• He, she, they in indirect speech must be translated by the reflexive pronoun se

whenever one of these pronouns stands for the SAME person as the subject of the

verb of saying or thinking; the reflexive possessive pronoun suus is also used if his,

her or their refers to the speaker:

scit se bene laboravisse

- he knows that he (i.e. himself) has worked well.

affirmaverunt se in patriam suam redituros esse

- they declared that they would return to their own land.

• If the second he, she, they refers to somebody ELSE, the proper part of is or ille

must be used. In that case, any possessive pronoun must be translated by eius or

eorum:

putat eum bene laboravisse

- he thinks that he (somebody else) has worked well.

12

affirmaverunt eos in patriam eorum redituros esse

- they declared that they would return to their own land.

(Remember: SE refers to the SUBJECT; EIUS refers to somebody ELSE)

• I say that... not is never translated by 'dico... non...' Instead, Latin uses the verb nego

(I deny)

negavimus nos hoc umquam fecisse

- we deny ever having done this

• VERY IMPORTANT!!

Verbs of hoping, promising, swearing and threatening generally (by the nature of

hopes, promises, oaths and threats) require accusative and future infinitive:

pollicebatur pecuniam se esse redditurum

- he kept on promising to return the money

Facienda

1. audio Marcum aegrotare

2. heri comprehendi Marcum aegrotare

3. satis constat Romulum urbem Romam condidisse

4. credidi me sonum audivisse

5. scimus amicam nobis epistulam missuram esse

6. promiserunt classem mox adventuram esse

7. num affirmas oppidum oppugnari?

8. legatus negavit copias mitti

9. ferunt coniuratos media nocte trucidatos esse

10. nuntiaverant naves a Romanis incensas esse

11. spero me rem bene gessurum esse

13

12. imperatores promittebant hostes victum iri

13. affirmaverunt se in patriam suam redituros esse

14. minatus est se pecuniam numquam redditurum esse

15. his dictis Caesar promisit fore ut castra hostium caperetur

16. pro certo habeo fore ut consules fiamus

17. legimus Nerone regnante Urbem incendio deletam esse

18. liberaberis si promiseris te praedam reddituram esse

19. custodes affirmaverunt neminem arcem intrare conatum esse

20. pro certo habeo me nimis vini bibisse

14

Language: Week 9

Participles

The participle is the part of the verb which plays the part of an adjective

Latin verbs generally have three participles:

present (e.g. amans, goes like ingens)

perfect (amatus -a –um goes like bonus)

and future (amaturus -a -um)

They most often form a substitute for a subordinate clause, and frequently are used

with a finite verb where English uses two verbs joined by and - Latin doesn't like two

main verbs in one sentence.

• The present participle is used to connect two simultaneous actions:

flumen transiens, puer de ponte decidit

- (while) crossing the river the boy fell from the bridge

• The perfect participle is used if one action follows the other:

flumen transgressus, puer urbem intravit

- (after) crossing the river the boy entered the city

• ONLY DEPONENT VERBS have perfect participles which are active in meaning:

haec locutus aciem instruxit

- having spoken in this way he drew up his battle-line

milites celeriter progressi portas oppugnaverunt

- having advanced swiftly the soldiers stormed the gates

• Otherwise the perfect participle is always PASSIVE in meaning (auditus never

means 'having heard')

captivi ab hostibus liberati domum regressi sunt

- having been released by the enemy the captives returned home

• The future participle has an ACTIVE meaning (e.g. scripturus - 'about / going to

write'). It is most usually coupled with a tense of sum to form periphrastic tenses

(locuturus eram - I was about to speak)

Participles may also be used as adjectives:

homo sapiens, canis fidens, mulieres eruditae etc.

or as nouns: praefectus - commander, facta – deeds etc.)

15

- and perhaps most famously 'morituri te salutant' - those who are about to die salute

you

Participial expressions of time

Participial constructions are often used in place of temporal clauses

So, postquam haec dixit, abiit could alternatively be written:

haec locutus abiit (past participle, deponent verb)

or his dictis abiit (ablative absolute construction)

The ABLATIVE ABSOLUTE (a phrase consisting of a noun in the ablative case and

a participle, or another noun or adjective, in agreement with it) very frequently carries

a temporal meaning.

A full explanation of this construction will be given in next week’s Language note on

the Ablative Case.

Facienda

hanc epistulam scribens paene obdormivi

gladium meum consuli ad mortem eunti dedi

equites, Gallos victos secuti, castra eorum ceperunt

urbem oppugnaturi constitimus

latrones sacra e templis urbis incensae abstulerunt

Graeci Troiam diu obsessam multis occisis ceperunt

uxor me tuas epistulas legentem in hortum vocavit

postea Britanni, qui Romanis odio erant, libertatem recipere numquam conaturi erant

Language: Week 10

16

The Ablative Case

The Ablative Case is the fifth and last of the major noun cases in Latin. Traditionally

it is said to mean “by, with or from”, but it is in reality far more versatile than this.

The Ablative Case is the “dustbin case” which collects all the other functions which

are not shared by the other cases.

Ablatives after a Preposition

Most frequently you will encounter the Ablative Case after prepositions. There are

too many preposition + Ablative combinations to be listed here, and you will need to

be aware of then and their meanings. Here are just a few:

heri cum amicis meis cenabam

- Yesterday I had dinner with my friends

latrones in montibus latebant

- The robbers were lying hidden in the mountains

me de clade sua certiorem fecit

- He told me about his disaster

ex urbe effugit

- He fled from the city

Most important in this section is the Ablative of Agent, where the person or animal

by whom something is done is expressed by the preposition a (or ab if the next word

starts with a vowel) followed by the Ablative Case:

Caesar a Bruto necatus est

- Caesar was murdered by Brutus

sacerdos, ab avibus sacris oppressus, pugionem deiecit

- The priest, having been attacked by the sacred birds, threw down his dagger

The Ablative has many further uses in Latin which do not require the presence of a

Preposition which you will encounter in Unseen Translation and set text preparation.

You will need to be aware of the range of possible functions, and apply this

knowledge in order to deduce the most likely outcome.

Remember:

Knowledge + Common Sense = Success in Latin!

Functions of the Ablative without prepositions

17

Ablative of Instrument

This expresses the thing (an inanimate object, as opposed to a person or animal) by

which something is done:

alii saxis cadentibus, alii frigore interfecti sunt

- Some were killed by falling rocks, others by the cold

Caesar, pugione percussus, humi cecidit

- Caesar fell to the floor, struck by a dagger

rex fratrem suum veneno necaverat

- The king had killed his brother with poison

Ablative of Manner

This specifies the manner in which something is done:

magna cura atque diligentia scripsit

- He wrote with great care and attention

fures cubiculum tacitis vestigiis ingressi sunt

- The thieves entered the bedroom with silent footsteps

Ablative of Cause

This is most frequently used with adjectives, passive participles and verbs which

denote a mental state or emotion:

coeptis immanibus effera Dido

- Dido, driven mad by her terrible undertakings

fratres, metu pallidi, immoti stabant

- The brothers stood motionless, pale from fear

Ablative of Separation

Used with verbs and adjectives which mean keep away from, free from, deprive, lack,

and after the adverb procul (far from)

beatus ille qui procul negotiis, solutus omni faenore

Blessed is the man who, far from business affairs and free from all debt

nemo eos isto carcere liberare poterat

Nobody could free them from that prison

18

Ablative of Comparison

There are two ways of expressing comparison in Latin.

• One is to use quam

incolae illius regionis pugnaciores sunt quam Britanni

The inhabitants of that region are more warlike than the British

• The other is to create a direct comparison by using the Ablative case:

incolae illius regionis Britannis pugnaciores sunt

The inhabitants of that region are more warlike than the British

nihil est amabilius virtute

Nothing is more worthy of love than virtue

Ablative of Measure of Difference

Used when you specify how much bigger, faster, stronger (etc.) one thing is than

another:

puella multo tristior quam antea fiebat

The girl was becoming much sadder than before

quo plus habent, eo plus cupiunt

The more they have, the more they desire

leo paulo minor erat quam equus

The lion was a little smaller than a horse

The Ablative of Measure of Difference is also used after ante or post to specify how

long before or after something occurred:

decem ante annis - ten years earlier

multis post diebus - many days later

Ablative of Description / Ablative of Quality

This is used in agreement with a noun to provide a description

senem promissa barba, horrenti capillo conspexit

He spotted an old man with a long beard and unkempt hair

Aeneas adhuc incerto animo erat

Aeneas was still uncertain in his mind

19

Ablative of “Time When”

The TIME WHEN something happens is expressed by the ablative case without

preposition of nouns which in themselves denote time.

vere - in spring

solis occasu - at sunset

eo anno - in that year

ego Capuam eo die adveni - I arrived at Capua on that day

Ablative of “Time within which”

The TIME WITHIN WHICH something occurs is also expressed by the ablative

without preposition.

brevi tempore - in a short time

quicquid est biduo sciemus - whatever it is, we shall know in (= within) two days.

This function of the Ablative is also used in negative sentences to express duration of

time:

eum multis diebus non vidi - I haven't seen him for many days.

A few verbs and adjectives also take an Ablative object

utor, usi, usus sum

+ ABL

use

fruor, frui, fructus sum

+ ABL

enjoy

fungor, fungi, functus sum

+ ABL

perform

potior, potiri, potitus sum

+ ABL

acquire, get possession of

careo, carere, carui

+ ABL

lack

egeo, egere, egui

+ ABL or GEN

lack

dignus, -a, -um

+ ABL

worthy of

fretus, -a, -um

+ ABL

relying on

orbus, -a, -um

+ ABL

deprived of

praetitus, -a, -um

+ ABL

endowed with

plenus, -a, um

+ ABL or GEN

full of

20

Ablative Absolute

An ABLATIVE ABSOLUTE phrase consists of a noun in the Ablative case and a

participle (or another noun or adjective), in agreement with it.

Most frequently the Ablative Absolute will be found at the start of the sentence,

taking the place of a cum clause, although it could be encountered anywhere in a

sentence:

duce vivente nobis adhuc spes erat

- while the general was alive we still had hope

consulibus Cicerone et Antonio templum Iovis incendebatur

- when Cicero and Antonius were consuls the temple of Jove was set on fire

urbe capta imperator obsides opesque postulavit

- when the city had been captured the commander demanded hostages and money

regibus exactis consules creati sunt

- after the kings had been expelled, consuls were created

Catilinam te repugnante accusabo

I will prosecute Catiline in spite of your resistance

BUT the Ablative Absolute construction may only be used if the noun within it has no

grammatical connection with the main sentence (absolutus = 'set free'). If there is a

grammatical connection, then another case of the participle is used.

Ablative Absolute:

milites litteris acceptis castra hostium oppugnaverunt

When the letter had been received, the soldiers attacked the enemy's camp

No Ablative Absolute:

milites litteras acceptas legerunt

The soldiers, when they had received the letter, read it

haec legens te conspexi

While I was reading this I saw you

Facienda

21

navem prima luce solvam

brevi tempore Romam adveniemus

multis vulneribus iam acceptis, suos hortatus est ut fortiter perirent

media nocte Romani demum arce potiti sunt

Graeci Troiam diu obsessam multis occisis ceperunt

quinque post mensibus quam consul creatus est, morbo affectus est

nesciebam utrum morbo an pavore pallidae essent

uxore filiisque a fugitivis necatis, vino somnioque abstinebat dum eos ulcisceretur

credo Lucilium, virum summa virtute, patre multo eloquentiorem facturum esse

metu deposito, silvam densam intravimus ut nos celaremus

22

Language: Week 11

Genitive Case, Dative Uses and Predicative Dative

1. Genitive Case

The Genitive Case is another of the major noun cases in Latin. Most frequently it

denotes Possession, informing you to whom or to what something belongs, and means

“of”:

copiae regis - the forces of the king / the king’s forces

virtus hominis est robur reipublicae - a man’s courage is the state’s strength

However, in reality the Genitive Case is rather more versatile than this.

Genitives of Definition

• Defining another noun:

artem scribendi numquam cognovi - I have never learned the art of writing

Romani nomen regis oderunt - The Romans hate the name of “king”

• Defining the content of something, or the material of which it is made:

acervus frumenti - a pile of corn

• Defining the fault or crime of which somebody is accused, convicted or acquitted:

alter latrocinii reus, alter caedis convictus est - The first was accused of robbery, the

second was convicted of murder

Severus, proditionis absolutus, ex urbe effugit - Severus, acquitted of treason, fled the

city

Genitive of Quality or Description

This is used in agreement with a noun to provide a description. Number, age and size

are expressed by this kind of Genitive:

vir summae virtutis ingenuique pudoris - a man of the highest good character and

noble modesty

classis septuaginta navium - a fleet of seventy ships

olim senem centum annorum vidi - I once saw an old man who was 100 years old

23

Genitive of Value

When a general value is given to something (a personal opinion of value, not a precise

cost), the following Genitives are used:

magni

tanti

parvi

quanti

plurimi

pluris

minimi

miniris

nihili

voluptatem sapiens minimi facit

- the wise man considers pleasure to have very little value

nullam possessionem pluris quam virtus aestimabat

- He regarded no possession to be more precious than virtue

Partitive Genitive

The Genitive of a noun of which a part is mentioned:

sic partem maiorem copiarum Antonius amisit

In this way Antony lost the greater part of his forces

totius Graeciae Plato doctissimus erat

Plato was the most learned man of all Greece

Catinina satis eloquentiae, parum sapientiae possidebat

Catiline had enough eloquence, but too little wisdom

olim tria milia hostium occidi!

I once killed three thousand of the enemy!

credo me nimis vini consumpsisse!

I think I’ve drunk too much wine!

Genitives with Verbs and Adjectives

A number of Verbs and Adjectives take a Genitive object, or are frequently used with

the Genitive:

potior, potiri, potitus sum

+ GEN or ABL

acquire, get possession of

egeo, egere, egui

+ GEN or ABL

lack

indigeo, indigere, indigui

+ GEN

need, require

impleo, implere, implevi

+ GEN

fill

plenus, -a, um

+ GEN or ABL

full of

memini, meminisse

+ GEN

remember

obliviscor, oblivisci, oblitus sum

+ GEN

forget

memor

+ GEN

mindful of

24

immemor

+ GEN

forgetful of

misereor, misereri, miseritus sum

+ GEN

pity

Some Impersonal Verbs which convey feelings take an Accusative of the person who

feels the feeling, together with the Genitive of whatever is causing the feeling:

miseret

+ ACC

+ GEN

pity

piget

+ ACC

+ GEN

annoyance

paenitet

+ ACC

+ GEN

regret

pudet

+ ACC

+ GEN

shame

taedet

+ ACC

+ GEN

tiredness

me pudet paenitetque facinoris - I am ashamed of and regret my crime

There are no FACIENDA exercises this week.

You are probably most familiar with the idea of the Dative Case being the case which

shows TO WHOM something is given or FOR WHOM something is done.

Unfortunately, Latin is not that straightforward!

Read through the following notes on the DATIVE case, study the examples given,

and translate the sentences in the “Facienda” sections.

2. Dative uses

• The Dative of the Indirect Object is the most familiar use of the Dative Case in

Latin. It is used with verbs of giving, telling, showing, saying and promising.

mihi fabulam mirabilem narra; ego tibi librum pretiosum ostendam

- tell me a wonderful story; I will show you an expensive book

• The Dative Case also follows adjectives which imply nearness, likeness, help,

kindness, trust, obedience, fitness or any opposite idea

homini fidelissimi sunt equus et canis

- the horse and dog are the most faithful animals to man

25

• The Dative of Advantage tells you the person (or thing) to whose advantage

something is done

mater filio donum quaerebat

- Mother was looking for a present for her son

• A Dative Indirect Object (Dative of Disadvantage) is also used with verbs of taking

away, where the word from would be used in English. The verbs concerned are aufero

(I remove), adimo (I take away), eripio (I snatch away, rescue)

heros filiam pulchram latronibus eripuit

- the hero rescued the beautiful girl from the robbers

• A Dative of Purpose is used with some verbs, especially those meaning choose or

appoint, to express the end in view

Caesar munitioni castrorum tempus reliquit

- Caesar left time for fortifying the camp

dies colloquio constituta est

- a day was chosen for the meeting

3. Dative objects of verbs

Some transitive verbs in English are translated by intransitive verbs in Latin (i.e. they

govern an indirect (dative) object instead of a direct (accusative) object). You will

need to get to know which verbs take dative objects...

The most frequent verbs of this kind are:

• Many verbs of aiding (auxilior, subvenio), favouring (faveo, studeo), obeying

(pareo, obsequor), pleasing (placeo), serving (servio)

sic agam, ut magistro meo placet

- I will act in such a way as pleases my teacher

• Verbs of injuring (noceo), opposing (adversor, obsto, repugno), displeasing

(displiceo)

haec res omnibus hominibus nocet

- this state of affairs harms all men

26

gallinae nobis obstant in via stantes

- the chickens hinder us (get in our way) by standing in the road

• Verbs of commanding (impero, praecipio), persuading (suadeo, persuadeo),

trusting (fido, credo), distrusting (diffido), sparing (parco), pardoning (ignosco),

envying (invideo), being angry (irascor)

victis victor pepercit

- the conqueror spared the defeated

virtuti suorum credebat; sibi tamen irascebat

- he trusted the courage of his men, but he was angry with himself

• Most compounds of sum govern a dative

(exceptions to this rule: possum, absum, insum)

nuptiis adsumus - we are present at the wedding

his rebus non interfuimus - we did not take part in these events

omnibus Druidibus praeest unus - one man is in command of all the Druids

Facienda I

Caesar genti isti bellum intulit, quod provinciae nocuerant

respondi neminem fere ei iam favere; illi autem noluerunt mihi credere

ars mea mihi prodest; pecunia tamen mihi deest

4. Passive of intransitive verbs

Unlike English, Latin can use the passive voice of intransitive verbs, but only

impersonally, that is, in the THIRD PERSON SINGULAR FORM without a

nominative subject at all. (The word which should be taken as the subject of the

English sentence will often be in the Dative case in Latin).

qui invident egent, illis quibus invidetur, i rem habent

- people who are envious are in need; but those who are envied have the stuff

If a participle forms part of an impersonal verb, it is always neuter and singular:

27

nobis ab amicis aegre persuasum est

- we were barely persuaded by our friends

Note here that, as the verb persuadeo is intransitive in Latin (it takes a Dative object),

it automatically reverts to the third person singular form when turned Passive, and the

person or persons being persuaded go into the Dative case.

The idea of impersonal passives is often to focus attention on the action, as the

person(s) doing the action is too vague or too obvious to mention.

Note the idioms (most commonly from the verbs eo, venio, curro, clamo, pugno):

sic itur ad astra - that is the way to the stars

postquam ventum est - after (our) arrival

Facienda II

acriter pugnatum est dum nox advenit

nobis ad urbem quinto die perventum est

Gallis a legionibus nostris parcetur, quamquam nobis tam diu restiterunt

5. Predicative Dative

The verb esse (to be, to serve as) sometimes has as its complement a noun in the

dative case: this is called the Predicative Dative. The expressions which involve a

predicative dative construction vary, e.g.:

auxilio esse - to be helpful

curae esse - to be an anxiety

praesidio esse - to protect (etc.)

subsidio esse - to support,relieve

impedimento esse - to hinder

cordi esse - to be dear

usui esse - to be useful

oneri esse - to be a burden

exitio esse - to be fatal

dedecori esse - to be disgraceful

documento esse - to be proof

detrimento esse - to cause loss

• The Predicative Dative is usually accompanied by another dative indicating the

person affected (dative of advantage).

28

senectus mihi impedimento est

- old age is a hindrance to me (in effect impedimento means 'a source of hindrance,

something serving as a hindrance')

• A Predicative Dative is always singular, and cannot be qualified by an adjective,

except an adjective of quantity or size (magnus, maximus, quantus, tantus).

illud omnibus magno usui erat - that was of great use to everybody

incolae nobis minimae curae sunt - the inhabitants are of the least anxiety to us

• The predicative dative may also be used after verbs like habeo (I consider as), duco

(I reckon as), eligo (I choose as), and (in military language) after verbs meaning

come, go, send, leave.

habere quaestui rem publicam turpe est - it is disgraceful to treat the state as a

source of gain.

dono dare - to give as a present

unam cohortem castris praesidio reliquit - he left one cohort to garrison / guard the

camp

The verb odi, odisse (to hate) has no passive. Latin instead uses odio esse + Dative (to

be hateful to).

gladiatores omnibus civibus odio sunt - Gladiators are hated by all citizens

Facienda III

hoc Lepido dedecori magno erat

tempestas hostibus exitio, classi nostrae saluti erat

cur Antonius odio erat omnibus, quibus libertas cordi erat?

auxilia dexterae alae subsidio venerunt

mulieres puerosque oppido praesidio elegerunt

prudentia maiorum nobis exemplo semper sit!

29

Language: Week 12

Relative Clauses

Relative Clauses are clauses which give more information about the noun to which

they refer (called the antecedent)

The Relative Pronoun, which introduces these clauses, agrees in number and gender

with the noun it describes.

The case of the Relative Pronoun depends on its function within its own clause:

ancillae, quae totum diem laboraverant, defessae erant

The slave-girls, who had worked all day, were exhausted

The Relative Pronoun (quae) is feminine and plural, because it refers to ancillae; it is

nominative, because the slave-girls are the subject of laborabant.

ancillae, quas dominus in Britannia emerat, pulcherrimae erant

The slave-girls, whom the master had bought in Britain, were very beautiful

The Relative Pronoun (quas) is feminine and plural again, referring back to ancillae.

But this time it is accusative, because the slave-girls are the object of emerat.

Here are the forms of the Relative Pronoun in Latin:

SINGULAR

PLURAL

masculine

feminine

neuter

masculine

feminine

neuter

qui

quae

quod

NOMINATIVE

qui

quae

quae

quem

quam

quod

ACCUSATIVE

quos

quas

quae

cuius

cuius

cuius

GENITIVE

quorum

quarum

quorum

cui

cui

cui

DATIVE

quibus

quibus

quibus

quo

qua

quo

ABLATIVE

quibus

quibus

quibus

Facienda I

Itandem nautae, qui magnis tempestatibus impediti erant, ad portum incolumes

pervenerunt

praemium, quod promiserat, mihi dare noluit

nonne puellam vides, cuius pater a latronibus captus est?

mercatorem, cui pecuniam dedisti, interficere volo

30

Further Uses of Relative Clauses

1. LINKING QUI

At the beginning of a sentence, a Relative Pronoun may be used to link to the

previous sentence. Under these circumstances, do not translate as “who” or “which”:

Caesar equites statim emisit. qui cum proelium commisissent, hostes terga verterunt

Caesar sent out cavalry at once. When they had joined battle, the enemy turned and

fled

Some other common linking phrases (really useful to learn!):

quo cognito… When this had been found out…

quibus cognitis… When these things had come to light…

quo facto… This done…

quibus factis When these things had been done…

quo dicto… Having said this / When this had been said…

quibus dictis… When these things had been said / After saying these things…

2. RELATIVE CLAUSES OF PURPOSE AND RESULT

• If the verb in the Relative Clause is subjunctive, the idea is often one of Purpose:

legatos misit qui nuntiarent Brutum advenisse

He sent envoys to report (= who were to report) that Brutus had arrived

• The Relative Pronoun can also appear in Result Clauses:

non eram tam stultus qui fratri crederem

I wasn’t so stupid as to trust my brother

• The following phrases are also followed by subjunctive verbs, and are types of

Result Clause:

quippe qui… in that he…

dignus qui… worthy to…

is qui… the kind of person who…

sunt qui… there are those who…

sunt qui Romanos non ament

There are those who do not love the Romans

31

Caesar non erat is qui periculum timeret

Caesar was not the kind of man to fear danger

Facienda II

quo facto, speculatores praemissi sunt qui silvas explorarent

quibus dictis, servo pecuniam dedit qua panem vinumque emeret

filia tua non est digna quae mihi nubeat

erant permulti qui Caesaris verbis non crederent

32

Language: Week 13

Subjunctive Verbs and Independent Subjunctives

Before embarking upon advanced linguistic work, it is absolutely essential to ensure

that your knowledge of basic Latin accidence is absolutely rock-solid.

This week, you should revise all the tenses of Subjunctive Verbs.

You will need to be able to recognise the tense and person of a Latin verb. Without a

secure knowledge of verbs you will find it very difficult to make progress in this

subject.

You must thoroughly revise the active verb tables which can be found at:

Palmer Latin Language pp. 155 and 157

or

Kennedy Revised Latin Primer pp. 63, 65, 67, 69, 71, 73, 75, 77, 79, 81

Many of the patterns of subjunctive verbs are very distinctive, and you should have

little trouble in recognising them.

THEN study how Subjunctive verbs are used as the main verb in a Latin sentence:

Independent Subjunctives

Jussive, Optative, Deliberative, Potential

• Jussive Subjunctives are used mainly in 1st and 3rd person direct commands and

prohibitions in the present subjunctive (negative ne); sometimes ne + perfect

subjunctive is used for 2nd person prohibitions:

fugiant ignavi - let the cowards run away

fortiter moriamur - let us die bravely

milites neve culpent neve contemnant ducem

- let the soldiers neither blame nor despise their general

• Optative Subjunctives express a wish, desire or prayer. These wishes are very

often introduced by utinam, or by utinam ne if the wish is negative. (Negative wishes

must always include ne).

Tense rules:

The PRESENT subjunctive introduces a wish for the future

The IMPERFECT subjunctive introduces a wish for present time (wishes that

something should be so now)

The PLUPERFECT subjunctive introduces a wish for the past (wishes that something

had happened)

33

utinam veniant - if only they would come!

(refers to the future, therefore present subj.)

utinam Cicero adesset - if only Cicero were here!

(now, therefore imperfect subj.)

utinam ne quid dixissetis - I wish you (pl.) hadn't said anything!

(in the past; pluperfect subj.)

• Deliberative Subjunctives are used, most often in deliberative questions, to discuss

possible courses of action: what ought to be done. The PRESENT SUBJUNCTIVE

is used to refer to (present and) future times, the IMPERFECT SUBJUNCTIVE to

the past. NOTE that the negative of this type of subjunctive is non. utrum... an may

introduce alternative deliberatives.

quo me nunc vertam? quid faciam?

- Where am I now to turn? What am I to do?

quomodo exploratores insidias vitarent?

- How were the scouts to avoid the ambush?

nonne argentum redderem? non redderes

- Should I have returned the money? You should not

• Potential Subjunctives express what would happen or might have happened under

certain circumstances. One verbal activity is dependent on the fulfilment of another

(which either hasn't or won't happen yet). The tense rule is the same as that given for

Optative Subjunctives above.

Subjunctives of this sort often occur in Conditional Sentences:

si esset in terris, rideret Democritus

- If Democritus were on earth, he would be laughing

But, by suppressing the condition necessary to fulfil this condition, the same potential

idea may be expressed

quid tu tum fecisses? - What would you have done then?

hoc tu dicere audeas? - Would you dare to say this?

The most common Potential Subjunctives are velim/vellem, nolim/nollem, and

malim/mallem.

They govern an infinitive (I should like to go - velim ire) if there is no change of

subject, but if there is (e.g. I should like you to go) they are followed directly by an

optative subjunctive (without ut or any other conjunction). They basically introduce

wishes that cannot be or have not been fulfilled:

wish for the future:

nolim tam felices sint - I (could) wish they wouldn't be so lucky

34

wish for the present:

velim adesses - I wish you were here

wish for the past:

mallem abissent - I would rather they had gone (i.e. it is too late)

vellem adesse posset Paenaetius – I wish Panaetius could be present

vellem me ad cenam invitasses - I wish you had invited me to dinner

(This construction amounts to little more than a polite expression of volo; cf. French

“je voudrais”)

Take note of these Potential subjunctives:

crederes / putares - you would have thought... / you would think

diceres - you would have said... / you would say

These potential subjunctives are prime candidates for introducing indirect statements:

nihil respondit: putares eum non audivisse

- He made no reply: you would have thought he had not heard

Facienda

summa virtute pereamus; cives ne umquam dicent nos terga in hostes vertisse

utinam haberemus satis cibi aquaeque ut supersimus

utinam ne patres nostri in servitudinem coacti essent; liberi nostri quoque servi

infestorum Romanorum erunt.

cum patrem meum mortuum invenissem, quid agerem, iudices?

quotiens obsides a Romanis captos easdem contumelias parerentur?

velim Romam ire ut Aram Pacis videam; malim autem mecum venias

nautae in litore immoti iacebat; putares eos mortuos esse

quo confugiamus? utinam patriam haberemus quo eamus

35

Language: Week 14

Indirect (Reported) Commands, Exhortations and Purpose Clauses

In a narrative text, Latin authors rarely used direct speech. Instead, all acts of speech

(including statements, commands and questions) are expressed by Indirect

constructions. We have already studied Indirect Statements – we are now going to

look at Indirect Commands.

The umbrella term 'commands' includes requests, advice, acts of persuasion,

encouragement and so on. There are two possible constructions, the choice of which

will depend upon the choice of main verb.

1. Accusative and Infinitive

iubeo (I order)

veto (I forbid)

sino (I allow)

prohibeo (I prevent)

After these main verbs, the recipient of the order is put into the accusative case and

the order into the infinitive:

te ire veto - I am ordering you not to go

eum discedere sivi - I let him leave

Facienda I

Imagister nos iussit diligenter laborare

te veto hos libros scelestissimos legere!

2. Noun clause

All other verbs of commanding introduce clauses containing a subjunctive verb. The

Indirect Command construction consists of:

• An introductory verb

Some likely suspects:

impero – I order

rogo – I ask

praecipio – I instruct

persuadeo – I persuade

36

oro – I beg

hortor – I urge

invito – I invite

moneo – I warn, advise

• The word ut in a positive command, or ne in a prohibition

• A subjunctive verb (either present or imperfect subjunctive)

Present Subjunctive after a Primary Sequence main verb

Imperfect Subjunctive in Historic Sequence

Sequence of tenses

A sentence is in primary sequence if its main verb is in one of the following tenses:

Present, Future, Future Perfect, Perfect (meaning 'I have ...-ed only)

A sentence is in historic sequence if its main verb is in one of the following tenses:

Imperfect, Pluperfect, Perfect.

Examples:

(Primary Sequence)

nos hortatur ne cedamus

he exhorts us not to yield

(Historic / Secondary Sequence)

amicos oravit ut manerent

he begged his friends to stay

As in indirect statements, se and suus are used to refer back to the speaker of the

command:

avunculus me rogavit ut secum irem

my uncle asked me to go with him

Facienda II

tyrannum etiam atque etiam oramus ut mulieribus parcat

argentarius servis imperavit ut cenam pararent

pater mihi imperavit ne flumen appropinquarem; nonne ei paream?

eos hortatus sum ut confiterentur se arma contra nos sumpsisse

Varro Minucium admonuerat ne hostes duce absente oppugnaret

37

fratres a me petunt ut te doceam eos nolle fundum vendere

Purpose Clauses

(also called Final Clauses)

The purpose or aim of the action described in the principal clause, expressed in

English by a phrase or a clause (e.g. "I've been to London to see the queen") is

expressed in Latin by a Purpose Clause.

Purpose clauses are introduced by ut ('so that') or by ne ('so that... not', 'lest') if the

purpose of the principal action is negative.

The verb in the purpose clause is present subjunctive in primary sequence,

imperfect subjunctive in historic sequence.

multi alios laudant, ut ab illis laudentur

many men praise others so that they may be praised by them

gladium rapui ut captivum interficerem

I seized a sword in order to kill the prisoner

fur vestimenta atra gerebat ne conspiceretur

The thief wore dark clothes so as not to be seen

As a purpose clause reflects a thought or idea in somebody's mind, se and suus are

used reflexively in purpose clauses to refer to the thinker (as in indirect statement).

iudicibus praemia dedit ut se absolverent he gave the jurors bribes so that they would acquit him

Relative Clauses of Purpose

A positive purpose may be expressed by a RELATIVE CLAUSE introduced by the

appropriate form of the relative pronoun qui instead of ut. This construction is

especially common when the main verb means 'send', 'choose' or 'leave':

Clusini legatos Romam, qui auxilium a senatu peterent, miserunt

the Clusini sent ambassadors to Rome to seek aid from the senate

librum mihi dedit quem legerem

he gave me a book (which I was) to read

nullam pecuniam habeo qua cibum emam

I have no money with which to buy food

If a purpose clause contains a comparative word, it is introduced by quo, followed

immediately by the comparative word (quo is ablative of measure of difference 'by

which the more').

38

castella communit quo facilius eos prohibere possit (Caesar)

he strengthens the forts in order that he might keep them off more easily

Facienda

poeta Athenas iter faciet ut templa pulcherrima spectet

milites quam fortissime pugnabant ne aquilas ammitterent

exploratores pontem refregerunt ne hostes se sequerentur

Augustus custodibus suis praemia dabat quo carius se amarent

Caesar mulieres relinquet quae oppidum custodiant

piratae in portum navigaverunt ut naves nostras incenderent.

Hannibal venenum sumpsit ne a Romanis caperetur

viginti milia civium convenerant qui munera spectarent

39

Language: Week 15

Result Clauses

(also called Consecutive Clauses)

Result clauses define the consequence of what is stated in the principal sentence. They

are introduced by ut and contain a verb in the subjunctive mood. Since result clauses

express events rather than ideas, they do not follow the usual rules for sequence of

tenses - an event in the past (historic sequence) may have consequences in the present

or future (primary sequence). Broadly speaking, the tense of the subjunctive used will

be the same as one would expect if it were an indicative sentence, so translate what

you see!

I was tired + I slept for a long time

= I was so tired that I slept for a long time

defessus eram + diu dormivi

= tam defessus eram ut diu dormiverim (perfect subjunctive)

in Lucullo tanta prudentia fuit ut hodie stet Asia Luculli institutis servandis

Lucullus possessed so much foresight that Asia stands today by preserving his

arrangements

tanta fuit pestis ut permulti quotidie perirent, rex ipse morbo absumptus sit

So great was the plague that many were dying each day, and the king himself was

killed by the disease

The main clause usually contains a demonstrative adverb or adjective as a 'signpost',

such as:

tam - so, to such an extent

adeo - to such an extent

sic - in such a way

ita - in such a way

tot - so many

talis - of such a kind

tantopere - to such an extent

eiusmodi - of such a kind

tantus -a -um - so great

is/ea - of such a kind (usu. with qui, see below)

A result clause is made negative by ut... non...

tanta fuit viri moderatio ut repugnanti mihi non irasceretur

The man's self-control was so great that he was not angry with me when I opposed

him

Consequently the following differences between negative purpose and negative result

clauses are most important:

40

Purpose

Result

That not

ne

ut non

That nobody

ne quis

ut nemo

That nothing

ne quid

ut nihil

That no....

ne ullus

ut nullus

That never

ne umquam

ut numquam

That nowhere

ne usquam

ut nusquam

Contrast the following purpose and result clauses:

portae clausae sunt ne quis urbem relinqueret

The gates were shut so that no one might leave the city

tantus fuit omnium metus ut nemo urbem reliquerit

The fear of all men was so great that no one (actually) left the city

A result clause is also used with the following idioms:

• The impersonal phrase tantum abest ut + subjunctive

tantum abest ut nostra miremur, ut nobis non satisfaciat ipse Demosthenes

So far am I from admiring my own productions that Demosthenes himself does not

satisfy me

• with certain VERBS OF HAPPENING AND ACHIEVING: accidit ut, perficio ut,

facio ut

• in GENERIC RELATIVE CLAUSES, which characterise or make a

generalisation:

nemo tam stultus erat qui illud crederet - noone was so stupid as to believe that

quis est tam audax qui neget? - who is so bold as to refuse?

• after is sum qui:

ea est Romana gens quae victa quiescere nesciat

Such is the Roman race that it does not know how to be at peace when conquered

• after sunt qui, erant qui (there are/were those who...):

sunt quae nautas non ament - there are women who do not love sailors

41

• after numerical expressions such as multi sunt qui, pauci sunt qui, solus sum qui

• after the adjectives dignus (worthy), indignus (unworthy), idoneus (suitable)

After a negative main clause, if the relative clause is itself negative, qui...non... is

replaced by quin:

nemo fere tam sapiens est quin aliquando erre

Hardly anyone is so wise as not to make the occasional mistaket

Facienda

dux ita clamavit ut omnes milites eum timuerint

tanta erat fama exercitus Romanorum ut omnes gentes statim cederent

cena talis est ut eam edere non possimus

tot homines ad iudicium convenerunt ut iudex non audiretur

iste servus tam ignavus est ut numquam laboret nec umquam mihi pareat

ea est cui dii faveant

Nerone regnante, nemo tam stultus erat quin imperatorem laudaret

tanta est Christianorum constantia ut nolint deos nostros precari

erant qui negarent se coniurationi ulli interfuisse

adeo aegrotabat ut medicum arcessiverim

42

Language: Week 16

Indirect Questions

An Indirect Question is a noun clause dependent upon a verb of asking, enquiring,

knowing, telling etc., introduced by an interrogative word and with its verb in the

subjunctive. The interrogative forms are exactly the same as those used for direct

questions, except that num means 'whether'.

The tense of subjunctive used in an indirect question depends upon sequence of tenses

(primary or historic tense of main verb), but broadly corresponds to the tense used

in English. The following table should make things clearer:

question refers to

present

question refers to

past

question refers to

future

Direct

Question

What are you doing?

quid facis?

What did you do?

quid fecisti?

What will you do?

quid facies?

Indirect

Question

Primary

Sequence

He asks what I am

doing

rogat quid faciam

(present subjunctive)

He asks what I did

He asks what I will do

rogat quid fecerim

rogat quid facturus

(perfect subjunctive) sim

(future subjunctive)

Indirect

Question

Historic

Sequence

He asked what I was

doing

rogavit quid facerem

(imperfect

subjunctive)

He asked what I had

done

rogavit quid

fecissem

(pluperfect

subjunctive)

He asked what I

would do

rogavit quid facturus

essem

(future perfect

subjunctive)

A wide range of expressions may introduce a reported question (real or implied), so

be wary!

'Any' in a question (direct or indirect) is expressed by num quis or num quid which

must not be separated if used:

num quis adest? - is there anybody there?

rogaverunt num quid amississem - they asked whether I had lost anything

Facienda

eum rogavi quis esset; quo iret; quando perventurus esset

rogaverunt num quid audivissem

nemo pro certo habet cur Catilina haec fecerit

43

mox vides quanta multitudo ad hoc iudicium convenerit

Epaminondas mirabatur num clipeus fracturus esset

nescio utrum sapiens an stultus sit

dominum iratum docuimus quo coqui nocte fugissent

senex obliviscitur quot annos in eodem vico habitet

incertum erat uter consul victoriam maiorem reportavisset

servi nesciunt num dominus se liberaturus sit

Plinio placuit ut Traianum rogaret num ipse cuperet ut Christiani punirentur

Caesar dixit se cognoscere velle qualis et quanta esset insula

44

Language: Week 17

Causal Clauses

These are clauses which in Latin give a reason or explanation for the verb in the main

sentence.

• In Latin, the conjunctions quod, quia (because), quoniam, quando (since) introduce

an adverbial clause whose verb is INDICATIVE when the speaker or writer

vouches for the reason - that is, when the reason given for the verb in the main

sentence is presented as plain fact:

hostes, quoniam iam nox erat, domum discesserunt

- The enemy went home because it was now night

adsunt propterea quod officium sequuntur

- They are present because they are doing their duty

Note that, as in the above example, a demonstrative particle in the main clause (e.g.

propterea, eo, idcirco, ideo, hanc ob causam) may point to the causal clause.

• Quod, quia, quando and quoniam introduce a causal clause whose verb is

SUBJUNCTIVE either when the clause forms part of indirect speech or of

virtual indirect speech.

Virtual indirect speech is when the writer or speaker does not himself vouch for the

reason given, but reports the alleged reason given by somebody else, usually the

protagonist(s):

discesserunt quoniam fessi essent

- they departed because (they said) they were tired

{implication: they may or may not actually have been tired}

mihi irascitur, quod eum neglexerim

- he is angry with me because (he says) I have neglected him

This sort of subjunctive clause is very common after words of accusing, praising,

complaining, blaming etc. in the main clause (because the reasons for such emotions

are naturally subjective). Compare these two sentences which can both be translated

as “The king was hated by his subjects because he had broken the laws”:

rex civibus odio erat, quod leges violavisset - (alleged reason, subjunctive)

rex civibus odio erat, quod leges violaverat - (indicative verb, reporting a fact)

• If a reason is mentioned only to be rejected, the causal clause is introduced by non

quod or non quo and contains a verb in the SUBJUNCTIVE mood.

Sometimes the true reason follows in a clause introduced by sed quod or sed quia and

containing a verb in the indicative:

45

haec feci, non quo tui me taedeat, sed quod abire cupio

- I did this, not because I am fed up with you but because I want to leave

• A relative clause may have a causal meaning. Causal relative clauses always

contain a SUBJUNCTIVE verb and are frequently preceded by quippe:

hostes, qui adventum Caesaris ignorarent, flumen transierunt

- The enemy, since they were unaware of Caesar's arrival, crossed the river

consul, quippe qui praemonitus esset, haec exspectabat

- The consul expected these events, because he had been forewarned

• Quod is also used (with an indicative verb) in some expressions where English has

not 'because' but phrases like 'that, the fact that'. Some of these verbs and expressions

are listed here:

gaudeo quod - I am glad / rejoice that...

doleo quod - I am sorry that...

aegre fero quod - I am annoyed that...

omitto quod - I leave out the fact that

praetereo quod - I pass over the fact that...

addo quod - I add the fact that...

magnum est quod - it is no small thing that...

(huc) accedit quod - there is the further fact that...

Facienda

tacent idcirco quia periculum timent

ex acie effugi non quod mortem timeam, sed quod pila mea fracta erant

noctu in foro ambulabat Themistocles, quod dormire non posset

custodes confecti erant, qui per noctem vigilavissent

omitto quod reus uxorem meam tresque filias parvas trucidavit

46

Language: Week 18

Concessive Clauses

Concessive clauses are introduced in English by although, even if etc. and concede

either a fact or a possibility in spite of which the statement made in the main sentence

is true. In Latin, the conjunctions etsi, tametsi, etiamsi (even if) and quamquam,

quamvis, licet (although) may introduce a concessive clause.

• If the concession is admitted as a fact, Latin uses quamquam, etsi or tametsi with an

INDICATIVE verb, (or cum + subjunctive).

tamen is frequently found in the main clause to mark the contrast:

etiamsi tacent, satis dicunt (Cicero)

- Even if they are silent, they say enough

Romani quamquam itinere et aestu fessi erant, tamen obviam hostibus procedunt

- Though the Romans were tired from the march and heat, yet they advanced to meet

the enemy.

• If the concession is admitted as a possibility (which may or may not happen), the

Latin conjunctions etsi, etiamsi and tametsi are used with the SUBJUNCTIVE mood.

etiamsi non adiuves, haec facere possim

Even if you were not to help, I should be able to do this.

vera loqui, etsi meum ingenium non moneret, necessitas cogit

Even if my character were not bidding me (and it is), necessity forces me to tell the

truth

• The concessive 'however' followed by an adjective or adverb (e.g. “However fast I

run…”) is translated by quamvis followed by the SUBJUNCTIVE:

quamvis strenue labores, non ad tempus opus conficies

However hard you work, you will not finish the task in time

• A relative clause with concessive meaning will contain a SUBJUNCTIVE:

Caesar, qui illud suspicaretur, tamen obsides dimisit

Although Caesar suspected that, he released the hostages

47

Facienda

pecuniosus homo, quamvis sit nocens, damnari non potest

quamquam libros praeclarorum philosophorum legisti, non es sapiens quod eos non

intellegas

quamvis pulchra sit, Matildam in matrimonium non ducam, quod peregrina est

etsi medicum statim arcessivissemus, frustra venisset

etiamsi solus supersim, tamen in acie perdurem

48

Language: Week 19

Temporal Clauses, Phrases and Verbs of Fearing

Temporal Clauses are adverbial clauses which define the time when the action of the

main verb occurs in relation to another action. They are introduced by conjunctions

which in themselves define the temporal relation between the two parts of the

sentence.

Conjunctions introducing a temporal clause prior to the action of the main verb:

postquam - after that, after

ubi - when

cum - when

ut - as

simulac - as soon as

quotiens - every time that

ut primum - as soon as / the first moment that

cum primum - as soon as / the first moment that

Conjunctions introducing clauses contemporaneous with the main action:

dum - while, until quamdiu - as long as

donec - while, until cum - when

quoad - up to the time that

Conjunctions introducing clauses subsequent to the main action:

antequam - before that, before

priusquam - before

Ut, postquam, simulac, cum primum, ut primum, ubi, quotiens

• GENERALLY USED WITH AN INDICATIVE VERB IN THE TEMPORAL

CLAUSE.

• Latin uses the Future / Future Perfect and Perfect tenses in the temporal clause

where idiomatic (and less precise) English prefers the Present and Pluperfect tenses

respectively.

olea ubi matura erit quam primum cogi oportet (Cato)

- When the olive is ripe, it must be gathered as soon as possible

quae simulac audierit, abibit –

- As soon as he hears this, he will go away

eo postquam Caesar pervenit, obsides, arma poposcit (Caesar)

- After Caesar had arrived there, he demanded hostages and weapons

49

• Latin uses the Pluperfect tense after ubi, ut, simulac and quotiens to stress the

repeated occurance of the act in the temporal clause.

hostes, ubi aliquos egredientes conspexerant, adoriebantur

- Whenever the enemy saw anybody disembarking, they attacked them.

Facienda I

simulac cladem audivit, Lentulus Caesari copias auxilio adduxit

cum primum Cicero leges illas rogaverit, omnibus populis odio erit

Antequam, priusquam

• These are compound conjunctions, whose constituent words need not come together,

although quam must stand at the head of the time clause.

• The indicative is used when antequam and priusquam introduce a clause indicating

a relation purely of time.

priusquam respondeo, de amicitia pauca dicam (Cicero)

- Before I answer, I will say a few things about friendship.

• BUT when the idea of an end in view, a motive, or a result prevented is present in

addition to the concept of time, the subjunctive is used, in either the Present or

Imperfect tense according to sequence:

castra prius capere conati sunt quam nox adveniret - They tried to capture the camp

before night fell. (i.e. 'before night could fall')

Facienda II

celeriter effugit priusquam magister se videret

non prius abiit quam pecuniam accepit

gladiatores impetum fecerunt priusquam e pavore animos reciperemus

antequam sententiam dicistis, patres conscripti, volo captivos rogare num

quid habeant quod pro salute sua dicent

50

Cum

• When the clause introduced by cum refers to a present or future action, it contains a

verb in the INDICATIVE.

Latin requires greater temporal precision than English, and for example often uses the

future perfect indicative where English has an ordinary future tense.

poenam lues, cum venerit solvendi dies - You will pay the penalty when the day of

payment comes

• But when the clause introduced by cum refers to an action in the past, the verb is

generally SUBJUNCTIVE.

The Imperfect and Pluperfect tenses are used depending upon whether the action of

the temporal clause happens at the same time as or before that of the main verb.

Imperfect Subjunctive: Simultaneous Actions

cum haec diceret, milites eum occiderunt

- When (= while) he was saying these things, the soldiers struck him down

Pluperfect Subjunctive: Consecutive actions

cum haec dixisset, milites eum occiderunt

- When (= after) he had said these things, the soldiers struck him down

• A cum clause in which the idea of CAUSE or CONCESSION predominates over

that of time always has a SUBJUNCTIVE verb, whatever the sequence:

cum liber esse possit, servire mavult

- Although he might be free, he prefers to be a slave.

quae cum ita sint, Romam ibo

- Since these are the circumstances, I will go to Rome.

quae cum ita essent....

- Since this was so... / these were the circumstances...

• Cum can, when referring to a past action, be used with the INDICATIVE in the

following cases:

i) When cum has a frequentative / indefinite meaning: 'whenever'.

cum me vocaverit, ibo - Whenever she calls me, I will go

cum me vocavit, eo - Whenever she calls me, I go

cum me vocaverat, ibam - Whenever she called me, I wente.g. cum rosam viderat, tum

51

ver esse arbitrabatur (Cicero)

- Whenever he saw a rose, he thought it was springtime

ii) If the cum clause, though grammatically subordinate, contains the chief idea of the

sentence, whereas the main clause marks the time of the event - the inverted cum

clause.

The verb in the cum clause will usually be in the Perfect or Historic Present tense; the

main verb is usually Imperfect or Pluperfect.

hostes subibant muros, cum repente eruperunt Romani

- The enemy were nearing the walls, when suddenly the Romans rushed out.

SUMMARY : CUM

(tenses and moods of the verb used in the cum clause)

CUM = WHEN: indicative in primary sequence; subjunctive in historic sequence

CUM = SINCE, ALTHOUGH, WHEREAS: subjunctive always

CUM = WHENEVER: indicative

(tense of indicative = future perfect, perfect or pluperfect)

CUM = WHEN (in inverted time clause): indicative

Facienda III

cum Athenas pervenero in Parthenone deos precabor

cum proditor signum dedisset, Graeci statim arcem oppugnaverunt

quae cum ita essent, numquam postea ausus sum ei credere

cum cecini aliquis in me lapides iacit

cum dux contionem apud milites habuerat nemo fere applaudebat

cum nuntiatum esset Nervios hiberna oppugnavisse, Caesar magnis itineribus in fines

eorum progressus est

captivi iam paene effugerunt cum a custodibus in turri sensi sunt

cum epistulam legerem custodes armati ianuam fregerunt

Verbs of Fearing

The most common verbs of fearing in Latin are:

52

timeo, timere, timui

metuo, metuere, metui

vereor, vereri, veritus sum

The simplest way to express an idea of “fearing to do something” in Latin is to use the

verb timeo + PRESENT INFINITIVE

timeo illam arcem intrare

- I am afraid to enter that castle

timebant mori - They were afraid to die

This construction is not very versatile; you can’t express ideas such as “He was afraid

that somebody else would do something”.

More frequently, therefore, you will find that a verb of fearing will introduce a clause

containing a SUBJUNCTIVE VERB. These clauses will look very similar to Indirect

Commands or Purpose Clauses.

Reflexive pronouns such as se and suus will refer back to the subject of the main verb.

• If the clause is introduced by NE + SUBJUNCTIVE, then it means that somebody is

afraid that something will happen:

puer timet ne magister se puniat (present subjunctive)

- The boy is afraid that the teacher will punish him

puer veritur ne servi effugerint (perfect subjunctive)

- The boy is afraid that the slaves have run away

puer metuebat ne hostes urbem oppugnarent (imperfect subjunctive)

- The boy was afraid that the enemy would storm the city

puer verebatur ne fures gemmas suas abstulissent (pluperfect subj.)

- The boy was afraid that the thieves had stolen his jewels

• If the clause is introduced by UT + SUBJUNCTIVE, then the sentence means that

somebody is afraid that something will not happen:

mercatores timent ut sibi pecuniam dem (present subjunctive)

- The merchants are afraid that I will not give them money

mercatores timent ut Romani ab Hannibale vicerint (perfect subj.)

- The merchants are afraid that the Romans have been defeated by Hannibal

mercatores veriti sunt ut feminae advenirent

- The merchants feared that the women would not come

53

mercatores timebant ut senex periisset (pluperfect subjunctive)

- The merchants were afraid that the old man had not died

• The perfect participle veritus ne means fearing that…

veriti ne umbram videremus, in silvam intrare nolebamus

- Fearing that we would see a ghost, we refused to enter the wood

Facienda

metuo ne satis diligenter laboraverim

milites timebant ne signa sua capta essent

nos omnes verebamur ne barbari pontem captum delevissent

senex timet ut medicus se sanet

vereor ut vera dixeris