SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 1 A Detailed Overview of Special

advertisement

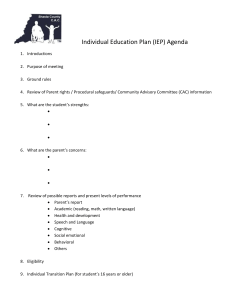

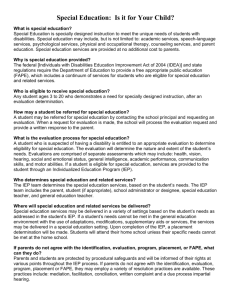

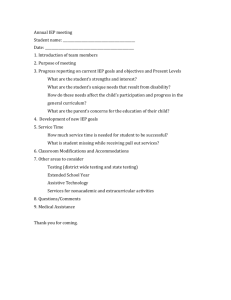

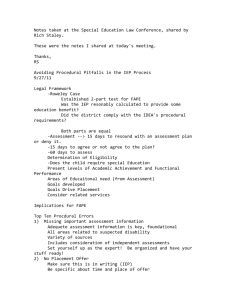

Running head: SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW A Detailed Overview of Special Education Law Deidre Henderson Ball State University 1 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 2 Abstract Special education law is a broad topic encompassing topics from a variety of federal mandates. The most common being the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA ’97, is the blueprint for granting all children with needs FAPE, a free and appropriate education. Eligibility must be determined prior to placement, but afterward, a IEP must be developed and the least restricted environment must be chosen. In the text, a discussion is held about the implications of related services that may be required in some IEP’s and the confidentiality of student information. Discipline was included to give insight on how students with disabilities should be treated equal, however stipulations to suspension and expulsions in order to ensure FAPE at all times. Keywords: IDEA, FAPE, LRE, IEP, Eligibility, Related Services, Confidentiality, Discipline SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 3 A Detailed Overview of Special Education Law Introduction The U.S. government first took interest in the rights of special education students in the twentieth century. During this period lawmakers were pressured to treat all citizens as equals in the country, beginning with the Civil Rights Movement. African Americans were the key members in demanding that every individual with unchangeable characteristics receive complete protection by the Fourteenth Amendment. It states: “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law, which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”, (United States Constitution). Coverage in the work place was important but primarily, in the education system. One of the greatest highlights within this time period was the landmark decision of Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954). Eligibility To receive federally funded services for students with disabilities, he or she must be deemed eligible by a battery of evaluations and assessments. Prior to any referrals or evaluations, the child must exhibit difficulty in one or more academic subjects or behavior. Developmental delays that seem dramatically abnormal are acceptations to the requirement as well. Assessment for eligibility is a main component of the entire Special SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 4 Education Process. It equips the test interpreters with statistics of performance, furthermore a better idea of how to diagnose the student. IEP teams that need to provide the child with assistance can utilize the data presented to generate a uniquely designed manner of instruction, fostering skills that lead to success in spite of the disability. Child Find is a section of the IDEA in Part C, requiring each state to 1). Locate 2.) Identify and 3). Evaluate any individual who may benefit from special education services. The process is in place to eliminate the academic deficits one may experience from the lack of early intervention. Though guidelines differ by location, the objective is to provide developmental compensation for students who are not developing as quickly or come from at risk families. Testing should be parentally consensual, informative and calculate developmental deficits. “As a requirement, the IEP team shall "review existing evaluation data ... including information provided by the parents [...], current classroom-based assessments and observations, and teacher and related services providers observations; and identify what additional data, if any, are needed [to meet the full requirements of disability evaluation, service eligibility, and placement” (Quote). States have the right to label a child as developmentally delayed up until age nine, therefore assessments should be multidisciplinary instead of standardized, to eliminate the misdiagnosing young school children. Larry P. vs. The State of California Litigation plagues all aspects of the law, and eligibility is no exception. Consider the case of Larry P. vs. The State of California (1979). During this case, parents complained about an IQ test that was culturally biased toward minority students and SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 5 those with learning disabilities. During this time period, Educable Mental Retardation (EMR) was the classification of students with disabilities. Considered to be uneducable in general education classrooms with other children. How they scored on the IQ tested determined their academic setting, the higher the school, the better the setting was for learning. Larry P. was considered a child with EMR (African American Student). The curriculum for these classes included social and functional skills, and some academia. His parents argued against the school district in court that the test was biased toward African American students with EMR because there was a huge disproportionality between African American students in these classes than white children. This was the only means of determining his academic placement. Statistics for the 1968-69 school year illustrated that though African American Students made up only 9% of the California Public School population, 27% of the special education was made up of blacks. The normative sample for this IQ test was entirely white, consisting of no other race or ethnic groups. It wasn’t until 1984 that the court ordered for California schools ban all forms of this test and find a more diverse approach to evaluating African American students. Thereafter, the government established the mandate that tests administered to non-white students be valid with a normative sample appropriate for its test taker. In ordinance with the law, all evaluations had to be non-discriminatory, have an appropriate normative sample, and have more than one means of effectively determining eligibility for special education services. Effective Assessments Effective assessment are conducive to the evaluation process for the reason that it allows the IEP team to create plans that lessen the gap between the individual’s actual SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW success and their potential performance. Parent involvement is a factor in effectively evaluations, which complies with IDEA regulations. Natural environments have reliably been the better setting for children because it removes any levels of stress that could be distracting or of discomfort. Non-discriminatory evaluation is vital because it reduces any chance of bias testing and un-valid, as well as unreliable outcomes. Relating back to the case mentioned above, culture must be considered in the evaluation process and how student backgrounds may affect testing outcomes. Two types of assessment exist. The first type of measurement tool is a curriculum-referenced test. These compare a child to his or her past abilities, track progress, and are scored with a pass or fail. Also known as criterion referenced test, students how perform the tasks allow insight on what they know and how much has been mastered. Usually curriculum tests are administered to screen for any developmental differences than the individual’s peers. Concerned parents, caregivers, or educators usually notice behavior that contrasts from other students, and they request these screenings. Standardized or norm referenced tests are the other. They are widely used assessment procedure to collect information on students’ performance levels and confirm or deny the screening examinations. It marks where a student should be performing in reference to his or her peers. “For eligibility decisions to be based on instructional strategies and curricular content, empirical evidence is needed about a significant discrepancy between regular classroom procedures and those required for a child” (Quote). IDEA states that students are eligible for special education if they fall one or two deviations below standard means. Norm referenced tests can account for students’ level of compared to standard means by offering a sample floor or “normality” that is 6 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 7 culturally and economically diverse. Samples contain a wide variety of students of different locals, and incorporate scores from test takers with and without disabilities. Examples of norm-referenced tools include the Behavioral Assessment System for Children (BASC) and the Battelle Developmental Inventory. Teacher and Parent Collaboration Concurring with IDEA, eligibility begins with appropriate evaluation, multiple tools to assess, no single usage of one criterion, and factors that collect data on physical, behavioral, developmental, and cognitive domains. In relation to the child find process, these measures are positive for determining strategies to approach deficits and then special education programs if more intensive teaching methodologies are necessary. While IDEA requires for educators to work with parents, norm-referenced test in addition to criterion and curriculum-based tests are avenues that can be combined to produce the most accurate and valid results. Utilizing all of these federally acknowledged resources in collaboration with human resources and communication. In the home, if a child seems to be developing slower or different than others requesting a screening can prevent any special education needs by early intervention. Classroom teachers and assistance can also emphasizes collaboration among key participants, notably parents and classroom teachers, including mutual goal setting, shared ownership, and shared decision making. IEP Over the course of PL-94-142 or the IDEA ’97, one major pillar that has been called the “Heart of IDEA ’97” is the Individualized Educational Plan or IEP. In other words, it is the document that lists in extensive detail how to provide a free and appropriate public education (FAPE), along with delivery methods for ensuring academic SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW and social goals for students with disabilities. A team composed of parents/guardians, relevant community members, medical professionals, general and special educators and others collaborate to develop a roadmap of what the child’s success will entail, with the interests and contribution of the student as well. Individualized Educational Plans (IEP) are mandated for these students and are created on a case-by-case basis by a team of i.e. parents, teachers, and related service specialists for the student to achieve academic, behavioral, and social goals. Components to the IEP include: 1). The present level of performance 2). Annual goals 3). Reporting of student progress 4). Accommodations, Modification, &Support Services 5). Least Restrictive Environment 6). Participation in statewide and District Wide Assessments 7). Frequency & Duration of Services 8). Transition Services. (IDEA ’97) While this list is very precise, there have been significant issues with the IEP. Schools nationwide have a difficult time truly implementing the plan for students with disabilities. Failures include “a delay in implementation […] and omission of required portions of the IEP”. A second issue, one of great concern, is the participation of students in the creation process. “Don’ts of the IEP” reject setting goals that are not unique to the child and neglecting behavioral objectives. Attempting to reach those targets without engaging the student is possible but very difficult. To avoid litigation and 8 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW failures, IEPs need to be carried out to the best of all participants’ abilities and that includes the students. According to Mason, Field, and Sawilowsky (2004), an emphasis is placed on engaging the students in the process to increase motivation to achieve, and to ensure the IEP is working. Some question the relevance of having “children” at the IEP meeting, or how will it enhance the outcome or any decision agreed upon. A survey conducted on the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) website inquired the level of student participation, responders’ comments on why this was important, and ideas for improving non-active statistics. “Active student participation and self-determination are areas that teachers lack training in” (Mason et. al 2004). It was mentioned that students who are a key player in the process have a better idea of their disability and can more assertively ask for accommodations. Instead of going through a trial and error process all year, young people can contribute to the IEP meeting and be more aware of their modification options. They can also collaborate with the teacher to help with achievement. Teachers and students alike experience frustration when multiple approaches are made to increase test scores and academic performance, and nothing seems to work. Most survey respondents had tried informal instruction for motivating and being accountable for ones’ own education, but admitted, “More training would be useful”. (Mason, et al 2004). Instead of using untested approaches, possibly ineffective, and an unproductive way to spend time, the student should provide information about their personal academic goals. In addition, career ambitions may move the transition process forward, and give others an idea of which teaching methods are helpful and which are not. Until more scientific and reliable data are collected on how to encourage and stimulate self-advocacy, recommending their involvement is essential. The 9 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 10 anticipation for breakthrough research may be great; therefore, teachers must be proactive in getting to know the child and finding out his/her learning style, personal standards, and post-secondary educational goals. The only way to do this is to involve the IEP’s greatest component, the student. It wasn’t a coincidence that “Secondary school teachers had more participation than middle school and elementary education teachers”. (Mason, Field, Sawilowsky, 2004). This however is the solution until empirical based information is released on motivation for success nationwide. IEP teams should begin integrating the thoughts and feelings of students in lower grade levels who currently attend meetings. Teams will have less deliberating to do when trying to figure out how the child learns, when the most logical thing to do is ask the student. Behavioral objectives should include comments on what triggers disruptive behavior and then agreements on steps of improvement and consequences of deviations. Strengths deserve a detailed summary in the IEP as well; they can be used as foundational building blocks to lessen weaknesses. Litigation Concerning IEP’s If these highly influential factors had been followed in the early 1990’s, it would have prevented the case of Doe & Doe v. Withers (1993). In 1993, West Virginia general education teacher Michael Withers had a student with disabilities in his classroom known as Doe. The IEP of Doe asked for the teacher to read the tests aloud. Nine tests were administered, all without being given orally. Doe failed each test, which required his family to pay for a second term of the history course. Ironically, when the student was placed in a different class for the same course, and the IEP was implemented, grades rose drastically and he successfully completed the class. During the hearing, the court ruled in favor of the Doe’s parents. The school administrators and officials were dismissed from SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 11 penalization because they had given Withers specific instructions to obey the IEP, which were deliberately disobeyed. In the end, Withers had to reimburse the parents $5,000 in compensatory damages and $10,000 in punitive damages. The Effects of IEP’s Over Classroom Teaching Strategies Educating a child is a hefty task, especially if the teacher knows very little about them or their limitations. Much more research is vital to truly implementing IEPs and the overall process of it. Until then, students need to be incorporated in the conversation so that crucial information can be given to progress the academic, behavioral, and social skills of every child in every meeting. Not only will it allow for better ideas of how to approach learning barriers, but it will provide insight on effective teaching strategies. By following every parameter of the IEP process and all guidelines stated by the IDEA, teams are one step closer to process ensuring FAPE for every student. FAPE According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA ’97), the law requires that children and students with disabilities receive a free and appropriate education (FAPE). Federal regulations describe FAPE as any special instruction and related services which: “are provided without cost to the family” (IDEA) and funded by the public, meets the standards of the state education agency in charge, the appropriate academic institution within the state, and is administered in a way that conforms with the individualized education plan that meets IDEA section requirements. An essential components of FAPE is access to the least restrictive environment (LRE) for learning, whether that be incorporated in mainstream classrooms or self-contained. With an SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 12 extensive amount of legal stipulations in place, there still remains an issue with fully providing FAPE for each child with a disability. Environmental barriers hinder children with disabilities, which can violate FAPE, or lead to litigation that prolongs the appropriate placement for the child. Some that are less severe include physical limitations and perceptions of classmates of the student with disabilities. To alleviate these challenges teachers and other school educators can collaborate with parents and community members to determine classroom modifications. Awareness of the student’s disability is important for all adults who are responsible for his or her success. Within the classroom, peers can be encouraged to be accepting and supportive. Students in school can have a substantial impact on the self-esteem of individuals around them; therefore offering insight of disabilities that does not violate confidentiality codes can make a difference. Board vs. Rowley Court Case As previously mentioned, litigation can be the result if the rights of FAPE are breached. Consider the Board of Education of Hendricks Hudson Central School District v. Rowley (1982). In 1982, Amy Rowley was a ten-year old girl with special needs. Due to being hearing impaired, she required the assistance of a sign language interpreter. The school however did not feel she needed this service. Her parents disagreed. It was evident that Amy possessed lip reading skills, but could only comprehend sixty percent of spoken language. This is turn was the bases for the claim; their daughter needed a full time sign language interpreter. The school countered the argument, stating that lip reading and necessary accommodations did in fact prove she was receiving FAPE. During the trial, the High Court established “a basic floor of opportunity” idea. Mirroring this belief of the SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 13 Supreme Court, the High Court made aware that districts are not responsible for providing every child with the maximum level of services available to meet the IEP objectives. The IDEA upheld the verdict in writing by mentioning optimal level services are not mandated. Schools are only required to provide a basic level of opportunity with some educational benefits. Incorporation on FAPE Yielding the best educational practices to all students seems quite logical, but it is not a legal mandate. Federal education laws only oblige schools to find methodologies for student success to some degree. Basic needs are the primary goal when an IEP is formed and meeting these goals ensure FAPE. A specific component of the IEP, the LRE, is; however, one decision teams must heavily deliberate upon. Classrooms settings deemed appropriate must be the least restricting and allow students with disabilities to co-learn with their non-disabled peers to the greatest extent possible. LRE Granting FAPE obliges the establishment of a student’s LRE. The intent for this provision is to protect children with disabilities who should be educated alongside their non-disabled peers. Make note that a regular education classroom is not always the appropriate least restricted environment for every student and likewise students who do need special services may not always need to be removed from the general education setting. In fact, there is a continuum that identifies learning environments from the least amount of peer interaction to the greatest. Students, who are able to learn in regular classrooms where the teacher can meet all student needs, are placed in general education SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 14 classrooms. Others may need to attend resource rooms for a designated period of time everyday, but can perform well in class with their non-disabled peers. The most restrictive environments are for students who are unable or not allow to attend school, some cases include: hospitalized students, expelled students with disabilities, and those who are residential learners. Local middle school educators and teaches reported on a project based in their respective public New York schools. It offered reassurance that SWDs are capable of learning side-by-side peers that did not have learning disabilities. The first objective was to follow FAPE and all of the components that went with it. Thousands of students in special education do not need to be there and placing them in a more restrictive environment is more detrimental than helpful. The article written to document the project was entitled “Including Students with Disabilities Into the General Education Science Classroom”. Initially, it would seem farfetched to intermingle pupils of such significant learning differences in science, however this article provided substantial evidence and an ideal starting place for how to implement such rigorous demands in a science classroom. An LRE Case Study Data was collected at the beginning of the project (not an experiment), and the facts where dismal; “Two-thirds of students with LDs studied had at least one reciprocal friend […] were less frequently represented in the category of teacher attachment” (Cawley, Hayden, Cade, Baker-Kroczynski 2002). It went on to mention the belief concerning SWDs and their academic incompetence compared to regular classroom students; teachers were more likely to reject the students, peers were rude and uninviting SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 15 in social activities, etc. Lastly, major issue addressed was “preventing students’ behavior from interfering with their academic success” (Cawley et al 2002). Contrary to the notes collected in the beginning of the project, collaboration, innovation, and co-teaching truly set a new standard for students and LREs. The authors were sure to make aware that typical public schools’ have underdeveloped special education programs. Utilizing detailed criteria may aid preventing great quantities of SWDs from being placed in the wrong LRE. This following checklist has been of great importance and used nationwide. Unfortunately, its beginning was sparked by litigation. Sacramento vs. Rachel H. Court Case The case of Sacramento City Unified School District v. Rachel H. by Holland (1994) involved Rachel, an eleven-year-old girl who was placed in special education early on due to moderate mental retardation. Her parents requested that she be placed in a general education classroom, and the school offered only to place here there for nonacademic, but more socially oriented course. For the remained of the day, all educational classes were the best LRE option for her. At the hearing, to decide legislatively what the best placement was, the court “applied a four-pronged test now known as the Rachel H. four-factor test” (cite the book). In summary, the test listed four criteria: 1.) Is a more restrictive environment any more beneficial than a lesser restrictive environment with the addition of aids and services 2.) Will the social and non-academic needs of the child be met in a more restrictive environment or the least restrictive environment 3.) Will the presence of the child in the LRE disrupt, upset, or negatively affect the GE classroom teacher or students 4.) What are the financial costs of placing them in a mainstream SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 16 classroom? The final verdict found in favor of the parents. Aids and services were to be used for Rachel in the general classroom with students without disabilities. Ensuring Appropriate Placement Misconceptions of children with disabilities often limit or weaken the quality of learning in a general education classroom. Teachers need to be well informed of whom they are instructing and updated on the current studies and information on their condition. For FAPE to be in place, a uniquely designed education plan should be implemented to ensure academic success. This project definitely set the standards for a truly achieved mandate as such. Science courses may be the first class to try when integrating students with disabilities with their non-disabled peers. Teachers and educators though need to be diligent in working together, looking at each student as a capable individual, and requesting help from other professionals to utilize teaching techniques, in efforts to make all students successful. All disciplines of professionals should be considered in every case and used as needed, including the key roles of related service providers. Related Services For students who qualify, their IEP may include the usage of related services. Related services are strategies used to provide FAPE in the determined LRE for students with disabilities. Moreover, they are categorized as “developmental, corrective or supportive services” (Downing, 2004). Assistances such as the few described below do not conclude an exhaustive list; however, it illustrates that health oriented conditions must be present eligible to receive them. SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW Audiology Services are administered when the student has a hearing loss and or communication deficits. Audiologists screen students for hearing capabilities and refer those who may be at risk for verbal interaction issues to speech language pathologist (SLPs). SLPs then reassess, diagnose, and treat arising debilitations. Assistive technology is a second avenue used to increase performance in the classroom. Every student is considered regardless of special education placement for technology support. According to the IDEA “assistive technology is any item, piece of equipment, or product system, whether acquired commercially off the shelf, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain or improve the functional capabilities of a child with a disability” (IDEA Regulations, 34 C.E.R. Sec. 300.5). Well-known systems that have been openly accepted and used are screen readers, amplification systems, and math pads. Counseling is available for the child who qualifies and his or her parent in the form of legal guardian counseling and rehabilitation. The same service for primary care givers affords insight on the student’s disability, which is highly beneficial for many reasons. First, it allows an opportunity for families to make sense of what their child can do. Afterward they can be knowledgeable of what challenges lie ahead and why. Second, this information will propel the IEP process. Awareness of the disability by families, teachers, and related service providers makes distributing tasks to benefit the student easier. Advancing the IEP process with confused team members weaken the chances of creating a foundation of support and academic assistance to get back on track. Last in this list is therapy. Occupation, physical, and rehabilitative therapy all fall under this category of related services. Specialists for each of these spend limited to a substantial amount of time training a student to use their bodies in effective ways and increase 17 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 18 mobility. Section 504 under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 states that “schools are responsible for providing the health services that are necessary for students with disabilities to attend school […] and by a qualified school nurse or other qualified person”. No funds; however, are allotted to schools by the government to cover these costs. This is because IDEA and The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 are separate mandates. Whole Qualifies for Related Services Note that not all students with a medical diagnosis are automatically eligible for services, it is important to understand the stipulations for receiving them. The amendment requires that “Any person who (i) has a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more of such person’s major life activities, (ii) has a record of such an impairment, or (iii) is regarded as having such an impairment” (29 U.S.C. Sec. 706(7)(B)). In other words, the physical ailment must affect one or more body functions, the brain to the point of slowed learning ability, and or caring for one’s self because a sensory or motor dysfunction. The IEP team ultimately decides whether or not the condition limits one or more life activities. Learning is the prominent domain observed. An example of a qualified child may be one with articulation issues. If this prohibits the child from reading, comprehending, speaking, or understanding, a SLP is a wise related service to implement into the IEP. Cedar Rapids vs. Garret F. Court Case Though many student with physical disabilities have been assisted by related service providers, cases have risen where districts attempt to deny educating these children due to lack of trained personnel or funding. One can clearly visualize because of the Cedar Rapids Community School District vs. Garret F. (1998). In the case, a young SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 19 man had been in a near fatal motorcycle accident which left his spinal cord severed. For some time, his family attended his classes and provided him with physical assistance. His family assumed all financial responsibility, until Garret’s mother wrote to the district. She requested that the school district begin paying for his expenses and nursing services, but was denied. Filing a complaint to the Iowa Department of Education, an Administrative Law judge claimed that it indeed was the responsibility of the school district to take full financial responsibility for the nursing staff and training for Garret. In- Class Intervention as Necessary To prevent the denial of rights in any way that Garret’s family was, current day educators are responsible for explaining all possibilities for students to excel if health related aids are necessary. The IDEA requires that students receive related services, but only as needed. A variety of services exist, ranging from audiology assistance to technological devices that a student can operate on their own. Only students who exhibit physical or bodily limitations that adversely affect their ability to learn, function independently, and those able to care for themselves qualify. As teachers, parents, and other IEP team players, it is important to take into consideration the disability of the student yet understanding that there is a difference between accommodations, modification, and related services. Confusing these may limit the potential of students that would have otherwise achieved more with the proper medical assistance. As mentioned above, a related service is a corrective, developmental or supportive strategy and a requirement for ensuring FAPE. Accommodations, such as time extensions, simplified instructions, and extra help are all instances of accommodations modified test deliveries and tailored homework assignments, are changes in materials used to test. SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 20 Modifications on the other hand are used for more moderately disabled learners. Students who receive these are taught a less complex level of the material covered in class, is required to complete less homework, and have specific expectations of what is learned set by the IEP team. Simply put, modifications are changes in the curriculum while the others are not. Occasionally, students who are eligible for related services and special education in general have issues with behavior. Similar to other students, they have the same consequences; however, IDEA created a set of directives that govern the time allotted for he or she to be removed from school, and how to proceed with caution harsher discipline must be exercised. Discipline By definition, discipline is the practice of training an individual to obey rules or a code of behavior and enforcing consequences to correct disobedience. Subjecting all students to suspension or expulsion describes the application of discipline across the nation, in schools. Though each term includes a documented removal from school, suspensions usually range between one and ten days. Expulsions mandate that the student permanently leave the school for up to one year, though most likely, he or she is expelled for one semester. Recently, many public schools relied heavily on these punishments, as a first option for a wide variety of deviations. The practice has risen from the philosophy “zero-tolerance policy”; which means academic administrations will not tolerate violent acts or rule infractions of any sort. Such an implementation has caused uproar in special as well as general education. Both suspension and expulsion have been considered in significant cases “like alcohol and fighting […] to seemingly minor instances such as SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 21 possession of Midol and nail files” (Skiba 2009). In addition, researchers have found that students who are suspended view their punishment as just the opposite; it is a reinforcer to their misbehavior. Current Discipline Policies For special education students, there are two options, long term and short term, for discipline depending on how close they are to the ten-day rule. Whether the delinquent behavior is caused by or totally independent of the disability, the individual is susceptible to the consequences of their non-disabled peers. So long as the punishment does not exceed ten days, they are treated equal. Behaviors provoked by the disability can require a need for removal beyond ten days. At that point, an IEP meeting will be held with the parents, teachers, school administrators, and IEP members to determine the reason for the misconduct. The actual IEP plan needs to be amended and the appropriate placement revised. More specifically, a behavioral intervention plan (BIP) should be created and implemented. If there was an existing one, behavioral expectations are edited. Afterward, students return to their original placement unless “(1) parent and district agree to a different placement, (2) hearing officer orders new placement, or (3) removal is for “special circumstances”” (IDEA 04). Misconduct such as dangerousness or extreme social deviations (i.e. drug possession, weapon possession) are different cases. Once these have been determined as independent of the disability, the student is considered for Interim Alternative Education Setting (IAES). Post Ten-Day Rule Discipline Alternatives SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 22 Above, BIPs and IAES were mentioned. Both are alternatives to expulsion while upholding the law and providing the student FAPE. “Once a student with disabilities has been removed for more than ten school days, IDEA ’97 requires that the school district conduct a functional behavior assessment and implement a behavioral intervention plan” (Skeiba 2009). The student’s frequent wrongdoing must be evaluated by a series of observations, interviews, scientific-based tests, and checklists. Combining the data will generate a hypothesis establishing the root of the disruptive behavior. “A school may place a student with a disability in an IAES for up to forty-five days for possession of drugs or weapons” (IDEA 97); students without disabilities are given the same penalty because the action is not a manifestation of a disability. Administrators have the right to request this type of long-term removal if substantial evidence is provided. Exhibiting a considerable likelihood that the individual will harm himself or another person are essential pieces to having this request approved by the court system. Acts of dangerousness do not constitute a legitimate reason to remove the child without parental consent; districts may, however, petition a hearing officer to deny that student entry into the school for an extended period of time. Honing vs. Doe Court Case Litigation has become nearly automatic when disciplined has resulted in a violation of FAPE. Consider the case of Honing vs. Doe (1988). In a California school district, Superintendent of Public Instruction (Honing), expelled two emotionally disabled students (Doe et. al) for disruptive behavior and violence. All educational services were revoked and the parents exercised their right to Due Process, for FAPE was being violated. Furthermore, Honing infringed upon the Stay Put provision, which states “that a SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 23 child cannot be moved from his or her current educational placement during appeal” (IDEA 97). The prohibited placement change disobeyed the least restrictive environment (LRE) mandate of the IDEA as well. Consequently, this case “set the precedent that students with disabilities may not be unilaterally removed for disciplinary reasons beyond ten days without educational services or an alternative educational placement” (Hulett 2009). Students with disabilities who are expelled or removed for long periods of time are protected by IDEA, which does not condone a “cessation of services”. Regardless of the new placement setting, students must continue receiving services provide by the district. Positive Interventions Encouraging positive alternative to negative behavior should be the first resort for students with disabilities and general education students alike. Suspension and expulsion are increasingly being used for deviations that are minor compared to their harsh punishment. Applying in class strategies to combat undesirable actions will not only help students with disabilities but their peers, especially in inclusive classrooms. The Comprehensive Model of School Violence Prevention is an approach that is divided into three levels. The first recommends that educators create a school wide positive environment with connections between students and adults. Teaching programs that give insight on alternatives to violent outlashes. Skiba mentions: unambiguous behavioral standards, peer mediating, bully prevention, and assertive classroom management strategies. Next, schools should use scientific based methods to target students at-risk whom may use more forceful tactics during times of adversity. Anger management and mentoring are ideas that would greatly benefit each student’s life skills alongside the SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 24 growing safety of the others in the school. Lastly, in response to disruptive behavior, “options might include functional assessment, restorative justice, community based services, school based mental health services and crisis management strategies” (Skiba 2009). In the Classroom To avoid as much violence and misbehaving as possible, teachers and academic colleagues can incorporate the model mentioned above in every setting. Collaboration is a key factor in resolving issues provoked by anger, just as it is for alleviating wrongdoings manifested by the child’s disability. As educators, it is important to maintain a safe learning environment for all students, yet utilizing the appropriate disciplinary measures to correct behavior without violating educational rights. Furthermore, children with disabilities who consistently act out may have documents that fall into their student record. Confidential records by law demand that only certified adults know, view, and handle the information. Confidentiality The Family Educational Rights Privacy Act, commonly known as FERPA, was first passed in 1974. Such an act greatly and positively affected many students and families with special needs. Privacy of health and academic information had been legally deemed highly critical because “unless confidentiality is protected, students will not come forward with their problems and thus not receive the help they may need” (Howe, Marimontes 1992). This monumental document contains four parts that describe the ways to ensure confidentiality is maximized and funding policies as well. The first part explains how to comply with all FERPA sections to continue receiving funding. SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW Secondly, parents must grant consent to their child’s academic institution when administrators are making placement changes for the student. The following section expounds upon the federal funding and the denial of any monetary assistance to schools that do not restrict student records to unauthorized parties. Lastly, it states that agencies conducting any sort of national educational research follow strict guidelines for to protect all students whose information is used, and that no identifiable information is disclosed. In reference to the FERPA 74 Act, identifiable information is any piece of evidence “related to a student and maintained by the institution or by a party acting for the institution are considered education records” (FERPA 74). One can also explain this information to any parent or IEP member as “any personally identifiable information about a student’s past or present health and developmental status” (IDEA 1997). All information categorized as confidential whether it be personal information like name and address, or health diagnosis is done so because it is not appropriate to share with the public. It is private because it may carry the potential of causing harm to the family if misused by an unauthorized individual. Newport-Mesa Unified v. State of Cal. Dept. Of Ed. Another case that laid current day precedents was the trial of Newport-Mesa Unified V. State of California Department of Education. Rather than improper testing assessments, California school districts found themselves in fault of violating an educationally based law and a federal law. The question was whether or not schools had permission to give parents a copy of the test protocols used to evaluate their children, as the IDEA states and violate the copyright laws, and contrarily vice versa. 25 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 26 Mr. Anthony Jackson had seven-year-old son that required special education services. Prior to the testing, he requesting a copy of all measurements used to evaluate his child at the IEP meeting. His request was denied. Mr. Jackson invoked due process and filed a complaint stating it was a right for him to have these materials for “fair use” within five days of his inquiry. The counter claim issued mentioned that it was against copyright laws to distribute the test protocol to anyone under any circumstances. After the test creators were summoned to court and extensive mediation, FERPA subsequently added: “Accordingly, if an educational agency or institution or participating agency maintains a copy of a student's test answer sheet, then it must provide the parent with an explanation and interpretation of the record, which could involve showing the parent the test question booklet, reading the questions to the parent, or providing an interpretation for the responses in some other manner adequate to inform the parent." The priority in this case was to underscore the importance of both copyright laws and the rights of parents with children in special education. Mediation settled the case, thus compromising between the two parties. Authorized Personnel & Consent As far as the IEP meeting goes, where all of these individuals will meet at once, “discussions can be held about the student’s functional abilities regarding educational and service needs […] but if the IEP meeting focuses on medical or clinical diagnoses, one can run the risk of violating FERPA (cite). Educators and administrators must be sure to include all parents and care givers that consent must be given to all outside parties that wish to access the student’s health records. Members not associated with the IEP team or SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 27 authorized school personnel may be: parents of the student, who do not have primary custody, agencies conducting research, or any person of legitimate educational interest. While the concept of legitimately interested individuals may seem simple, the crucially of being sure is one of great importance. A person has legal access to review the record only if it will satisfy their professional responsibility. These school personnel can range from principals to teachers aids, as long as the information they request will beneficial and educationally related services to the student for contract fulfillment objectives. Parents have the right to request student records that, by law, needs to be accessed within fortyfive days. Prior to the refilling of any document requested, parents and students over eighteen have the right to challenge data collected that may be viewed as inaccurate. In regards to releasing information to agencies and organizations, written parental consent must be given to release information about the student in special education under the age of eighteen. One amendment of FERPA states that schools have the freedom to disclose any identifiable information inquired by: a court order, documents containing abuse, federal agencies that are auditing or evaluating financially supported programs, emergencies that will directly affect other students’ safety, income tax documents, institutions looking to enroll the student, and any agency doing educational studies that agree to adhere to confidentiality standards and agree to destroy all student information immediately. Brief Overview Overall, confidentiality is a concept that developed from ethical principles. It is a foundation for building, facilitating, and maintaining healthy relationships in special education. To remain in good standing with the law, professional responsibilities and SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 28 families, educators and others who work with students in academic settings must be cognizant and empathetic to the privacy of those they serve. Conclusion Overall, the course influenced my decision to incorporate everyone in the community and taught me to collaborate with all IEP team members. Individuals who have an interest in the child will be given a role to support and further the success potential; along with carrying out the requirements of the IDEA. My responsibility is to guarantee the child’s FAPE, a free and appropriate education. Embracing all of the student’s significant community members, IEP team members, parents, and families alike, a very uniquely designed instruction will be generated, implemented, and enforced. SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 29 References Cawley, J. Hayden, S. Baker-Kroczynski, S. 2002 Year. “Including Students With Disabilities Into the General Education Science Classroom.” Exceptional Children Vol. 68, (No. 4): pp. 423-435 Daniel R.R. v. State Board of Education, 874 F.3d 1396 (9th Cir. 1994) Doe & Doe v. Withers. (1993). IDELR 422 Downing, J. (2004). Related Services for Students with Disabilities: Introduction to the Special Issue. Intervention In School & Clinic, 39(4), 195-208. FERPA (1975) Honing vs. Doe, 479 U.S. 1084 (1998) Howe, K., Miramontes, B. O. (1992). The Ethics of Special Education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press Hulett K. E. (2009). Legal Aspects of Special Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (Education for All Handicapped Children Act 1975), Pub. L. No. 94-142, 89, Stat. 773 Larry P. v. Riles, 793 F.2d 969 (9th Cir. 1984) Mason, C., Field, S., Sawilowsky, S. (2004). Implementation of Self-Determination Activities and Student Participation in IEPs. Exceptional Children, 70, 441-451. Newport-Mesa Unified v. State of Cal. Dept. Of Ed. 371 F.Supp.2d 1170 (2005) SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW Reppeto, B. J., Gibson, W. R., Lubbers, H. J., Gritz, S., Reiss, J. (2008). Practical Applications of Confidentiality Rules to Health Care Transition Instruction, Remedial and Special Education, vol. 29 (Number 2) Pgs. 118-126 Sacramento City Unified School District v. Rachel H. by Holland, 14 F. 3d 1398 (9th Cir. 1994) Sealander, A. K. (1999) FERPA: Basic Guidelines for Faculty and Staff A Simple Step by Step Approach for Compliance. Professional School in Counseling, Vol. 3 (Number 2), Pg. 122 Skiba J. R., Special Education and School Discipline: A Precarious Balance Behavioral Disorders, Vol. X (Number Y) Pg. Z 30 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW 31 Personal Philosophy Special education law has been quite an insightful course that has taught me the discrepancies of some legal protocols and how to fulfill the requirements of others. IDEA and Article Seven have become important documents that identify and clarify any question I may have about students’ rights and those of their families. The most importantly concept in my opinion was how to ensure that every student in special education receives FAPE. My knowledge about related service specialists has modified my perception about how each person of interest could benefit the student. Incorporating learning strategies from multiple developmental domains into everyday activities is a strategy that I admire and use often. According to the IDEA, IEP teams are to do the same. Working together to guarantee the least restrictive includes classroom accommodations, collaboration between general educators and special educators, along with families. Furthermore, it is my objective to integrate teaching strategies into everyday activities for my special education students. For example, if a student has a reading disability, I would urge for all IEP team members to ask the student to read different words in different environments including stop signs, menus, and age appropriate advertisements. Not only will this show the student he or she is supported, but that individuals reading skills will increase in more SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW than just academic settings. Within the classroom, dialogic reading is a strategy I learned about to minimize any limitations they may have. In regards to LRE, my main source of guidance will come from the Rachel H. Assessment that asks: 1. Is a more restrictive environment any more beneficial than a lesser restrictive environment with the addition of aids and services 2. Will the social and non-academic needs of the child be met in a more restrictive environment or the least restrictive environment 3. Will the presence of the child in the LRE disrupt, upset, or negatively affect the GE classroom teacher or students 4. What are the financial costs of placing them in a mainstream classroom? If a student in a general education classroom and that specific LRE is being disputed, my goal will be to co-teach or exhaust all push in services first. Later, the general education teacher and I will evaluate the success of these methods and once that is unsuccessful, a change of placement will be made. Maintaining similar academic expectations and behavior across all macro systems will increase the opportunity for success. The student will learn to be respectful and behave in a way that can be observed. Therefore if a deviation occurs, the student’s usual behavior can be analyzed in comparison to the situation that triggered unacceptable behavior. 32 SPECIAL EDUCATION LAW When addressing eligibility and assessment, I found that using a transdisciplinary methods is the ideal way to collect valid data and determine placement from there. All children learn and develop at different paces; however, there are some similarities. Normative samples help identify those congruencies while providing information by students of diverse backgrounds and SES’s. Litigation is bound to occur, resembling [insert Spanish girl and wrong test court case]. As a special education teacher, I would strongly recommend a list of assessments be administered (i.e. doctor’s records, interviews, observations, screening and diagnostic assessments). 33