Expenditure Data Needed for the ICP

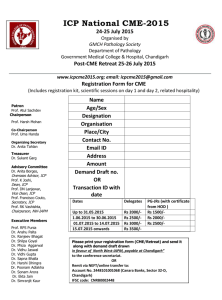

advertisement