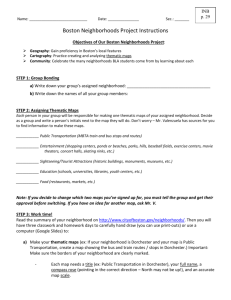

Planning for Social Diversity

advertisement

PLANNING FOR SOCIAL DIVERSITY Emily Talen University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign Champaign, Illinois Planners often define urban planning as being about change: encouraging change that is desired and discouraging change that is not. In the case of planning for social diversity, however, it might be more apt to define urban planning as being about stability: how to keep a place diverse and prevent it from being overrun by one particular social group or one particular land use. In such cases, the goal of urban planning may be to encourage change that supports a stable heterogeneity – the continued presence of social diversity – while discouraging change that undermines it.1 That social diversity in urban neighborhoods is something to be valued and encouraged has a long history in urban planning. By mid-20th century, the rejection of suburbia by intellectuals and planners was based on a perception that it lacked diversity and therefore was “anathema to intellectual and cultural advance”. From Jane Jacobs to Richard Florida to sustainability writers, our best places are thought to be those where the spatial isolation of groups defined by income and race are nonexistent.2 Alongside these claims, there are now a wealth of ideas about how urban planning and design should be used to support social diversity: the need to mix housing type, support locally-owned business, provide public spaces that connect people and provide neighborhood identity, promote street connectivity, maintain short blocks, maximize exchange through the public realm, etc. Despite this knowledge, the reality is that planners are most often confronted with indications of decreasing diversity: increased income segregation, widespread automobile dependence brought on by land use segregation, cycles of disinvestment and increasing concentrations of poverty, and increasing distances between where people live, work and shop. My interest is in exploring the approaches, tasks, or strategies in urban planning that can be leveraged in the support of social diversity. In essence: is urban planning doing all it can to support and stabilize neighborhood-level social diversity? Looking beyond 1 Neighborhood social diversity is defined here as the mixing of people of different income levels, ages, races, ethnicities, and household types in one relatively small area, perhaps 160 acres (1/2 mile square). 2 Talen, 2005; Mumford, 1938; Sarkissian, 1976; Jacobs, 1961; Florida, 2002; Beatley and Manning, 1997. 1 physical design proposals like the need for mixed use. mixed housing type, and connectivity, there is a need to structure the planning process itself in ways that support diversity. Can diversity be stabilized from a generative process? To what degree can diversity be supported by, or even generated from, an emergent planning approach? To some degree this question rests on whether generative processes are dependent upon the underlying social characteristics of neighborhoods. Undoubtedly, the ability to successfully evolve urban form is not indifferent to the underlying population. What may be particularly important is not whether a neighborhood belongs to one social class or another, but whether a neighborhood is socially complex – heterogeneous vs. homogeneous. Under American rules of land development, social diversity is unlikely to be generated through emergent processes by themselves. In addition, neighborhoods with exactly the kind of morphology that would seem to best support diversity (good connectivity, mix of uses, mix of housing type) are increasingly scarce, highly desired, and gentrified. Often the complexity that exists in social terms is in the process of breaking down. One wonders whether collaborative social processes and self-organization can easily exist in socially complex contexts. The evolution of complex geometries may thrive in societies where there are strong cultural and religious dictates that provide an underlying framework, but what of societies of widely competing interests, values, cultures, ethnicities and preferences? Engagement may in fact be motivated by a desire for grouppreservation – protecting one group from another in ways that are not mutually reinforcing. Certain urban morphologies are important for sustaining diversity, but generating and sustaining those morphologies in socially diverse places may require a specifically tailored planning approach. The question is, how do we get a neighborhood to collectively want to sustain the elements that support its diversity? Will a diverse group of people want these sustaining forms and patterns? In a society with such strong segregationist spirit, where social mobility is equated with spatial mobility, something more specific than freeing people to engage in bottom-up, self-generative processes may be required. Engagement, self-determination, social networking – all of these are important for the support of diversity, but more is required. Proposal: Neighborhood planning for social diversity While “end-state” planning is often considered problematic, engagement in a planning process to produce a plan may in fact be what socially diverse neighborhoods need. The production of a neighborhood plan does not need to be conceived as an end-state project, but instead as a way of having a focused discussion. Generative processes – specifically, 2 shared management of the neighborhood – can be positioned within the context of neighborhood planning implementation. The act of producing a neighborhood plan may be one of the most important tools we have in the quest to preserve diversity – agreement on how competing factions are supposed to get along. In the case of the socially diverse neighborhood, the “image” of a shared future might be essential. The focus should be on facilitating a process of collaboration where the diverse nature of the neighborhood is borne in mind. Someone has to make sure that the emerging “collective intelligence” of recurring responses to recurring problems is not about coopting space for control by one group or another. People need to think positively about the process and each other to ensure that a collaborative process reaches for something collective. I think the place to start is with the process of neighborhood planning. Shared management of a place emerges from that process, as one component of a neighborhood plan. The implementation of design that supports diversity requires a four step process that is different from conventional neighborhood planning in that 1) there is a pre-planning effort to educate neighborhood residents about the diversity that exists; and 2) a citizen action group is formed ahead of time that is not only representative of the diversity that exists, but challenged by planners to consider the stability of diversity as an essential focus for neighborhood planning. Diversity-based planning is essentially a modified version of what is now generally accepted as community visioning or planning by charrette. There are four main steps. Step One – Target diverse neighborhoods. Planners make an assessment of neighborhood diversity in their metropolitan region; they identify neighborhoods with high levels of social diversity. Neighborhoods should be the planning framework for diversity. Planners, directed by municipal leadership, make the decision that diverse neighborhoods are to be targeted for special planning effort and focus. They decide to initiate a neighborhood planning process for targeted diverse neighborhoods. The selection will be based on existing diversity, threats to diversity and potential for instability, and the likelihood of success (citizen interest, active and engaged local leadership). Planners then approach local leaders in the targeted diverse neighborhood. They create a citizen action group composed of local leaders that represent the diversity of the neighborhood. This group is then charged with coordination and facilitation of the neighborhood planning effort. Step Two – Build public awareness. With input from the citizen action group, planners work to develop public awareness of neighborhood diversity, focusing on its positive aspects and the need to support it. Working with the citizen action group, they implement strategies that increase recognition and awareness of neighborhood diversity. Planners should encourage all means of exploration and celebration of the social complexity of diverse neighborhoods. 3 A. Show the neighborhood how diverse it is. There needs to be greater recognition and understanding of the kinds of diversity residents are living in. Through explicit and simple maps and graphics, planners should highlight age, racial, ethnic, income and household diversity. The communication of this diversity should be simple, straightforward, colorful, graphic. It should be posted in well-traversed public spaces and places. Websites highlighting neighborhood diversity should make use of text, animated graphics, photos, and audio to tell the story of neighborhood diversity. B. Advertise what the kids are doing. Often, local schools and libraries are involved in projects about celebrating diversity. These efforts should receive wider exposure. Children are making art, writing poetry, and finding different means of expression of their cultural identities. They are encouraged to react to their differences with others in positive, affirming ways. Schools are regularly funding programs that build tolerance. Planners are in a position to spotlight these kinds of efforts to the broader community. C. Create a website of interviews. In city planning, technology has been blamed for dispersing and separating people where they were once interconnected in dense urban neighborhoods. Planners should explore the use of technology to play a role in reconnecting people in places that are diverse and disconnected. Through interviews with neighborhood residents representing varied population sub-groups, planners can use technology to find commonality. Planners can make use of technology as a “place” for exchange – an alternative mechanism for increasing the transaction base of a diverse neighborhood. Step Three – The Neighborhood Plan. Through a neighborhood charrette process, a neighborhood plan is produced. The process is open and inclusive. During the charrette process, planners identify and suggest opportunities to use design principles that stabilize and promote diversity: mix, connection and security. They talk about the importance of housing mix, business mix, facilities that support connection, the idea of breaking up enclaves. They consider nodes of new non-residential growth – strategically targeted in function of the housing diversity that surrounds them. They look for ways to intersperse different housing types, and at how codes can support the mix. They consider how strategically placed public investment can support diversity. Planners are there as a resource on design ideas, pointing out when and where specific ideas being proposed may have the effect of undermining diversity. Components of the plan The neighborhood plan emerging from this three-step process would likely focus on three ideas: a. shared management of the built environment as a community-building strategy; b. new types of codes that are flexible but also have an ability to preserve elements that stabilize diversity; and c. recommendations for targeted investment. Shared management. The neighborhood plan should implement ideas via a method of shared management of the built environment. Ongoing management should be directed toward putting in place an operating system that focuses on diversity preservation. 4 Codes. Codes are needed to harmonize “distinctive aesthetics, structures, and practices” found in socially diverse neighborhoods (Qadeer, 1997). There will be a variety of forms, facilities, housing types, and businesses to accommodate, and codes will be needed to provide both flexibility and some degree of cohesiveness. Targeted investment. Public investment – in public spaces, transit, and adequate facilities – is essential in diverse neighborhoods. In addition, mixed-income development will require public-private partnership since the market may be resistent. The same may be true of mixed use that is truly supportive of all levels of enterprise: the “natural tendency” of the market is chains and national markets. Public monies are needed to encourage small business retention, through microlending for example. 5