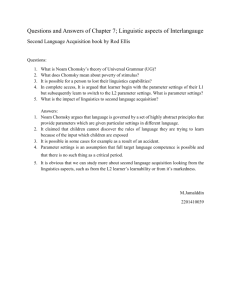

Introduction

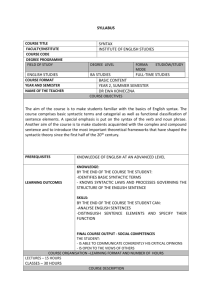

AN INTRODUCTION TO ENGLISH SYNTAX with applications to text analysis

Gloria Cocchi

Trieste, Edizioni Parnaso (2004)

Introduction

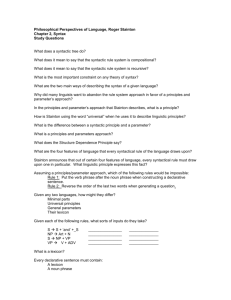

The Principles and Parameters Theory

This introduction will set the basis of the theoretical approach followed in this book, Generative

Grammar, also known in recent years as the Principles and Parameters Theory. This approach first originated as an attempt to give an answer to a puzzling question: how children are able to acquire languages perfectly (pathologies aside), in a spontaneous way and in a short period of time. Hence, we will start our discussion with some issues related to language acquisition, as well as with the presentation of the various theories that have been formulated to tackle this issue. We will finally opt for a cognitivist approach, which assumes the existence, in our brain, of a specific Language

Faculty, which governs language acquisition.

0.1. How we learn a language

The starting point of our analysis is the observation that all native speakers of a given language, independently of their cultural level and experience, are able to generate an endless number of sentences and phrases by combining the single elements together.

1 Furthermore, they are also able to give judgements on the grammaticality (or ungrammaticality) of various strings of these elements. This ability to give judgements seems to be highly intuitive; indeed it derives from one’s innate competence in the language, rather than from the knowledge acquired at school. This can be easily demonstrated thanks to some considerations. Firstly, little children, who certainly do not know the meaning of technical words such as subject , predicate , reflexive , etc., are also able to give judgements: they can, for instance, correct the mistakes made by foreigners speaking with them.

Secondly, part of the knowledge which characterizes the competence of native speakers is not the object of formal direct teaching at any level, as shown by the following examples:

1 Obviously we will abstract away from individuals with specific pathologies, such as deafness or language impairments

(disphasia, etc.), as well as from individuals with generic mental disorders.

(1) a Paul said that John admires himself b Paul said that John admires him

Any native speaker of English, however (un)educated, knows beyond any doubt that himself in (1a) refers to John and cannot refer to Paul , while him in (1b) may refer to Paul , or to any other male person present in the context, but certainly not to John . The reference of elements like him or himself is an example of that innate, untaught knowledge.

2

Crucially, one’s mother tongue is not part of the genetic inheritance, in the broad sense that a child will not necessarily acquire the language spoken by his natural parents.

3

To be more precise, although all human beings are born with the intrinsic ability to acquire languages (pathologies aside) - this is indeed one of the main features which distinguish humans from other animal species

- this intrinsic ability does not determine which particular language an individual will actually learn.

The language learnt by any baby is always the language spoken in the environment which surrounds him, and provides him with data; in other words, if the child of two English mother tongue people is torn away from his natural parents and brought to China, he will learn Chinese, and not English.

Furthermore, children who have been deprived of linguistic input from the environment will hardly acquire any language at all.

4

We are thus facing an apparent dilemma: children, whose general learning abilities are in most cases lesser than those of adults, are able to acquire a language (in principle any language) perfectly, spontaneously, in a relatively short period of time, without direct teaching or efforts, and at a very young age, at which, as said above, most other learning abilities have not matured yet.

This is something wondrous, especially when compared with the often imperfect results obtained when we learn a foreign language as adults.

5

In theory, adults should be at an advantage over children in the language acquisition process: their brains are more developed, their general learning abilities have completely matured, they already know a language perfectly (their mother tongue) and are often able to analyse it using technical terminology learnt at school, they know how to read

2 The reference of elements like him and himself will be discussed in details in chapter 11.

3 For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to child with the pronoun he , as the masculine form is traditionally employed as the default pronoun, when no sex specification is needed.

4 This was the case of deaf people, who were in the past labelled ‘deaf and dumb’, though dumbness was not due to a specific pathology, but was rather a consequence of deafness (i.e. of the lack of linguistic input). Even stories like

Tarzan’s, though legendary, are based on true cases of children lost in the forest at a very young age, who miraculously survived, though they had not learnt any human language, but rather some animal communication system (or no language at all).

5 The ‘critical age’ for language acquisition is considered to be around 12 years. After that age, we are still able to learn foreign languages, but we learn them ‘as adults’, namely in a non-spontaneous way, and with different modalities and results. Even children who have been isolated - for environmental reasons – from the community of speakers till that age, will learn their mother tongue as if it were a second language.

and write, and finally they may have been taught explicitly in the target language, with the help of books written by experts. In practice, adults learn a foreign language in a much longer period of time, with greater effort and time devoted, and with definitely imperfect results with respect to those obtained by little children acquiring their mother tongue,

6

especially if the learning process takes place in a spontaneous context (e.g. by immigrants). This is even stranger if we consider that in learning, for instance, mathematics, how to cook, or how to repair something, adults instead perform much better than children.

These considerations show that language acquisition is different from most other forms of ‘human’ learning, like the above-mentioned ones, and is instead more similar to the intuitive, instinctive type of learning which characterizes not only humans, but animals in general. For instance, in learning how to walk, or even to swim (special strokes aside!), a very young child is undoubtedly at an advantage over an adult. Therefore, though an articulated language like ours is something typically human, the process of language acquisition is something biological, instinctive, “animal”.

0.2. Different theories of language acquisition

The discussion contained in the previous section leads to the conclusion that the task of a linguist is not to teach a language, but to describe the innate, untaught competence a mother tongue speaker has, 7 as well as try to explain how children reach such a competence in a relatively short period of time. In this regard, several theories of language acquisition have been proposed; for the sake of simplicity we will mention only the two most important approaches, Behaviourism and

Cognitivism .

8

One of the earliest approaches used to tackle the issue of language acquisition in a formal way is called Behaviourism . This approach, which dates back to the first decades of the XX century, treats any form of learning, and verbal behaviour in particular, as the response to stimuli from the surrounding environment. The most important works based on this approach are Bloomfield

’s

(1933) Language and Skinner

’s (1957)

Verbal Behaviour .

6 Indeed, even when acquiring a foreign language, little children below the critical age perform much better than adults.

7 One could object that at school we are taught our mother tongue as well. Actually, children at school-age are already perfectly competent in their mother tongue, and are able to give judgements; what they are taught is a special register of their language, a standard or formal language, which is a sort of ‘artificial’ language (i.e. different from what people speak everyday) with specific rules, very similar to written language. Second language acquisition is a different issue; linguists are interested in this process as well, but only as far as it takes place in (more or less) spontaneous contexts, and by individuals who have not reached the critical age. Adult second language acquisition is by and large outside the field of formal linguistics.

8 The theories which may be grouped within either of these two approaches may of course partly diverge from one another. We will not take most of these differences into account, as this would go beyond the scope of this brief introduction.

Behaviourism hypothesizes a “stimulus-response-reinforcement” pattern at the basis of learning in general, and communication in particular. Hence, according to this theory, a child is prompted by a stimulus (e.g. hunger), which forces him to speak; what he utters is the response to the stimulus

(e.g. milk!

), and the (positive) reinforcement is provided by someone bringing him milk. In other words, one’s mother tongue is basically acquired by means of imitation : the child memorizes the link between some words heard/uttered in the appropriate contexts and the satisfaction of his needs.

This would explain the fact that a child will learn only the language(s) spoken in his environment, or no language at all in the absence of linguistic input, as hinted at above. Moreover, a child will not use words he has never heard. Language acquisition is thus the result of a habit formation process: linguistic competence will be built step by step, as the child’s needs become more and more complex, and at the same time he has memorized a higher number of words and clauses.

Though one cannot neglect the contribution brought about by Behaviourism in recognizing the fundamental importance of the environment, which provides linguistic input to the child, this approach has many drawbacks, which were first outlined in Chomsky’s (1959) criticism to

Skinner’s work, and will be briefly discussed hereafter.

To begin with, it is not always easy to trace back the stimulus which may have prompted a complex sentence, with no evident link to the context in which it is uttered. An out-of-the-blue remark, such as “ Amsterdam is a beautiful town ”, may be the response to many different stimuli. Vice versa, the same stimulus, e.g. an abstract painting, may prompt an endless number of different responses.

Secondly, imitation alone cannot be held responsible for the complex task of language acquisition

(cf. Cook 1988). Undoubtedly, children often produce ‘incorrect’ words and sentences, which they cannot have heard pronounced by adults. A case in point is that of ‘regularized’ past participles of irregular verbs, like goed or breaked : the frequent occurrence of examples like these (in all languages) proves that children do not simply repeat what they have heard, but spontaneously apply a ‘rule’ of past participle formation - which gives correct outputs in most cases! -, though nobody has taught them explicitly at this stage. The rule must therefore be innate.

Lastly, the input children receive from the environment is too limited to account for the construction of such a complex apparatus. This issue is generally referred to as

Plato’s problem

(cf. Chomsky

1986a), or the problem of the poverty of the stimulus . The input that a child is exposed to may in fact be inadequate, poor, and full of errors like false starts, hesitations or incomplete clauses.

Besides, the child soon becomes able to produce an infinite number of sentences, though the experience he has been exposed to is undoubtedly finite. Finally, a child may even forget part of the input he has received, as adults do: how often do we forget something that we have heard!

In order to explain the ‘mystery’ of language acquisition, taking into due consideration the problem of the poverty of the stimulus, as well as the other issues raised above, a different approach, labelled

Cognitivism (or Mentalism , or Innatism ) has emerged. The core hypothesis of this approach

(shared by the different theories which can be grouped under it) is that children do not start from zero in their learning process, but rather a great part of their linguistic knowledge is innate.

In particular Chomsky, the main representative of this approach, argues that there is a specific

Faculty of Language , situated in a specific area of our brain, which governs language acquisition

(as well as the subsequent linguistic functionality; cf. Chomsky 1986a, 1988). This thesis has been demonstrated empirically by data relating to people suffering from aphasia, who have lost (part of) their linguistic ability while adults, as a consequence of cancer, surgery, or any other type of traumatic event concerning the brain. Indeed, these data show that the loss of linguistic ability is the direct consequence of lesions in specific areas of the brain.

9

0.3. Universal Grammar – Principles and Parameters

In order to account for the fact that a child could in principle acquire any language, Chomsky argues that all of the natural languages in the world have many features in common; in other words, they must all be similar at a very abstract level, though superficially they may look very different from one another. In this regard, Chomsky assumes that the innate Faculty of Language situated in our brain contains a Universal Grammar (UG henceforward) - namely a grammar which is shared by all languages - which is composed of a certain number of Principles and Parameters . The task of the child acquiring his mother tongue is thus extremely facilitated: he will not have to start from zero, as a consistent part of the grammar he has to build is innate, and thus available prior to experience (Chomsky 1981).

10

The Principles encode the properties which are common to all languages, independently of their historical origin, and of which groups or families they belong to.

11

Among the Principles, we might include the fact that all languages classify words into specific categories (like nouns, verbs,

9 Indeed there are two distinct areas, where the Faculty of Language is situated; they are called Broca’s area and

Wernicke’s area, after the names of the two scientists who discovered them. Lesions in either of the two areas will result in the loss of different aspects of linguistic competence (see Akmajian et al. 1984, Cook and Newson 1996, for more details).

10 Obviously this helps account for the rapidity of the acquisition process, the lack of effort, etc., and compensates for the poverty of the stimulus.

11 Typological studies had already individuated properties common to all (or most) languages; Greenberg (1963) labelled them Universals .

adjectives and prepositions), 12 on the basis of their distribution within the sentence; all have concepts like subject and predicate , or transitivity ; all have strategies to form questions, give orders, make requests, negate something, etc. In the course of this book, and in particular in the first chapters, we will discuss many other (less intuitive) universal principles, such as the obligatory presence of the subject in all clauses (the so-called Extended Projection Principle; cf. chapter 2), and the internal structure of all types of phrases (X-bar theory; cf. chapter 3).

The Parameters are instead responsible for language differentiation, and in particular they encode syntactic variations. Actually, languages vary under many points of view. One might easily individuate the lexicon as the main area of linguistic differentiation. Undoubtedly, words are not innate and they must be learnt through experience: even as adults, we cannot possibly know the meaning of a word which we encounter for the first time, unless it can be inferred from the context.

13

Together with words, we also learn their idiosyncratic properties, and in particular their transitivity.

14

For example, a verb may be transitive in one language (e.g. English to phone somebody ), while its corresponding verb in another language may be intransitive (e.g. Italian telefonare a qualcuno ). Though all languages have both transitive and intransitive verbs (this is a principle), only experience will teach a child if a given verb is transitive or not in his mother tongue: as regards the specific example, he will have to learn – without being taught - if the verb in question must be used together with a preposition, as in Italian, or can be directly followed by its object, as in English.

However, language differentiation is certainly not limited to the lexicon in the broad sense, but involves syntax as well.

15 In particular, the theory assumes that, besides principles, UG contains a number of parameters referred to as binary choices. Thus, concerning specific phenomena, languages are left free to choose, but only between the two options provided by UG.

Perhaps the best-known example of a parameter is the Null Subject Parameter (see Chomsky

1981, Rizzi 1982, Jaeggli and Safir 1989), which will be tackled often in the course of this book.

Indeed, languages diverge with regard to the possibility for a subject pronoun to remain covert, i.e. silent. As shown below, some languages allow this possibility, e.g. Italian and Spanish in (2a),

12 Other categories, like articles or adverbs, may vary from language to language. As for Prepositions, these elements exist in all languages, though in some (e.g. Japanese) they follow rather then precede the name they accompany (eg: at school would sound like school at ); hence they are called Postpositions. The broad category is often referred to as

Adpositions, a term which is neutral with respect to word order.

13 The acquisition of lexicon was indeed one of the main issues supporting Behaviourism, as words are undoubtedly learnt from the environment.

14 For a detailed discussion of transitivity see chapter 2.

15 In this book we will abstract away from differences regarding phonetics/phonology (i.e. the sound system), and semantics (i.e. meaning). However, Generative Phonology and Generative Semantics assume that there are universal, untaught principles in these environments as well.

while others do not, e.g. English and French in (2b); in the latter languages the subject pronoun will always have to be spelled-out:

(2) a mangia la mela (Italian) come la manzana (Spanish) b he eats the apple (English) il mange la pomme (French)

The contrast in (2) is purely syntactic, and cannot be attributed to the lexicon, as was the contrast between the English to phone and the Italian telefonare , mentioned above. The presence of the subject does not in fact depend on semantic or idiosyncratic properties of the single verb: if a language allows the subject to remain implicit, this property will characterize all the verbs of the language, and vice versa.

Building on the input he receives from the environment, a child will thus have to fix the parameter , namely to establish which choice his mother tongue has made with respect to, for example, the (phonetic) presence of subject pronouns. The data on language acquisition show that, at first, all children tend to produce null subject clauses - at least with transitive verbs -, even those who are immersed in an environment where a non-null subject language is spoken.

16 In the latter case, children cannot possibly have received such an input (e.g. want milk ) from the adult speakers.

Data like these strongly support a cognitivist approach, as they show that children do not simply repeat what they have heard, as parrots do, but rather that their brain is able to generate unheard sentences on the basis of innate principles and parameters - with the words learnt through experience -, sometimes making choices which are different from those made by the target adult language (as in the case of English or French children producing null-subject clauses), provided these choices represent an option allowed by UG.

0.4. Levels of representation

The theoretical approach that we will adopt throughout the book originally stemmed from

Chomsky’s proposals put forth in the 1950’s and subsequently revised and even radically modified, both by Chomsky himself and by many other linguists that followed this approach (cf. Preface). In

16 The fact that transitive verbs are more often null-subject with respect to intransitive ones is due to the fact that, in the earliest form of syntax, children are able to combine only two words together. Thus intransitive verbs will appear with their subject, while transitive ones, which select for a subject and an object, will be combined with the object, and the subject will remain implicit.

particular, in this book we will adhere to a relatively recent version of the model, which integrates the important contributions that emerged in the Minimalist Program (Chomsky 1993, 1995). We will now briefly sketch some of the basic concepts which characterize this model.

Generative Grammar assumes that language is composed of two fundamental components, the lexicon and a computational system . The lexicon contains all the words in a language, together with the idiosyncratic information they carry with them: for example, if a given verb is transitive or not. According to a recent proposal (the so-called lexicalist hypothesis ), the lexicon also contains all of the inflected forms of a word, not only its stem and the various inflectional affixes (e.g. – s , ed ). In other words, according to this hypothesis a stem is combined with the inflectional affix in morphology , prior to syntax: the word enters the syntactic derivation when it is already inflected.

Among other things, this proposal overcomes the (purely morphological) problem that it is not always easy to separate the stem (i.e. the “semantic” part) and the inflection (the “grammatical” part) in a given form; for example, while an inflected form like walked can easily be analysed as the combination of the stem walk, and the simple past affix

–ed

, this cannot be done for a form like went .

The computational system is instead responsible for the structure of the sentence. With structure we do not mean only the linear order, but also – and more importantly – the hierarchical one, as will immediately emerge in the initial chapters of the present book.

Crucially, a sentence is built by selecting lexical items from the lexicon and merging (= combining, assembling) them together, two at a time; this operation is referred to as Merge . Merge is thus the simplest operation of sentence formation. To give an example, if we select the two lexical items

John and slept , we can build the following constituent via Merge:

(3) John slept

As we will see in the course of the book, syntax regulates the way lexical items can merge; in this specific case, we will account for the contrast between the string in (3), which is grammatical, and the ungrammatical one in (4), which might result by merging the same two elements in a different way:

(4) * slept John

However, sentences are not built by means of merging only: a syntactic derivation may also involve movement of a constituent which is already present in the sentence.

17 It is indeed intuitive that, in the examples in (5), the initial constituents have undergone movement:

(5) a This book I read (not that) b What have you read?

Indeed, in both examples the initial constituents ( this book and what ) represent the direct object of the verb read . In English, direct objects follow the verb, rather than precede it; the fact that, in (5), they surface at the left edge of the sentence reveals that they have undergone movement.

18

Therefore, syntax regulates the way the various constituents of a sentence can be merged and moved, in order to obtain a grammatical output.

An idea that has emerged since Chomsky’s early work is that every linguistic expression has several levels of representation . In particular, every expression is composed of an articulated string of sounds (the Phonetic Form ), as well as a logical-semantic interpretation (the Logical Form ).

19

Syntax is situated between these two levels and represents the intermediary, the link between the two systems; in technical terms, Syntax interfaces with both the Phonetic Form and the Logical

Form, as well as with the lexicon.

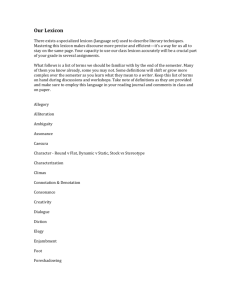

The following diagram illustrates the interrelations among the various components of language:

(6) LEXICON (+ MORPHOLOGY)

SYNTAX

Spell-Out

3

PHONETIC LOGICAL

FORM FORM

17 For a detailed presentation of the principles that regulate Movement, see chapter 4.

18 The derivation of these examples will be tackled in the course of the book.

19 Non-linguistic factors, such as the context, may contribute to the semantic interpretation of a sentence as well.

However, with Logical Form we only intend the interpretation which is exclusively linked to the syntactic structure, thus abstracting away from all extra-linguistic factors (see also Jackendoff 1972).

Chomsky’s early work also distinguishes a “Deep Structure”, where the lexical properties are projected, and a “Surface

Structure”, obtained through transformations (e.g. after movement has occurred). However, this distinction has been abandoned in more recent work (since Chomsky 1993), and we will not adopt it in the present book.

To be more precise, syntax picks up a certain number of (already inflected) lexical items from the lexicon and assigns them a (linear and hierarchical) structure, by means of operations of combination and movement, often referred to for brevity as Merge and Move . At a certain point, the derivation is sent to the Phonetic Form component, which converts it into sounds, and to the

Logical Form component, which converts it into meaning/interpretation. This point is referred to by

Chomsky (1993) as Spell-Out , i.e. the crucial moment in which the sentence, obtained by means of syntactic operations, is uttered.

After Spell-Out, no new lexical material can be introduced into a sentence via Merge, as it would be too late for it to be pronounced. In any case, Chomsky assumes that the derivation does not come to an end at Spell-Out, but continues at the level of the Logical Form ( LF henceforward). In particular, elements may undergo movement at LF as well. This movement will not be superficially visible (as the phonetic level has already separated from the derivation): it is a covert or implicit movement, which, however, will be constrained by all of the restrictions which are valid for overt movement

(cf. chapter 4).

20

Movement at LF takes place when a constituent needs to be logically interpreted in a position which is different from the one that it occupies in syntax. In the course of the book, we will present various examples of movement at LF. Interestingly, languages often parametrize on the level at which movement may take place; indeed, it often happens that the same type of movement occurs in all languages, but is syntactically visible only in some of them.

0.5. Summary

In this brief introduction we have sketched the main features characterizing the Cognitivist approach to language acquisition, which we will adopt throughout the book. Following Chomsky’s theories, we will assume that the mind of any human being contains a Universal Grammar , UG, which is composed of principles (universal properties, common to all languages) and parameters

(binary choices that languages are free to make). The existence of UG crucially facilitates the language acquisition process: indeed children possess an innate knowledge prior to experience, and their task will mainly consist in learning the lexicon of the language they are exposed to, and fixing the syntactic parameters.

We have also briefly discussed the structure of the theoretical model adopted in this book, often referred to as Generative Grammar . In particular, we have focussed on the important role of syntax , which acts as an intermediary between the other components of language:

20 Indeed, all the principles that regulate syntactic representations in general are still valid at Logical Form, which is thus a syntactic level of representation itself (cf. the discussion in Haegeman 1994).

lexicon/morphology on the one side, and phonology/semantics on the other. In other words, syntax takes inflected lexical items and assembles them together in order to obtain organized and wellformed strings of sound and meaning.

In the chapters which follow we will set the bases of language description according to the

Principles and Parameters Theory, with the aim of establishing which of the linguistic phenomena can be brought back to UG, thus representing universal properties, and what must instead be learnt through experience, and is peculiar to the single languages. We will base our discussion on English, but this language will be often contrasted with other languages, in order to show how phenomena that look different in different languages may be given a unique explanation, coming to the conclusion that a universal principle is involved.