Touring with Jane Austen - NSW Department of Education and

advertisement

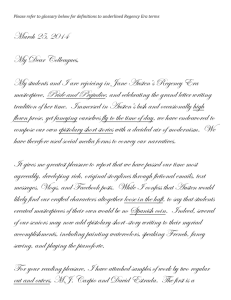

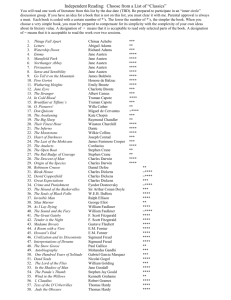

Premier’s Lend Lease English Literature Scholarship Regency romance meets reality TV— Jane Austen’s Regency world in the Regency House Party program Susan Stevens Gosford High School Sponsored by What most of us know about this period [the Regency 1811–1820] is gleaned from the literature of the time, in particular from its most famous novelist, Jane Austen.1 So said Caroline Ross Pirie, the series producer of the 2003 British reality show, Regency House Party. The stated aim of this series was to ‘bring the Regency back to life’ with its ‘dashing heroes and spirited heroines’ and to recreate the Regency world ‘down to the smallest detail.’2 The producers publicised their close links to Austen’s novels, especially this attention to detail that required their Mr Darcys and Elizabeth Bennets to shed all the vestiges of their 21st century lives as they took up residence in a 14th century ancestral home on the border between England and Wales. On the website advertising the series, Pirie went on to add that when looking for suitable candidates to participate, she wanted, ‘… the modern day equivalents of the people who feature in Jane Austen's popular novels—Pride and Prejudice, Northanger Abbey, Emma, Persuasion and Mansfield Park.’3 As the producer of other reality shows that relied on a specific historical basis, including Manor House, The 1900 House and 1940s House, Ross Pirie clearly has an interest in recreating the past and in representing it in a popular form that happily blurs the distinction between fact and fiction, reality and entertainment. Reality TV is the dominant genre of our time, and its aim to expose the private and closed by making it public and open appears at odds with the small 19th century domestic world of Austen’s novels. Added to this was the notion that the Regency world, with its emphasis on courtship and marriage in a highly stratified society, was represented in the series by just an assembly of 10 contemporary men and women, ‘to live and love as their Regency forbears had done.’4 So Jane Austen’s world apparently came back to life in 2003, not as an adaptation of one of her stories, but as a living, breathing ‘social experiment’, caught on television over eight episodes and with its own website at http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/regencyhouse/ In March/April 2006 I travelled to the United Kingdom to research how closely Austen’s world was represented in this series. The mixing of a canonical author and her 19th century world with 21st century popular culture proved an interesting and illuminating task. While not a fan of reality television, I agree with media expert James Friedman that its form cannot be ignored, as ‘no genre form or type of programming has been as actively marketed by producers, or more enthusiastically embraced by viewers, than reality-based TV.’5 On the other hand, after my investigation I cannot agree with a 2004 American review of the show that stated that the producers of Regency House Party ‘… seem to think if they just slap Jane Austen’s name on the project, it will give it some class.’6 Montage of scenes from Channel Four’s Regency House Party aired in 2003. Britain, culture, history and reality TV It was not until my study tour actually immersed me in the day-to-day life and culture of the British, that I became aware of their twin obsessions: their sense of their own rich history, and their love of reality television. And it is the latter that is most obvious in their popular culture. Reality TV dominates television schedules on all five free-to-air television stations, which offer programs as varied as Flog It, where an undercover auctioneer visits an area in order to find items to sell later at auction; Mind Your Own Business, which offers professional help to struggling family businesses, and You Are What You Eat, with a doctor who visits families and makes suggestions about their diets. Of course, there is also advice on how to tame the dog in It’s Me or the Dog, with animal behaviourist Victoria Stilwell; how to tame the children, with Super Nanny Jo Frost, and how to tame the house in Disaster Masters, with restoration experts. Even the news is interactive, using talkback television to provide more infotainment than information and analysis. It’s no wonder then that a show that combined both obsessions would be a winner in Britain. Regency House Party offered a nostalgic view into the private world of the very rich in the early 19th century—a time of magnificent architecture, beautiful ‘interior design’7 (a term first used during the Regency), rustic lifestyles amidst the unhurried social world of balls, garden parties, and ‘Rule Britannia.’ This show followed other House successes already mentioned, and belongs to a subgenre of reality television in that it represents a specific historical, political and social period where the house ‘guests’ (the cast), who do not know each other, are suddenly thrown together and have to live in the same environment for three months under very specific rules and regulations. Reality and television—mutually exclusive? Reality television is supposedly unscripted and unrehearsed, using ‘ordinary people’ and surveillance cameras to record any action taking place. It attempts to represent reality and, while it is very diverse—from Big Brother global formats to game shows and almost documentary style programs, the texts are all linked by their ‘discursive, visual and technological claim to “the real”.’8 Regency House Party was an expensive and lavishly produced television program which employed many of the conventions of reality TV. The narrative was driven more by soap opera than historical documentary, with its serialisation over eight weeks and character driven stories focusing on the emotional and controversial aspects of life in the house. Television cameras and three diary camera rooms recorded the day-to-day life in this manufactured situation, and clearly the editing of this material over a nine-week period into eight one-hour episodes helped to shape the audience’s perceptions of what was ‘real’. On the other hand, this type of program is proud of its historical basis, and without the Regency setting and environment, this house party would be little more than a lively and intelligent Big Brother. Certainly the series blended information and entertainment, and in many ways was a very ambitious project in attempting to take ten 21st century people and make them comfortable and happy living in an environment far removed from their own. However, the recreation of the Regency Period was closely researched and many of its social, economic and cultural aspects were as authentic as possible, allowing for our modern day and possibly nostalgic and romanticised viewpoint. Presenting the ‘real’ world of Jane Austen, Beau Brummell and Richard Brinsley Sheridan underpinned the whole series from beginning to end. And to a degree greater than I had expected, Regency House Party did bring aspects of Austen’s world to life. Selecting and preparing the house party guests Larushka Ivan-Zadeh, who played the highest ranking woman in Regency House Party, is in real life a countess, and she attributes her selection to this background. Her letter of confirmation pointed out that over 30,000 people had applied to take part in the project, partly supporting Ross Pirie’s claims that, ‘If the popularity of Jane Austen’s novels and their screen adaptations is an accurate gauge, it seems we yearn for the lost age of courtship and romance.’9 Of course, the possibility of becoming a television celebrity may also have something to do with it. The supporting package that was supplied to the selected applicants is illuminating. ‘What you are about to embark upon is an attempt to give TV audiences an inside view of what life was like for people involved in the mating game in Regency country house society. That world characterised in the novels of Jane Austen.’10 Chris Gorrell-Barnes was selected to be the highest ranking male of the house, the host in effect. His description in the literature pertaining to the show again reminds of the links to Austen. ‘Tall, dark, handsome, well-heeled and with an alluring hint of arrogance, Chris was a veritable Mr Darcy and would surely prove a source of considerable interest for all the female house-guests.’11 This is presumably the modern day equivalent of Austen’s famous quote about courtship and marriage: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.’12 The selection process complete, the preparation for the house guests in their early 19th century setting began. This included a detailed and exhaustive program on customs, manners and day-to-day living, all with the intention of ‘… making your Regency experience as authentic as possible.’ The sense of bringing history to life was also recognised in this early stage: ‘We have brought the best brains to the project … [but] none of the experts we’ve consulted have ever lived the experience as you will.’13 The amount of information needed to be learnt by each guest is intimidating. For women in the 21st century, much of what they read about their soon-to-be-transformed-to the19th-century lives must have appeared more daunting than romantic. The list included: modes of address, the rules of chaperonage, dining etiquette, placement and the rules of precedence, female deportment, toilet routines, dancing, letter writing, fans and the language of fans, religion, and so on. And these are only the major headings; under these came another set of rules and regulations for the ‘game’. In fact, over 55 pages of these very specific rules had to be followed in order to make the drama as ‘real’ as possible. All the information supplied was drawn from primary sources. Miss Bennet, I presume Once guests were dressed and ready to enter the Regency time zone they were each presented with a personal profile. This is not unusual in this type of program, where applicants are taking on a role which they are expected to maintain for the duration of the show. Reading the notes supplied to Larushka Ivan-Zadeh, however, it becomes clear that what made this profile more demanding was the need to transform, and in the words of the producer, hopefully ‘translate the person you are now into the person you might have been had you been a guest to our Regency house 200 years ago.’ Applicants were reminded again in this profile that they were playing a very specific role in the social environment of Austen’s Regency England, which was highly structured, and that their participation and cooperation were expected, as well as their decorum and gentility: ‘It is vital you understand the etiquette and protocol relevant to your position within the household.’ In Larushka’s case this was straightforward, as she was the highest ranking woman in the house due to her character’s ancient lineage. Born in 1784 into privilege, boasting Russian and French aristocracy in her family, and sporting a title, her rank reflects Regency England’s views on the class divisions which were deeply entrenched in family connections and wealth. Jane Austen herself is often critical of the upper class in her novels, but she also writes about a society that has limited social mobility and a strong sense of class consciousness. The Regency’s views on gender roles are also reflected in the characters’ profiles. Larushka’s character, Madame La Comptesse, had the title and breeding to make her a strong marriage candidate. She was well educated, well travelled and accomplished in all the arts expected of women at the time. What she didn’t have was any money. Social advancement for young men without property in the early 19th century was possible through the church, the military and, although frowned upon as somewhat vulgar, possibly a profession such as the law. None of these avenues were open to women, of course, which meant that the most important option for women to achieve a secure life was to make a successful marriage. And this is reflected in all of Austen’s novels. To fulfil her role, Larushka had to present an image of wealth, refinement and breeding, and hide her economic crisis from any prospective suitor. Again, this is quite plausible given that couples in this period would not have known each other very well before any engagement, and that once bound, separation or divorce almost impossible. Many of the ideas and characterisations of the different roles of the women represented in Regency House Party were borrowed from Austen’s novels, especially Pride and Prejudice.14 But Elizabeth Bennet, although impoverished and needing to make a ‘good’ marriage, is not the social equivalent of Madame La Comptesse. Miss Elizabeth Bennet would have been lucky to have been invited to such an elegant affair. And if the whole adventure was based on the Netherfield House party in Pride and Prejudice, it is worth remembering that Elizabeth was never invited there, and was only tolerated on sufferance in order to tend to her sick sister. Gorrell-Barnes and Ivan-Zadeh in their roles in Regency House Party. Meeting with Larushka, London, April 2006. Touring with Jane Austen As much has been made about the close relationship of this television show and the world of Jane Austen, a great deal of my study tour involved visiting the landscapes of Austen’s world. By ‘landscape’ I mean the wider definition that encompasses both the geographical settings and the social and cultural contexts. Austen’s landscapes are clearly established in her novels and they provide us with a clear and precise picture of the world in which she lived. Walking the streets of Bath and visiting the Pump Room, the Museum of Costume and the Assembly Rooms, the Jane Austen Centre and even an Indian restaurant set in a magnificent Regency ballroom, all contributed in a very real sense to the daily life of those in the early 19th century. The Museum of Costume has a section devoted to the Regency period, with beautiful white muslin dresses, perhaps just like those worn by Austen herself when she wrote in 1801: ‘I like my dark gown very much indeed, colour, make and everything. I mean to have my new white one made now, in case we should go to the [Assembly] rooms again next Monday.’ The Assembly Rooms to which she referred are now beautifully refurbished, and walking into them is like walking back in time and into an Austen novel. The rooms are large and well lit and built to easily allow for a general meeting place for both sexes, for the sake of ‘conversation, gallantry, news and play.’15 Kentchurch Court, selected as the home of the Regency House Party guests, is located on the border between England and Wales. While not a Regency House (it predates the 19th century), it did have sections renovated and redecorated in the Regency style to allow for as much authenticity as possible. Other areas in England offered further insight into the architecture and housing of the Regency. Lacock, a small village outside Bristol, was particularly interesting as it has been heritage listed and is as well preserved as any 200-plus-year-old town could be. It was used to film much of the 1996 television adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, as well as the latest film version of Vanity Fair. ‘Jane’ and I in Bath. Conclusions Jane Austen’s texts are an important part of our popular culture, but most people ‘read’ Austen through her screen adaptations and not her novels. When Pride and Prejudice was voted Australia's second favourite book in 2004, it was the 1996 series that was oft quoted by ‘readers’ and not the book. So ‘reading’ Regency House Party may well provide the audience with their only ‘real’ view of Austen’s world. If that is the case, then ‘readers’ will gain a great deal from this series. In a report such as this, the opportunity for detailed analysis is limited, but I have attempted to provide some understanding of the breadth and scope of my investigation. Regency House Party was a thoughtful and entertaining look at the early 19th century, and the insights into some of the more obscure customs and habits were instructive. It endeavoured to cover a great deal of territory in eight one-hour episodes, including romantic ideals, Regency food and health, medicine, science, male pastimes such as alcohol consumption, and the Hellfire Club, and had a colourful character in the form of a hermit living outdoors in the extensive lands. Many of these are not covered in Austen’s novels. Of course the show was shaped and constructed and did need to meet the expectations of a 21st century audience. The inclusion of a woman of African descent as one of the house party guests is an example of this shaping. Originally meant to be introduced in the last episode, her character as a woman of fortune was introduced in episode three once the series had gone to air due to viewer feedback. The whole idea of taking 21st century citizens back to the Regency is also a questionable process and the fact that none of the guests found their true love is testament to the artificiality of the situation. The female participants felt frustrated and bored by their daily lives in the 19th century, and this frustration was played out weekly on the diary camera. This was the one occasion when participants were allowed, even encouraged, to step out of their role. The men on the other hand appeared to enjoy greatly the experience, revelling in the power and attention and privilege that came with being a wealthy male in the 19th century. Links to teaching Regency House Party is related to the central idea of how meaning is made. ‘Reality television’ is an influential medium in popular and youth cultures, but it is a misnomer as it is clearly shaped and constructed. Any student would benefit from such a study. Naturally, the show lends itself immediately to the Extension 1 Course Texts and Ways of Thinking—The Individual and Society providing an insight into 19th century ways of thinking. It links to the Preliminary Extension 1 Course, Texts, Culture and Value where students are asked to examine texts from the past which have been appropriated into popular culture. It is related to the content and text requirements in Stages 4 and 5, which specify that students must have experience of social and cultural heritages, and literature from other countries and times; also the Additional Content, which asks students to respond to ‘significant’ historical texts. The current English syllabuses make explicit statements about information and communication technologies that need to be incorporated into teaching and learning. The result of this study would provide teachers with an innovative teaching and learning program that is integrated into the classroom. Modern technology brings to life a world seen by many students as arcane. The possibilities of quality teaching practices such as contact learning, collaborative learning and rich-tasking are endless. References 1. Jago, L, Regency House Party, p.7. Time Warner, 2004. 2. Ibid. 3. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/R/regencyhouse/ 4. Jago. p.7. 5. Holmes and Jermyn, Understanding Reality Television, p.1. Routledge, 2004. 6. http://www.realityblurred.com/realitytv/archives/historical_houses/2004 7. Jago. p.15. 8. Holmes and Jermyn, p.5. 9. Jago. p.7. 10. Notes supplied to Larushka Ivan-Zadeh by the series producer. 11. Jago. p.35. 12. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice, 1813. 13. Larushka’s notes. 14. The Museum of Costume, Assembly Rooms, Bath, Authorised Guide. 15. Ibid.