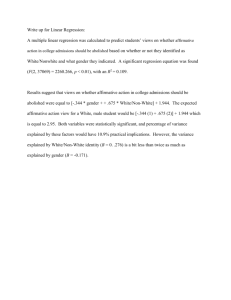

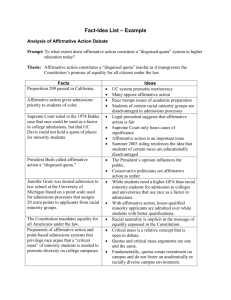

IMPLEMENTING AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

advertisement