BA Dissertation Guidelines

Department of History, Classics and

Archaeology

D ISSERTATION G UIDELINES

2013/14

BA H ISTORY

BA A RCHAEOLOGY

BA H

ISTORY AND

A

RCHAEOLOGY

2

Table of Contents

Part I: General Guidelines

Introduction

Procedures and Deadlines

Research and Writing-up: Planning ahead

What help can I expect from my supervisor?

Plagiarism Policy

Regulations for Submitting the Dissertation

Part II: Guidelines for Grammar and Writing Style

Part III: Guidelines on Citing Sources

Appendix: Dissertation Cover Sheets

3

4

6

7

8

10

11

16

21

3

P ART I: G ENERAL G UIDELINES

Introduction

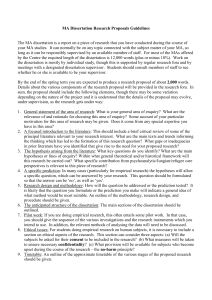

As part of your BA degree, you are required to submit a dissertation of 10,000 words

( including footnotes, but excluding the bibliography and appendices) on a topic of your choice, developed in consultation with an appropriate supervisor. Try to keep as close to the word count as possible: this is part of the exercise. The dissertation should be based on your own independent research. As such, it represents the culmination of your undergraduate studies and most students find the experience challenging and rewarding.

These guidelines outline the procedure for deciding on a topic and advise you on how to find a supervisor. They also explain the regulations for submission.

Parts II and III offer advice on grammar, writing style, and referencing.

Most students chose a subject that arises from a Group Two or Group Three course, choosing their supervisor accordingly. However, this is not mandatory. You must not replicate work that you have done in another course, but you can develop a topic that you have previously encountered. If in doubt, ask your dissertation supervisor.

In the BA History, BA Archaeology and the BA History and Archaeology degrees, the dissertation counts as one mark (out of a total of eleven marks) towards your final degree classification. Unlike marks from other courses, it cannot be discounted when working out your final degree grade. You must submit and pass the dissertation to complete the requirements of your degree otherwise you will not be able to graduate.

Your own research lies at the heart of your dissertation. It is not simply a long essay: it is a structured piece of analysis that aims to make a modest contribution to historical knowledge and debate. The dissertation shows that, at the end of your degree, you have the capacity to think and work independently: that you have become a scholar.

Often, the best dissertations ask a specific question. The question gives the argument direction and focus. This is not mandatory and, if you have the confidence to do it, addressing a statement can work just as well. Some examples from recent years include:

‘Social Transformations in the Archaeology of the West Country, 400-600AD’

‘A Comparison of Authorship: The Two Lives of St Radegund and Questions of Gender’

‘What Can the Court Rolls of Walsham le Willows Tell Us About Women’s Work and

Agency in Later Medieval England?’

‘Tudor London in the View of Foreign Visitors’

‘“Subject or Citizen?” The Impact of the French Revolution on Radical Politics in England in the 1790s’

‘Fighting a “Dangerous Obsession”: Rehabilitation and Repression in the Mau Mau Years’

4

Procedures and Deadlines

The Dissertations Coordinator for 2013/14 is Dr Sean Brady ( s.brady@bbk.ac.uk

)

If you have any questions about our procedures or deadlines, please contact Dr Brady.

Students will follow a dissertation research skills module in the spring/summer of their third year (part-time) and the autumn of their third year (full-time). Further details can be found here: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/history/current-students/undergraduateresources/level-4-modules

It remains the student's responsibility to make contact with their supervisor .

Although you have a free choice in your topic, it is strongly recommended that you select a topic that can be supervised by a member of staff in the Department. Details of the research and teaching interests of our staff can be found on our website: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/history/our-staff/

Friday, 18th October 2013, 5 pm : part-time, year four students : deadline for submission of coursework: dissertation title, dissertation proposal (300-500 words) and bibliography

(secondary and, where possible, primary sources) in a single document.

Friday, 29 th November 2013, 5 pm : full-time, year three students : deadline for submission of coursework: dissertation title, dissertation proposal (300-500 words) and bibliography

(secondary and, where possible, primary sources) in a single document.

Each student is required to submit one hard copy and upload an electronic copy to the module’s Moodle page.

Thursday, 1 st May 2014, 5pm: submission deadline for all dissertations

The dissertation must be submitted no later than this deadline.

Extensions cannot be granted for late submission. There is no grace period.

You are required to provide two hard copies and one electronic copy.

You are responsible for ensuring that your dissertation is completed and submitted by the deadline: ask the Office if you have any queries about submission.

Late submission and poor performance

All late submissions – whether late by minutes, hours, or days – are stamped ‘late’ by the office and capped at the pass mark of 40 (if the work is of a pass standard).

If your dissertation is late for reasons that were unforeseen and beyond your control, you can apply for mitigating circumstances. If you feel that you have under performed in your dissertation for reasons that were unforeseen and beyond your control, you can apply for mitigating circumstances. The Dissertations Coordinator can help you make an application.

Please note that the Committee is not empowered to change the mark (except in one instance, when your overall degree classification is borderline, and by no more than 2%).

5

If you are experiencing serious ongoing work, personal, or health problems that are affecting your work, you must speak to your supervisor and/or the Dissertations Coordinator. Ongoing problems are not usually covered by mitigating circumstances and we may need to discuss a course of action appropriate to your particular circumstances.

If, for any reason, you think that you may not be able to submit a dissertation in this academic session, you must speak to the Dissertations Coordinator. The earlier you speak to us, the easier it will be for us to help you.

The mitigating circumstances procedure is explained fully in the BA programme handbooks and on our website: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/mybirkbeck/services/rules/mitcircspol.pdf

You must consult the BA programme handbook and the Dissertations Coordinator if you wish to apply for mitigating circumstances.

6

Research and Writing-up: Planning ahead

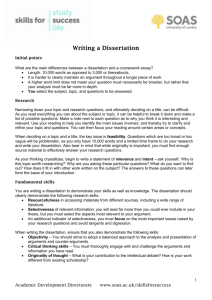

An undergraduate dissertation requires planning and organization. You need to devise a title that is tightly defined, so that you can complete the required research within the limited time available and also develop an interesting historical argument. Once you have done this, establish a feasible research/writing up timetable (in consultation with your supervisor) in order to avoid a last-minute crisis.

Always remember to save your work and back it up in more than one location: we cannot guarantee that mitigating circumstances claims for lost work will be accepted.

To help you build your bibliography, you should explore the numerous online catalogues and databases available via the College E-library: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/elib/ Assistance with building a bibliography by using citation indexes and databases is available from the history subject librarian, Dr. Aubrey Greenwood (E-mail: a.greenwood@bbk.ac.uk Phone: 020 7631

6062).

The library has also produced a useful list of books and websites that provide further guidance on writing dissertations, with advice on doing research, writing-up and citing references. For these details see: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/subguides/studyskills One text that is specifically intended for students writing undergraduate dissertations is John Young & John Garrard, How to write a dissertation (Salford, 1993).

As you do your research, be sure to keep accurate notes and references for all the material you consult. Make a note of all the publication details of books and articles that you use and keep an accurate record of pages consulted. You should also keep a detailed record of any primary sources you use. These practices will help you to avoid plagiarism (see below).

Dissertations are normally based around a core of original research into a body of primary sources : for example, newspaper articles, parliamentary papers, private letters and/or diaries, archaeological site reports, learned treatises, medieval chronicles, judicial trial documents, business records, missionary archives, oral interviews, government reports and correspondence. Dissertations analysing physical objects, images, or paintings are also acceptable. You can discuss what to use and how to use your sources with your dissertation supervisor. In general, primary sources support your argument and provide the evidence on which to base assessments and conclusions. Try to avoid long quotations and always make sure you discuss their significance.

Your dissertation should be situated within the relevant historiography . Simply summarizing the views of different historians will not gain you good grades. You are aiming to provide a critique of the secondary material that shows your awareness of key debates in the field, your ability to weigh up competing arguments, and your sense of inconsistencies or gaps in our historical knowledge. Your supervisor will be able to advise you about suitable readings, but you are also expected to seek out your own material. A good dissertation will use a wide range of general and specialist readings, and display awareness of the most up-to-date research in the field. Use the footnotes and bibliographies in your general reading to strengthen your bibliography: search engines such as the Bibliography of British and Irish

History will also help.

7

There are some occasions when the line between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ source can be blurred. You could, for example, attempt a critical analysis of the historiography of a topic, by placing the relevant historians into their own intellectual, social, political and cultural backgrounds. In this case, the historiography becomes the primary source – you should aim to present a new interpretation of this body of scholarship by developing original analytical questions. This approach, again, is something to be carefully worked out with your dissertation supervisor. In the normal run of things, however, the best course is to identify an available body of primary source material that is not too overwhelming, and use it to provide your own analysis in relation to whatever wider area is relevant.

When you reach the writing-up stage, be aware that the dissertation needs a structure. It should have an introduction that explains the topic you are addressing, and briefly sets out the historiographical context: explain why your topic is important and show how it relates to the work of other historians. You may also wish to include a short section on your sources : why you have chosen them, what they can tell us, and any problems they may present for the historian. The main body of the dissertation should develop a clear argument that presents evidence and takes your historical analysis forward in a coherent and logical fashion.

Dividing the main body into three or four chapters or subsections , addressing different aspects of the topic, helps to give the dissertation focus and direction. The conclusion should briefly recapitulate the specific historical problem considered in your dissertation and reflect upon your key findings. It is here that you will prioritise your evidence and present your own evaluation of your topic. Do not introduce new material here. Make sure that your conclusion relates to the main arguments and follows on logically from the points you have already made. Any tables or images , whether integrated into the text or placed in an appendix, must be referred to in the text.

A good introduction and conclusion are important. Your introduction should ‘signpost’ your main arguments – tell the reader what you are doing, do not leave them guessing! Likewise, the conclusion should show the reader that you understood the demands of your topic.

Before you hand in : Check your final draft for errors of fact, spelling, punctuation, footnote/endnote numbering and typing errors before it is submitted. Scholars adhere to basic conventions that are designed to make it easy for people to read and understand their work: your dissertation must adhere to these basic standards. Even if you have spell-check facilities on your computer, they are no substitute for your own proof-reading. Careless presentation will be taken into account by the marker.

What help can I expect from my supervisor?

The Department will allocate supervisors for all students who submit their assessment for their Research Skills for Dissertation module. Remember that it is your responsibility to make contact with your supervisor.

You are expected to use your own initiative in conducting research and seeking meetings with your supervisor. Students and supervisors will work out how much face-to-face and/or email contact is appropriate but, as a general rule, you can expect to meet three times with your supervisor: ideally, once at the end of Year Three, once in the autumn term of Year Four and once in the spring term of Year Four. Full-time students ideally should meet with their

8 supervisors three times, late in the autumn term (toward the end of the Research Skills for

Dissertation module), and twice in spring term of the final year.

Your supervisor will give you feedback on plans and draft chapters, but you should be aware that your supervisor is not obliged to read an entire draft of your dissertation. If you would like your supervisor to comment on written work, be sure to give them advance notice and, more importantly, enough time to read your work and enable you to make changes. Many students find it helpful to ask for feedback in advance of the Easter break, thereby enabling them to use their supervisor’s recommendations to produce a final draft over the Easter break.

Please be aware that your supervisor may not be available, personally or on email, over the

Easter break. Try to make sure you have communicated with your supervisor before the end of spring term in your final year.

For more information about supervision, see the College guidelines: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/mybirkbeck/services/rules/Dissertation%20Supervision%20Policy.pdf

Remember: we are here to help you. Never be afraid to ask.

Plagiarism Policy

What is plagiarism? Plagiarism is the publication of borrowed thoughts as original, and it is the most common form of examination offence encountered in universities. Some students plagiarise unintentionally, through ignorance of what constitutes plagiarism. Yet, even if unintentional, plagiarism will still be considered a serious examination offence. Common forms of plagiarism include:

copying the whole or substantial parts of an essay or dissertation from a source text

(such as a book, journal article, web site or encyclopaedia) without proper acknowledgement;

paraphrasing another person’s work very closely, with minor changes but with the essential meaning, form and/or progression of ideas maintained;

procuring the whole or parts of an essay or dissertation from a company or an essay bank (including websites);

submitting another person’s work as one’s own, with or without that person’s knowledge;

submitting an essay or dissertation written by someone else and passing it off as one’s own;

re-submitting work that has been previously submitted for another course (i.e. selfplagiarism).

In all written work, sources must be properly documented and referenced. For example, every quoted passage taken directly from the work of another has to be clearly marked as such by the use of quotation marks. The full reference, including page number, should be given for each such quotation. In addition, all paraphrased material should be appropriately used and cited. There are, of course, some common-sense exceptions, such as familiar proverbs, wellknown quotations or common knowledge. If in any doubt, the golden rules are :

give the reference (and be accurate and consistent)

9

ask your tutor for advice on correct citation practices. Course lecturers and tutors will be able to answer any particular queries.

For further information, you can consult the library website

( http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/subguides/generalref/Citations ), which provides links to citation guides on the web (including advice on how to reference information taken from websites).

In addition, you can also explore the information collected by the national Plagiarism

Advisory Service ( www.plagiarismadvice.org

).

Procedures

The Department adheres to a universal set of regulations that have been set by the College. To ensure that students are aware of the seriousness of plagiarism, each piece of submitted work

(that is, all essays and the dissertation) must be accompanied by a declaration signed by the student, which certifies that the student is familiar with the School policy on plagiarism and that the work being submitted is her or her own.

Penalties

Plagiarism undermines the entire basis for academic awards given to students. This is why the

University, the College and the School take it extremely seriously. Plagiarism will not be tolerated and is treated as a serious disciplinary matter. Action will be taken wherever plagiarism is suspected – and plagiarism is not difficult to detect. In these cases, students will receive a formal letter from the department, outlining the disciplinary proceedings for dealing with cases of suspected plagiarism, as well as possible penalties.

If plagiarism is confirmed, penalties will be imposed according to our regulations. Students have a right of appeal in all cases.

For further details on Birkbeck’s College Policy on Assessment Offences , including plagiarism, please visit http://www.bbk.ac.uk/reg/regs/assmtoff

10

Regulations for Submitting the Dissertation

You must submit

TWO HARD COPIES plus ONE ELECTRONIC COPY

Both must be received by 6pm on Thursday, 1 st May 2014

Your dissertation must be formatted as follows:

typed or word-processed in black ink on one side of A4 paper

double-spaced with wide margins (minimum one inch on both sides)

a standard font (Times New Roman, Courier, Arial) and size (11 or 12 point)

all pages, except the title page, numbered

Hard copies should be bound securely by spiral or heat binding. We cannot accept dissertations submitted in a loose-leaf folder or ring binder.

Electronic copies must be submitted through our Virtual Learning Environment i.e. Moodle.

Students will be fully instructed on how to upload submissions before the deadline. Do not email copies to your supervisor: they are not responsible for receiving your submission.

The dissertation is deemed to have been submitted once the electronic and hard copies have been received. If you have any queries or concerns about submitting your dissertation, you must consult the Office in good time before the deadline.

Please keep an electronic version of your dissertation. Please note that the Department reserves the right to award a mark of zero (0%) for a dissertation in cases where students do not make available an electronic copy.

Title Pages: You need a different title page for each copy of your dissertation, they can be found at the back of this booklet or can be downloaded from our website. The title page on one copy should be the signed ‘Dissertation Cover Sheet A’, which certifies that it is your own work and declares the word length. The title page on your other copy should be

‘Dissertation Cover Sheet B’ which will provide your candidate number, the title of your dissertation the name of your degree. This second title page must omit your name to enable anonymity in examining. The title pages should be included in the binding of the dissertation.

The title page of your dissertation should declare its word length . Dissertations that are excessively long can be rejected, which will make it difficult for you to finalise your studies.

The word limit excludes titles, diagrams, tables, the bibliography and simple references but includes discursive footnotes and appendices that expand the text. At the other end of the scale, excessively short dissertations, as well as those using extended quotations to ‘pad out’ the narrative, can also be rejected.

Bibliography: All dissertations must include a full bibliography listing all the sources you have consulted.

11

P ART II: G UIDELINES ON G RAMMAR AND W RITING S TYLE

English rules of grammar must be followed. If you need to know more about rules of grammar, consult the following.

Burchfield, R.W. (ed.),

The New Fowler’s Modern English Usage

, 3 rd edn. (Oxford: OUP,

1998)

Greenbaum, S. The Oxford English Grammar (Oxford: OUP, 1996)

Ritter, R.M. The Oxford Guide to Style (Oxford: OUP, 2002)

Abbreviations:

Avoid using abbreviations such as Gen. Haig, Cpl. Schulze, e.g., i.e., etc., in the main text of your dissertation. You can abbreviate titles and archive locations used in your footnote/endnote references and then list them on a separate page. For example:

AHR American Historical Review

JAH Journal of African History

P&P Past and Present

PP Parliamentary Papers

PRO Public Record Office, Kew, London

BL The British Library

Apostrophes:

Apostrophes denote possession. They are not used in plurals. Thus:

General’s = belonging to the general

Generals = more than one general

Generals’ = belonging to the generals

There is no apostrophe in plural dates. Thus, write 1960s, and not 1960’s.

The main exceptions to the above are:

Its = belonging to It

It’s = It is

Whose = belonging to Who

Who’s = Who is

Possessive pronouns also do not have an apostrophe:

Ours = That thing belonging to us (The land is ours)

Theirs = That thing belonging to them (Theirs was an unhappy fate)

Yours = That thing belonging to you (My book is older than yours)

Capitalization:

Initial capitalization (i.e. placing the initial letter in the upper case, or capital letters) should be kept to a minimum. Capitalize magnetic directions only when part of a recognized name; thus, North America, but northern England. A similar rule (capitalize nouns as part of recognized compounds) applies to the names of states; thus, ‘The British Empire’, but ‘the empire of the British’. A convention has emerged that general historical periods are not capitalized (medieval, early modern, modern) but archaeological ones are (Neolithic, Iron

Age). For titles of persons, use capitals where the title is immediately followed by the name of the person. Do not use capitals where the title stands alone. Thus use capitals in the case of

‘King George III of England’ and ‘President Lincoln of the United States’, but not in the case of ‘George III, king of England’, ‘Lincoln, president of the United States’.

12

Do not employ general capitalization (placing the whole word in capitals) for technical terms; these should be underlined or italicised. Never use general capitalization for names. You should not write, for example, ‘the main supporter of this bill in parliament was a Mr.

PORTILLO of ENFIELD.’

Commas, colons and semi-colons:

Commas should be used to separate items in a list (thus, ‘lock, stock and barrel’), to separate adjectives where more than one is used, if appropriate to the sense (thus, ‘a proud, hasty man’) and to improve sense, generally by isolating the main clause from subordinate clauses.

Thus: ‘First of all, we might consider how housework was seen by the popular press.’ Here, the comma separates the introductory sub-clause, from the main body of the sentence.

‘In the seventeenth century, sailing ships were small, smelly things.’ Here the comma separates the dating sub-clause from the main body of the sentence, and, in doing so, clarifies the meaning of the sentence. If it had read, ‘in the seventeenth-century sailing ships were small, smelly things’, would that mean that there were small, smelly things in the sailing ships of the day.

Semi-colons may be used similarly to separate items in a list, where the list comprises short phrases rather than single words. Thus:

‘The aims of this dissertation are many: to consider the role of housework in the nineteenthcentury economy; to discuss the extent to which housework was defined as a purely female sphere; and to question whether the status of women changed in this period.’

A semi-colon may also be used where you have two statements or main clauses and you wish, stylistically, to stress the fact that the two are linked, without employing a conjunction. Thus:

‘When he went to Hawaii, Captain James Cook hoped to achieve glory and renown; it was, alas, not to be.’

The sentence is, in actuality, no better than either of the following:

‘When he went to Hawaii, Captain James Cook hoped to achieve glory and renown, but it was, alas, not to be.’

‘When he went to Hawaii, Captain James Cook hoped to achieve glory and renown. It was, alas, not to be.’

It does, however, make for stylistic effect and variation. Note that the clause separated from the main clause by the semi-colon would stand alone as a separate sentence.

Colons are used to introduce lists or distinct examples (as throughout these guidelines). The colon can thus be used in a similar way to the semi-colon to link concepts. Thus:

‘Only one thing stood in the way of the king’s final triumph: the enormous influence of his younger brother.’ Note that the separated sub-clause here cannot stand-alone (it has no verb).

In a sense, it replaces a verb and conjunction or a full stop. You might instead have written either of the following:

‘Only one thing stood in the way of the king’s final triumph, and that was the enormous influence of his younger brother.’

‘Only one thing stood in the way of the king’s final triumph. It was the enormous influence of his younger brother.’

Again the purpose is stylistic rather than grammatical.

Colloquialisms and informality:

Avoid colloquialisms and colloquial forms of expression, at all times. Steer clear of judgements and personal opinions that you cannot substantiate, such as ‘Queen Victoria was a megalomaniac’, or ‘Emperor Nero was an unbalanced psychopath.’

13

In the formal language of historical writing, you should not use contractions such as don’t and couldn’t. These should be spelled out fully as ‘do not’ and ‘could not’.

Dates:

Centuries should be written in full as twentieth century, rather than 20th century.

Do not use ‘the 1800s’ for ‘the nineteenth century’; it is confusing, since it could also mean

‘the decade 1800-1809’, in the same way that ‘the 1860s’ means ‘the decade of 1860-1869’.

Note: a hyphen is used when the time period is descriptive, e.g. ‘nineteenth-century houses’ but not ‘houses in the nineteenth century’.

Dates should be given in the following form: 31 August 1969.

Hyphens:

Try to avoid using hyphens, instead of commas or brackets, to mark off subordinate clauses.

Above all, a comma never follows a hyphen. This, for example, is gibberish: ‘King Abiodun took his court, including the chief of Ilorin – who was dying –, to Oyo.’

This would be acceptable: ‘King Abiodun took his court, including the chief of Ilorin, who was dying, to Oyo.’

So would this: ‘King Abiodun took his court, including the chief of Ilorin (who was dying), to

Oyo.’

May and might:

There is an important distinction between these, but also an unclear area where either could be appropriate.

The main point to remember is that if you are referring to something that was once a possibility but did not in fact happen, you should use might. Thus:

‘Given enough support at the right time, the Aztecs might have defeated the conquistadors.’

(As we know, they did not).

On the other hand, it is correct to say ‘The Aztecs may have hoped for greater support from their neighbours’, since this remains uncertain.

Names:

Be consistent. Use recognized Anglicized versions of names if at all possible. It is pretentious to talk of Alexandros, Felipe II or Napoleone Buonaparte rather than Alexander, Philip II or

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Numbers:

All numbers below one hundred should be written out in full. Numbers over one hundred should be given as arabic numerals. Thus, ‘only fourteen of the 146 original members of the expedition returned unscathed, but a further twenty-two wounded straggled in over the next four weeks.’

Exceptions include numbers including a decimal point, and percentages. Thus, ‘the rise in unemployment in this period was no less than 13.24 per cent’

Quotations:

A quotation should be enclosed within single quotation marks, unless it is very long (more than forty words) in which case it should be indented. Quotations within quotations should be indicated by double quotation marks, thus:

14

As one historian comments, ‘we would do well to remember Birkbeck’s famous statement that “when a student studied, it was frequently part-time.”’

The quotation of foreign languages should always be given in translation in the text. The original should then be given in a note that permits the reader to check your accuracy.

Do not put quotations in italics . This is unnecessary.

Sentence construction:

All sentences must convey a self-contained ‘meaning’. The main clause should be capable of standing alone and conveying the sense of the sentence. You should note that conjunctions

(pay special attention to ‘although’, ‘though’, ‘despite’, ‘whilst’, and ‘while’) only introduce part of a sentence. These are not sentences because they cannot stand-alone.

‘Although, in June, the king went on campaign.’

‘Because he was suffering from dysentery at the time.’

This is a sentence: ‘Although, in June, the king went on campaign, the commander-in-chief was unable to join him because he was suffering from dysentery at the time.’

Clauses introduced by most conjunctions are ‘subordinate’ or ‘conditional’, which is to say they require a ‘main clause’ (with a main verb and subject) to complete the sentence. In the case above, the main clause is actually ‘the commander-in-chief was unable to join him’

(which, you will note, makes perfect sense standing on its own).

Occasionally, you will note that writers use ‘co-ordinating’ conjunctions (and, but, so) to begin sentences. Thus:

‘The Polish government retaliated by expelling three German businessmen. And so it went on.’

‘At this point Churchill thought he had brought the matter to a close. But it was not to be.’

This is grammatically incorrect, but sometimes ‘works’ for dramatic or emphatic effect.

However, this is so difficult to get right that it is best to avoid altogether. In the two examples given above, a comma could simply replace the full stop.

Spelling:

Make sure that there are as few spelling errors as possible before you submit the dissertation.

English spellings should always be employed (colour rather than color; travelled rather than traveled; axe rather than ax; and so on). As an exception, words such as organization, organized and organizing may be spelt with an ‘s’ instead (organisation, organised, organising), provided that you are consistent throughout. In short, always follow the spelling of the Oxford English Dictionary

. Note the rule of ‘c’ for noun, and ‘s’ for verb, for example: advice/advise. Also, adverbs ending in ‘-ily’ have one ‘l’ (satisfactorily; easily); those ending in ‘-ally’ have two ‘l’s (factually; partially).These are some other common mistakes:

Lead: metal; led = past tense of verb ‘to lead’

Effect: verb. To make something happen. ‘She effected a remarkable change in policy’

Effect: noun. A result or consequence. ‘The effect of the change was remarkable’

Affect: verb. To produce an effect (noun). ‘The change affected her colleagues greatly’

Practice: noun. Sharp practice; the practice of government.

Practise: verb. He practised the violin every day.

Split infinitives:

There is disagreement on split infinitives, but many people think they should be avoided. ‘To go boldly’ or ‘boldly to go’ are acceptable, but ‘to boldly go’ is not.

15

Tenses:

The simple rule for the appropriate tense is this. If it happened in the past, use a past tense.

There is one major exception, which refers to what is in a document. ‘The Treaty of

Versailles states clearly that ....’ If you read it, the Treaty of Versailles still states clearly whatever it is supposed to contain. It is acceptable to extend this present tense to the writer, where he or she is, so to speak, in the act of writing. For example:

‘In the preface to

Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism

, Lenin writes that ‘...’. These, however, are the only exceptions.

Underlining and italicizing:

1. In the text:

Underlining or italicizing should be used for foreign technical terms and titles, and for foreign phrases that have not become ‘naturalized’ into the English language. Consult a good dictionary for guidance. Do not underline the names of people or places, unless, in the latter case, you are drawing attention to an alternative, archaic, technical or foreign form. Thus, ‘the

Greeks set up a trading colony at Naples, or Neapolis .’

Do not use underlining or emboldening for emphasis. You should word your sentences in such a way as to carry the emphasis without highlighting.

2. In footnotes (or endnotes) and the bibliography:

Underline or italicize the titles of printed books and of journals/periodicals; do not underline the titles of articles.

16

P ART III: G UIDELINES ON C ITING S OURCES

Your dissertation must attach a complete bibliography of all the material consulted, and provide references for the exact source of quotations and other specific points taken from your sources. If you have used both primary and secondary material, your bibliography should be divided into two separate sections to reflect this. Moreover, under these headings, you could separate printed primary sources from those in archive collections, or separate primary sources by type (for example, newspapers, published memoirs, parliamentary papers and so on). Published secondary sources such as books and journal articles should be separated from unpublished secondary sources such as Ph.D. theses and seminar papers. Look at the format used in the bibliography of a book dealing with your topic to give you an idea of how to set out your own bibliography.

There are two acceptable methods of citation. The first provides references in the form of footnotes or endnotes and is known as the Oxford System. The second incorporates references into the main text using brackets and is called the Harvard System. These two methods are explained in the guidelines below. However, these guidelines are not intended to be comprehensive and you are strongly advised to refer to a style manual for specific advice.

Keep two important points in mind. First, choose one style and be consistent. Do not merge features of the Oxford and Harvard citation methods. Second, be sure to enter citations as you write-up your dissertation. Do not plan to insert them after you have finished writing-up. Not only is this an extremely tedious job, it makes the likelihood of error much greater.

Detailed online guides explaining how to cite sources are available through the Birkbeck

College Library website at: http://www.bbk.ac.uk/lib/studyres.html

Helpful and concise texts for further guidance are:

G. Harvey, Writing with Sources: A Guide for Students (Indianapolis, 1998)

K.L. Turabain, A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses and Dissertations 6 th edn.

(Chicago, 1996).

More detailed and comprehensive texts are:

Butcher, J. Copy-Editing: The Cambridge Handbook for Editors, Authors and Publishers , 3 rd edn. (Cambridge, 1992)

The Chicago Manual of Style , 14 th edn. (Chicago, 1993)

Gibaldi, J. and Achtert, W.S. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers , 5 th edn. (New

York, 1999)

MHRA Style Book: Notes for Authors, Editors, and Writers of Theses , 5 th edn. (London, 1996)

Ritter, R.M. The Oxford Guide to Style (Oxford, 2002)

The Oxford System

References are placed in notes, either at the foot of the page (footnotes) or at the end of your dissertation (endnotes). These notes are identified in the text by a number, placed after punctuation, thus:

This was widely believed to have been ‘brought about by witchcraft.’ 1

Word-processing programs such as Microsoft Word and WordPerfect have a facility that makes it easy to insert a footnote or endnote reference number into text. The software enables

1 Sueann Caufield, In Defense of Honor: Sexual Morality, Modernity and Nation in Early-Twentieth

Century Brazil (London, 2000), 22.

17 you to choose between using footnotes or endnotes and does the formatting for you.

Nevertheless, if you find this difficult, place the number of the note in brackets, thus:

This was widely believed to have been ‘brought about by witchcraft.’(1)

If you do this you will need to use endnotes. These should be listed at the end of your dissertation, under a heading such as References Cited or Endnotes. Begin the listing on a separate page between the main text and your bibliography.

When you make a second citation of a particular text, the full details can be abbreviated. Thus a second citation of Caufield’s book would be:

Caufield, In Defense of Honor , 27.

If exactly the same text and the same page are cited in the next reference, the Latin abbreviation Ibid can be used. It should be italicised or underlined, following the format for book or journal titles. If you refer to a different page of the same text write, Ibid ., p. 45.

However, avoid use of the Latin term op.cit.

because it is often difficult to trace a reference back through the dissertation. Use an abbreviated reference instead.

Journal articles should be initially cited in the form:

Sharon Musher, ‘Contesting “the way the Almighty wants it”: Crafting memories of ex-slaves in the slave narrative collection’, American Quarterly 53 (March 2001), 2.

A second citation of this article would be:

Musher, ‘Crafting memories’, 19.

Chapters in books should be cited in the form:

Robert Ross, ‘The Cape of Good Hope and the world economy, 1652-1835’ in Richard

Elphick and Hermann Giliomee (eds.), The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-1840

(Cape Town, 1979), 253.

A second citation of this chapter would be:

Ross, ‘The Cape and the world economy’, 267.

Unpublished theses should be cited in the form:

Timothy Keegan, ‘The Transformation of Agrarian Society and Economy in Industrializing

South Africa: The Orange Free State Grain Belt in the Early Twentieth Century’, (University of London Ph.D. thesis, 1981), 44.

When you write out your bibliography, your references should be in alphabetical order of the author’s surname, with works by the same author in chronological sequence of the publication date. As for reference notes, all titles of books and journals must either be underlined or italicized , but article titles and book chapters are in inverted commas. You must provide the page numbers for journal articles and book chapters. The punctuation is also slightly different, in that full stops are used instead of commas. Thus a bibliography of all the published sources cited above would be:

Caufield, Sueann. In Defense of Honor: Sexual Morality, Modernity and Nation in Early-

Twentieth Century Brazil . (London, 2000)

Musher, Sharon. ‘Contesting “the way the Almighty wants it”: Crafting memories of exslaves in the slave narrative collection’. American Quarterly 53 (March 2001): 1-31.

Ross, Robert. ‘The Cape of Good Hope and the world economy, 1652-1835’ in Richard

Elphick and Hermann Giliomee (eds.). The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-

1840 (Cape Town, 1979): 243-280.

So far, only secondary sources have been used as examples. Some sample primary source citations are as follows:

18

Newspapers

Alan Lee, ‘England Haunted by Familiar Failings’, The Times , 23 June 1895.

If the article is unattributed, list it under the title:

‘Hiroshima’, The Manchester Guardian , 31 August 1946.

Section, page and column numbers can be included for a more precise reference. This is useful if you refer to more than one article in the same edition:

‘September 11 and Beyond’,

The New York Times , 15 September 2001, sec. 2 p. 7, cols. 2-3.

Edited letters, diaries, memoirs and document collections

Virginia Woolf, Letter to Emma Vaughan, 12 August 1899. Congenial Spirits: Selected

Letters of Virginia Woolf , ed. Joan Banks (San Diego, 1989), 5-6.

Jeremiah Greenman, Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution, 1775-1783 ed.

Robert C. Bray and Paul E. Bushnell (DeKalb, 1978), 56.

Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the People in London , (London, 1892-7), Vol. II, 21-22.

Booker T. Washington, Up From Slavery: An Autobiography (1901; rpt. New York, 1978),

34.

Edward Bean Underhill, The Tragedy of Morant Bay: A Narrative of Disturbances in the

Island of Jamaica in 1865 (London, 1895), 5

H.T. Bourdillon, ‘Minute On Differences Between British and French Colonial Policies’, 21

April 1954, CO 936/327, [Extract]. Document 119. The Conservative Government and the

End of Empire, 1951-1957: Part I International Relations ed. David Goldsworthy. British

Documents on the End of Empire Series (London: HMSO, 1994), 314.

Ancient and medieval writers

Use upper case Roman numerals (I, II, III, IV) to distinguish ‘books’, arabic numerals (1, 2,

3) to denote chapters, and lower case Roman numerals (i, ii, iii, iv) to denote verses or clauses. In the first instance, the full reference to the translation (and, where applicable, edition) should follow the reference to book, chapter and verse. So, for example:

Gregory of Tours, Histories III.15. Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks , trans. L.

Thorpe (Harmondsworth, 1974); Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores Rerum

Merovingicarum I (part 1), ed. B. Krusch & W. Levison (Hannover, 1951).

Pactus Legis Salicae 24.ii. The Laws of the Salian Franks , trans. K. Fischer-Drew

(Philadelphia 1991).

In subsequent notes, these might be abbreviated to: Gregory, Histories , III.15; Pactus Legis

Salicae , 24.ii.

British Government Publications

Hansard Parliamentary Debates:

Parl. Debs. (series 4) vol. 24, col. 234 (24 March 1895)

Parliamentary Papers:

‘Title’.

Parliamentary Papers Year. [Document #], Volume #: page/s.

For example:

‘Report of the Jamaica Royal Commission Part I’. Parliamentary Papers 1866. [3683], 30:

39-41.

Subsequent: PP 1866 [3683], 30: 45.

‘Report of the Select Committee on the Extinction of Slavery Throughout the British

Dominions with the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index.’ Parliamentary Papers 1831-

32. [721], 20: 29.

19

Subsequent: PP 1831-32 [721], 20: 32.

Printed catalogues of governmental documents:

Calendar of Patent Rolls. Edward II, 1313-1317 (London, P.R.O., 1898), 614.

In subsequent notes, this might be abbreviated to C.P.R. Edw. II, 1313-17 , 614.

Manuscript Sources

These should give the location of the manuscript collection, followed by its title and reference number as well as a description of the document, its box/folio number and date. As with all references, the goal is to provide enough information to allow a reader to find the specific extract in the original. The following are suggestions; use common sense to develop clear references to the particular manuscript collections you are using.

Public Record Office, Kew, Foreign Office Records, FO 371/2388: Ambassador Greene to

Foreign Secretary Grey, 15 March 1915.

The British Library, Additional Manuscripts Collection, Ms. 49751: Note dictated by Arthur

Balfour 10 February 1919. Balfour Papers. Box 50, Folio 15.

Interviews

Tony Blair, personal interview with the author, 24 April 1997.

Films

In the Trenches , directed by Lionel Askins, with Joanna Bourke. Cityfilm, 1992.

Internet Sites

M.F. Maury, The Physical Geography of the Sea

(New York, 1855), [‘Making of America’ digital library] <http://moa.umdl.umich.edu/cgi/sgml/moa-idx?notsid=AFK9140>

The Harvard System

Distinct from the Oxford System, references are given within the main text in brackets. The reference comprises the author’s surname, date of publication and page number in the form:

(Caufield 2000: 22). When reference is made to two or more works, they are separated by a semi-colon (Musher 2001: 2; Caufield 2000: 54). If an author has published more than one work in a given year the works are distinguished by letters (Ross 1979a: 33; 1979b: 65).

In this system, the bibliography is formatted differently, with the author’s surname and initial followed immediately by the date of publication. The name of the publisher is also essential.

Thus the bibliography above would be written out as follows:

Caufield, S. (2000) In Defense of Honor: Sexual Morality, Modernity and Nation in Early-

Twentieth Century Brazil . London: Duke University Press.

Musher, S. (2001) ‘Contesting “the way the Almighty wants it”: Crafting memories of exslaves in the slave narrative collection’.

American Quarterly 53: 1-31.

Ross, R. (1979) ‘The Cape of Good Hope and the world economy, 1652-1835’ in R. Elphick and H. Giliomee (eds.). The Shaping of South African Society, 1652-1840 : 243-280.

Cape Town: Longman.

Fitting primary sources into the Harvard System style can be awkward and some style guides suggest that it is really only suitable for citing secondary sources. Consult your supervisor for advice on this.

20

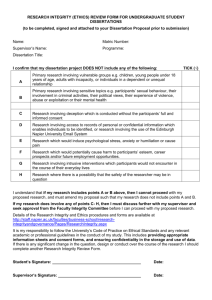

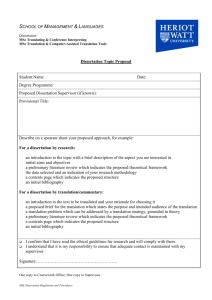

U NDERGRADUATE D ISSERTATION C OVER S HEET A

B EFORE SUBMITTING YOUR DISSERTATION , PLEASE CONFIRM THAT YOU HAVE READ THE

PLAGIARISM POLICY OF THE SCHOOL OF HISTORY

,

CLASSICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY

,

AS

DETAILED IN THE DISSERTATION GUIDELINES :

T ICK B OX :

□

P LEASE ALSO READ THE FOLLOWING EXTRACTS FROM THE EXAMINATION REGULATIONS

FOR BIRKBECK COLLEGE AND THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON :

14.7 Where the Regulations for any qualification provide for part of an examination to consist of ‘take-away’ papers, essays or other work written in a candidate’s own time, coursework assessment or any similar form of test the work submitted by the candidate must he his/her own and any quotation from the published or unpublished works of other persons must be duly acknowledged.

14.8 Failure to observe the above will constitute an examination offence . All examination offences will be treated as cheating or irregularities of a similar character under the

University of London Regulations for Proceedings in respect of Examination Irregularities.

Under these Regulations candidates found to have committed an offence may be excluded from all further examinations of the University and, or, of the College.

I confirm that I have read the above. I understand that any form of plagiarism is an infringement of College Examination Regulations and that all sources must be correctly acknowledged and referenced. I therefore declare that the attached dissertation, now being submitted, is my own work. I further agree to make available an electronic copy

(on floppy disk) of my dissertation, for testing by the JISC plagiarism detection service, if requested to do so.

S

IGNED

: ................................................................... D

ATE

...........................................................

N AME IN P RINTED C APITALS : .....................................................................................................

W ORD L ENGTH ....................................... C ANDIDATE N O . .........................................................

P LEASE CIRCLE AS APPLICABLE :

BA History BA History/Archaeology BA Classics BA Classical Studies

T ITLE OF D ISSERTATION : .............................................

...............................................................

...............................................................

21

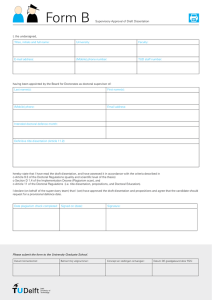

U NDERGRADUATE D ISSERTATION C OVER S HEET B

C ANDIDATE N O . ......................................

D ATE S UBMITTED ..............................

P

LEASE CIRCLE AS APPLICABLE

:

BA History BA History and Archaeology BA Classics BA Classical

Studies

T ITLE OF D ISSERTATION : ............................................................................................................

...............................................................

...............................................................

...............................................................

T HIS C OVER S HEET MUST OMIT YOUR NAME