Bovine trypanosomiasis in Nigeria

advertisement

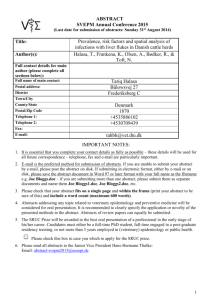

ISRAEL JOURNAL OF VETERINARY MEDICINE VOLUME 55 (2) 2000 EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT, SEASON, VEGETATION ZONE AND BREED ON THE PREVALENCE OF BOVINE TRYPANOSOMIASIS IN SOUTHWESTERN NIGERIA A. O. Ogunsanmi1, B. O. Ikede2 and S. O. Akpavie 2 1. Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Management. 2. Department of Veterinary Pathology, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria Summary Blood was examined to determine the prevalence of trypanosomiasis on 853 animals from 65 herds kept under modern and traditional management systems in the Ondo, Delta, Edo and Kwara States of Nigeria. The herds were located either in the rain forest or the derived savanna zones, which are the two ecological zones of Nigeria. A comparison of trypanosome infection rates in abattoir blood samples with those of resident herds in these zones was also carried out. The results indicated that sedentary management of cattle is associated with a reduced trypanosome infection rate as compared to the semi-sedentary type of management. The infection rates in sedentary and semi-sedentary herds were 9.8% and 42.8%, respectively, while the rates in the rain forest and derived savanna were 6.6% and 19.9%, respectively. The lower infection rates in the rain forest were attributed to increasing human activity in reducing the habitat for the vector. On the other hand, the high infection rate in the derived savanna was influenced by proximity to Glossina morsitans belt as well as to an increasing density of animals and grazing activities. The infection rate of the N’Dama was lower than those of Muturu, Keteku and Zebu breeds. The predominant species of trypanosomes trapped in this survey were Trypanosoma congolense and T. vivax, while Glossina palpalis and G. morsitans were the only trapped tsetse species. None of the tsetse was positive for trypanosomes. Introduction Some of the factors that affect the prevalence of trypanosomiasis in Nigeria include animal breed, type of management, season of the year and the type of vegetation. Ikeda et al. (1) observed that some riverine and forest species of tsetse fly are poorer vectors of trypanosomes than the savanna species. It is also known that nomadism tends to expose animals to high tsetse challenge and hence trypanosome infection. In Nigeria, cattle are considered as one of the principal livestock, and their survival and development are necessary to ameliorate the worsening situation regarding the supply of animal protein. Cattle production in the country has been restricted to the northern part (Table 1) because of the erroneous belief that the southern part (forest zone) was highly infected by tsetse flies which transmit trypanosomiasis (2). Table 1: Prevalence of bovine trypanosomiasis in Northern Nigeria (1952-1995). Study State (Location) # of Samples Positive Cases No. % Trypanosome species number of all infections T. T. congolense T. brucei vivax Ref Kwara Benue 10 298 8 80 6 2 0 3 109 36.6 10 79 20 4 Kwara 110 46 42 29 8 9 5 Kaduna 210 16 7.6 16 0 0 6 Plateau 206 20 9.7 11 4 5 7 Benue 268 24 9.0 9 8 7 8 In order to understand the current status of trypanosome infection in southern Nigeria, this study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of bovine trypanosomiasis in sedentary and semi-sedentary herds resident in the derived savanna and rain forest zones during the wet and dry seasons, to compare its prevalence among different breeds of cattle, and measure the trypanosome infection rate in abattoir blood samples and observe the tsetse population in the southwestern part of the country. Materials and Methods Animals A total of 853 animals from 65 herds of cattle situated in different parts of Ondo, Delta, Edo and Kwara States (southwestern Nigeria) were studied. Six hundred and sixty-six animals in sedentary herds and 187 animals in semi-sedentary herds were examined. Sixty-one herds were owned by traditional Fulari herdsmen who have settled in these areas for 3 to 10 years or more. The other four herds were modern herds, which belonged to Government or private owners. The breeds included Zebu, Muturu and N’Dama. The main preventive measure against the fly, in herds under intensive management (sedentary herds), were traps and screens (9). Due to the abundance of water and pasture during the rainy season, animals were usually kept away from streams and rivers to reduce tsetse contact. There were no preventive measures against the vector in extensively managed (semi-sedentary) herds. Abattoir blood samples Abattoir blood samples were obtained from four local Government abattoirs in Edo, Delta, Ondo and Kwara States. A total of 138 blood samples were collected from animals slaughtered at these abattoirs. Collection blood samples Animals were randomly selected from each herd as described by Putt et al. (10) and bled from the jugular vein using anti-coagulant EDTA vacutainer tubes. Abattoir blood samples were collected in universal bottles containing EDTA at slaughter from the severed jugular vein. All the samples were kept on ice and taken to the laboratory for examination. Packed cell volume and parasitaemia The packed cell volume (PCV%) was determined (11). Trypanosomes were detected and quantified in the blood samples by darkground/phase contrast buffy coat technique (DG) (12), and species of trypanosomes identified (13). Tsetse flies trapping, identification and examination Flies were caught by biconical trapping (9). Tsetse species were identified according to Murry et al. (13). Other biting flies were identified according to Davies (2). Statistics Data were statistically analyzed by Statistical Analysis System (14). Results The results of the trypanosome infection rates are shown in Tables 2 and 3. In the sedentary herds, 9.8% of the 666 animals were positive while 42.8% of the 187 animals in the semisedentary herds were positive. This difference is highly significant (p<0.001) (Table 2). The infection rate in the derived savanna zone was 19.8% and that of the rain forest zone, 6.6% (p<0.001) (Table 3). The results of the infection rates in the different breeds are presented in Table 4. The N’Dama had an infection rate of 2.0% while those of Muturu, Keteku and Zebu were 16.0%, 18.5% and 19.7%, respectively (p<0.05). Of all the animals examined, 17.0% were trypanosome positive, while T. congolense and T. vivax accounted for 10.6% and 7.6% of the infections, respectively (Table 2). Table 2: Managment system, trypanosome infection rates and tsetse catches in southwestern Nigeria. Positive No. of cases samples No. % Trypanosome species Glossina species T.congolense T.vivax G.palpalis G.Tachinoides Crysops Tab Biting flies Sedentary herds Dry season 364 42 11.5c 16 16 0 0 3 Wet season 302 23 7.6d 10 10 1 1 26 Sub total 666 65 9.8* 26 26 1 1 29 Dry season 42 12 8.6b 9 9 9 12 10 Wet season 145 68 46.9a 55 55 1 6 49 Semisedentary herds Sub total 187 80 42.8* Grand total 853 145 17.0 64 64 90 (10.6%) 65(7.6%) 10 18 59 11 19 88 Table 3: Ecological zones and trypanosome infection rates in southwestern Nigeria. Ecological No. of zones samples Positive cases No/ % Trypanosome species Glossina species Biting flies T. T. G. G. Crysops Tabanids Hippob congolense vivax palpalis tachnoides Derived savanna 672 133 19.8a 81 52 8 16 20 5 12 Rain forest 181 12 6.6b 10 2 3 3 68 18 20 Total 853 145 17.0 91 54 11 19 88 24 32 The packed cell volume (PCV) values are shown in Table 4. The N’Dama had a mean PCV of 30.2±1.9% while those negative for trypanosomes had a mean PCV of 33.0±2.3% (p>0.05). The infected Muturu had a mean PCV of 36.3±1.9% while those negative for trypanosome infection had a mean PCV of 37.1±2.4%. The trypanosome positive Keteku had a mean PCV value of 21.3±0.6% while the negative had a mean PCV of 24.5±1.0% (p<0.05). The positive Zebu had a mean PCV of 16.8±1.2% while the mean PCV for negative animals was 25.6±1.8% (p<0.05). None of the 138 abattoir blood samples was trypanosome positive. Table 4: Prevalence and mean PCV (%) of different breeds of trypanosomeinfected and non infected cattle in southwestern Nigeria. Breed DRY SEASON Positive cases WET SEASON Negative cases Positive Negative No. cases cases (No. Prevalence No. of of examined) Rate (%) samples PCV PCV cases PCV PCV No. No. No. No. (%) (%) (%) (%) N'DAMA (101) 2.0c 56 0 0 56 28.5+/1.8a 45 2 30.2+/33.0+/43 a 1.9 2.3a MUTURU (25) 16.0b 8 0 0 8 34.6+/2.2b 17 4 36.3+/37.1+/13 a 1.9 2.4a KETEKU (318) 18.5a 168 38 21.3+/24.5+/130 150 b 0.6 1.0a 17 25.3+/25.5+/133 a 0.4 2.2a ZEBU (426) 19.7a 191 17 16.8+/25.6+/174 235 c 1.2 1.8a 68 22.4+/26.6+/167 b 1.6 0.8a Thirty tsetse flies, 11 Glossina palpalis and 19 G. tachinoides, were caught, while 21 (70.0%) and 9 (30.0%) tsetse were trapped during the dry and wet seasons, respectively. In addition, 24 (80.0%) tsetse were trapped in the derived savanna zone and the other 6 (20.0%) were caught in the forest zone. None was positive for trypanosomes. Other biting flies caught were 88 Tabanus, 23 Chrysops and 320 Hippobosca species. Discussion The results of this study indicate that sedentary management of cattle is associated with a reduced trypanosome infection rate compared to semi-sedentary management. This observation agrees with that of MacLennan (15) who also observed that the innate resistance of cattle was increased by repeated exposure to the same population of trypanosomes in a given area. The semi-sedentary herds are continuously exposed to new strains of trypanosomes while other adverse husbandry stress factors predispose them to increased susceptibility and high infection rate. In the sedentary herds, the relatively high infection rate observed during the dry season might be due to higher animal and tsetse contact resulting from the concentration of the flies on riverbanks where there was green pasture and access to drinking water (15). The lower infection rate in the wet season may be as a result of the reduced animal and tsetse contact, abundance of pasture and water, coupled with reduced stress factors. The higher infection rate observed in the wet season in the semi-sedentary herds might be associated with a high tsetse risk at the cattle range. The cumulative effects of exposure to tsetse and new strains of trypanosomes in this season probably account for the observed infection rate (15). The results of this study indicated differences in trypanosome infection rates in the different ecological zones. The low infection rate in the rain forest zone is likely to be due to increasing human activity in this zone and the presence of few effective vectors. The high trypanosome infection rate in the derived savanna zone could be linked to its proximity to the morasitans belt. The resistance of the N’Dama to trypanosome infection was superior to that of Muturu, Keteku and Zebu breeds. The trypanotolerance of the N’Dama is well known (16, 17). The relative resistance of Muturu and Keteku has also been reported (18, 19, 20). The predominant species of trypanosomes encountered were T. congolense and T. vivax. Davies (2) attributed the predominance of T. congolense to the fact that drugs used in Nigeria are better at curing T. vivax infections than those of T. congolense. Single infections of T. congolense or T. vivax were encountered more frequently than mixed infections. The PCV is the most reliable indicator of anaemia in trypanosomiasis (21,22). In this study, there were no significant differences between the PCVs of infected and non-infected N’Dama and Muturu during the wet season. The reason might be partly due to the high nutritional status and their relative trypanotolerance. The low PCV values of the Keteku and Zebu is in agreement with previous findings (23, 24) who reported that trypanosomiasis caused depressed PCV levels in infected animals. All four breeds, infected or not, had slightly higher PCV values in the wet season than in the dry season. This may again be related to seasonal nutritional variations. Glossina palpalis and G. tachinoides were the most widely distributed species of tsetse flies in the area studied. None of the dissected tsetse was positive for trypanosomes. The low infection rates of tsetse could explain the low prevalence of trypanosomiasis observed in the study area, especially in the rain forest zone. The study revealed that fewer tsetse were caught compared to the number of biting flies which act as mechanical transmitters of trypanosomes while the epidemiology of animal trypanosomiasis has not been clearly defined (25, 26). The absence of trypanosomes in the abattoir blood samples examined in this study could be due to the faster and modern mode of transportation of trade cattle from the northern to the southern cattle markets (27). This has helped to reduce the incidence of tsetse and cattle contact as well as reduce the stressful effect of trekking, both of which normally result in higher trypanosome infection rates. In conclusion, the findings of this study and of previous workers (1, 28) have shown that trypanosomiasis may not be serious limiting factor to livestock production in sedentary cattle herds. We are therefore of the opinion that an intensive commercial production of Zebu breeds coupled with good management could be encouraged in southern Nigeria. References 1. Ikeda, B.O., Reynolds, L., Ogunsanmi, A.O., Fawunmi, M.K., Ekwuruke, J.O. and Taiwo, V.O.: The epizootiology of bovine trypanosomiasis in the derived savanna zone of Nigeria. A preliminary report. Proceedings of the 19th Meeting of the ISCTRC/OAU, Loma, pp 1-6, 1986. 2. Davies, H.: Tsetse flies in Nigeria. Oxford University Press, Ibadan, pp. 1-86, 1977. 3. Unsworth, K. and Birkett, J.: The use of antrycide prosalt in protecting cattle against trypanosomiasis when in transit through tsetse areas. Vet. Rec. 64: 351-353, 1952. 4. Godfrey, D.G. and Killick-Kendrick, R.: Bovine trypanosomiasis in Nigeria. I. The inoculation of blood into rats as methods of survey in Dinga Valley, Benue Province. Ann Trop. Med. Parasitol. 55: 287-297, 1961. 5. Godfrey, D.G., Killick-Kendrick, R. and Ferguson, W.: Bovine trypanosomiasis in Nigeria. IV. Observations on cattle trekked along trade route through areas infested with tsetse fly. Ann Trop. Med. Parasitol. 59: 255-269, 1965. 6. Agu, W.E.: Incidence of bovine trypanosomiasis in six villages of Kaduna State, Nigeria. National Conference on Disease of Ruminants, Vom, Nigeria, 3-6 October 1984. 7. Joshua, R. A.: The prevalence of trypanosomiasis in cattle at low-lying zone of the Jos Plateau, Nigeria. Bull. Anim. Hlth. Prod. Afr. 34: 71-72, 1986. 8. Kalu, A.U.: Prevalence of trypanosomiasis among trypanotolerant cattle in the lower Benue River area of Nigeria. Prev. Vet. Med. 24(2): 97-103, 1995. 9. Challier, A. and Laveissiere, C.: A new trap for capturing Glossina (Diptera, Muscidae): Description and field trials. Cah. ORSTOM, Ser. Entomol. Med. Parasitol. 11: 251-262, 1973. 10. Putt, S.N.H., Shaw, A.P.N. Woods, A.J. and James, A.D.: Veterinary epidemiology and economics in Africa. A manual for use in the design and appraisal of livestock health policy. ILCA, Addis Ababa, pp. 27-66, 1987. 11. Jain, N.C.: Schalms Veterinary Haematology, 4th ed., Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, pp. 1-86, 1986. 12. Paris, J., Murray, M. and MacOdimba, F.: A comparative evaluation of the parasitological techniques currently available for African trypanosomiasis in cattle. Acta Tropica (Basel), 39: 307-316, 1982. 13. Murray, M., Trail, J.C.M., Turner, D.A. and Wissocq, Y.: Livestock productivity and trypanotolerance. Network training manual. ILCA, Addis Ababa, pp. 45-75, 1983. 14. SAS Institute Inc.: SAS User’s Guide, Version 5, Cary, NC, USA, 1985. 15. MacLennan, K.J.R.: Tsetse-transmitted trypanosomiasis in relation to rural economy in Africa. Part I. Tsetse infestation. FAO Anim. Prod. Hlth. 37: 48-63, 1983. 16. Chandler, R.L.: Comparative tolerance of West African N’Dama cattle to trypanosomiasis. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 46: 127-134, 1952. 17. Desowitz, R.S.: Studies on the immunity and host-parasite relationship. I. The immunological response of resistant and susceptible breeds of cattle to trypanosomal challenge. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 53: 293-313, 1959. 18. Stewart, J.L.: The West African Shorthorn cattle. Their value to Africa as trypanosomiasis-resistant animals. Vet. Rec. 63: 454-457, 1951. 19. Roberts, C.J. and Gray, A. R.: Studies on trypanosome resistant cattle. II. The effect of trypanosomiasis on N’Dama, Muturu and Zebu cattle. Trop. Anim. Hlth. Prod. 5: 220-233, 1973. 20. ILCA: Trypanotolerant Livestock in West and Central Africa. Vol. 2. Country Studies, ILCA, Addis Ababa, 1979. 21. Murray, M.: Anaemia of bovine trypanosomiasis. In: Losos, G.J. and Chouinard, A. (Eds.): Pathogenicity of Trypanosomes. No. 132e. IDRC, Ottawa, pp.121-127, 1978. 22. Morrison, W.I., Murray, M. and McIntyre, W.I.M.: Bovine trypanosomiasis. In: Ristic, M. and McIntyre, I. (Eds.): Diseases of cattle in the tropics. Economic and zoonotic relevance. Vol. 6, Martinus Nyhoff Publishers, The Hague/Boston/London, pp. 486-488, 1981. 23. Losos, G.J. and Ikeda, B.O.: Review of the disease in domestic and laboratory animals caused by Trypanosoma congolense, T. vivax, T. brucei, T. rhodesiense and T. gambiense. Vet. Pathol. 9 (Suppl.): 1-17, 1972. 24. Anosa, V.O. and Obi, T.U.: Haematological studies on domestic animals in Nigeria. III the effects of age, breed and haemoglobin type on bovine haematology and anaemia. Zbl. Vet. Med. 27: 773-788, 1980. 25. Kalu, A.U. and Uzoigwe, N.R.: Tsetse fly and animal trypanosomiasis in Jos Plateau: Observations on outbreaks in Barkin-Ladi Local Govern