trypanosomoses_1_introduction

advertisement

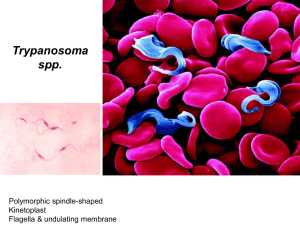

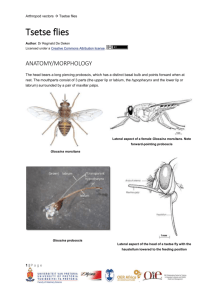

Trypanosomoses Author: Vincent Delespaux Adapted from: R.J. CONNOR and P. VAN DEN BOSSCHE, 2004, African animal trypanosomoses, in Infectious diseases of livestock, edited by J.A.W. Coetzer & R.C. Tustin. Oxford University Press, Cape Town, 12: 251 – 295 Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution license. INTRODUCTION The trypanosomoses are diseases of humans and domestic animals that result from infection with parasitic protozoa of the genus Trypanosoma. Trypanosomes parasitize all classes of vertebrates: fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. The parasites, with the exception of Trypanosoma equiperdum, the cause of dourine, are transmitted from host to host by haematophagous vectors, and usually cause little appreciable harm to either the vector or the vertebrate host. However, several species of trypanosomes which parasitize mammals are less well adapted and commonly cause disease. Trypanosomosis is generally characterized by the intermittent presence of parasites in the blood and intermittent fever. Anaemia usually develops in affected animals, and this is followed by loss of body condition, reduced productivity and, often, high mortality. The first report that associated trypanosomes with disease was made from India in 1880. In 1895 a major discovery was made in Zululand, South Africa that trypanosomes were the causal organisms of ‘nagana’, or tsetse fly disease. Two forms of human trypanosomosis exist: Chagas' disease occurs in Central and South America and is transmitted by bloodsucking reduviid bugs, certain small wild animals and dogs harbouring the infection. The second form is human sleeping sickness. This occurs in Africa and is transmitted by bloodsucking flies of the genus Glossina, commonly known as ‘tsetse flies’ or simply as ‘tsetse’. The majority of animal diseases caused by trypanosomes occur in the tropics. In Africa, several species of tsetse-transmitted trypanosomes cause African trypanosomoses in domestic animals, which in southern Africa are collectively known as ‘nagana’, a word derived from the Zulu word ‘nakane’ meaning tsetse fly disease. ‘Surra’ is transmitted by biting flies other than tsetse flies and, although it occurs in many parts of the tropics, including northern Africa, it is not present in southern Africa. The large populations of wild animals, which have thrived for millennia in the tsetse-infested tracts of Africa have evolved with these flies and the trypanosomes they transmit. Hosts and parasites have become mutually adapted and co-exist in a balanced relationship. Humans first brought domestic animals into the tsetse belts of Africa relatively recently. Because of this recent introduction, the relationship 1|Page between tsetse-transmitted trypanosomes and domestic animals has not fully evolved and infection with these parasites frequently produces disease. The devastation which resulted from the rinderpest pandemic of the 1890s destroyed almost entire populations of wild animals and millions of cattle. Without hosts on which to feed, tsetse disappeared from large areas. However, a few decades later, tsetse were dispersing from residual pockets, and trypanosomosis again became a problem for livestock owners. By 1931, tsetse were spreading at a rate of 2500 square kilometres (1000 square miles) annually, and game elimination to control tsetse began in 1932. Since then strenuous efforts have been made to contain the tsetse fly. In many other parts of southern Africa, livestock owners have also had to live with the tsetse fly and its consequences. Tsetse infest 10 million square kilometres and affect 37 countries, which makes African animal trypanosomosis a problem of truly continental magnitude. They live in frost-free areas that have an annual rainfall of 650 mm or more. In arid, marginal habitats, tsetse only exist in the better wooded and better watered strips where the host species concentrate during critical times, such as in the late, hot, dry season. Most of the settled areas of the tsetse fly belts of southern Africa are used for traditional mixed farming, but the presence of tsetse seriously handicaps development. Tsetse fly Cattle Trypanotolerant cattle General distribution of tsetse flies and cattle in Africa 2|Page Concerted efforts to control tsetse over the past 50 years have resulted in significant changes in the distribution of tsetse and tsetse-transmitted trypanosomosis. Unfortunately, few of these achievements have been sustained. In many countries of southern Africa, the current distribution of tsetse and, hence, tsetse-transmitted trypanosomosis is not much different from the ecological limits of the fly distribution. Early work on trypanosomosis, much of it conducted in southern Africa, concentrated on describing the trypanosomes and studying the natural history of the parasites, their vectors and their hosts. The greatest advances in knowledge of trypanosomosis over the past two decades have been made in the areas of molecular biology and immunology. 3|Page