msTARAS

advertisement

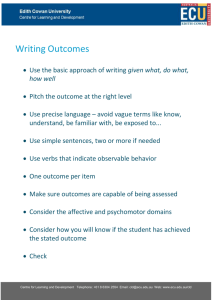

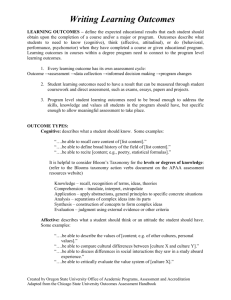

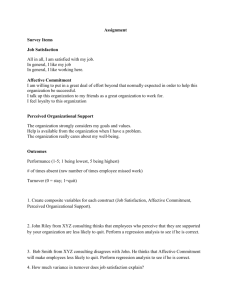

Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations Theory of Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations (TARAS): A Cognitive Account of Negativity Dominance Ulrich Schimmack University of Toronto, Mississauga Stan Colcombe University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign February 2002 RUNNING HEAD: Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations about 6,000 words Ulrich Schimmack Department of Psychology University of Toronto at Mississauga Erindale College 3359 Mississauga Road North Mississauga, Ontario, L5L 1C6 Canada email: uli.schimmack@utoronto.ca 1 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations Abstract Negativity dominance in affective reactions to conflicting picture pairs was examined (Rozin & Royzman, 2001). Negativity dominance assumes that a pair of a positive and a negative picture elicits more displeasure and/or less pleasure than the positive and the negative picture in isolation. The type of positive (erotic vs. non-erotic) and negative (moderate vs. strong) pictures was manipulated. Negativity dominance was expected to be stronger for pairs with strong negative pictures and weaker for pairs with erotic positive pictures. We also predicted that conflicting pairs with an erotic positive picture elicit more intense mixed feelings (pleasure & displeasure) than conflicting picture pairs with a non-erotic positive picture. All three hypotheses were supported. 2 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 3 Theory of Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations (TARAS): A Cognitive Account of Negativity Dominance Experiences of pleasure and displeasure are a prominent topic in psychology (Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988; Rozin, 1999; Schimmack, 2001). Several emotion theories consider pleasure and displeasure core elements of affective experiences (Ortony et al., 1988; Reisenzein, 1992; Schimmack, Oishi, Diener, & Suh, 2000; Weiner, 1986; Wierzbicka, 1992). Furthermore, well-being researchers rely on pleasure and displeasure as important indicators of subjective well-being or happiness (Diener, 1984; Kahneman, 1999; Schimmack, Diener, & Oishi, 2001; Schimmack, Radhakrishnan, Oishi, Dzokoto, & Ahadi, in press). Kahneman, Diener, and Schwarz (1999) even proposed hedonic psychology as a field entirely devoted to the "study of what makes experiences and life pleasant and unpleasant" (p. xi). Appraisals as Determinants of Pleasure and Displeasure The determinants of pleasure and displeasure have been studied extensively by appraisal theorists of emotions (e.g., Lazarus, 1991; Ortony et al., 1988; Reisenzein & Spielhofer, 1994; Scherer, 1984, 2001; Smith & Kirby, 2000, 2001). Accord to appraisal theories, pleasure and displeasure are outcomes of appraisals of the environment with regard to one's own needs, goals, desires, or standards. Favorable comparisons produce pleasure, whereas unfavorable comparisons produce displeasure. Ortony et al. (1988) differentiate three classes of appraisals, namely (a) appraisals of event-outcomes, (b) appraisals of agents' actions, and (c) appraisals of objects. The present article is concerned with appraisals of objects. According to Ortony et al. (1988), objects are appraised in terms of appealingness. Appealing objects elicit pleasure, whereas appalling objects elicit displeasure. However, what emotional response is elicited by conflicting appraisals? For example, you may walk along a tropical beach littered with trash. The white sand and Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 4 blue water is appraised as appealing, whereas the trash is appraised as appalling. What is the affective experience in this situation? Theory of Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations (TARAS) Schimmack (2002) proposed the Distributed Attention Theory of Emotions (DATE) to explain affective reactions to conflicting situations. However, Kappas (2001) used the acronym DATE for his Dynamic Appraisal Theory of Emotion. Hence, we changed the name of our theory to Theory of Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations (TARAS). TARAS was inspired by existing appraisal theories (Reisenzein, 2001; Scherer, 2001; Smith & Kirby, 2001) and it is in general agreement with other appraisal theories. The major difference to other appraisal theories is that TARAS is explicitly a theory of affective reactions to conflicting situations, whereas other appraisal theories typically focus on affective responses to a single event or a single aspect of a complex event. The main assumption of TARAS is that affective reactions to conflicting situations depend on the focus of attention (cf. Ortony et al., 1988; Scherer, 2001). In real life, people are constantly confronted with multiple objects. To function in these complex situations, people need to select the most relevant objects for more elaborate processing. Scherer (2001) postulated that the first step of an appraisal process is the deployment of attention to the most relevant aspects of a complex situation for more detailed appraisals of these aspects. Hence, affective reactions to conflicting situations should depend primarily on the appraisal of a few aspects in the focus of attention. The same assumption is made in Ortony et al.’s (1988) discussion of conflicting situations, such as a friend getting an undeserved pay raise. This event can be appraised from the perspective of something good happening to a friend (positive) and from a perspective of fairness (negative). Ortony et al. (1988) assume that the affective reaction to the event depends on the focus of attention. If attention is devoted to fairness, the event elicits displeasure. If attention is focused on the friend’s fortune, the event elicits pleasure. However, the authors also assume that it is possible to attend to both aspects of Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 5 the situation and to make conflicting appraisals. “It is entirely possible for a person to take both perspectives and to have ’mixed feelings’ about such an event” (p. 102). In short, TARAS assumes that affective reactions to conflicting situations are influenced by attention processes. If attention focused entirely on the positive aspect of a situation, people should experience only pleasure and no displeasure. If attention focused only on the negative aspect of a situation, then people should experience only displeasure and no pleasure. If attention focused on both the positive and the negative aspect, the experience would be mixed – pleasant and unpleasant. However, the amount of pleasure and displeasure should depend on the distribution of attention. The more attention focuses on the negative aspect, the less attention is devoted to other stimuli (cf. MacLin, MacLin, & Malpass, 2001). Hence, attentional biases toward the negative pictures should increase displeasure and decrease pleasure. TARAS’s Explanation of Negativity Dominance Rozin and Royzman (2001) noted that affective reactions to conflicting situations often produce negativity dominance. That is, the affective response to trash on a beach is more negative (less pleasant and/or more unpleasant) than the algebraic sum of the pleasure elicited by the beach without trash and the displeasure elicited by trash without a beach. Rozin and Royzman’s (2001) review revealed only a few studies that documented negativity dominance because affective reactions to conflicting situations have been neglected in contemporary affect research. Furthermore, the processes underlying negativity dominance are largely unknown. We propose that TARAS can explain negativity dominance in people’s affective reactions to conflicting situations. The reason is that negative stimuli often attract more attention than positive stimuli (Pratto & John, 1991; see Rozin & Royzman, 2001, for a review). Recently, Mogg, McNamara, Powys, Rawlinson, Seiffer, and Bradley (2000) tested the influence of concurrent presentations of positive and negative pictures on attention. Participants saw pairs of appealing and appalling pictures. After 500 ms, a dot Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 6 appeared in the location of one of the two pictures and participants had to press a button as soon as they detected the dot. Participants were faster in detecting the dot in the location of a negative picture than in the location of a positive picture, and this effect was more pronounced for strong negative pictures than for moderate negative pictures. This study suggests that in conflicting situations with a positive picture and a negative picture, the negative picture attracts more attention. If the picture that attracts more attention has a stronger impact on the affective reaction, then conflicting picture-pairs should produce negativity dominance. In short, we propose that affective reactions to conflicting situations depend on the distribution of attention. Typically, the appalling aspect of the situation attracts more attention, which produces negativity dominance in the affective reactions. One major implication of the cognitive theory of negativity dominance is that positive stimuli that attract attention should reduce negativity dominance. Influence of Different Types of Appealing Pictures on Attention Several lines of research suggest that positive stimuli can vary in their ability to attract attention independent of their appealingness. In particular, erotic stimuli have been shown to attract more attention than other appealing stimuli. For example, Pratto (1994) demonstrated that the negativity bias in attention disappeared when negative words were pitted against erotic words in the Emotional Stroop task. Research with affective pictures also attests to the attention-grabbing quality of erotic material (Bradley Codispoti, Cuthbert, & Lang, 2001; Lang, Greenwald, Bradley & Hamm, 1993). These studies show that erotic stimuli elicit the same amount of pleasure as many other appealing pictures but differ from other appealing stimuli in variables related to attention. Namely, erotic pictures elicit higher arousal ratings, more skin conductance responses, higher interest ratings, and longer viewing times than non-erotic positive pictures. Hence, we decided to manipulate the type of positive pictures to provide a first test of our cognitive theory of negativity dominance. We predicted that affective reactions to Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 7 conflicting picture-pairs produce negativity dominance when the positive picture does not attract attention (i.e., highly pleasant, non-erotic pictures). However, negativity dominance should be weaker for conflicting pairs that include attention-grabbing positive pictures (i.e., erotic pictures). We also manipulated the strength of negative pictures. Mogg et al. (2000) demonstrated that strong negative pictures attract more attention than moderate negative pictures. Hence, we predicted that conflicting pairs with strong negative pictures produce stronger negativity dominance than conflicting pairs with moderate negative pictures. This prediction is independent of the strength of the affective reaction to moderate and strong negative pictures because the test of negativity dominance controls for this difference (see Results section). Mixed Feelings We also examined whether conflicting picture pairs elicit mixed feelings (cf. Schimmack, 2001). Ortony et al. (1988) hypothesized that people experience mixed feelings when they appraise both the positive and the negative aspect of a situation. Similarly, TARAS allows for mixed feelings if people divide their attention between positive and negative aspects of the situation. However, the negativity bias in attention suggests that people are more likely to focus on the negative aspect of a situation, which would reduce the experience of pleasure and therewith the experience of mixed feelings. As a result, the experience of mixed feelings should depend the ability of positive pictures to attract attention. Conflicting pairs with non-erotic positive pictures that do not attract attention should produce less mixed feelings than conflicting pairs with erotic pictures that do attract attention. Predictions We examined affective reactions to conflicting picture-pairs, and we manipulated the type of positive and negative pictures in these pairs. We made the following predictions: Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations (a) Conflicting pairs with a strong negative picture produce stronger negativity dominance than pairs with a moderate negative picture. (b) Conflicting pairs with an erotic picture produce weaker negativity dominance than pairs with a non-erotic positive picture. (c) Conflicting pairs with an erotic picture elicit stronger mixed feelings than conflicting pairs with a non-erotic positive picture. Method Participants Eighty male students at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, took part in the study for course credit. Another 26 students from the same population participated in a pilot study that examined the validity of our stimulus selection. We chose male participants because men respond more strongly to erotic pictorial material (Bradley, Codispoti, Sabatinelli, & Lang, 2001) and because it was easier to obtain erotic pictures depicting female models than male models. Materials Pictures were taken partly from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1995), and partly from free Internet sites. All pictures were edited to be 300 pixels wide and 450 pixels long to enable side-by-side presentations on an 800 x 600 pixel screen. Furthermore, we used black-and-white pictures because the computers for this study did not support high quality color presentations. We compiled a set of 50 pictures that included 10 non-erotic positive pictures (NEP), 10 erotic positive pictures (EP), 10 moderate negative pictures (MN) and 10 strong negative pictures (SN). We also created 10 “neutral” pictures, which were white frames that were filled with the background color of the screen. We used these stimuli to measure affective reactions to the affective pictures in a neutral context, while still presenting two frames on all trials (recent work shows that the same results are obtained with truly neutral pictures; e.g., a hairdryer). Affective reactions to the pictures in 8 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 9 isolation (or in a neutral context) are essential for testing negativity dominance (see Results section). In a pilot study, 26 students saw each of the 50 pictures for 4s in a randomized sequence. After each picture, students rated how pleasant, unpleasant, excited, and tense they felt during the picture presentation. Ratings were made on a seven-point scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 6 = extremely. The most important finding of the pilot study was that non-erotic positive pictures (M = 3.40) elicited as much pleasure as erotic pleasant pictures (M = 3.68), t(25) = 1.24, p = .23. However, erotic pictures elicited more excitement (M = 3.56) than the non-erotic positive pictures (M = 1.65). This finding is consistent with previous studies that erotic pictures can be more arousing and attentiongrabbing, while eliciting as much pleasure as non-erotic pictures (Bradley et al., 2001; Lang et al., 1993). However, amount of displeasure is highly correlated with arousal (Lang et al., 1993). This correlation was confirmed in our pilot study. Strong negative pictures elicited more displeasure and more tension (Ms = 3.99, 2.86, respectively) than moderate negative pictures (Ms = 2.93, 1.83), t(25) > 3.00. Procedure The 50 pictures were presented in 25 pairs. The pairs were based on a complete pairing of the five stimulus types. The computer randomly determined the assignment of the 10 pictures of each stimulus type to the 25 pairs. For example, the non-erotic positive picture of a puppy was paired with a neutral, erotic-positive, moderate-negative, and a strong-negative picture for different participants. The random assignment of individual pictures to pairs controlled for unique context effects of particular combinations of pictures and the variation within the five sets of pictures. The computer also randomly determined the presentation order of the 25 pairs. We used two presentation modes. Forty-four participants saw the two pictures of each pair in rapid (400 ms) alternation. The remaining 36 participants saw the two pictures of each pair side by side. Each presentation lasted 4s. Afterwards, the pictures were removed and Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 10 a rating scale appeared. Participants rated the intensity of pleasure, displeasure on a seven-point intensity scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 6 = extremely intense. The computer randomly determined the order of the items. Results To test significance, we used two-tailed tests and an alpha error of .05. Our design implied that pairs of two different picture types were presented twice. For side-by-side presentations, we examined whether the arrangement of stimuli had an effect. However, we found no difference between pairs with a positive picture on the left and a negative picture on the right side and pairs with the reverse arrangement. Thus, we averaged the data across the two replications of these pairs. Next, we explored whether the presentation mode, side-by-side versus rapid alternation, influenced the results. Again, no significant differences were found. Pleasure To examine pleasure in conflicting pairs we computed a 2 x 3 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with type of positive picture (erotic vs. non-erotic) and type of context picture (neutral, moderate negative, strong negative) as within-subject variables. We predicted that the negative pictures reduce pleasure, and that the reduction is stronger for non-erotic pictures than for erotic pictures. This prediction was supported by a significant interaction, F(2, 158) = 114.26. Figure 1 shows the pattern of the interaction. The presence of a negative picture decreased the pleasure that the positive picture elicited in a neutral context. Strong negative pictures had a stronger impact than moderate negative pictures. This effect is consistent with Mogg et al.’s (2000) finding that strong negative pictures attract more attention than moderate negative pictures. The most important finding is that erotic pictures were less influenced by the presence of a negative picture than non-erotic picture. The differences in pleasure between erotic pictures and non-erotic pictures in the context of negative pictures were significantly larger than the difference in the neutral context. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 11 Displeasure We conducted the same type of analysis for displeasure. That is, we computed a 2 x 3 Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with type of negative picture (moderate vs. strong) and type of context picture (neutral, non-erotic, erotic) as within-subject variables. Again, we obtained a significant interaction, F(2, 158) = F(2, 158) = 78.60. Figure 2 shows the pattern of the interaction. Strong negative pictures elicit more displeasure than moderate negative pictures in all contexts. The presence of a positive picture decreases the full amount of displeasure that negative pictures elicited in the neutral context. The suppression of displeasure was stronger for erotic pictures than for non-erotic pictures. The interaction is due to the fact that erotic pictures produced the same suppression effect for moderate and strong negative pictures, whereas non-erotic pictures has a weaker suppression effect on strong negative pictures than on moderate negative pictures. Negativity Dominance The next analysis directly tested negativity dominance. Negativity dominance can be tested by determining the effect of pairing pictures with an opposing picture on pleasure and displeasure. First, we determined the difference in pleasure (D[P]) by subtracting pleasure in response to a conflicting pair (CP) from pleasure elicited by the positive picture in a neutral (N) context (D[P] = PN – PCP). Then we determined the difference in displeasure (D[D]) by subtracting displeasure in response to a conflicting pair (CP) from displeasure elicited by the negative picture in a neutral (N) context (D[D] = DN – DCP). Then we subtracted P[D] from D[D] to create a combination index (CI). The CI is constructed so that negative values reflect negativity dominance. For example, assume that a positive picture elicits strong pleasure (4) and a negative picture elicits strong displeasure (4) and the combination of both pictures elicits mild pleasure (1) and moderate displeasure (3). In this case, the difference in pleasure would be larger (D[P] = 4 – 1 = 3) than the difference in displeasure (D[D] = 4 – 3 = 1) and the combination index would be negative (CI = 1 – 3 = -2). Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 12 We computed CI values for the four types of conflicting pairs and submitted these values to a 2 x 2 ANOVA with type of positive picture (erotic vs. non-erotic) and type of negative picture (moderate vs. strong) as within-subject variables. The ANOVA revealed significant main effects for type of positive picture, F(1,79) = 31.45, and type of negative picture, F(1,79) = 12.96. The interaction failed to reach significance, F(1,79) = 3.44, p = .07. Figure 3 shows the pattern of results. The most important finding was the main effect for type of positive picture: As predicted, conflicting pairs with non-erotic pictures revealed negativity dominance, whereas negativity dominance was weaker for erotic pictures. In fact, erotic pictures were able to fully eliminate the typical negativity dominance effect when paired with strong negative pictures and there was a trend (p = .06) towards positivity dominance for pairs of erotic pictures and moderate negative pictures. The main effect for type of negative pictures shows a stronger negativity dominance effect for strong negative pictures. This finding is also consistent with our predictions. Mixed Feelings The final analyses examined the occurrence of mixed feelings in response to conflicting picture pairs. The intensity of mixed feelings was derived from participants’ pleasure and displeasure ratings, using the MIN statistic (Schimmack, 2001). MIN resumes the lower values of the two ratings. If pleasure or displeasure were zero, MIN resumes a value of zero, which reflects that at least one of the two affects was absent (i.e., intensity = 0). Hence, MIN values of zero indicate that pleasure and displeasure did not co-occur. Averaged across many trials, MIN values close to zero indicate that pleasure and displeasure are mutually exclusive. In contrast, MIN values greater than zero indicate that participants experienced pleasure and displeasure during the picture presentation. We used MIN values in response to the “neutral pair” (i.e., two empty frames) to control for the influences of response styles. MIN for neutral pairs was close to zero (M = 0.19), indicating that response styles had a negligible influence on the affect ratings. This Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 13 finding is consistent with other findings that response styles in affect ratings are negligible (Schimmack, Bockenholt, & Reisenzein, in press; Watson & Clark, 1997). MIN values for the four types of conflicting pairs were all significantly higher than those the MIN value for the neutral pair, t(79) > 5.00. We computed an ANOVA with type of positive picture (non-erotic vs. erotic) and type of negative picture (moderate vs. strong) as within-subject variables and MIN scores as the dependent variable. The main effect for type of positive picture was significant, F(1,79) = 16.73. The main effect for type of negative picture failed to be significant, F(1,79) < 3.39, p = .07. The interaction was not significant, F = 2.16, p = .16. Figure 4 shows the pattern of the data. As predicted, conflicting pairs with an erotic picture elicited stronger mixed feelings than conflicting pairs with a non-erotic positive picture. Although the overall interaction was not significant, a direct comparison suggested that pairs of an erotic picture and a strong negative picture elicited stronger mixed feelings than pairs of an erotic picture and a moderate negative picture, t(79) = 2.14. Discussion We examined affective reactions to conflicting picture pairs. The results of our study supported our hypotheses. Affective reactions to conflicting situations typically show negativity dominance (Rozin & Royzman, 2001). However, the magnitude of this effect depended on the nature of the positive and the negative picture. Most important, negativity dominance was eliminated for conflicting pairs with erotic pictures as positive stimulus. This finding is consistent with our cognitive theory of affective reactions to conflicting situations (TARAS). TARAS predicts that erotic pictures reduce negativity dominance because they attract more attention. We also found that strong negative pictures produced stronger negativity dominance than moderate negative pictures. This finding is also consistent with our cognitive theory of negativity dominance because strong negative pictures attract more attention than moderate negative pictures (Mogg et al., 2001). Finally, we found that conflicting pairs with an erotic picture elicited more Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 14 intense mixed feelings than conflicting pairs with a non-erotic positive picture. Once more, this finding is consistent with our cognitive theory. Accordingly, the experience of mixed feelings depends on the focus of attention. Mixed feelings should only be experienced if people attend to both the positive and the negative aspect of a situation. For conflicting pairs with non-erotic pictures attention is heavily biased towards the negative picture, which drastically reduces pleasure. In contrast, erotic pictures attract more attention, which maintains higher levels of pleasure besides the experience of displeasure, resulting in more intense mixed feelings. Alternative Explanations We did not manipulate attention directly. Hence, it is possible that our findings can be explained by alternative variables. One explanation would be the extremity of the affective response. Strong negative pictures could produce stronger negativity dominance because they produce stronger activity in neurological substrates that suppress the generation of pleasure. However, this alternative explanation cannot account for the effect of erotic pictures on negativity dominance because non-erotic and erotic positive pictures elicited the same amount of pleasure. Another alternative explanation could be that nonerotic pictures and erotic pictures elicit two different types of pleasure (e.g., relaxation, sexual excitement). Maybe sexual excitement is more resistant to concurrent negative stimuli than relaxation. However, this alternative explanation cannot explain the stronger negativity dominance for strong negative pictures to moderate negative pictures because these pictures did not elicit qualitatively different feelings. It is more difficult to dismiss general arousal as an explanation because both erotic pictures and strong negative pictures are more arousing than non-erotic and moderate negative pictures. Nevertheless, general arousal cannot explain the data pattern. If we assume a general arousal dimension, then a pair of an erotic positive picture (high arousal) and a moderate negative picture (low arousal) would produce a similar amount of arousal than a non-erotic positive picture (low arousal) and a strong negative picture (high Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 15 arousal). However, these two conditions have very different affective outcomes. The former condition yields slight positive dominance and the latter condition yields strong negativity dominance. In short, our cognitive explanation of negativity dominance provides a parsimonious and plausible account of the data pattern. Future research needs to test the influence of direct manipulation of attention on negativity dominance. Ecological Validity Our experimental paradigm had the advantage of providing a direct test of negativity dominance, which requires the assessment of the algebraic sum of affective reactions to the aspects of a conflicting stimulus in isolation (Rozin & Royzman, 2001). The cost of this advantage is that our paradigm has no direct equivalent in the real world. The trade-off between ecological validity and internal validity is of course not unique to our paradigm but common to many other influential paradigms in emotion research (e.g., emotional Stroop task, dot-probe paradigm, affective priming tasks, etc.). Nevertheless, we believe that our results are important for the understanding of emotions in the real world. First, it is entirely possible that two unrelated stimuli are appraised at the same time. The two stimuli can be an internal sensation and an external stimulus (e.g., watching an interesting movie with a full bladder) or two external stimuli (e.g., watching the waves while hearing the noise of a busy highway). It seems plausible that humans’ affective reactions to two conflicting and unrelated stimuli in the real world would also be influenced by the focus of attention. Another open question is the generalizability of our findings to affective reactions to a single object with conflicting attributes (e.g., a property with a fabulous view on a busy street). Although affective reactions to two unrelated objects seem to be different from affective reactions to one object with two conflicting attributes, this distinction may be more logical than psychological. Ortony et al. (1988) noted that the same situation could be described in alternative ways. For example, imagine a house buyer who is seeing a house for sale, which looks very appealing but which is located at a busy intersection. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 16 Does the house buyer have an affective reaction to a single object (the property as a whole) or an affective reaction to the two salient aspects of the property (the beauty of the house, the noisy intersection)? Furthermore, does the classification of this situation as a response to a single object or as one to two unrelated objects make any difference for the prediction of the affective reaction? We believe that our findings can be plausibly applied to this common everyday example. Just assume that the buyer is blind or deaf. We would predict that the blind buyer would dislike the property, whereas the deaf buyer would like it. We recognize, however, that the situation may be different with familiar objects that elicit an affective reaction independent of their attributes (cf. Reisenzein, 1992). In this situation, the affective reaction may depend again on the focus of attention. If an object with conflicting attributes is appraised at the level of the attributes, it is likely to elicit mixed feelings. However, if the same object is appraised as a whole, it may elicit only one affective reaction. For example, even a loving spouse typically notices some undesirable attributes in his/her spouse. However, that does not imply that a spouse constantly elicits mixed feelings. The reason is probably that spouses do not constantly evaluate their partners at the level of their attributes. However, when certain situations make the undesirable attributes salient, the emotional response is likely to be one of mixed feelings because spouses are likely to recognize positive aspects along with the salient negative aspect. Future research needs to examine affective reactions to conflicting situations with different stimuli, different paradigms, and in ecologically valid situations. Practical Implications Our findings also have interesting implications for mood regulation (NolenHoeksema & Morrow, 1993), emotion regulation (Gross, 1999), and pain management (Eccleston & Crombez, 1999). Many affect-regulation theories consider distraction as an important regulation mechanism. That is, people can regulate affect by manipulating their attention. However, often the negative affect and its sources command attention, which Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 17 makes affect regulation difficult. Hence, it is important to determine which distraction strategies are successful. Intuitively, one might expect that a state of unpleasant-tension could be best undone by an opposing stimulus that is pleasant and calm. However, our work shows that pleasant and calm stimuli were less effective in reducing displeasure than pleasantarousing stimuli. This finding is consistent with the literature on distraction from pain, which shows that engaging and demanding distracters are more effective than pleasant distracters (Eccleston & Crombez, 1999). Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 18 References Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Cuthbert, B. N., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation I: Defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 276-298. Bradley, M. M., Codispoti, M., Sabatinelli, D., & Lang, P. J. (2001). Emotion and motivation II: Sex differences in picture processing. Emotion, 1(3), 300-319. Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542-575. Eccleston, C. & Crombez, G. (1999). Pain demands attention: A cognitive-affective model of the interruptive function of pain. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 356-366. Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion regulation: Past, present, future. Cognition & Emotion. Special Issue: Functional accounts of emotion, 13(5), 551-573. Kahneman, D. (1999). Objective happiness. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 3-25). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Kahneman, D., Diener, E., & Schwarz, N. (Eds.). (1999). Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage. Kappas, A. (2001). A metaphor is a metaphor is a metaphor: Exorcising the homunculus from appraisal theory. In. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion. Oxford University Press. Lang, P. J., Bradley, M. M., & Cuthbert, B. N. (1995). International affective picture system: Technical manual and affective ratings. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida. Lang, P. J., Greenwald, M. K., Bradley, M. M., & Hamm, A. O. (1993). Looking at pictures: Affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions. Psychophysiology, 30, 261273. Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 19 Lazarus, R. S. (2001). Relational meaning and discrete emotions. In. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion. Oxford University Press. MacLin, O. H., MacLin, M. K., & Malpass, R. S. (2001). Race, arousal, attention, exposure, and delay. Psychology, Public Policy, & Law, 7, 134-152. Mogg, K., McNamara, J., Powys, M., Rawlinson, H., Seiffer, A., & Bradley, B. P. (2000). Selective attention to threat: A test of two cognitive models of anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 14(3), 375-399. Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Morrow, J. (1993). Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition & Emotion, 7(6), 561-570. Ortony, A., Clore, G. L., & Collins, A. (1988). The cognitive structure of emotions. Cambridge: England: Cambridge University Press. Pratto, F. (1994). Consciousness and automatic evaluation. In Niedenthal, P. M., & Kitayama, S. (Eds.), The heart's eye (pp. 115-143). Academic Press: New York. Pratto, F., & John, O. P. (1991). Automatic vigilance: The attention-grabbing power of negative social information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(3), 380391. Reisenzein, R. (1992). A structuralist reconstruction of Wundt's three-dimensional theory of emotions. In H. Westmeyer (Ed.), The structuralist program in psychology: Foundations and applications (pp. 141-189). Toronto: Hogrefe. Reisenzein, R. (2001). Appraisal processes conceptualized from a schema-theoretic perspective: Contributions to a process analysis of emotions. In. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion. Oxford University Press. Reisenzein, R., & Spielhofer, C. (1994). Subjectively salient dimensions of emotional appraisal. Motivation and Emotion, 18, 31-77. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 20 Rozin, P. (1999). Preadaptation and the puzzles and properties of pleasure. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 109-133). New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296-320. Scherer, K. R. (1984). Emotion as a multicomponent process: A model and some cross-cultural data. In K. R. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), Review of Personality and Social Psychology (pp. 37-63). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Scherer, K. R. (2001). Appraisal considered as a process of multilevel sequential checking. In. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion. Oxford University Press. Schimmack, U. (2001). Pleasure, displeasure, and mixed feelings? Are semantic opposites mutually exclusive? Cognition and Emotion, 15, 81-97. Schimmack, U. (2002, February). Affective reactions to conflicting objects: The distributed attention theory of emotions. Paper presented at the third annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Savannah. Schimmack, U., Bockenholt, U., & Reisenzein, R. (in press). Response styles in affect ratings: Making a mountain out of a molehill. Journal of Personality Assessment. Schimmack, U., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2002). Life-satisfaction is a momentary judgment and a stable personality characteristic: The use of chronically accessible and stable sources. Journal of Personality, 70, 345-385. Schimmack, U., Oishi, S., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (2000). Facets of affective experiences: A new look at the relation between pleasant and unpleasant affect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 655-668. Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V. & Ahadi, S. (in press). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: Integrating process models of lifesatisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 21 Smith, C. A., & Kirby, L. D. (2000). Consequences require antecedents: Toward a process model of emotion elicitation. In J. P. Forgas (Ed.), Feeling and thinking (pp. 83106). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Smith, C. A. & Kirby, L. D. (2001). Toward delivering on the promise of appraisal theory. In. K. R. Scherer, A. Schorr, & T. Johnstone (Eds.), Appraisal processes in emotion. Oxford University Press. Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York: Springer. Wierzbicka, A. (1992). Talking about emotions: Semantics, culture, and cognition. Cognition and Emotion, 6, 285-319. Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations Figure 1 Pleasure in Response to Erotic and Non-Erotic Positive Pictures in the Context of Neutral, Moderately Negative, and Strong Negative Pictures Figure 2 Displeasure in Response to Erotic and Non-Erotic Positive Pictures in the Context of Neutral, Moderately Negative, and Strong Negative Pictures Figure 3 Combination Index for Four Types of Conflicting Picture-Pairs Figure 4 Mixed Feelings in Response to Four Types of Conflicting Picture-Pairs 22 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 5 Pleasure 4 3 2 1 0 neutral moderate negative erotic non-erotic strong negative 23 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations 5 Displeasure 4 3 2 1 0 neutral non-erotic moderate negative strong negative erotic 24 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations Combination Index 2.5 1.5 0.5 -0.5 -1.5 -2.5 non-erotic moderate negative erotic strong negative 25 Affective Reactions to Ambivalent Situations Mixed Feelings 1.5 1 0.5 0 non-erotic moderate negative erotic strong negative 26